In his review of Monster, Noah advises us that he would “rather pursue the trashier Gantz, which manages to be a lot more thoughtful and truthful about morality by the simple expedient of not idolizing its central characters.” Having read a few more volumes of the series, I would suggest that Noah mistakes base instincts, unfiltered onanism and self-indulgent stupidity for those more virtuous attributes.

That’s Suat, suggesting, in his sweetly understated way that I don’t know what I’m talking about.

So after reading the first 20 or so volumes of Hiroya Oku’s Gantz, have I seen the error of my ways? Well, not exactly.

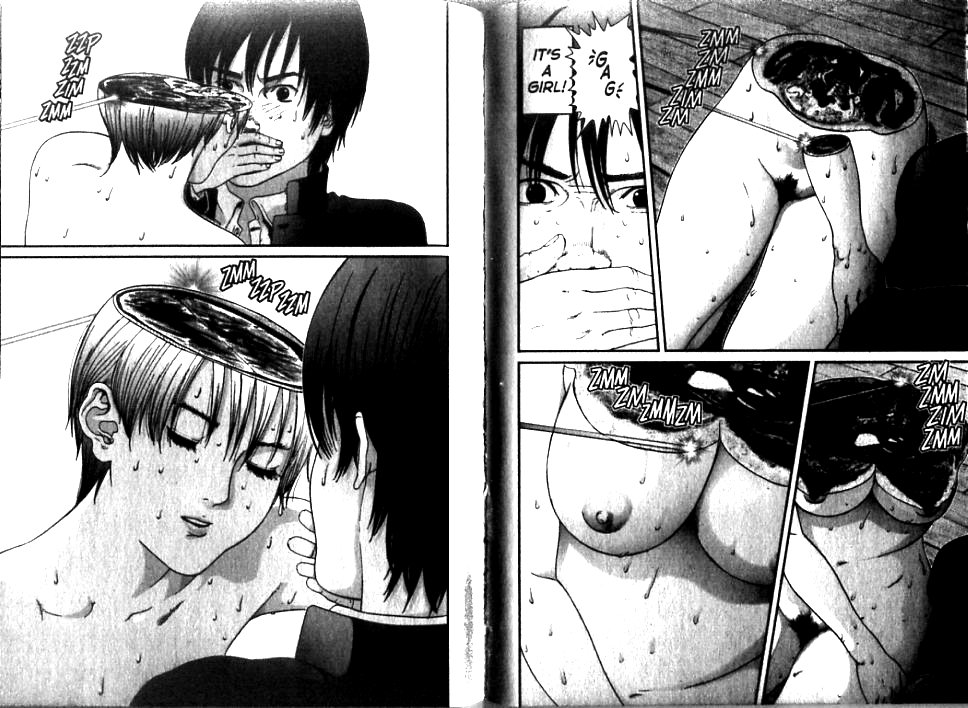

Suat argues in his review that Gantz is bargain-basement wank material for clueless adolescents, composed of little more than pallid violence, pallid titillation, and pallid nihilism.

It would be easy to imagine this manga being put together by a bunch of sexually deprived nerds huddled around a computer screen but, no, I’m going to be kind here and just call them a group of over-sexed wankers. Gantz is clearly aimed at young males with a history of gaming, buying gravure idol magazines and indulging in H games. Nothing particularly unusual or pathetic here. Everyone can do with a bit of interactive porn now and then, but let’s not mistake this for great entertainment much less great art.

I wouldn’t call Gantz great art necessarily — I think I’m somewhat less interested in that kind of ranking than Suat is in any case. But at least in its early volumes, Gants does have a sense of pacing and atmosphere which I found compelling.

Tucker Stone gets at the book’s appeal a bit when he notes that:

Gantz is the true heir to Peter Parker, and… this–sleazy violence in Matrix jumpsuits–is where you turn if you’re looking for a contemporary Spider-Man comic. It’s 2010, and responsibility is an advertising tagline. Nowadays, a fresh-from-puberty kid with great power would use it to kill anybody that messed with him (every volume so far) and fuck Angelina Jolie (which he did in volume 8.)

For Tucker, this is, like Spider-Man and super-hero comics in general, a power fantasy — but a power fantasy pushed somewhere different than you usually find in super-hero comics. Tucker argues that the difference is one of exploitation: Gantz has more explicit sex and more explicit violence than Spider-Man does. This is true — but I don’t know that that’s especially interesting in itself. After all, most super-hero comics these days are dripping with explicit sex, explicit violence, and various other fluids. Fine-tuning the power fantasy for older, more decadent readers is a tried and true strategy at this point.

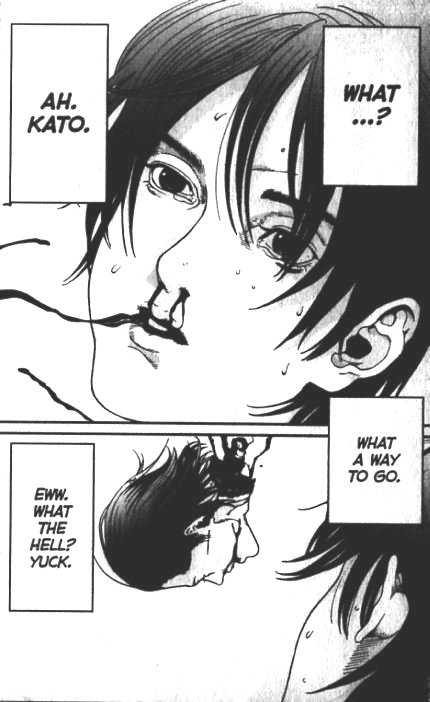

What’s different about Gantz is not that the power fantasy is nastier, but that it exists in a kind of blank fugue. You see this from the manga’s first scene — which is also probably the best sequence in the series. High-school student Kei, the book’s hero, is standing on a train platform reading a girly mag and sneering internally at his fellow commuters. Suddenly he notices that a childhood friend, the extremely tall Masuru, is standing next to him. Kei doesn’t speak to his former friend…and then a bum falls off the platform and onto the tracks. Masuru leaps down to help him, but can’t lift him by himself. He looks up, notices Kei, and calls him by name. Kei, who doesn’t like Masuru, finds himself crawling down to aid him almost despite himself — because he likes Masuru more than he thinks? Because he feels like the other commuters expect it of him? It’s entirely unclear even to him — and then the train comes and he and Masuru are hit and die. And then they wake up in an apartment with a bunch of random other people and a dog sitting around a black sphere.

