This is a belated entry into the Jaime Hernandez roundtable…and so, in Part II (Update: now online here) I’ll be discussing Locas. Forgive the circuitous approach…

__________

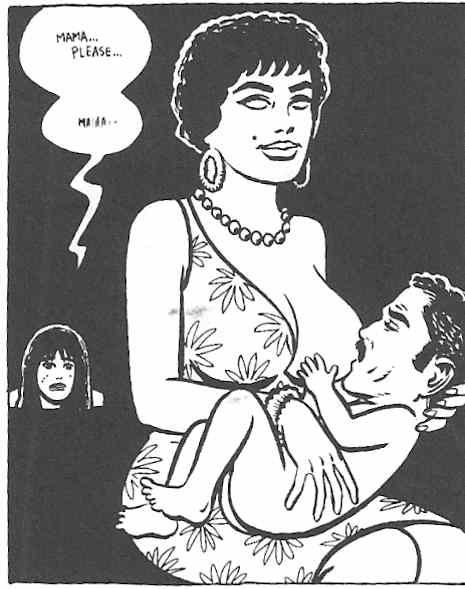

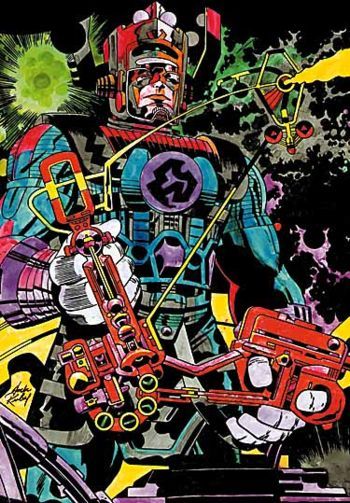

Some months (or possibly years) back, in a roundtable devoted to Charles Hatfield’s book, Alternative Comics, various HU luminaries and commenters discussed the tendency of Gilbert Hernandez to employ, exploit, and self-reflexively examine a variety of sexual fetishes. In particular, though Hernandez is sometimes praised for the depth and complexity of his female characters, there is also a tendency in his work to linger upon, obsessively expose, and/or overemphasize particular “surface” elements of the female anatomy. In the case of his most frequent protagonist, Luba, and her mother, Maria, the fetishization of breasts might be said to reach an extreme. In the roundtable discussion and comments, the term “fetish” was used without any particular theoretical apparatus, and there is no reason why such an apparatus is fundamentally necessary. Certainly, we all know that when we talk about a “fetish,” we are discussing some object that takes on a surprising amount of significance and importance, often without any obvious reason. In the realm of the sexual, a shoe fetishist finds outsized sexual pleasure in a shoe, despite the “normal” social tendency to not view footwear as a necessarily sexual object. Though female breasts are quite often a focus of sexual attention in our (Western, American) society, it is certainly the case that there seems to be no intrinsic reason why they must be so and the heterosexual male’s obsession with women’s breasts may be attributed to a “cultural fetish” of sorts, one that Gilbert Hernandez exaggerates, but certainly does not invent.

Typical understandings of breasts as a cultural fetish might advert to a kind of pseudo-Freudianism, which gestures to Freud without reading his work very deeply. Certainly, anyone who knows anything about Freudian psychoanalysis, knows that it hinges around the notion of the Oedipus complex, or sexual desire for the mother, combined with competition with the father for her love. According to Freud, initial pleasures come principally orally (from eating) and anally (from excreting), before a subsequent move to genitally centered pleasures. Because a baby’s first “oral” pleasure comes from the mother, and at the mother’s breast, Freud argues that the child then “associates” pleasure with the mother and so, when pleasure itself becomes genital, sexual desire too is first directed at the mother. Likewise, since the breast is the first locale of oral pleasures (only for breast-fed babies, obviously…but bottles don’t preoccupy Freud overmuch), it should be no surprise that breasts become a locus of genital/sexual desire (again, through the “association” of varying kinds of pleasure). I would make no argument here for the biological or scientific “accuracy” of Freudian psychoanalysis, but merely note how the fetishizing of breasts might, in a Freudian context, seem like a “natural” one…part of the prescribed journey through the Oedipal cycle and the “natural” fixation on breasts and orality that precedes genital sexuality.

