Godard’s La Chinoise (1967) presents the story of the “Aden Arabia” collective, a group of five students from the University of Nanterre who have borrowed an apartment for the summer as a space where they can co-habitate according to the rigorous tenets of Marxist doctrine. The five students are Guillaume (Jean-Pierre Léaud), a flamboyant actor interested in revolutionary theater; Véronique (Anne Wiazemsky), Guillaume’s lover, a philosophy student willing to use terrorism to bring about revolution, and most likely the Mao-besotted “Chinese Girl” of the film’s title; Serge (Lex de Brujin), artist and eventual suicide; Yvonne (Juliet Berto), a proletarian from the French countryside who sometimes turns to prostitution (that old Godard theme again) to support the commune; and Henri (Michel Semeniako), Yvonne’s lover and the member of the commune closest to the French Communist Party’s brand of “humanistic,” non-violent socialism. (Henri is, in fact, eventually kicked out of the Aden Arabia cell for being too soft.) La Chinoise is loosely organized around four interviews that Guillaume, Yvonne, Véronique and Henri give, in that order, to an off-screen interviewer whose voice is sometimes audible on the soundtrack. The narrative of the film, fragmented though it is by Godardian digression, involves the students’ increasing acceptance of Véronique’s program of revolutionary violence. The results of this program are Henri’s expulsion from the commune because of his unwillingness to resort to terrorism, and Véronique’s murder of a man she mistakes for a reactionary Soviet politician. (Serge commits suicide to cover up Véronique’s culpability—before he shoots himself, Serge takes responsibility for the assassination in his suicide note.) The film ends with the apartment reclaimed by its bourgeois owners, as Véronique admits (in voice-over) that the Aden Arabia commune represented only “the first timid steps of a long march.”

“Godard : le plus con des Suisses pro-chinois !”

In many scenes at the beginning of La Chinoise, the students insist that their version of Marxism/Leninism/Maoism is better and purer than the revisionist cultural and political movements of the established Left. In the third shot of the film, Véronique proclaims that any trace of liberalism in the commune would “rob the revolutionary ranks of compact organization and strict discipline”—and soon afterwards Serge carries Henri into the apartment and tells his comrades that Henri’s been beaten by commandos from the French Communist Party. While Véronique comforts Serge, Guillaume says, “Being attacked by the enemy is a good thing, because it proves there’s a clear distinction separating us.”

But this distinction is more porous than Guillaume believes. Several critics note that La Chinoise portrays the students ambiguously, praising them for their enthusiasm even while revealing their dearth of workable ideas for political change. Pauline Kael describes the students of the commune as

infantile and funny—victims of Pop culture. And although [Godard] likes them because they are ready to convert their slogans into action, because they want to do something, the movie asks, “and after you’ve closed the universities, what next?” (Going Steady 84).

Further, the commune is also compromised by a rift between the students’ professed allegiance to Maoism and their actual everyday behavior. Although the students consider themselves revolutionary, the commune is a site where Yvonne—the member of the cell from the lowest social class—is saddled with the bulk of the household chores. Also, Godard goes to great pains to show that the students are ignorant of Marxist theory and infatuated with the distinctly non-revolutionary attractions of popular culture. These contradictions give new meaning to the film’s injunction to change the world “on two fronts.” In a key scene, Véronique and Guillaume listen to Serge lecture about the need to struggle on two fronts—the political and the aesthetic—to bring about revolution, but Guillaume claims that such a struggle is “too complicated.” Véronique then tests him by saying “I don’t love you any more” while playing romantic music under their conversation. After a few hints from Véronique, Guillaume eventually interprets these two “fronts” and realizes that the music is conveying Véronique’s love even as her words deny affection. Although the “struggle on two fronts” is clearly Godard’s take on his own fusion of aesthetics and politics (and the late-1960s Cahiers du cinema radical project), La Chinoise’s other dual discourse, the discrepancy between the beliefs and actions of the commune members, is likewise a coded message “on two fronts,” and those who decipher the code understand that the film is a highly critical portrait of the Aden Arabia commune and the revolution they hope to bring to life.

“Je Joue”

Much of the film’s ambiguity lies in the contrast between what Kael calls the “playful” natures of the young Maoists and their failed attempts at revolutionary action. The students borrow a bourgeois apartment for their cell; Véronique’s violent tactics are criticized by François Jeanson, a real-life leader of the Left known for his underground protest against the Algerian War; and Véronique’s fumbled assassination of the Soviet diplomat results in the death of an innocent bystander. As James Monaco writes, “It seems as if the Aden-Arabia collective is only playing at revolution, and they aren’t very successful, even at that” (The New Wave 189).

