I’ve been assembling an ur-team of Avengers for my book On the Origin of Superheroes, and my first-ever superhero award goes to the Golem. He’s super-strong, impervious to pain, and, when made from clay, can even shapeshift a bit. On the downside, he’s dumb in both senses and so requires close supervision. Sorcerers and programmers beware.

“There is nothing more uncanny than something that is almost human,” says Margaret Atwood. “All our stories about robotics are stories like that. It’s what we have always worried about. It’s the sorcerer’s apprentice story: He learns how to do the charm; he doesn’t know how to turn it off. It’s the Golem story: You make the Golem, you activate it, it’s supposed to do your work for you, and then it runs amok.”

Atwood’s Oryx and Crake trilogy features a genetically engineered species of designer humans, but they’re too mellow to cause the survivors of her apocalypse much trouble. When it comes to magic brooms and water buckets running amok, I picture Mickey Mouse, but Goethe published his poem “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” while Napoleon was still waging France’s Revolutionary Wars.

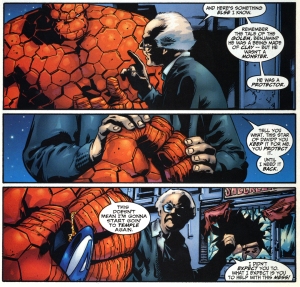

Apparently Goethe cribbed the tale from Lucian’s Philopseudes, c. 150 CE, though the word “golem” is even older. It means “shapeless mass” in Hebrew, which is the description of Ben Grimm that Stan Lee typed up for Jack Kirby in 1960: “He’s sort of shapeless—he’s become a THING.” Kirby drew a giant bumpy rock monster that turned orange at the printer’s. I don’t know if either had the Golem in mind, but Fantastic Four writer Karl Kesel did when he decided forty years later that Ben’s full name was Benjamin Jacob Grimm.

Benjamin grew up going to synagogue as a kid and could still recite Torah passages from memory, so he probably knows that “golem” first appears in Psalms 139:16 (“my substance, yet being unperfect”) when David praises God for creating him. The Talmud (c. 200 CE) uses the term to describe Adam’s creation too: “In the first hour, his dust was gathered; in the second, it was kneaded into a shapeless mass.” But jump forward another couple hundred years, and a passage mentions the first living golem: “Rabbah created a man, and sent him to Rabbi Zera. Rabbi Zera spoke to him, but received no answer. Thereupon he said unto him: ‘Thou art a creature of the magicians. Return to thy dust.’”

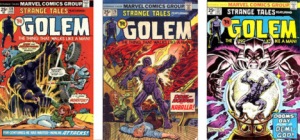

Apparently they weren’t all that hard to manufacture. All Pygmalion had to do was pray to Venus to bring his ivory statue Galatea to life. Daedalus soldered his golem Talos from bronze. If you’re up on your Kabbalistic techniques, Sefer Yetzirah (The Book of Formation) gives a how-to, but Aryeh Kaplan warns apprentices not to attempt it alone. Virgin dirt is also key. Marvel was still printing on pulp paper in 1974, which is why their Strange Tales Golem only ran three issues. Writer Len Wein gave the legend his best superheroic spin:

In centuries agon, they had called him a myth, a creature formed of stone and clay and the blood of a people’s oppression—a moving monolith who rose before the yoke of tyranny—shattered it in his monumental fists—then vanished into the sands of time—there to be almost forgotten—until today! Now once more he rises—summoned from his eons-long sleep to protect those he loves.

Marvel tries not to take sides in the Palestine-Israeli conflict, declaring it

a war of territory, of ideologies—fought with great fervor but with little gain—fought with loaned weaponry wielded by men—men charged with love of country and the courage of their convictions, but men nonetheless—aye, as in all wars before this, fought by men—imperfect, all-too-human men.