Neither Freud’s nor Hernandez’s version of fetishism is so simple, however, and, in fact, in Freud’s essay on fetishism, breasts don’t get so much as a mention. Instead, Freud defines any sexual fetish as “a substitute for the woman’s (the mother’s) penis that the little boy once believed in and—for reasons familiar to us—does not want to give up” (842). It no doubt comes as a surprise for those uninitiated into psychoanalysis that women, or our mothers in particular, have a penis, but of course Freud is not really saying she does, or not in so many words. Rather, he argues that there is a point in early childhood that boys, at least, believe that everyone has a penis, and so they are shocked when they learn, by hook or by crook, that their own mother does not. The acquisition of this knowledge, the knowledge of sexual difference, is central to the journey through the Oedipus complex, because it is when a boy learns that his mother does not have a penis that he realizes that his own may be in imminent danger. That is, the boy apprehends his mother as a castrated (wo)man instantiating his own “castration anxiety.”

The logic of such a claim is dubious, of course. Is there any particular reason to view a woman this way, as a man “lacking a penis” and therefore not whole? The answer is, of course, “no,” and the preoccupation with the phallus as the seat of all that is whole, central, and important in life is part and parcel of a long history of patriarchal thinking which feminists (even feminists interested in psychoanalysis) rightfully reject. Nevertheless, in the context of Gilbert Hernandez’s “fetishist” (or, at least, fetish-y) comics, and eventually his brother Jaime’s as well, it is useful to follow Freud just a bit further.

According to Freud, when a boy is faced with the supposed castration of his mother, it plays a significant role in the repression of his desire for her. Since he has been in competition with his father for the love and affection of his mother from the outset, the realization that his mother has been castrated introduces fears by the child that the castrating was done by dad himself. This possibility makes the boy a) fear for his own penis (if dad castrated mom, what is to stop him from castrating his son, especially when they are in competition for mom’s affection?), and b) repress his desire for his mother. With the revelation that dad is strong and, apparently, ruthless (willing to castrate his enemies at a moment’s notice), the idea of continuing to compete with him for mom’s affection becomes not only less attractive, but actively terrifying, and so, the boy will repress his sexual desire for his mother, forgetting it altogether and redirecting it onto a more socially appropriate object, simultaneously entering the more “appropriate” social world where incest is unacceptable. In most cases, argues Freud, this is what occurs. In some cases, however, a child is not quite ready to give up the mother’s phallus, and instead “replaces” it with a fetish object. Says Freud, “the horror of castration has set up a memorial to itself in the creation of this substitute” (843) and the substitute will usually be linked to the moment of revelation in some way.

Thus the foot or shoe owes its preference as a fetish—or a part of it—to the circumstance that the inquisitive boy peered at the woman’s genitals from below, from her legs up; fur and velvet— as has long been suspected— are a fixation of the sight of the pubic hair, which should have been followed by the longed-for sight of the female member; pieces of underclothing, which are so often chosen as a fetish crystallize the moment of undressing, the last moment in which the woman could still be regarded as phallic. (843)

Interestingly, Freud argues, then, that the fetish allows for the fetishist both to know and acknowledge the fact that his mother has no penis (to know and acknowledge sexual difference), while simultaneously repressing or denying that fact. Allowing for a replacement for the mother’s penis allows for the fetishist to retain the sexual bliss of the first attachment to the (phallic) mother, while also displacing it away from the mother herself, as well as from the penis itself, which “saves the fetishist from becoming a homosexual” (843). Here, Freud reveals himself to be a homophobe, as well as a sexist, and quite possibly a loon, interpreting male gay love as merely another displaced attraction to the phallic mother, which, he suggests, is better displaced upon a shoe, or undergarment.

