To begin, an important caveat: I’m not a big reader of furry genre fiction.

I am, though, a furry and a keen reader, so I find myself attracted to furry writers and booksellers, furry books and reviews. When pressed, I say that I don’t read much furry fiction because I don’t think it’s going to be very good.

I recently decided it was time for a rethink. My interest has been piqued over the years by people writing about furry books, by furry writers in general, and by my exposure to a few furry short stories. I found the best of them to be well-constructed and enjoyable, if a bit disposable.

I’m also slightly fascinated by those people who write furry books for a living. Their job feels a bit claustrophobic to me, writing as they are to a small but engaged audience – like a tiny version of the sci-fi readership – a tough demographic.

Successful authors will win a dedicated following, but the bulk will struggle to find a critical mass of fans. If you enjoy writing, how do you decide whether to upload it for all-comers on SoFurry, or to publish it for sale?

I figured the best place to start would be to read the best furry fiction available. I asked around on Twitter and got a strong recommendation for Green Fairy, by Kyell Gold1. (Disclosure: I’ve met Kyell, and we get along well.)

It’s fair to say that Green Fairy is an ambitious work. It doesn’t tell a straightforward story and it doesn’t include explicit sex scenes, as with many of Gold’s other works. Green Fairy mixes accessible ideas with higher pretensions: in some ways it’s a teenage coming-out story, in others it’s about the value of art itself. It succeeds in its attempt to be a readable, enjoyable book; but it fails in its aspirations to literature.

Roughly, the book follows the story of Sol: a young gay wolf simultaneously trying to manage competing pressures from his internet boyfriend, his father, and school life. He’s a baseball player who has recently lost his starting place in the team, a move possibly precipitated by an embarrassing erection-in-the-shower incident. Sol has to contend with homophobic abuse and bullying in school, and pressure from his father at home.

In many ways, I’m a natural reader for Green Fairy. I’m furry, gay, and know my way around a sports field. Much of Sol’s experiences in Green Fairy are familiar to me, and Gold’s descriptions of school and sport life have a ring of truth.

That’s all good, but Gold runs into trouble with the structure of Green Fairy. Sol is reading a book for a school assignment called Confession, and soon enough the chapters of Green Fairy switch between Sol’s life and sections of Confession itself: a book-within-a-book. This is key to the novel, as aspects of Confession start to intrude on Sol’s day-to-day life.

Confession is introduced as a translation from a 1920s French novel. However it’s not at all convincing. Gold adopts a rather stiff style for the Confession sections, a style that makes me question the skills of his fictional translator. I think the best way to make this example is to compare the opening sentences of Green Fairy and Confession.

Green Fairy: “Sol was only reading a news story about a college student who’d killed himself, but the student had been gay, so when the young wolf’s fur prickled with the feeling of someone watching staring at him, he hid the story behind the picture of a car at some local auto dealer’s website.”

Confession: “Dear père, I know that this is not what you meant when you said you wanted all of Lutèce to speak my name.”

Green Fairy‘s opening sentence is terrific. We learn a lot about Sol – he’s self-conscious, probably gay, possibly considering suicide – and the sentence has a beautiful rhythm as Sol’s attention shifts from himself to his worry about how he is seen from the outside. We know that Sol is trying to hide aspects of himself from the world. (There is also a hint of the literary convention that any book that opens with suicide must close with suicide: Green Fairy doesn’t quite go that far, but suicide is a key plot point towards the story’s conclusion.)

Confession‘s opening sentence has me contemplating, if not my will to go on living, at least the will to go on reading. It’s stilted to the point of being hard to follow. The phrase “not what you meant when you said you wanted” is a discordant succession of clanging syllables. And why oh why would our fictional translator not translate “père” to “father”?

Gold’s intent is pretty clear. He is trying to write Confession in a different style to that of Green Fairy. It’s a good idea, but his attempts to make Confession sound (1) French; and (2) old; are played far too broadly. The remainder of the opening paragraph of Confession manages to drop terms like “scurrilous” and “bourgeoisie”, as well as wheeling out such boilerplate Frenchified cheese as a reference to beheaded monarchy. I’m happy to say, at least, that Confession gets better as it goes.

