I was recently reading an essay by sociologist and comics scholar Casey Brienza about the rise of American manga titled “Books Not Comics: Publishing Fields, Globalization, and Japanese Manga in the United States” (first published in Publishing Research Quarterly.) Most of the essay is an interesting discussion of the format rejiggering by Tokyopop which triggered the manga boom in the U.S. However, at the very end, she broadens her net a bit to focus on the implications of globalization in general.

I was recently reading an essay by sociologist and comics scholar Casey Brienza about the rise of American manga titled “Books Not Comics: Publishing Fields, Globalization, and Japanese Manga in the United States” (first published in Publishing Research Quarterly.) Most of the essay is an interesting discussion of the format rejiggering by Tokyopop which triggered the manga boom in the U.S. However, at the very end, she broadens her net a bit to focus on the implications of globalization in general.

This is the great tragedy of globalization. Although globalization has changed the world in which we live dramatically, there are places within our interior worlds that even those outward changes cannot penetrate. There is an irreducible distance between different people and different cultures that globalization cannot bridge. Much of manga’s “cultural odor,” to borrow a term from Iwabuchi, is preserved intact on the level of content. But as the manga field migrates into the book field, and manga became just another category of books, like cookbooks, science fiction, or biographies, actors throughout the field will slowly lose their ability to detect that odor at all. Therefore, even though we may all be looking at exactly the same pictures and reading exactly the same prose, there is no positive guarantee that, when we do so, we are seeing anything else besides our own, forever-separate selves reflected back at us.

For Brienza, cultural imports do not change the importer; instead, they themselves are altered. Manga doesn’t make America more Japanese; instead, America simply swallows manga and turns it into plain old bland American books.

In Let’s Talk About Love: A Journey to the Center of Taste, Carl Wilson observes the same phenomena of cultural adaptation…but he sees it as a positive, not a negative. In discussing Celine Dion’s global appeal, he notes that she has to be marketed carefully and specifically to each global region. Instead of creating a one world of Dion, she has to change herself to fit each niche. Wilson writes:

Now a successful artist has to figuratively become local by fulfilling entertainment conventions in other parts of the world. It is less homogenization than hybridization of cultures. As Jan Nederveen Pieterse of the Institute of Social Studies in the Hague writes, “How do we come to terms with phenomena such as Thai boxing by Moroccan girls in Amsterdam, Asian rap in London, Irish bagels, Chinese tacos and Mardi Gras Indians in the United States…? Cultural experiences, past or present, have not been simply moving in the direction of cultural uniformity and standardization.” He suggests what we’re witnessing is a “creolisation of global culture.” It does not follow that creolization will take a standard form. Localism is ignored, as Celine’s marketers know, at peril. Likewise the global hegemony model presumes there won’t be reciprocal cultural influence on the West, but the counterevidence is all around us: Asian video-game music, for example, is arguably among the most pervasive influences on young pop musicians now. And as Pieterse points out, with the exception of isolated indigenous groups, civilization and hybridization have been synonymous for centuries.

Canadian singer Celine Dion and Japanese signer Juna Ito

Canadian singer Celine Dion and Japanese signer Juna Ito

So where Brienza laments the hybridization and adaptation of borrowed cultural objects, Wilson celebrates it. Where Brienza experiences a loss of manga’s unique cultural smell, Wilson argues for the joyful blending which results in Asian video game music taking on an altogether new odor in an American context.