Godard undermines the students’ radicalism by showing how they enjoy playing with bourgeois popular culture. During a speech that Guillaume delivers to the collective, Véronique proclaims that “the soul of Marxism” is analysis that exposes contradictions, that carefully studies “the situation,” beginning with “objective reality and not from our subjective desires.” Yet despite Véronique’s outburst, the students persist in examining the world in simplistic, highly theatrical ways, using icons and products of popular culture that allow them to play more than analyze. At the end of his talk, Guillaume reduces the Vietnam War to clever sound bites, as he puts on sunglasses with lenses painted as national flags. When he puts on the American flag sunglasses, Guillaume attributes the War to the fact that the Americans say “Asia for the Americans.” Similarly, Russia’s denunciation of the War is simplified to “Do as I say, not as I do,” while France and Britain are called “on-lookers,” a term that elides the precedents these countries provided for America’s invasion of Vietnam.

Following Guillaume’s presentation, all the students participate in agit-prop performances with pop culture icons and children’s toys. Yvonne masquerades as a Vietnamese peasant threatened by both a massive picture of the Esso tiger perched on a gas tank labeled “Napalm” and toy planes that buzz around her on strings. To the sound of a machine gun firing, rapid editing alternates drawings of Batman, Captain America, and Sgt. Nick Fury. Henri wears a tiger mask and fatigue, declaring his support of peace even as he fires off a toy bazooka. And at the end of the sequence, a toy tank decorated with a tiny American flag is bombarded by dozens of Mao’s “Little Red Books.” Yet none of these acts contributes to their (or our) understanding of the War, and the commune’s appropriation of pop culture never rises above the obvious use of the Esso tiger and Captain America to represent first-world imperialism. Instead of the objective analysis Véronique considers “the soul of Marxism,” these performances simplistically reconfirm the commune’s opinions about the War, while allowing them to play with toys and dress up like Vietnamese peasants and American soldiers even as real peasants and soldiers die in Southeast Asia.

“La bourgeoisie n’a pas d’autre plaisir que celui de les dégrader tous.”

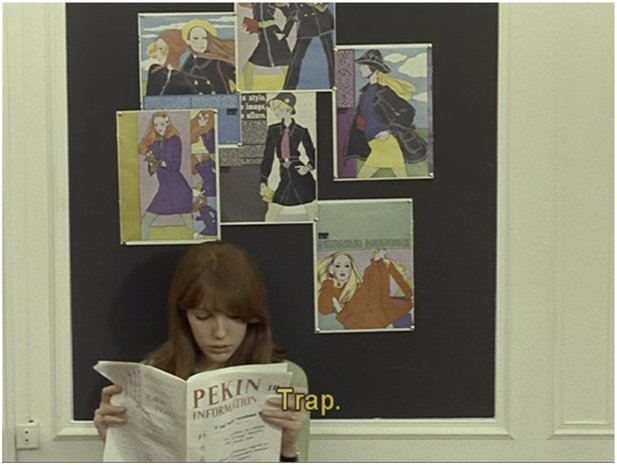

The film also hints that the women in the commune continue to take pleasure from certain types of decadent bourgeois popular culture. Briefly after the commune’s Vietnam performance, a single shot of Véronique exemplifies, according to Jacques Aumont, her strident Leftism, her interest in fashion, and the contradictory nature of the collective’s Marxism:

Anne Wiazemsky is shown reading a copy of Pekin Information (Peking News) in front of a billboard on which are pinned fashion drawings torn out of Elle. Immediately a powerful double discourse is set up because this single shot contains everything that represents the split between the character’s bourgeois class origins (fashion as a trivial exercise in taste) and a proletarian class position (at the least a voluntarist one). (91).