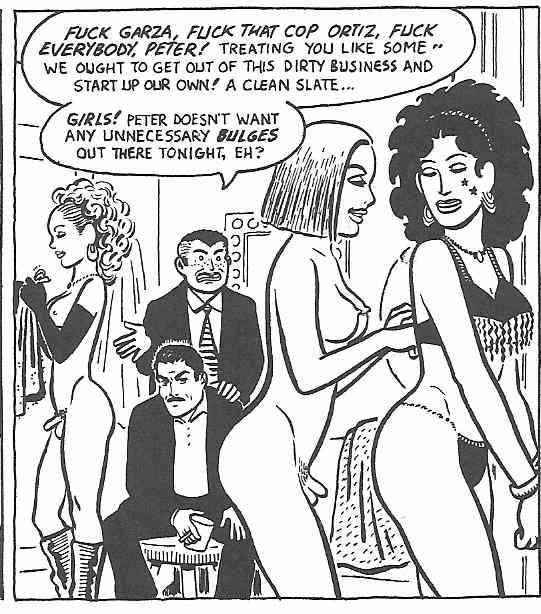

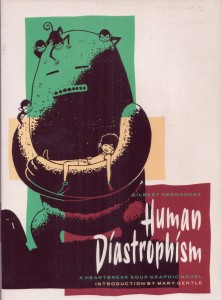

Given all the logical, political, and social problems with Freud’s argument, it seems like a waste of time to recap or belabor it here in association with the comics of Los Bros Hernandez, except insofar as this Freudian view of fetishism is courted so openly by Gilbert and therefore may help us understand and/or appreciate his work. In Poison River, Gilbert’s first post-Palomar graphic novel, Luba’s husband Peter Rio, runs a strip club whose strippers are pre-operative transsexuals, or in Freudian terms, phallic women. Significantly, Rio demands that the women tuck their penises tightly into their panties while they are dancing, so that they are invisible. Any sign of a bulge offends Rio and, it seems, his fetish, though if he truly did not wish to see “phallic women,” he could presumably run a more conventional strip joint.

In all of this, Rio fulfills Freud’s claims about fetishists to the letter. Fetishists, says Freud, must maintain two “incompatible” claims, “the woman has still got a penis” (which allows the fetishist to retain the notion of the perfectly whole “phallic mother” who was the object of his initial desire) and “my father has castrated the woman” (which allows him to integrate into society, to break away from his family, and direct his desires elsewhere) (844). That is, fetishism allows the man to consciously enter the social world and participate successfully in it, while still being able to fulfill his deepest (unconscious) desires for the mother, and not just the mother, but the phallic mother that preceded the shock he received at the threat of castration. Freud notes how well an “athletic support belt…which covered up the genitals entirely” works as a fetish object, since it “signified that women were castrated and that they were not castrated” (844). The link of the panties of Rio’s strippers to this description seems too obvious to be further “unpacked.” Rio needs the strippers to retain the possibility that castration never occurred, but he needs the “tucking” to signify that it (simultaneously) did.

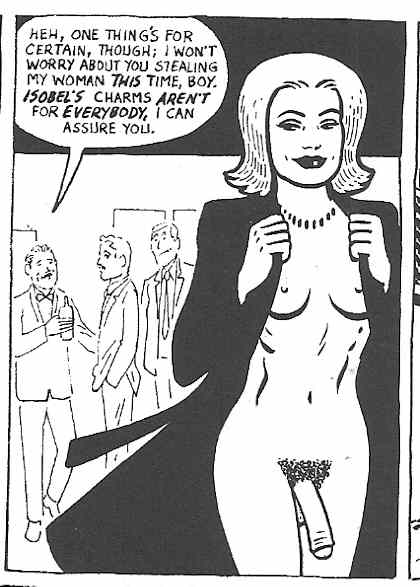

One could push this further in Poison River and in Gilbert’s work more generally, especially given that Rio’s fetish is not actually (or not only) panties, but bellybuttons, and given his involvement not only with Luba, but with her mother as well. In addition, Peter’s father, Fermin, also has an affair with both Maria and with the transsexual Isobel who later becomes Peter’s mistress. It is, in fact, a running joke of sorts that Peter is only attracted to women whom his father has had first, a clear intimation of his “mother issues” and, as Hatfield discusses, his continuing need to protect his mother from Fermin’s brutal beatings, even after his mother is long gone. Every step of the narrative, then, mirrors the Freudian one of desire for the mother and competition with the father, complicated only slightly by the fact that one of the fetishes involved is not of a different object that replaces the mother’s penis, but of the female penis itself, albeit now attached to different women, indicating further how Peter’s repression of his desire for his mother is insufficient by Freudian standards.

