Who is Hinako Sugiura?

Red Flowers. Sayako Kikuchi is lying in the shade of her tea shop. It is a warm summer day and far too hot to count the meager takings from the morning. There is the sound of cicadas in the background and we gaze up at this incessant activity with the girl. The tree before us is as firm and immovable as nature itself. The tea shop is cradled in its grasp, nestling in a womb-like clearing with tendrils and fruit running through its thatched roof.

This is a slightly edited and translated version of a piece on the great mangaka Yoshiharu Tsuge that I wrote for the Danish comics magazine Strip! and my website Rackham back in 2004. Considering his importance to Japanese comics, Tsuge remains sadly underrepresented in translation. Plus his name has come up in discussions here at HU several times, so I figured an introduction to his work would be an interesting addition to the mix here.

A boy emerges from the sea in the shadow of a C-47. He presses his right arm against his side where a deadly jellyfish has torn apart one of his veins. Whenever he releases the pressure, blood trickles to the cold ground, which he treads like a sleepwalker, searching for a doctor to help him. He passes a forest of shirts, is trampled by the silhouettes of a marching band, wanders along railway tracks bordered by empty signs. A rusty locomotive runs backward, steered by a boy wearing a cat’s mask. The protagonist hears the faint tingle of a chime in the wind, reminding him of summer. With an old lady who may be his mother, he eats phallic sticks of kintaro candy topped by small, disgruntled faces.

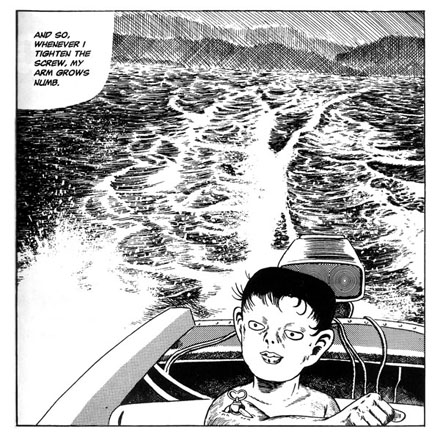

In a bombed-out bunker, he finds a female gynecologist dressed in a kimono and sporting a head mirror. She speaks in white as empty as the signs along the tracks and they play doctor against the backdrop of a Midway-like naval battle. A wrench, seen earlier in the hands of a suit who “almost knew what he meant”, suddenly reappears in the hands of the woman who uses it to fit his torn vein with a safety valve. Thus saved, he sails away in a motorboat with the parting words “And so, whenever I tighten the screw, my arm grows numb.”

This happens in Yoshiharu Tsuge’s most famous manga, the 22-page ”Nejishiki” (”Screw-Style”) from 1968. Like most of his comics, it was published in the legendary alternative comics magazine Garo. It is regarded as a central work in Japanese comics history and its creator has gone from cult-figure to eccentric celebrity in Japan. Born in 1937, he retired from cartooning in 1987, leaving behind a modest but highly significant body of work: around 150 short stories produced over three decades or so.

These are comics of such strange originality that he is often given the sobriquet “ishoku” (‘unique’); it has contributed crucially to the understanding in Japan of comics as a personal and artistic means of expression. Only a few of his comics have been translated into Western languages, but the ones available still enable us to assess the contours of an oeuvre that one might imprecisely but poignantly compare to that of Robert Crumb in America.

“Screw-Style” reportedly records a nightmare Tsuge had one day while sleeping on his tenement rooftop. Characteristically for his generation of cartoonists, perhaps most notably his one-time teacher Shigeru Mizuki (b. 1922), he integrates cartoon characters, whose appearance often changes from panel to panel, into backgrounds that vary from the loosely defined to the carefully rendered, often photo-referenced. The story is a surreal tour de force, strong in its critique of civilization and deeply pessimistic, with the central metaphor being a open wound exposed to a denaturalized, filthy industrial environment darkened by ash clouds and haunted by the shadow of war. It exemplifies Tsuge’s preoccupation with the pollution of the soul, shown through bodily metaphor: the protagonist’s only salvation lies in fusion with a metallic object—the safety valve that numbs his arm.