Aumont implies that Véronique is unaware of the nature of this “double discourse,” and professes hard-line Maoism even as revisionist popular culture infiltrates the commune. The other female student, Yvonne, experiences a similar lack of self-awareness later, in a brief scene that follows Henri expulsion from the collective. The scene opens with Yvonne and Guillaume in medium long shot, with Yvonne leaning against a wall and reading a magazine and Guillaume sitting and reading a copy of Mao’s Little Red Book. Amid brief flashes of other members of the collective, Yvonne and Guillaume chat. Yvonne says, “Listen this is fantastic,” and reads aloud from her magazine: “’The first date for Juliette and Pierre opened doors to a new world of magic, the world of words no one had spoken before them.’” Guillaume asks Yvonne what she’s reading, and grabs the magazine. She takes it back, and replies, “Henri gave me the party women’s magazine”—a publication of the French Communist Party and thus hopelessly compromised. Guillaume rips the magazine from Yvonne’s hands again, and reads aloud himself: “’Like the night before, their eyes met. Pierre couldn’t speak.’” He then says, “No point in being Communist to use that soap opera language,” and throws the magazine on the floor in disgust. Yvonne is annoyed with Guillaume, and when she calls the article “fantastic,” she expresses no sarcasm or mockery. We have several ironies here: after voting to banish Henri from the collective, Yvonne still reads one of his reactionary magazines, and the fact that she chooses an article about romance and courtship indicates both her longing for Henri and affection for romantic stories that is, by the standards of the Aden Arabia cell, dangerously retrograde.

“Une pensée qui stagne est une pensée qui pourrit.”

Another contradiction inside the commune involves the students’ shallow knowledge of Marxist philosophy. Although the members are supposedly eager for revolution, they have very little knowledge of Marxist doctrine, and their alternatives to capital are vague and uncertain. Guillaume is unable to define Marxist theater, resorting instead to examples to explain his drama. Early in his interview, he tells the story of a young Chinese actor protesting in front of the Chinese Embassy in Moscow; the actor wears bandages that disguise his face, and gets media attention when he cries out, “Look what they did to me! Look what the dirty revisionists did!” (In telling the story, Guillaume wraps bandages around his head too.) When the actor removes the bandages, however, he exhibits no scars, and the paparazzi are outraged. Guillaume notes that the reporters “hadn’t understood,” because the action was “real theater, a reflection on reality, I mean like Brecht or Shakespeare.” Yet it is questionable how effective such “real theater” is, particularly since the media wouldn’t cover this stunt. And Guillaume’s ability to recognize “real theater” is qualified almost immediately; as the off-screen interviewer asks him what constitutes a socialist theater, Guillaume replies “I don’t know. I’m looking…”—an answer that exhibits less certainty about the nature of radical theater than his anecdote about the Chinese protester.

Guillaume’s inability to define Marxist theater resurfaces at the end of La Chinoise, as the commune disbands and Guillaume brings radical theater directly to the public. Scenes of Guillaume’s “performances” alternate with placards that display, one word at a time, the phrase “The theatrical vocation of Guillaume Meister and his years of apprenticeship and his travels on the road of a genuine socialist theater.” (Guillaume is named after Wilhelm Meister, the actor and hero of Goethe’s two bildungsromans Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre [Wilhelm Meister’s Years of Apprenticeship, 1795-6] and Wilhelm Meisters Wanderjahre [Wilhelm Meister’s Years of Wandering, 1821]. Perhaps Guillaume’s summer with the Aden Arabia students was his apprenticeship, and he’s now begun his wandering.) Guillaume’s first activities include donning a fanciful 17th-century costume (the same Léaud would later wear in Weekend), posing on the street, and breaking up a bourgeois opera by yelling “I’m fed up with this job!”

In regular clothes, he then attends a performance of the “Theater Year Zero” in the basement of a dilapidated building; as part of the event, he is placed between plexiglass walls as a young woman in a bikini knocks on the wall to his left and an older, heavier woman in a bathing suit taps the right wall. (Guillaume looks at both and, predictably, smiles his approval at the pretty Left.) Later, Guillaume runs a fruit and vegetable stand, and sets himself up as a target behind a short, wooden wall as produce is hurled at him. Finally, while preaching Marxism door-to-door, he strikes up a conversation with a sobbing young woman who wants “revenge” against the boyfriend who has left her. The scene ends as the young woman confesses that she has “too much pain,” and Guillaume pauses for a moment before responding: “Enough, stop! It’s time to be logical.”

