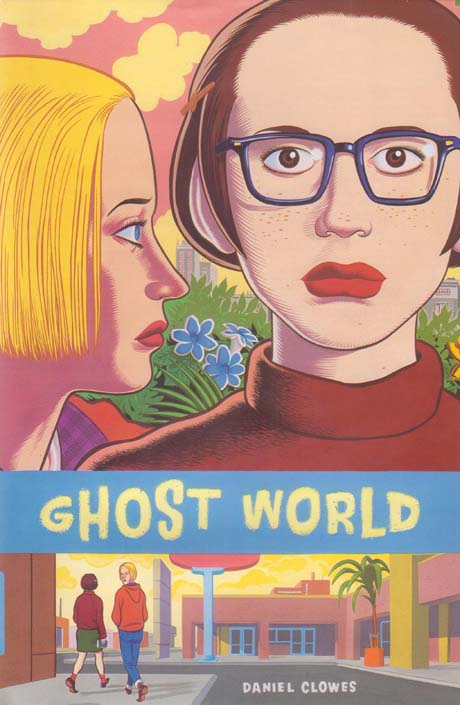

‘Show, don’t tell’ the saying goes, and that’s what Clowes does here. Ghost World, as those who’ve been reading along are aware, is the story of two teenaged girls fresh from highschool named Enid and Rebecca. Ghost World chronicles some episodic interludes in their relationship and Enid’s life.

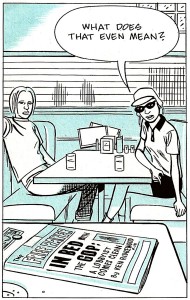

With its purposefully ugly art, limited color schemes, Satanists, cafe settings, music references, and f-bombs, this comic is painfully edgy. The whole thing might as well scream: I’m new! Different! Hip!

And maybe the art is, maybe the setting is, but honestly I don’t really care. The story is pathetically old school.

Clowes depicts the two girls, Enid and Rebecca, as being shallow shallow shallow. They lead boring, directionless lives. They like to make prank calls. They pick on each other. Enid, in particular, is full of loathing towards others. When Rebecca challenges her to name one guy she finds attractive and would sleep with she says, wait for it!

David Clowes.

No, really, she does. Self-insert Mary Sue-ism! Ewww.

It’s one thing to show a set of characters as essentially problematic and unlikeable, but if you’re going to do it, and you’re not one of the group you’re deriding, then you’d better show them accurately and not rig the game in your own favor.

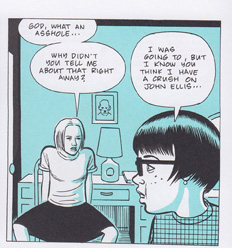

Which is why Ghost World so annoys me. Clowes’s teenaged girls don’t behave like teenaged girls. Here we have Enid telling Rebecca a story about meeting an old asshole, Ellis, and his kiddie raper friend. Ellis ‘humorously’ suggests that the kiddie-raper check her out, since she’s only 18.

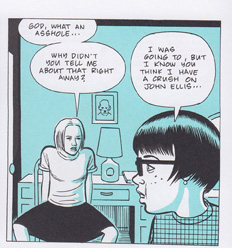

Rebecca’s response is shown below:

First of all, take a look at that body language. As someone who wears a skirt from time to time, let me tell you that girls rarely spread their legs like that while wearing a skirt. For one thing, it’s flat out uncomfortable. For another, we get nagged about spreading our legs or showing off our panties or what-have-you. Even in pants, spreading the legs is something that is usually done when one feels very comfortable and safe. It’s not something that a girl does when she’s just heard some bozo suggest a child-molester hit on her best friend.

This panel is not an accident. Look, I don’t like Ghost World, but Clowes has some drawing chops and he portrays body language effectively enough when he wants to. So what’s going on here?

A teenaged girl is not going to open her legs wide in a ‘take me big boy’ response, so why is she drawn this way? I can only assume that Clowes thinks a girl would have that response or because he wants to titillate the reader with Rebecca’s spread legs. Either option is unpleasant.

Then there’s the “lesbo” masturbation scene.

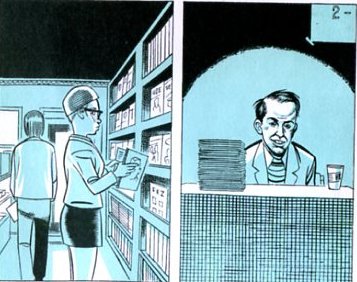

I’ve noticed that one of the ways Clowes mocks Enid is by having her mock people for something and then later having Enid do that mockable thing herself. Enid makes fun of a guy who she used to have something of a teen-romance with in high school. She says that he probably called her and jacked off while she talked. Mock mock mock ew say Enid and Rebecca. Then Enid visits an adult bookstore and picks up a fetish Batwoman hat and calls to tell Rebecca about the adventure. While on the phone with Rebecca, Enid takes off all her clothes and gropes herself while looking in the mirror (but doesn’t tell Rebecca). Mock mock mock.

It’s this weird circle jerk, but it doesn’t ring true. It comes off to me as something Clowes wants to think teenaged girls do, much in the same way that the high school boys I knew hoped the girls in the gym showers got up to steamy hanky panky. Never mind that in reality gym showers were places of horror, shame, body-fat hatred, silent prayers that you weren’t having your period (and if you were, that no one would find out–good luck with that) and tears. To the guys it was all a happy fantasy of hot girl on girl action.

