Editorial Update: This is the second post in a roundtable on Ghost World. The first, by kinukitty is here.

___________________

Reading Ghost World again got me to thinking about John Barth’s nihilist novel, The End of the Road. The latter begins at a bus station; the former ends at a bus stop. And much like Barth’s protagonist Jacob Horner, Enid spends the duration of the story searching for an identity, but only succeeds in finding what she’s not. Horner is a middle-aged academic type who’s managed to think himself into a hole, not seeing any potential action as better grounded than another – sort of an infinite regress of self. Thus, he’s sitting in a bus station in a state of existential paralysis, not able to even come up with a good reason to get on a bus and leave his former (non-) life behind. The abiding gloom that pervades all of Ghost World’s vignettes, undercutting Enid’s hipper-than-thou detachment from those around her, is a sense that she’s headed to the same destination as Horner: nowhere.

I figure there must be some consilience here, since kinukitty’s main reason for not liking Clowes’ book – that it’s neither real nor funny – reminds me of Barth’s prefatory defense of his story:

Jacob Horner […] embodies my conviction that one may reach such a degree of self-estrangement as to feel no coherent antecedent for the first-person-singular pronoun. […] If the reader regards [this] egregious [condition] (as embodied by the [narrator]) as merely psychopathological – that is, as symptomatic rather than emblematic – the [novel] make[s] no moral-dramatic sense. [p. viii]

Now, I realize that if one has to defend something as funny, it’s never going to make it so to those not laughing. This is particularly true of existentialist humor, since it’s kind of the obverse of prat falls, namely only funny when it happens to me. So I’m going to stick to the reality of Enid’s predicament. The End of the Road is a bit abstract, where Horner goes through a series of fanciful psychotherapeutic treatments in search of a cure (the search is, of course, at the insistence of a psychiatrist). The most relevant of these is mythotherapy, which involves acting in a chosen character role with the purpose of having it stick through habituation – an irrational solution to a rational psychosis. Clowes treats the identity formation of teenagers in much the same way, but with a recognizant teen who, like Horner, can’t ignore the ontological arbitrariness undergirding the whole process. Just because teens regularly slip into an adult role without much of a hitch doesn’t mean that there’s not a good deal of truth in her depicted inertia.

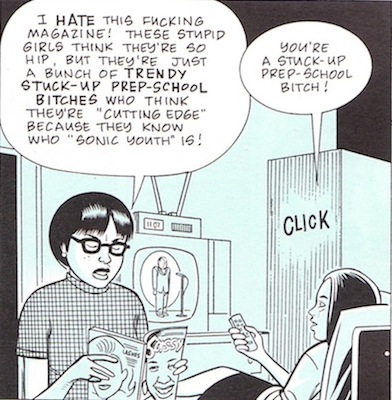

To be sure, this is a bourgeois dilemma, requiring enough leisure time to reflect on the construction of one’s identity. The working class has to learn their roles quickly if they want to endure. A day laborer in Horner’s place would simply starve. Class division is explicitly drawn out in Enid’s moribund friendship with Becky. Becky just assumes she’ll have to work after high school, whereas Enid’s dad is pressuring her into college. Enid’s intellectual background is alluded to when discussing her dad’s political interests, which she equates to sports. As she explains, since her family would be the “first ones they’d have shot” during a revolution, there’s little point to true political commitment. A choice between academia or the workforce isn’t any more significant. Becky relates to Enid’s views in much the same way that someone who desires the privileges money affords will act towards those who have always taken their wealth for granted. Becky may affect her friend’s class-based despondency, but she begins to be “cured” upon going to work. Meanwhile, Enid continues her search for an authentic self in the same manner that she began the book, analyzing pop culture:

Just like the rest of us, Enid was born into the media-saturated “Society of the Spectacle,” which makes it damn hard to distinguish the real from its image (“spectacle”). There are plenty who’ve given up the fight, claiming that the shadows on Plato’s cave are reality. It’s this crisis that leads to ironic detachment. Consider what R. Fiore calls the Warhol and Anti-Warhol Effects, which Slavoj Žižek suggests in The Fragile Absolute are two sides of the same coin. As sublime imagery became increasingly commodified (think a well-made BMW ad), modern artists increasingly focused on holding the place of Art intact (renewing or creating the “there there,” to borrow a reference from kinukitty). This was done, as a way of separating itself from the beatification of crass commercialism, by filling the spot with crud – a toilet, coke cans and the like. It has the (“Warhol”) effect of focusing the attention on the constraints, or construct, of Art, rather than the depicted object. Capital is quick to adapt, of course, so this shock tactic is of diminishing returns. If I’m correctly following Žižek’s Lacanese, this wide-scale commercial co-optation of not just the aesthetic Sublime, but pretty much anything that once gave off a sense of “authenticity,” has resulted in our no longer being able to identify ourselves in relation to these (formerly) Master Signifiers. Instead, the Self has become fractured, its consistency

[…] sustained by relationship to the pure remainder/trash/excess, to some ‘undignifed’, inherently comic, little bit of the Real; such an identification with the leftover, of course, introduces the mocking-comic mode of existence, the parodic process of the constant subversion of all firm symbolic identifications. [p. 39]

Enid Coleslaw, in other words. Her problem is that she can’t give up the Cartesian ghost; she’s looking for the old-fashioned Cogito, while living in a postmodern world. She tries to define herself by attempting paradoxically to establish defining connections through an ironic detachment from pop culture detritus, as if she can divine an auratic dimension to an anachronism like the Hubba Hubba Diner with its long-haired waiter, Weird Al. Or consider how she “authentically” dresses as a parody of 70s punk. These things can only sustain an identity if a person already believes (or acts if she believes) in their significance, which is exactly what Enid can’t do. All signifiers carry equal weight, which I suggest is hardly a flaw in her reasoning. Hell, it’s not even possible to call her condition “nihilism” without conjuring thoughts of Mike Myers on SNL, or those three phony Germans antagonizing The Dude with a ferret. Mass culture has even detached us from our detachment. Thus, Enid’s one true act (to borrow from the Lacanians again) is to get on the bus, cutting all her symbolic ties – a symbolic suicide. I’m inclined to see all of this as a good deal more than superficial tragedy. But, then again, one might point out that I have the time to blog about a comic book.