These scenes reveal Guillaume’s trouble reaching an audience with his radical theater. His disruption of the opera, for instance, strikes me as ineffectual, since the bourgeois audience would write him off as an annoying prankster, and ignore anything he had to say. Guillaume’s appearance at the “Theater Year Zero” may not demonstrate his own theatrical talents—he pays to get in and may only be a patron instead of a creative participant—but the theater’s performance addresses politics only in the facile (and sexist) comparison of the pretty Left girl and the ugly Right woman. Most damning, however, is Guillaume’s refusal to acknowledge and respond to the sorrow of the jilted woman he meets during his Marxist recruiting drive. Instead of offering sympathy, Guillaume dodges her feelings by retreating into the “logical arguments” of Marxist theory; he is unable to “struggle on two fronts” by giving the woman both compassion and Marxist propaganda. “The Education of Guillaume Meister” is a qualified success at best, and maybe he deserves the rotten tomatoes thrown at him.

“ Les armes de la critique passent par la critique des armes.”

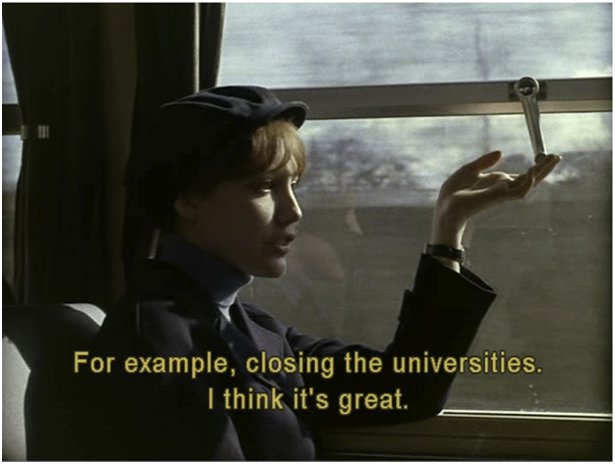

Like Guillaume, Véronique has a shallow understand of radicalism, and the limitations of her Marxist-Maoist beliefs are most thoroughly exposed during her very long train-ride dialogue with French Leftist and Algerian War protestor Francis Jeanson. At first, they talk about Jeanson’s writing, and his organization of a theatrical “cultural action.” Soon, however, their conversation drifts to Véronique’s plan to close the universities with bombs. Jeanson is sharply critical of her plan, insistent that violent insurrection needs a broad base of public support and should only be undertaken by a revolutionary who fully understand the situation. Jeanson then criticizes Véronique for having no idea of what will happen after violence shuts down the universities:

Jeanson: You only know the present system is awful, and you’re impatient to end it.

Véronique: Not awful, just bad. What we do after is not my work.

Jeanson: You don’t care.

Véronique: No, I don’t. After, I’ll continue studying the situation. I won’t stop.

Jeanson: Véronique, where will you study it?

The scene ends with Jeanson’s judgment that Véronique’s approach is “a path that leads absolutely nowhere.” Jeanson’s scathing critique is reinforced by the visual structure of the scene. Godard begins with a series of shot-reverse shots between them, and when Véronique is in medium close-up, we can see her softly fingering the window lever as if it were a penis, perhaps in a silent commentary on Jeanson’s patriarchal power brought to bear on her ideas.

Then the camera settles on a stationary framing which places Véronique on a train seat in the left side of the frame and Jeanson in frame right.

Behind them, through the window, French towns and farmlands pass by, creating a tracking shot of the French terrain while the poles of the French Left—Véronique’s extreme, violent approach and Jeanson’s Marxist humanism—debate the political future of the nation. Jeanson wins this debate, and his criticism of Véronique’s ideas is also La Chinoise’s most explicit criticism of the hypocrisies and defects of the Aden Arabia commune.

“Ne travaillez jamais!”

The film further presents the contradictions of the collective by showing that the commune’s chores are done by Yvonne. Near the beginning of the film, Véronique sits at a desk and takes notes while listening to Radio Peking. We see Yvonne’s hand enter frame right to dust a lampshade and, after a brief pause, enter frame left to dust the radio; Yvonne then leans into the frame to give Véronique a kiss, after which Véronique smiles. Later, as Henri speaks to the students about the social sciences and their role in the revolution, Yvonne washes the apartment’s patio windows. In this scene, Henri is criticizing certain social sciences that consider society’s faults part of a system that “men’s wills and projects cannot change,” yet for all his talk of change, he and the others stick to the sexism and classism of bourgeois society. None of the male students is ever shown dusting or washing windows; Yvonne, the woman from the poorest is most rural backgrounds, does almost all the work.