Why is Clowes doing this? I say it’s to do two things at once: make fun of Enid for being a jerk and to fantasize about her and Rebecca in a sexual way.

Here’s a thought experiment. Take out the reference to Sassy and replace it with Lucky. Remove the punk green hair and replace it with a blonde ponytail. Switch the swearwords from fucking cunts to snooty bitches. Remove Bob Skeeter the astrologist and replace him with Ned the computer nerd. Pretty soon, if you took away the hipster faux-literary trappings and replaced them with mainstream teen story trappings, you’d have a boring and cliched tale of a couple of teenage girls who everyone loves to hate (and wants to date).

But maybe it’s not as OK as it used to be to hate girls just because they’re blond and pretty and not fucking you. So, instead of going that route, make the girls “real” by changing their outfits and the bit characters and the scenery. Then it’s not a cliched misogynistic screed, it becomes a “true” tale of how girls “really are”.

But it isn’t quite a tale of a guy who can’t get some, is it? No, because Clowes draws the main character wanting him. How much more proof could there be that this is a story about girls who are wanted/hated and the line between those two things?

There’s a fine literary tradition all about how women are shallow creatures and female friendships are suspicious and smothering. But if you’re a old dude perving on the sweet young things when you’re arguing it, it looks a teensy bit suspicious, is what I’m sayin’.

So let’s take a look at the so-called emotional growth and story progression of their relationship. What do they say and what do they do? Enid is thinking of going to college (to become someone new) and Rebecca decides to travel with her. What do they say about this? That it’s unhealthy.

Let’s take a look at that. It’s unhealthy for a friend to accompany a friend on a quest to become someone new.

Do you think that’s true? Because I sure as hell don’t. I’ve gone on several quests to make myself better, move someplace new (emotionally or physically), and been enriched and enlivened by the people who are by my side, traveling those paths with me. But Clowes, speaking through his characters, labels this as kind of creepy.

So what, exactly, does Clowes display as Enid’s growth? What is her progression?

If we take a look at the final pages, we see Enid in a new outfit. We’ve learned in this comic that changing outfits means changing who you are (at least for Enid), so let’s take a look at what’s she changed into. She’s well-groomed, with smooth hair done like Jackie Kennedy, and she’s wearing a neat, fifties housewife ensemble and carrying a hatbox shaped purse. Examine that for a moment.

Does this hark back to a desire on Enid’s part? Not as mentioned/drawn in the text, so we’re left interpreting the image in the way our society means it. Nothing says housewife quite the way a fifties outfit does. Is there anything (besides June Cleaver) that fifties suits and haircuts bring to mind, visually speaking?

Not that I know of.

What is this journey, anyway? It’s a journey of Enid’s current life, and it ends when Enid steps on a bus. What does that symbolize, within the context of story that Clowes has built? Erasure of self. Clowes likes to talk about it as creating someone new, but again and again he denies that Enid wants to be anyone specific. At the end, presumably after her emotional change (indicated by the dress, the diner voyeur scene and the bus) he gives her no identity except that of a very stereotypical fifties housewife.

That’s the “growth” that he lays out.

Ponder that for a moment and ask yourself whether it is, in any substantial way, a positive view of Enid. A positive view of girls, period. Whether it is anything besides the author saying, “Girls like Enid eventually cease to exist“. Not only does the author change them (into something trite), the girl herself wants to be anyone but herself. Herself is so awful she cannot be.

That’s a pretty hateful message when you get right down to it, and I cannot look at that as growth, as anything besides old fashioned misogyny and a desire to turn Enid into, bluntly, a wife. A person who exists not for herself, but who exists in relation to a man.*

But maybe I’m wrong. It’s been known to happen, and a single outfit is a small thing to base an entire textual interpretation on, right?

Right. Let’s look at the diner scene, which is the last line in the book, and the closure of Enid’s relationship with Rebecca. What does Enid say?

She says, “You’ve turned into a beautiful young woman.”

A beautiful young woman.

Look at those words. Consider the perspective of them.

Who is saying this? What is the relation of the woman in those words? To what aspect of the person are these words referring?

Enid (or Clowes through the character of Enid) considers this the mark of passage for Rebecca, the outside view, the praise. But what kind of praise is it?

It’s the praise of someone outside the woman, wanting her sexually, and has nothing at all to do with the woman’s internal desires, personal happiness, emotional growth, interests, community, relationships, or personhood. No, to say ‘She’s a beautiful young woman’ is to say she’s sexually desirable by an outsider.

And you know, as a bland statement of fact, it’s not so bad. But as a statement of a woman’s journey through a friendship and her creation of a new ideal self? That’s really fucking shallow, objectifying, and creepy.

This is not a tale of powerful female friendships post highschool. Nor is it a tale of emotional growth. It’s the same, tired story of how girls are shallow and their friendships are incestuous and unhealthy and most importantly how they need to become not-themselves. Gee, that’s deep. I’ve never heard teen girls and what they care about called shallow before! How original!

* Yes, I’m well aware that plenty of women are happily married. That’s not what I’m talking about, so let’s not go there. What I’m talking about is defining a woman only as her role in regards to men.

Note number two: I was an odd clothes wearing weirdo who read strange magazines, once upon a time, so I’m well familiar voices and inner worries of this group. Just so you know.