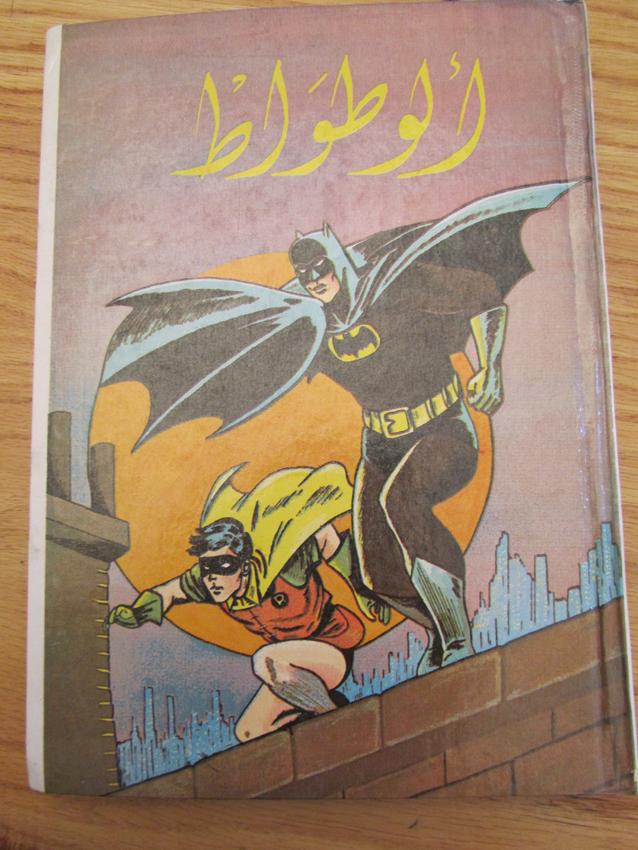

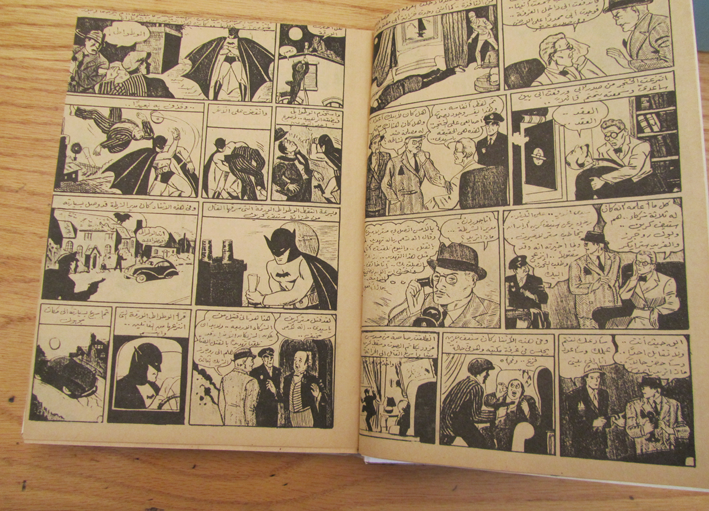

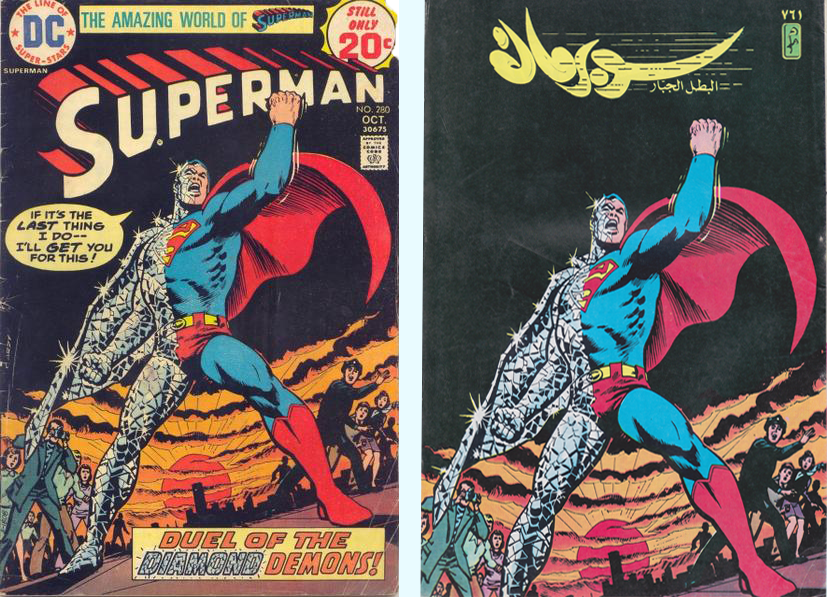

As a final take on globalization, here’s Nadim Damluji’s essay about Mickey Mouse in Egypt, written a while back on HU. Nadim discusses an Uncle Scrooge story about Egypt which was reprinted in an Egyptian comic.