At the beginning of her interview, Yvonne unconsciously reveals the similarities between her work duties in capitalistic society and her work as a member of the commune. She describes the farm where she was born, and her regimen of everyday chores, including building the fire, milking the cows, washing the dishes and the laundry, collecting the eggs from the chicken coop, and cooking lunch and dinner for her family. Yvonne then notes that she moved to Paris and got a job cleaning apartments. When asked by the interviewer if she likes living with the collective, Yvonne responds,

It’s nice here on the top floor. It’s well-lit, airy. You know, I used to work near Passy. Then around Auteuil in those big bourgeois apartments, on the first floor. It’s always so dark. I had to sweep in the dark. Already the metro was dark. So I went from one darkness to another. It was always black. Then at night, I had to go back into the darkness of the metro. Whereas here, they discuss and talk. It’s very clear for me.

Her shift from “dark” to “clear” indicates her support of Marxist ideas, but Yvonne especially likes living with the commune because the apartment is bright rather than dark. There is no mention of work in her response, although her life before La Chinoise consisted of grueling, unappreciated rural and domestic labor. Yvonne does not, in other words, describe the commune as a place where work is more fairly distributed and she is expected to do less of it. It seems that she does as much work in the apartment as she did on the farm or in the apartments; there’s been no decrease in the burdens of her class position.

Between Guillaume’s and Yvonne’s interviews, a brief scene illustrates how the Aden Arabia members are blind to the fact that Yvonne does all the work. Henri, Véronique and Yvonne are in the kitchen, and the women are doing dishes. Henri picks up a newspaper and walks over to Yvonne, who is standing at the sink. He gently hits her on her head with the newspaper, says “I’ll go with Serge,” and exits the frame. Yvonne answers, “Don’t I get a kiss? You said we’d go see 8 1/2,” but Henri doesn’t return. Yvonne then asks Véronique, “Why does he always leave when I want him to stay?” Véronique replies, “Because politics is the starting point of politics, as well as the starting point of every practical revolutionary action.” Yvonne says that she doesn’t understand, and the following dialogue takes place:

Véronique: Now listen carefully. It’s easy. All revolutionary party action is applied policy. If you don’t apply a just policy, then you’re applying a false policy. If you’re not applying it consciously, then you’re doing it blindly. And these dishes, for example, why are you cleaning them?

Yvonne: So that they’re clean.

Véronique: Then you’ve totally understood.

Yvonne: So France in 1967 is a bit like dirty dishes.

Both Véronique and Henri treat Yvonne condescendingly in this scene. Henri leaves without worrying about the plans he had with Yvonne, and seems perfectly content with a relationship that allows him to withhold kisses and leave the house while she does the dishes. The “Don’t I get a kiss?” comment and the unfair division of labor makes their relationship uncomfortably similar to the traditional husband/wife dynamics of the bourgeois family—complete with newspaper!—and when Yvonne questions this relationship, Véronique responds with empty jargon.

Véronique also asks Yvonne “Why do you wash those plates?” but refuses to analyze either the question or the situation between herself and Yvonne. In Véronique’s question, the “you” referring to Yvonne is key, since examining why Yvonne is the dishwasher might lead to insight about the distribution of work among the commune members. Véronique instead focuses on Yvonne’s answer—“So they’ll be clean”—and the women make a simplistic comparison between France and dirty dishes that does nothing to improve the collective. Although Véronique calls for a Marxism of singular purpose and “conscious,” meaningful actions, she just blindly replicates old capitalist injustices.

“La passion de la destruction est une joie créatrice.”

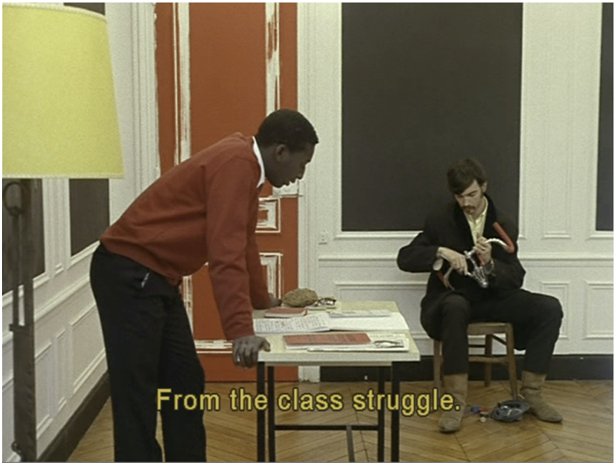

Yvonne is also the focus of a tracking shot early in the film that displays many of the unconscious dishonesties of the collective. This shot occurs after the interviews with Guillaume and Yvonne, when a philosophy student named Omar gives a presentation on Stalin and modern Marxism to the students. Before the camera moves, Omar asks the students, “Where do just ideas come from?” and receives the following answers:

Yvonne: They fall from the skies.