Making his debut as a cartoonist in 1954, Tsuge spent the next couple of decades producing genre comics for the large rental comics market, which in the postwar decades functioned as a different and very substantial alternative to the Tokyo-based mainstream publishers who would eventually eliminate it and evolve into the manga industry we know today. From the beginning, his comics operated within the more realistic tradition nurtured in the rental market. These comics were dubbed gekiga by Yoshihiru Tatsumi (b. 1935), which translates roughly into ‘dramatic pictures’, marking a contrast with the ‘whimsical pictures’ of manga as published by the commercial industry and shaped significantly by its great creative dynamo, the “God of Manga” Osamu Tezuka (1926-1989).

“Screw-Style” however marked a shift towards the allegorical and the surreal. This has led to a frequent distinction between his “surreal” and “realistic” modes, both of which he continued practicing. But this seems an artificial categorization: his mature (1960s onward) work invariably hews closely to lived life, but simultaneously imbues it with allegory or poetry. His unique blend of these different levels of representation is central to his fame as the originator of so-called watakushi manga, or ”I-comics”—the manga version of literature’s shishôsetsu, the ’I-novel’. It is related to what we understand as ’autobiography’, but considerably broader in scope.

In the sense that it derives quite significantly from its author’s internal life to create a deeply-felt critique of his Japan, ”Screw-Style” is bona fide watakushi manga. In fact, Tsuge’s life and work generally seem so interconnected that his comics, as well as his illustrated travel diaries and other published writings, provide an access point for the public to a more or less consciously constructed mythological narrative of his life. Its foundation is his Tokyo childhood during the war and its aftermath, and in contrast to the post-war optimism of much of his generation, engendered as it was by the country’s reconstruction and modernization, he is strongly pessimistic, at times borderline nihilistic.

In comics one might compare his contemporary Keiji Nakazawa (b. 1939), who as a child experienced firsthand the bombing of Hiroshima and its consequences and told his story in his masterpiece Hadashi no Gen (Barefoot Gen; original serialization 1973-1974—later continued). Though strongly indignant, Gen is a deeply humanistic work. Tsuge, on the other hand, eschews this optimisim and instead charts the equally pervasive meaninglessness and alienation of post-war Japan, as well as the subsequent boom decades of the urbanized, high-tech 60s and 70s.

The Tsuge myth also includes the story of an absentee father and of a rebellious youth spent in abject poverty and haunted by bouts of depression. Dreams of escape pervade it: when he was 14, he was arrested by the coast guard for stowing away on a ship bound for America; when he was 20, he attempted suicide after a failed romantic relationship.

His 24-page story from 1973, ”Oba denki mekki Kôgyôsho” (“Oba’s Electroplate Factory”) is directly based on his brother’s experiences working at a factory as a child, having left school after the primary years. We witness the appalling work conditions and the inevitable cadmium poisoning suffered by the workers. One older worker literally excretes his life through a hole in floor of his shed while his children look on.

In contrast to the people around him, the young protagonist—who is portrayed with a mixture of sarcasm and genuine affection—is characterized by indomitable optimism. This despite the severe burns he suffers one day from acid used at the factory to sharpen shrapnel for American bombs. Even his eventual abandonment at the hands of the female supervisor, when she finally leaves the factory along with its only other surviving worker, does not faze him.

Among Tsuge’s most finely realized self-portraits in comics is the 200-page graphic novel Munô no Hito (’The Man Without Qualities’, with a possible nod to Robert Musil?). It was serialized in the magazine Comic Baku from 1984-1985 in 6 separate episodes and narrates the life of a man incapable of providing for his family. He dreams of making things work, and his dreams as rendered on the paper are beautiful, but reality ruthlessly confounds him. He simply cannot succeed. He is unable to take responsibility and continually rejects his only real source of income, comics, as a possibility. Instead he attempts unsuccessfully to make his way as a dealer, initially of second-hand cameras, then of rocks found along the banks of the nearby river. This “business” encapsulates the hopelessness of his industry and is—as his increasingly dejected wife never hesitates to tell him—emblematic of his life as a whole.