The Western ducks discover a historical landmark that the Disney Arabs were incapable of finding on their own and what naturally follows their act of discovery in a foreign land is their immediate sense of ownership (Christopher Columbus much?). Furthermore, we as readers are lead to believe that the pyramids do not possess inherent value for their historical and cultural significance, but only for their ability to hold potential treasure. You see, without this treasure it wouldn’t have been worth digging out the pyramid, not worth hiring the cheap Arab labor. Lastly, we see the popular trope of Pharaonic culture being used as shorthand for all of Egyptian culture. In other words, traveling to Egypt for the Ducks is traveling into the past, not into a different contemporary culture.

Ultimately, I believe the real harm of this story is that it was tucked within the pages of a comic’s magazine that had Mickey wishing young readers Happy Ramadan or celebrating Mawlad on the cover. Mickey was localized insomuch as he could help Disney sell more comics globally, extending their commercial reach deep in to an emerging comic’s market. To be an avid Miki fans means to be an avid internalizer of the importance of capitalism and hence a way of seeing the world that makes certain countries first and others third. Mickey Mouse certainly has a big place in the history of Arab comics, but I believe it is a history whose depth we must challenge and whose psychological harm may be immeasurable.

Against Wilson’s joyful vision of hybridization, Nadim sees the same old hegemony. And where Brienza mourns the fact that cultural objects don’t change people, Nadim mourns the fact that they do. For Brienza, manga is altered so much that it loses its foreign flavor; for Nadim, Uncle Scrooge is given just enough foreign spice so that Egyptian readers can be poisoned by it.

So is globalization bad because it does not make us more alike? Is it good because it does not make us more alike? Is it bad because it does make us more alike? Or (as a possible fourth position) is it good because it makes us more alike?

Or, to put it another way, is the world better if people are more alike or less alike? And how does globalization affect that?

Philosopher Alain Badiou argues that these are the wrong questions. In his book Saint Paul: The Foundation of Universalism, Badiou insists that, in terms of the movement of global capital (both economic and, presumably, cultural), homogeneity and diversity are not in opposition. They’re the same thing. Wonderful hybridized Arab Mickey and sneaky Mickey hegemon are not opposed — they work together.

Our world is in no way as “complex” as those who wish to ensure its perpeturation claim. It is even, in its broad outline, perfectly simple.

On the one hand, there is an extension of the automatisms of capital, fulfilling one of Marx’s inspired predictions: the world finally configured, but as a market, as a world-market. This configuration imposes the rule of an abstract homogenization…. For capitalist monetary abstraction is certainly a singularity, but a singularity that has no consideration for any singularity whatsoever: singularity as indifferent to the persistent infinity of existence as it is to the evental becoming of truths.

On the other side, there is a process of fragmentation into closed identitities, and the culturalist and relativist ideology that accompanies fragmentation.

Both processes are perfectly intertwined. For each identification (the creation or cobbling together of identity) creates a figure that provides a material for its investment by the market. There is nothing more captive, so far as commercial investment is concerned, nothing more amenable to the invention of new figures of monetary homogeneity, than a community and its territory of territories…. What inexhaustible potential for mercantile investments in this upsurge — taking the form of communities demanding recognition and so-called cultural singularities — of women, homosexuals, the disabled, Arabs. And these infinite combinations of predicative traits, what a godsend! Black homosexuals, disabled Serbs, Catholic pedophiles, moderate Muslims, married priests, ecologist yuppies, the submissive unemployed, prematurely aged youth! Each time, a social image authorized new products, specialized magazines, improved shopping malls… (All italics are Badiou’s; ellipses are mine.)