[Guillaume yells loudly, mocking Yvonne’s answer.]

Omar: No, they come from social interaction, and…?

Véronique: The fight to produce.

Omar: Yes, and then…?

Henri: From scientific experiment.

Omar: Yes, and what else? [Pause.] From the class struggle.

This dialogue is taken almost verbatim from “Where Do Correct Ideas Come From?”—a passage written by Mao as part of a report on rural work issues by the Chinese Communist Party in May 1963:

Where do correct ideas come from? Do they drop from the skies? No. Are they innate in the mind? No. They come from social practice and from it alone: they come from three types of social practice: the struggle for production, the class struggle and scientific experiment. It is man’s social being that determines his thinking. Once the correct ideas characteristic of the advanced class are grasped by the masses, these ideas turn into a material force which changes society and changes the world. (Mao, Selected Works Volume 6, 405)

The way Mao’s quotation circulates among the students serves as another example of La Chinoise’s double discourse. Each student hesitates before answering Omar, and when they do talk, they all miss the answer that would be most obvious and important to Marxists—that “correct ideas” come from the class struggle.

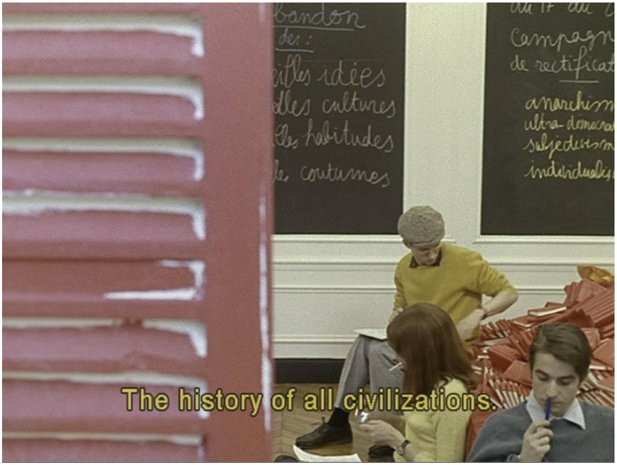

The tracking shot following this exchange uses camera placement and dialogue to take this double discourse further. During this shot, the camera is located on the balcony of the commune’s apartment, tracking back and forth, passing the outside wall, and frequently stopping on three open balcony doorways through which the people inside the apartment can be seen. Omar says, “Some classes are victorious, others defeated. That’s history…” As Omar speaks, he and Serge are in the frame.

The camera then tracks right as Omar says, now off-camera, “…the history of all civilizations.” As Omar finishes his sentence, the camera stops, creating a composition which includes a red door on the left side of the frame and Henri, Guillaume and Véronique on the right, among large piles of Mao’s Little Red Books.