The appeal of the opening is that the sci-fi elements — the transportation after death, the mysterious black sphere — are exactly as inexplicable as the inside of Kei’s own skull. Kei really doesn’t understand himself anymore than he understands how he ended up in that room. He’s dislocated both internally and externally. Peter Parker’s life was transformed when he was bitten by that spider — but Kei? Who was he before he died? Where was he going? Who was he connected to? Nothing, nowhere, no one. This is adolescence as a transition from emptiness to emptiness, growing out of the aphasia of childhood into the aphasia of adulthood.

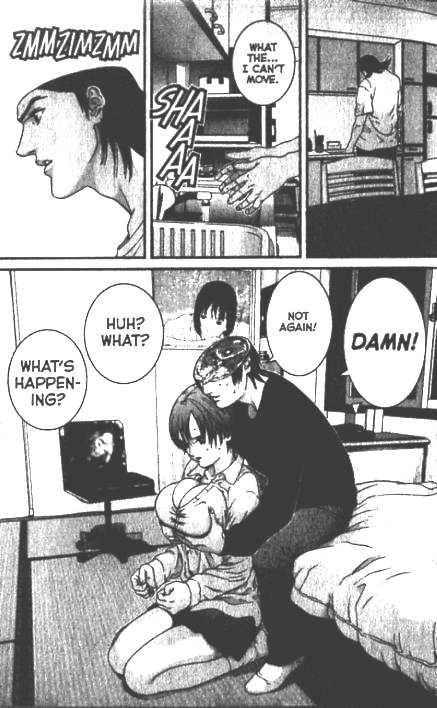

The series is unsettling, then, not because it’s especially brutal or sexually explicit, but because the brutality and exploitation take place in a kind of contextless void. For example, Kei, Matsuro, and the others gathered together by the sphere are all issued futuristic guns and ordered to go out and shoot various aliens. But the guns work on a delay; you pull the trigger and nothing happens for a few seconds, and then (sometimes) your target blows up. The violence here is just standard movie violence…but the time lapse is weird. It gives the battles a slowed-down, dreamlike feel, like the rules of physics have been changed and the characters are sitting staring at their navels as they drift off into space.

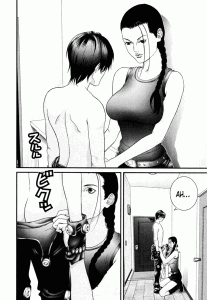

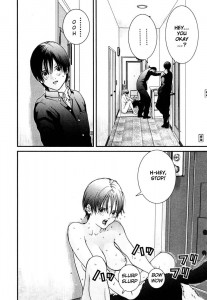

Kei’s sexual relationships work in a similarly disjointed way. Soon after he finds himself in the room with the sphere a naked girl appears literally out of thin air and falls into his lap; soon thereafter a dog licks her pussy; then sometime later she moves in with Kei and let him feel up her tits for reasons which are really unclear; somewhere in there he falls in love with her; she announces that she loves Matsuro; then at one point the two of them are walking down the street and they run into her exact double. Then later he asks a girl who looks like Angelina Jolie to have sex with him and she does.

Reading the first volumes maybe makes this a little more coherent, but not much. Emotional declarations and sex acts wander out of the blue and then wander back into it, like someone forgot to write random bits of the narrative and then was too lazy to go back and fix it. Oku’s insistent breast fetish becomes, in this context, just another way in which sex is severed from actual interaction — the gratuitous T&A pin ups sprinkled liberally throughout aren’t any more of a non sequitor than most of the events of the story itself. The overall effect is of a pulpier, clumsier Philip K. Dick or Murakami — and the pulp and the clumsiness make it in some ways more odd, not less.

Gantz doesn’t just feel like careless writing, but like a view of reality as carelessly written, in which people’s motivations and even their selves are incoherent. The way the sphere reconstructs the characters — building them up plane by plane so you can see their innards forming as they corporate — is a metaphor for how the book treats people in general — as weird shells built from blood out of nothing. The computer enhanced art only adds to the effect; the characters look too smooth, uncannily isolated from their backgrounds and each other, like they all exist completely independently, never touching either each other or their world.

If Gantz had ended after a couple of arcs — even (especially?) if it had just been cancelled in the middle of a storyline — it would be perfect in its disassociative imperfection. Alas, the remorseless grinding of the plot turns the protagonist from a confused and ineffectual cipher into a standard issue hero, blasting the bad guys, wowing the girls, and generally behaving like Spider-Man with a little more sex and violence. He gets a boring girlfriend who loves him, forms emotional connections, learns the virtues of self-sacrifice and leadership, and generally adopts a persona which is hollow in a much more predictable way. There is a certain poetic logic to having Kei mature from a vacuous nobody into an anonymous trope — but poetic or not, once the anonymous trope is firmly established (certainly by volume 9) there ceases to be much reason to continue to read.