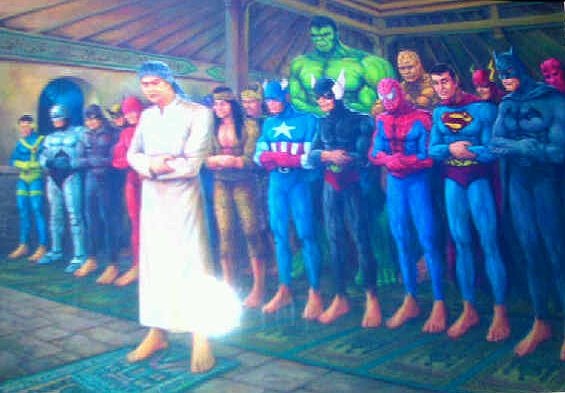

So, for Badiou, Celine singing first in Spanish then in Japanese is not a sign that hegemony has been defeated. It’s simply the flip side of the universalism of capitalism; the reduction of every individual soul to a marketing demographic. Similarly,a truly Egyptian Mickey Mouse (or truly Muslim superheroes) would not resist the logic of Western hegemony; it would simply reinscribe the identity of “Arab” on which (with all other identities) Western hegemony depends. The world is one giant bland glob, but not because, as Brienza would have it, we our trapped in our own national identities. Rather, it’s because all identities are the same identity. The lack of smell when you read manga is not a product of Americanization. Rather, the lack of smell is the result of the fact that an identity based on reading manga, whether Americanized or not, is an identity that it entirely permeable by the market.

So if, for Badiou, homogeneity and heterogeneity are the same thing, what exactly is the alternative? Well, among other things, I think he’d probably like us to ignore “culture” all together (he has acid things to say about the flattening of “art” into “culture.”) But more than that, he argues for the primacy of the Event.

The Event for Badiou is something like a miracle and something like a paradigm shift; Paul’s revelation on the rode to Damascus is his exemplar. Subjects do not experience or create the Event, rather they are created by it, and remain subjects to the extent they keep faith with it. Childbirth makes you a mother; having your mother shot makes you Batman. The Event, and your continued investment in the event, is who you are.

In the wake of the Event,individual differences are neither obliterated nor homogenized. Rather, they are accepted without being fetishized or even especially emphasized. So, for example, in Twilight, whether a vampire is white or black, male or female, is unimportant, not because those differences vanish, but because the vampire’s subjectivity is created by the Event of the transformation.

Neither Jew nor Greek, neither male nor female in vampirism.

Neither Jew nor Greek, neither male nor female in vampirism.

Similarly, Badiou points out that for Paul whether Christians were circumcised or uncircumcised made no difference. Thus, Badiou argues, for Paul, Christianity was not a sectarian identity among many, but an insistently universal human subjectivity, available to all through faith in the Resurrection, rather than through coercion or insistent self-demarcation. (Badiou, presumably, hates the Inquisition and Christian pop about equally.)

Badiou’s formulation raises perhaps as many questions as it answers. As just one example —how can you tell a sectarian identity from a universal one? Aren’t the vampires in Twilight themselves essentially a subculture? Isn’t Christianity an identity? Moreover, Badiou bases his whole thinking on idea that the Event constitutes Truth — but his paradigmatic Event is the Resurrection, which (as an atheist) he insists is false. So how exactly do you tell if the Event is true? And if Christianity was not universal because it was true, why was it universal?

Still, arguing with Badiou is, I think, a helpful corrective to arguments about globalization, which can slip rather quickly into disputes about the ideal purchasable cultural product. For Badiou, such managerial fiddling at the marketing margins is a depressing simulacrum of utopian thinking. If we’re going to dream, why not imagine a world where our souls aren’t for sale — where, as Bert Stabler said in a recent comment, “everyone can create shared institutions that aren’t niche markets or normality factories.”