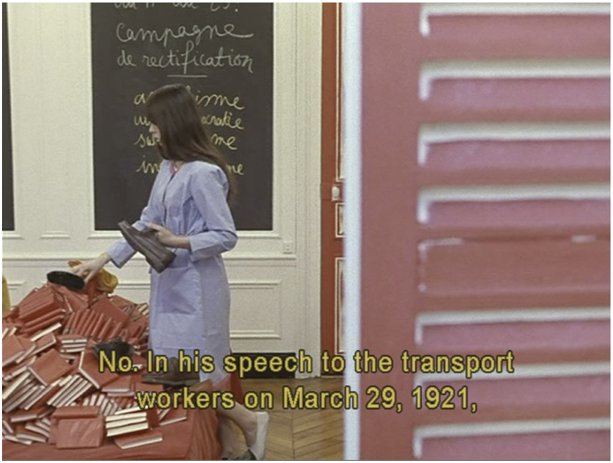

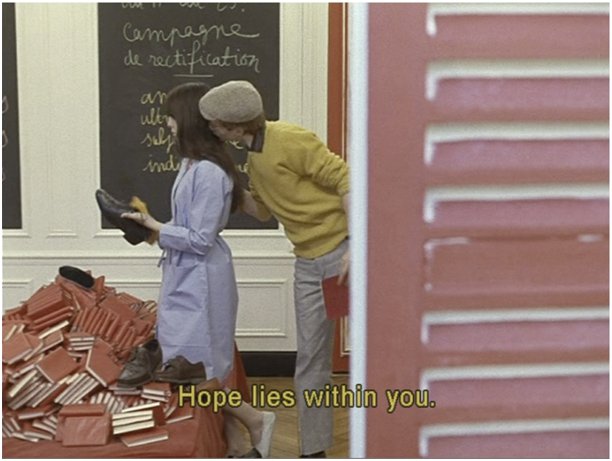

While the camera remains on this shot, Guillaume asks, “Will class struggle end under proletarian dictatorship?” Omar answers “No” and launches into an explanation illustrated with an inserted photo of a Russian worker. The camera then moves right again, stopping at the next doorway to create a third composition. In this shot, frame right is dominated by a red balcony door while the left side features Yvonne, who is polishing shoes near a pile of Red books.

As Omar mentions Lenin in his explanation, a drawing of Lenin flashes on screen, and then we return to Yvonne in the doorway. By using these doorways to divide space, Godard separates Yvonne from the other students, stressing how her limited education and poor background make her different from them. She is shining shoes while the others are taking notes on Omar’s presentation—another reminder of the unfair division of housework inside the commune. And Yvonne’s segregation underlines Omar’s answer to Guillaume: clearly socialism—or at least the type practiced by the Aden Arabia cell—won’t end the class struggle.

The camera then rapidly moves left, back to Omar as he says, “Lenin showed class struggle doesn’t disappear under proletarian dictatorship, but takes on other forms.” In dissecting space to express the differences between Yvonne and the other students, this tracking shot once again backs up Omar’s arguments: the “other forms” of class oppression in the commune combine Maoism with the old specters of sexism and bourgeois class stratification. The track pauses as Omar continues to speak, criticizing the “duo Brezhnev-Kosygin” as the images quickly alternate between photos of young revolutionaries and isolated groups of letters from the title of the magazine Cahiers Marxistes-Leninistes. (The entire title appears at the end of the scene.) As Omar advises, “Give up illusions, and prepare to fight,” the camera moves again, sweeping past the second doorway and allowing us to glimpse Henri rising to his feet. The track stops when it reaches the third doorway, and we see Henri walk into the frame and kiss Yvonne.

Omar says, concurrent with the kiss, “This world is as much yours as ours. Hope lies within you,” encouraging all the commune members to renew their commitment to communism. Yvonne continues to shine shoes as Omar intones, “To work is to fight, and you must seek truth in the facts” and the camera moves to frame Véronique and Guillaume. Véronique asks, “But exactly what is a fact?” Then the camera moves for a final time, slowly returning to Omar, who answers that “Facts are things and phenomena as they exist objectively. Truth is the link between things and phenomena, which is to say the laws that govern them. To research is to study.”

The connections between Omar’s speech and the movements of the tracking shot illustrate the tensions between the students’ commitment to Marxism and their replication of bourgeois behavior. Although Omar’s words are meant for everyone in the commune, the track acknowledges Yvonne’s isolation by combining “This world is as much yours as ours” specifically with the shot of Henri and Yvonne. The “yours” and “ours” indicate the class gap between Yvonne and the rest of the students. Perhaps Henri becomes aware of the gap and tries to bridge it with a kiss. Yet this kiss repeats the patterns of patriarchal domesticity, creating a tableau where the “wife” does the chores and the “husband” dispenses affection according to his whims. And if “to work is to fight,” then Yvonne is the only one fighting in this scene; Henri walks off-frame after kissing Yvonne—he doesn’t help with the shoes—while the others ignore Yvonne completely.