But those the Golem loves are the family of Jewish archeologists who dig him up, while General Omar leads an army of marauding rapists who pillage the archeological camp and machinegun the grandfather. Uncle Abraham’s dying tear reanimates the creature. “Eyes of a camel!” shouts one of the keffiyeh-wearing soldiers. “The statue—it lives!”

Michael Chabon’s golem surfaces for far less dramatic adventures. His amazing Kavalier and Clay find its coffin filled

to a depth of about seven inches, with a fine powder, pigeon-gray and opalescent, that Joe recognized at once from boyhood excursions as the silty bed of the Moldau . . . . The speculations of those who feared that the Golem, removed from the shores of the river that mothered it, might degrade had been proved correct.

My wife and I sat along the banks of the Moldau (AKA Vltava) sipping Budvar in a Prague café in 1996. The ground was too paved to be termed virginal, but the city has a legion of statues and tourist shop figurines already prepped for animation. Prague is to Golem as Metropolis is to Superman. The tales proliferated there like magic brooms in the 1800s. One named Josef protected Jews from a supervillainous Emperor with the additional superpower of invisibility—so basically half of the Fantastic Four. Benjamin Kuras, author of As Golems Go, explains why Golem still adventures in the Czech Republic:

After living through the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Nazism and decades of communism, the Czechs are drawn to a character with supernatural powers that will help liberate them from oppression.

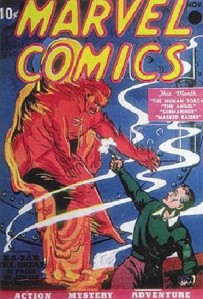

The Golem is also the original “robot,” a Czech word for “laborer” or “slave.” Karel ?apek’s play R.U.R. (AKA “Rossum’s Universal Robots”) unleashed them on the world, resulting in the extinction of the human race in 1920. Despite the nuts-and-bolts contraptions in promo shots, Kapek’s robots are the flesh-and-blood variety, more like clones or Philip Dick’s sheep-dreaming replicants. Carl Burgos had the same idea when he drew the Human Torch for Marvel Comics No. 1 in 1939. The flames were one of those unintended “run amok” side effects, but rather than burning Brooklyn to the ground, the almost human Torch gets his superpower under control (bringing our Fantastic Four tally to 75%) and vows to help humanity even though humanity tried to seal him in a steel and concrete cage.

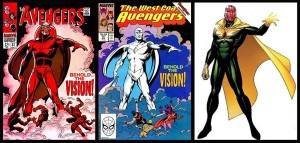

The Human Torch fizzled in the forties and wandered out to the desert to die—the same fate Wein copied for his Golem. The evil robot Ultron rebuilt the Torch’s burnt-out corpse in 1968, and he was reborn as my favorite childhood superhero, the Vision. But then the original Torch erupted from a secret grave in the 80s, so the Vision was never really the Torch but a copy soldered from spare parts. Only, no wait, that’s not it either, because next it turns out the Vision and the Torch are in fact the same synthoid split in two when a time-traveling supervillain manipulated the timeline. Except then the Vision half was ripped apart by She-Hulk, and his identity may or may not inhabit the sentient armor of the time-traveler’s teen-age self, while his soul returned in a team of Dead Avengers before Tony Stark reassembled his body. And don’t even get me started whether that body is the kind with buzzing wires and clanking pistons or the kind with synthetic organs that gurgle and fart.

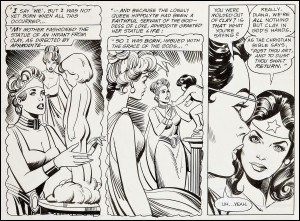

Human animation is simpler. My wife returned from Prague pregnant with our daughter. King David praises God for “cover[ing] me in my mother’s womb,” but we followed a very different nuts and bolts process. Though nothing like the Thing, my daughter has been running amok for eighteen years now. She looks a lot more like the clay statue Hippolyte sculpted and, with the help of her gods William Marston and Harry G. Peter, brought to life in 1941—making Wonder Woman the original comic book Golem. Sadly, she’s not available for my team of First Avengers.