The book-within-a-book structure is a tough trick to pull off. Both books need to stand alone to be believable, yet they must inter-relate in a way that makes sense. Even the mighty Vladimir Nabokov was unable to completely succeed: his 1962 novel, Pale Fire, has a 999-line poem at its heart, supposedly composed by a peer of Robert Frost. And Nabokov, one of the great novelists, is not a Frost-quality poet. Assertions of the genius of Pale Fire‘s poet and the quality of his 999-line poem (which are integral to the book’s story) just don’t ring true.

Where greats like Nabokov stumble, others faceplant. The Art of Fielding by Chad Harbach is a 2001 book with a lot of elements in common with Green Fairy. They both have a central gay romance, the plot is driven by school/college hierarchies and the mental health of the main character, and both books are about baseball. The hero of The Art of Fielding owns a supposedly legendary book about the psychology of baseball – also called The Art of Fielding – which he slavishly follows and regularly references. The problem is that The Art of Fielding (the book within the novel) is mind-boggling faux-new-age poppycock, ludicrous if considered as a stand-alone entity, let alone as a work of great wisdom and inspiration.

Green Fairy fails because its execution doesn’t live up to its aspiration. Gold laudably sets himself a tough task, but fails to pull it off. C’est la vie.

Green Fairy is, of course, a furry novel. It is set, more or less, in today’s world but with anthropomorphic animals instead of humans. This is both the novel’s biggest strength and greatest weakness.

In his review of Green Fairy for Flayrah, Fred Patten praises Gold for his “signature worldbuilding”. His mixture of anthropomorphics with the real world is genuinely vibrant, and species differences have a real effect on the lives of the characters. Gold makes scent important to his wolf characters, otters live in and around water, and so forth.

Reading about animal-people is very pleasant, acting as a kind of wish-fulfilment for the furry reader. It helps make the book emotionally affecting and generally more engaging. Unfortunately, and perhaps inevitably, Gold’s furry universe doesn’t hold up.

Gold’s furry characters live in our world. Green Fairy takes place partly in 1920s France – replete with Parisian landmarks like Les Halles and the Moulin Rouge – and partly in present-day America, with mundane schools, sporting scholarship programmes, cars, geopolitics, technology, and so forth.

The facade of this world crumbles when it becomes clear that the furry aspects of Gold’s universe are in fundamental conflict with his real world setting.

It is probably fair to say that this is an unavoidable problem. Writers can create from-scratch universes where only furries exist, or they can create slightly different versions of our world where furries co-exist with humans. But stories where furries exist in today’s world in place of humans, like Green Fairy, run into problems. It is, I suspect, a limitation of the genre.

Gold is smart enough to avoid obvious instances of logical dissonance, stopping short each time he threatens to create a contradiction. Also to his credit, he doesn’t try to resolve potential contradictions by tediously attempting to over-explain things. He is walking a fine line. On one hand, he provides enough information for the story to be grounded in reality; on the other, he holds back detail when logical contradictions loom on the horizon.

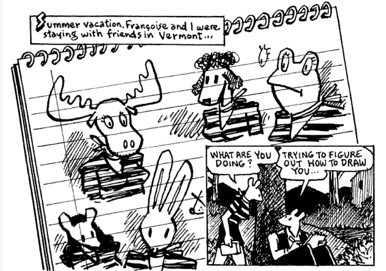

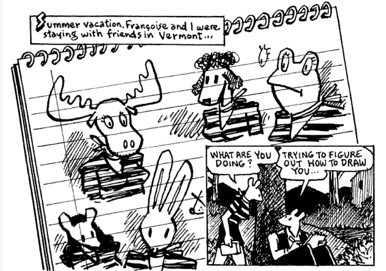

Art Spiegelman walks a similarly fine line, and similarly stumbles, in Maus, his Pulitzer Prize winning graphic novel. Maus is a true story, following Spiegelman’s father during the Holocaust, with the Jews drawn as mice and the Nazis as cats. It’s a simple enough metaphor, but one that fails once characters from other races get involved. Spiegelman’s solution is to draw two pages – two boring, irrelevant pages – showing himself trying to decide how to draw his French wife. Spiegelman tries to make these two pages relevant to Maus by dropping a couple of vaguely racist comments – his wife is a ‘frog’ and he calls himself prejudiced against Jewish women – but this feels less like a comment on the ubiquity of inherent racism, more like an attempt to distract from his admission that his metaphor has failed.