All of this is linked to the social and political pattern Hatfield notes in his reading of the graphic novel. Hatfield argues that much of Poison River is devoted to the attempt by Peter, Fermin, and others to maintain a corrupt “public sphere” of drug trafficking and gang warfare, while “protecting” women from such a world by confining them to an “idealized conception of the home” (Hatfield 90) and keeping them in the dark about male activities. That is, Peter and his “men” enforce “sexual difference” in a variety of paternally protective (i.e. sexist) ways, even as the book indicates the ways in which such an effort is doomed to failure. The drug use of Luba and her girlfriends, for instance, indicate the ways in which it becomes impossible to insulate women from the dangerous “masculine activities” of the public sphere, as does the way in which women serve as pawns or objects in the world of masculine competition. Without their own knowledge, for instance, Luba, Maria, and Isobel all become objects over which Peter and his father compete sexually. They are, then, part of the world of masculine competition (and capitalist acquisition), even when they are unaware of their role within it. Likewise, as Hatfield points out, even the stereotypically feminine world of childbirth and childrearing is tainted by the masculine world of crime and “business,” in the fact that Peter buys a child for Isobel on the black market, a purchase he must later “pay for” in kind.

These thematic reminders of the impossibility of completely separating the worlds of the two genders is complemented by the consistent references to the world that, in Freudian terms, exists before the introduction of sexual difference. The “phallic mother” is an exemplar of a fantasy world that predates the necessity of dividing mother from child (esp. mother from son), male from female, and public sphere from private. While, on one hand, Peter vigilantly enforces social and public gender divisions, in his private/sexual life, he is continually attempting to re-unite the two genders, fixated as he is on the fantasy of the “phallic mother.” While he, like Freud, continually worries that his sexual behavior may be read as “queer” (insofar as he is both literally and metaphorically constantly desirous of the penis which is both missing and present), it is also clear that this “queerness” is itself a utopian desire for a world that predates the gender divisions he also polices.

When, in Palomar and “beyond” so many of Gilbert’s characters reveal themselves to be “queer” in some fashion, attracted to both genders (despite often years of strictly hetero- proclivities), it suggests a nostalgic hearkening back to a pre-Oedipal “queer paradise” before gender divisions, or before we became aware of them. If, after all, gender divisions do/did not exist, what can it mean to even identify someone as hetero- or homosexual? Such terms only have meaning in a post-Oedipal world and not in the paradise of the phallic mother. Poison River never suggests that it is exactly possible to return, regress, or progress, to such a paradise. Rather, the tone, as Hatfield notes, is persistently one of disillusionment and acknowledgment that the effort to retain a paradise of any kind is inevitably a losing one (whether that paradise be the matriarchal world of Palomar itself or the androgynous world of the phallic mother). However, Poison River does serve to both suggest and reveal the presence of the desire for such a paradise and its prevalence, particularly through the mechanism of fetishism. Far from being a text that simplistically fetishizes women, or particular parts of their anatomy, as objects for the male gaze, it suggests that the mere act of fetishizing blurs the divide between male and female. The fantasy is not here of an empty, mindless, female object (though Maria, at times, seems to occupy that space), but of a mother with a phallus, a pure union with a love object that precedes and blurs sexual divisions. As Freud notes, fetishism always moves in two directions, both acknowledging “castration” of the mother and the world of gender divisions which follows and disavowing such divisions, hearkening back to a pre-Oedipal utopia, wherein sexuality is polymorphous, bisexual, and incestuous. Poison River dynamically presents both the pre- and post-lapsarian worlds that are retained in the psyche in the process of fetishism. In all of this, there is an acknowledgment that an entry into the social world where gender divisions are policed and enforced is both inevitable and unfortunate, but there is also a retention of the utopian desire to transcend that inevitability.

But what does any of this have to do with Jaime Hernandez and Locas? Tune in to Part 2!

Works cited

Freud, Sigmund. “Fetishism.” 1927. The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, 2nd ed. NewYork: W. W. Norton & Company, 2001, 2010. 841-45.

Hatfield, Charles. Alternative Comics: An Emerging Literature. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2005.

Hernandez, Gilbert. Poison River. 1988-94. Beyond Palomar. Seattle, WA: Fantagraphics Books, 2007. 7-189.