Tsuge renders this life in fragments, chapter by chapter. Each episode is self-contained, but when read together they form a beautifully structured narrative. The presentation, whether between chapters or within them, is not linear and a clear chronology never emerges. It opens at the nadir of the story, a moment of almost total hopelessness. The man and his wife are utterly estranged—Tsuge never show us her face, and in a heartbreaking scene she passes him on the street as if he were a stranger. The night closes in, the shrieks of the crows sound to him like “Looooser! Looooser!”, and he is drawn to leap into oblivion. His only lifeline is his young son, who every night comes down to his rockseller’s stall on the riverbank and takes him home before dark.

In later chapters we return to earlier times and come better to understand the disintegration of the small family. We meet them in happier times, when moments of warmth, tenderness and fun still occurred, despite the boy already exhibiting disturbing signs of neurotic behavior. We see the wife’s face, but already sense that her esteem for her husband is on the wane. Awareness of where it is all going make these passages painful reading.

Tsuge here renders the curse of poverty as intensely as in his earlier stories, but he is less emphatic in his social critique. The central tragedy is internal, self-inflicted—the story is a subtle, grinding portrayal of depression as both a mental state and a physical condition. It never delivers a conclusive diagnosis, being more self-contemplation than self-criticism. It describes a person in crisis by means of stark realism joined to flights of dreamy allegory, and typically for Tsuge, its poetic tenor is borne of equal parts irreverence and empathy. A fairly long, rather flowery exegesis on Buddhist notions of equilibrium and salvation between the protagonist and an acquaintance is rudely interrupted by a drawn-out fart from the latter’s sleeping wife.

And finally, parable of an alcoholic, flea-ridden mendicant who breathes his last breath reciting an enigmatic poem, his body covered in his own dried-up excrement, becomes the metaphorical shot in the dark that lifts the story from where it started, letting it transcend precariously its own circularity.

Tsuge’s work is animated by this combination of prosaic entropy and contemplative longing. His pessimism is tempered by fleeting moments of possible beauty. Sometimes the feeling is one of nostalgia, as if borne by a sense of loss, but ultimately his position seems to be that beauty, though acutely present, is unfathomable.

A particularly fine evocation of this is the 15-page 1967 story ”Akai hana” (”Red Flowers”). The protagonist is a young girl who has dropped out of school to manage her family’s tea house in a beautifully lush corner of the land, visited only by a lucky few. A man from the big city—apparently a wistful stand-in for Tsuge himself—is there to fish and comes to observe the unfolding relationship between the girl and a little boy two years her junior. He teases her because of her emerging pubic hair and voyeuristically observes her first menstruation. She lets the blood run into the river where it appears to transform into beautiful, red flowers before it disappears into a maelstrom.

With its vibrant depiction of the surrounding environment, its nostalgic but ultimately optimistic tone, and its loving portrayal of its characters, “Red Flowers” seems a distillation of the beauty present in all of Tsuge’s work, even the bleakest. As always, sex is an incontrovertible presence; as in “Screw-Style”, it is the catalyst that resolves the story. In contrast to that dark masterpiece, however, it is here the heart of a poetic celebration of change as a human condition. Tsuge drew these two stories within a year of each other and they combine to reveal the promise of his art.

Tsuge in translation

”Red Flowers” (”Akai hana”, 1967), in Raw vol. 1 #7. New York: Raw Books, 1985.

”Oba’s Electroplate Factory” (”Oba denki mekki Kôgyôsho”, 1973), in Raw vol. 2 #2. New York: Penguin Books, 1990.

”Screw-Style” (”Nejishiki”, 1968), in The Comics Journal #250. Seattle: Fantagraphics, 2003.

L’Homme sans talent (Munô no Hito, 1984-85). Angoulême: Ego comme X, 2004.

Links

List of works (Japanese language)

Great 1987 interview with Tsuge (French language)

Béatrice Marechal on Tsuge from The Comics Journal 2005 Special Edition.

Domingos on Tsuge and “Nejishiki”.

Gilles Laborderie on Munô no Hito for Indy Magazine.

Images from Tsuge’s early comics.

__________

Update by Noah: Ng Suat Tong just posted another lengthy essay on Tsuge.