The furries of Green Fairy aren’t used as a blunt metaphor like the mice and cats of Maus, but Gold has the same challenges of retaining the integrity of his universe. Gold, thankfully, doesn’t go all intrusive-author on us like Spiegelman, but the logical problems are still there.

For starters, there are biological problems. The students of Green Fairy‘s Richfield High, heterosexual and homosexual, very obviously regard one another as potential romantic partners. There is no suggestion that there is any problem with mixed-species coupling, and indeed it’s a running gag that Sol’s platonic female friend (Meg) wants to give the appearance that their relationship is a sexual one.

The problem comes about when you look at the parents of each of the students: they are all single-species. Meg the otter has two otter parents, Sol the wolf has wolf parents, and so forth. The operation and physical reality of each household is (in part) defined by the species of the family unit, such as the otters living around water, and the characters tend to refer to other families in this way.

It’s easy to see how Gold is backed into a corner: on one hand he wants a rich, multi-species furry world, and on the other he wants each household to be defined by a single family species. But these two things are incompatible, barring perhaps some unmentioned but recently-repealed species apartheid law.

Similarly, Gold runs into problems when he explores the difference between carnivores, omnivores, and herbivores – one of the sources of conflict that drives Green Fairy‘s plot. Some of our furries are eating meat, and Gold makes a passing reference to non-anthro animals being used for food. This solves one problem but introduces a whole host of others: how can Gold’s animal-person society consider this ethical (or at least unworthy of comment when the ethics of vegetarianism is raised)? Who is farming these animals – are anthro cows raising and slaughtering non-anthro cows? And surely our animal-people would feel some kinship with their non-anthro counterparts, especially the more intelligent species, like wolves?

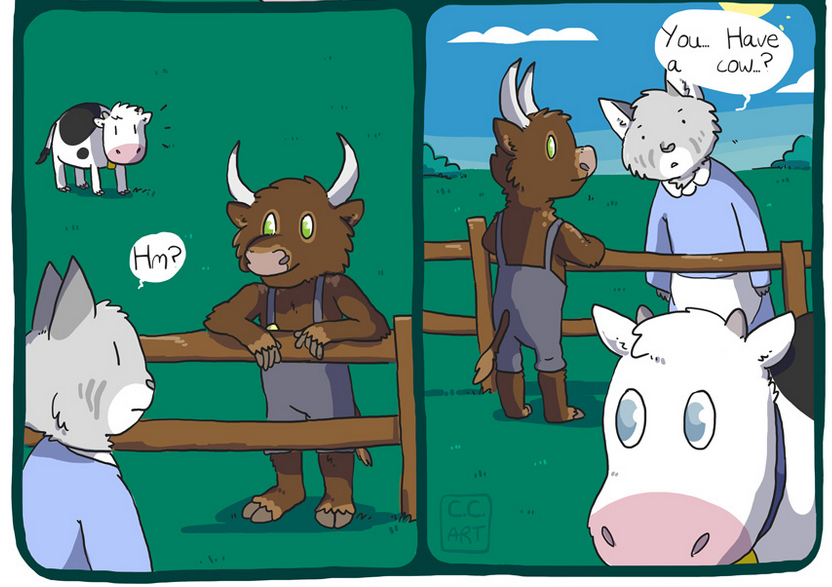

From Claire C’s comic Harvest

Gold doesn’t answer these questions, and nor should he. It would be boring, and undoubtedly lead to deeper logical problems, short of Green Fairy taking an unexpected twist into some Gulliver’s Travels-esque dystopia. But while his decision to elide this difficulty is correct, the difficulty still exists.

Gold’s characters have mundane problems: a budding romance, or bullying, or a place in a sports team. These are modest and subtle drivers. Gold’s plot relies on conflict caused by such social pressures, for example Sol’s desire to hide his homosexuality, or his efforts to win back his spot on the baseball team. But it’s difficult to care for the characters in thrall to the pressures of Green Fairy‘s universe, because Green Fairy‘s universe doesn’t hold up to scrutiny.

Interestingly, Gold makes intimations towards the natural challenges of his multi-species and multi-cultural society. Sol’s baseball rival is a young, talented coyote, who is driven to prove himself to the baseball team’s alpha wolf clique. Sol’s failure to keep his spot is especially embarrassing because his rival is considered ‘lesser’ in the eyes of his father, who comes across as a little bigoted (speciesist?).

