Editorial Update: This is the third post in a roundtable on Ghost World. The first two can be found here and here.

________________________

I read “Ghost World” for the first time last week, and my initial reaction was fairly positive, though it was hard for me to explain why. As I thought more about it, I realized that my appreciation for the comic had little to do with the art. Nor did I care much for the episodic stories, which ranged from mildly amusing to kinda dull. The most appealing aspect of “Ghost World” was the main characters, Enid and Rebecca. And much of their appeal is due to how effectively Daniel Clowes panders to a specific demographic that I belong to: geeks.

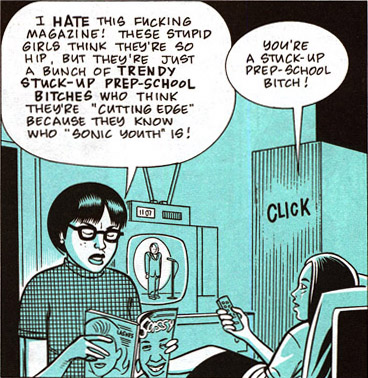

It’s easy to see why geeky comic readers love this book. Enid and Rebecca are both social outcasts. They’re alienated, unmotivated, but seem cleverer than everyone else. They’re constantly looking for ways to relieve their boredom (which is difficult when living in an ugly suburban sprawl). Enid, in particular, has mastered the ironic appreciation of pop culture detritus. I can see Enid and Rebecca as the type of kids who would go to a comic convention just to make fun of the fat guys dressed like Green Lantern. And like all teenagers, they’re obsessed with sex but uncomfortable with the idea of adulthood.

If I had read “Ghost World” when I was 18 it would have probably been my favorite comic of all time. I was a typical Gen X’er nerd, an insufferable combination of self-pity and intellectual arrogance. Maybe Daniel Clowes went through a similar phase, because that also sounds like a good description of Enid. And that’s why I found it odd when Kinukitty argued that Enid was unrelatable, because my inner geek had no trouble relating to her. Admittedly, there’s an underlying narcissism in Enid’s appeal, and that can be very off-putting to some readers. My appreciation for the character of Enid is connected with a nostalgia for my late teens. Clowes makes this easy for me, because Enid is not some unique gem of a character, and there isn’t much that gets in the way of my identification with her. She’s an archetype of geeky disaffection, a bundle of adolescent hangups and amusing idiosyncrasies.

Much of the comic is devoted to exploring the ennui of middle class geeks, and the story is constantly on the verge of succumbing to a navel-gazing sigh. Clowes is a better writer than that, however, which is why “Ghost World” ends the way it does. But even the ending, where Enid gets on the bus to Anywhere but Here, feels calculated to deliver maximum satisfaction to grown-up geeks. In Enid, geeks find an avatar who breaks free of her post-adolescent stasis and embraces maturity. But it’s a maturity without content, which invites that the reader fill in the blanks with their own experiences. In short, “Ghost World” gives comic readers the best of both worlds: a wistful look back on their awkward teen years followed by the endorsement of their adulthood.

My opinion of “Ghost World” is mixed. The jaded, grown-up part of me can recognize that, beneath all the hype, “Ghost World” is nothing more and nothing less than well-crafted pandering to the core demographic of indie comics. On the other hand, my inner geek is easy to please.