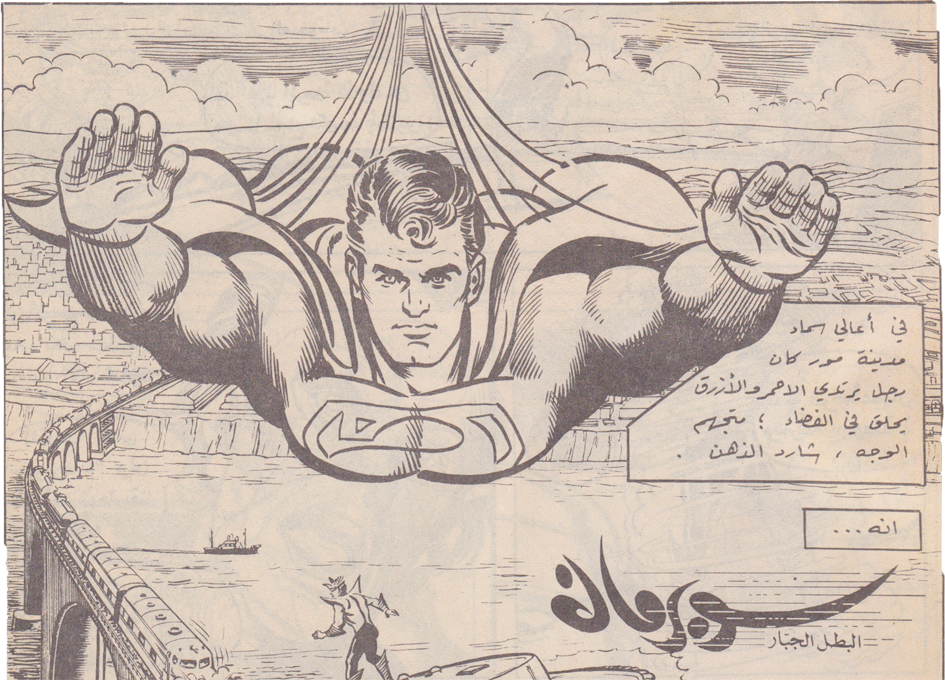

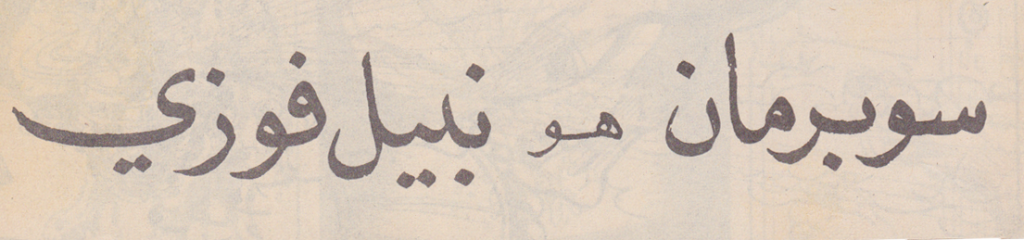

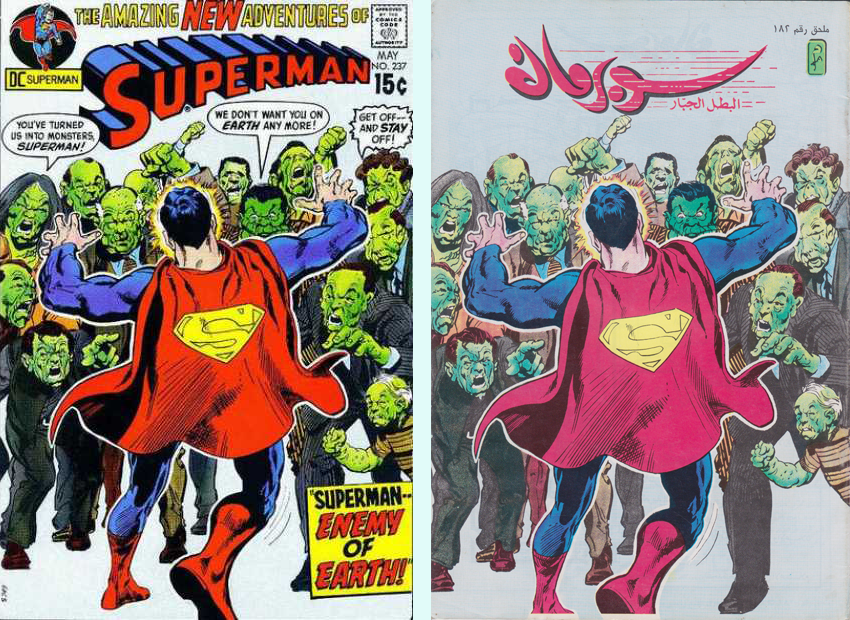

English covers via the archive at

English covers via the archive at