In conversation with another parent, Sol’s father explains why Sol is playing backup:

“One of those ‘yotes from the trailer park,” Sol’s father said finally. “Tough, scrappy…”

[…]

The words don’t seem to register with the other wolf. “Y’know, once those trailer kids set their mind on somethin’…” He shook his head. “Don’t get between one of them and a steak, know what I’m sayin’?”

This is the language of casual racism, and it’s notable that it’s spoken by the older generation. It’s easy to replace “‘yote” with a racial minority, consider the apparent economic disadvantage of the group, and see that Gold is weaving elements from our own human social experience into his furry world. It is obvious to the reader that Sol’s father and his friend are wrong to mark an entire species/racial group with broad generalizations, in this case roughly “poor” and “recalcitrant”. Sol disagrees without saying so, and the reader empathizes with the conflict between his desires to keep mum and to speak up.

I bring up this example because it illustrates two things. Firstly, it demonstrates Gold’s quality as a writer, using a few efficient lines to get across a complex idea. Secondly, his intimations of racism are edging into dangerous territory. If species differences in Green Fairy are akin to racial differences, Gold appears to be drawing parallels between a single species (coyotes) and an American racial minority.

Other species in Green Fairy are similarly marked. There are a couple of Siberian foxes in the book, both of which are of Russian origin (one speaks in delightfully broken English). Here, again, species seems to relate directly to race.

This is dangerous because it appears that some species stand for single racial minorities, but that the other species collectively stand in for a racial majority – ostensibly white people, displaying as they do the trappings of suburban affluence. The idea that individual diversity occurs within a white population but that other racial groups can be collected as a discrete ‘other’ is wildly racist. Gold, of course, doesn’t say anything of the sort. But, to me at least, this is an unintended problem with the foundation of Green Fairy‘s world.

To be clear – there are no elements of Green Fairy that could be construed as even vaguely racist. This is simply an example of the problems Gold introduces by taking our world, and replacing humans with anthro characters. The drama and plot of Green Fairy are driven by familiar social pressures, and racial tension is a part of that. The problem isn’t with Gold’s treatment of race, it’s with the premise of his universe. Art Spiegelman has exactly the same problem with Maus.

The most obvious problem with Green Fairy, at least the paperback version, has nothing to do with Kyell Gold. It’s the illustrations. There are a dozen or so drawings by Rukis in the book, showing certain key scenes.

Rukis is a fine illustrator. The front cover of Green Fairy in particular is excellent. Less successful are the scenes captured by her art inside the book, mostly of action scenes, from a dance inside the Moulin Rouge through to an attempted rape. These drawings are DOA. Compared with Gold’s engaging and evocative prose, Rukis’s art is lifeless and flat. She would have been better served, perhaps, by providing character portraits of Gold’s main players.

It makes me wonder what on earth illustrations are doing in Green Fairy in the first place. The last time I read a book with pictures, I was 9 years old, and the story was about a kangaroo who went on adventures. Maybe this is a furry genre convention? Do furry books usually include picture?

Despite Green Fairy‘s problems, Gold’s writing skill stands out. The structure of Green Fairy would be challenging for any writer, and on the whole he executes well. Even the Confession sections markedly improve as the book goes on. It makes me wonder if Gold wasn’t learning as he wrote, starting on unfamiliar ground but finding his feet as he progressed through the story. If so, it’s testament to his skills as a writer – he starts formal and stiff, but ends with a bit of rhythm and flourish. I suspect that Gold should have rewritten the opening sections of Confession once he had found his voice, much like a real translator would do.

It’s not just the structure of Green Fairy which is complex, but Gold’s themes. His story is driven by conflicting social pressures, as would be familiar to any high school student, amplified by Sol’s unusual combination of competing hopes and dreams. Gold writes with clarity, and the plot has great energy despite Sol’s introspective nature.

I was particularly impressed by Gold’s development of Sol’s antagonists. Sol feels bullied at the beginning of the book, yet Gold avoids creating cardboard cut-out enemies. The motivations of Sol’s antagonists become apparent as the plot moves forward, and we can sympathize with them even while they engage Sol in emotional, physical, or sexual conflict. We don’t spend any time with these other characters directly, so we never get detailed insight into their thoughts. Instead, Gold humanizes them with context, providing hints that Sol notices but can’t dispassionately process, so that the reader has information that Sol does not. This is skilful writing by any measure.

Gold manages to invoke the emotional instability and general drama of being a teenager, both with Sol and with his fellow students. To be young is to be self-centred, and Gold understands that the characters will treat any event as if it is somehow personal. His single major female character, Meg, is Sol’s age but more emotionally mature, able to more effectively empathize with others but still prone to her own bouts of self-focussed drama. Gold’s older characters are, on the whole, a lot more moderate in their emotional expression.

Gold uses the natural teenage tendency to be self-conscious and self-critical to push his characters around. If anything, he holds back a touch, as if he can’t quite drive his characters too close to the edge – Sol is never really humiliated or embarrassed (although of course Sol doesn’t really see it that way). Yet Gold knows that we all remember what it was like to be in high school, and his emotional manipulation of the reader is deft, especially in the opening chapters. I found it very easy to empathize with Sol.

Even better is Gold’s writing on sport. Sport is a notoriously difficult topic for a writer, particularly action sequences. Sports fiction writing must balance the need for basic explanation, context, and the inevitable sports jargon, all while maintaining continuity of style. Too often sports writing devolves into a dry listing of events, all action and no thought. Many writers choose to avoid action scenes altogether, by narrating the action in hindsight, as remembered rather than as experienced.

Throughout Green Fairy (excluding the Confession sections), Gold retains an urgent tense, and we get to experience events as Sol experiences them. He retains this urgency through the short baseball sections, and it’s clear that Gold has a strong feel for the mechanics and psychology of the sport. He understands that sport is experienced twice: once in reality and again in hindsight. In reality things happen in a fraction of a second, where actions and decisions are unconscious. It’s in hindsight that post hoc reasoning gets applied, and over time the logic of hindsight replaces the instinct of action – the rationalization becomes the reality. And so when Sol gets it wrong on the baseball field, an unlucky bounce transmogrifies into an error that demonstrates Sol’s emotional weakness.

Gold also understands what it means to be an expert on the sporting field. Even in a long game like baseball, a state of ‘flow’ can occur, where actions and decisions happen automatically and time melts away. Sol is an experienced baseballer and manages to achieve this state from time to time, and accordingly Gold has these sections over in a flash. When Sol is struggling, Gold – excruciatingly – takes his time.

This is another obvious point of comparison to Chad Harbach’s Art of Fielding, where baseball is also a central focus of the story. Gold’s treatment of baseball in Green Fairy is comfortably more assured than Harbach’s, as is his treatment of social pressures in a school environment, and of hidden homosexuality, and – for that matter – his humour. Gold’s writing stands above Harbach’s… and to put this in context, Harbach received a $650,000 advance for Art Of Fielding, and an HBO series is planned.

Green Fairy‘s main limitation, in my opinion, is Gold’s decision to make it a furry book. The presence of furry characters, in place of humans, causes Gold no end of predictable problems, and this comes at the detriment of the book as a whole. And while, as a furry, I (subjectively) liked reading about Gold’s animal-people and found it easy to engage with them, a non-furry Green Fairy would be objectively better.

Gold is a terrific writer. He is no great stylist, but he is clear, efficient, and subtle in his plotting and character manipulation. His attempt to balance several writing styles in Green Fairy, although not entirely successful, demonstrates his ambition to create something special. Furry readers are lucky to have him, and it’s no surprise that he has a dedicated following.

Green Fairy is good… for a furry book. I have no doubt that my recommendations were fair, and that it stands out as a high point of the genre. But it doesn’t compare favourably to non-furry books, and unfortunately this seems to be due to the furry component itself.

Is the furry genre self-limiting? Goodness knows there is a lot of writing out there in furry, which means a lot of hay and very few needles. And still there may not yet be a great furry book. Any suggestions?

_______

1.There was one other popular recommendation: God of Clay, by Ryan Campbell. Unfortunately I couldn’t find a way to buy a copy without incurring an enormous shipping charge. I’ll buy God of Clay next time I’m at an American convention.

Matt Healey tweets at @jmhorse.