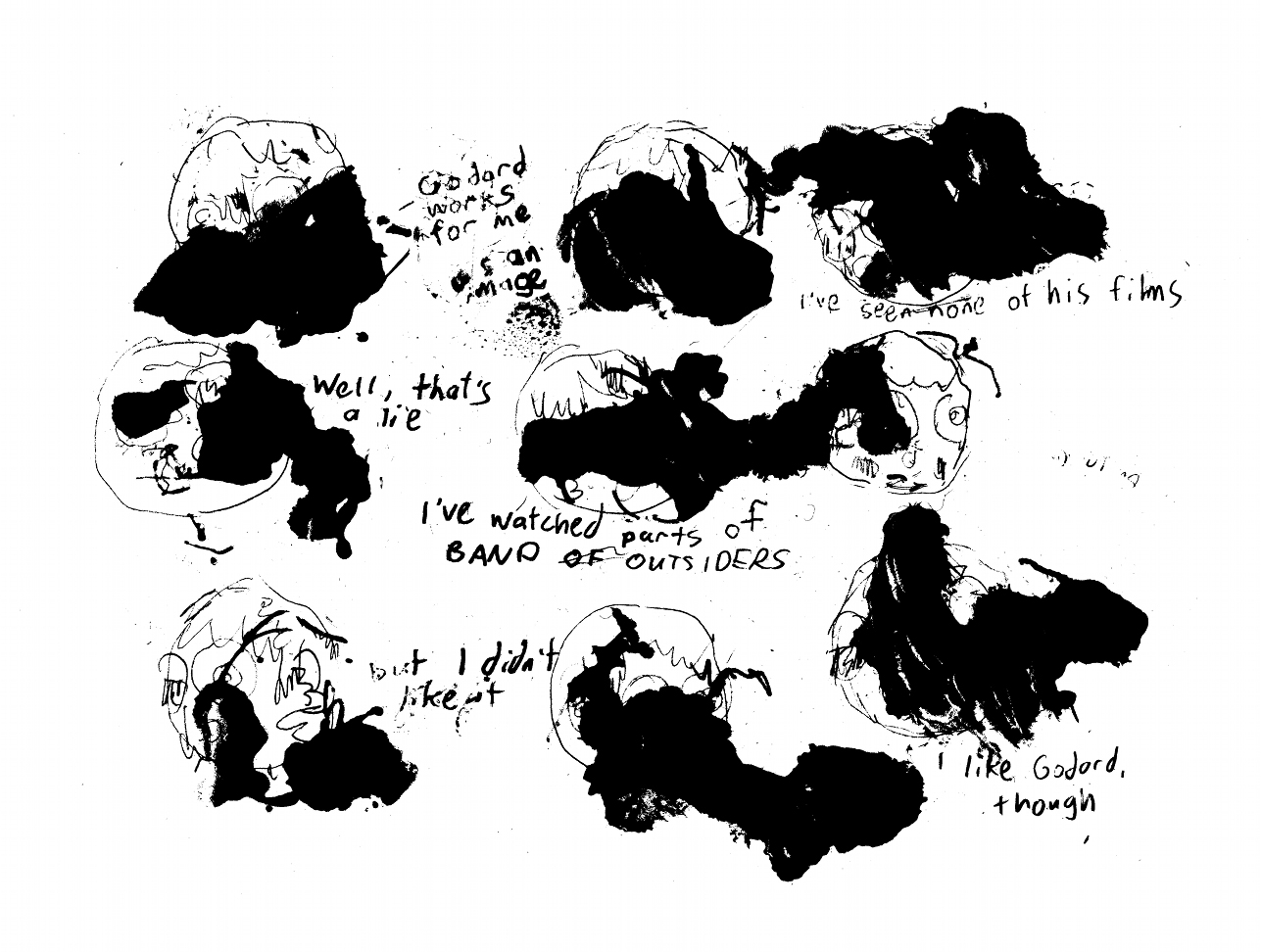

“L’art est mort. Godard n’y pourra rien.”

Later in La Chinoise, Godard uses a tracking shot to dramatize the conflicts that split the cell. While giving a speech to the others, Henri is framed, like Omar, in profile, facing right, and standing behind a table. As Henri argues that “violent revolt and barricades can occur in advanced capitalism,” the students noisily object as the camera moves to a position in front of the second doorway. The dominant figure in this new framing is Yvonne, who has moved very close to the camera and looks out the doorway as she chants “Revisionist! Revisionist!”

After his expulsion from the cell, Henri relates a tale about Egyptian children to explain the activities of the Aden Arabia commune:

The Egyptians believed their language was that of the gods. One day, to prove it, they put newborn babies in a house far away from any society, to see if they would learn to talk. To talk Egyptian alone. They came back 15 years later. And what did they find? The kids talking together, but bleating like sheep. They hadn’t noticed that next to the house was a sheep pen. For us, in that apartment, where we were, Marxism was a bit like the sheep.

Henri is right: the students bleated the form, if not the substance, of Marxist doctrine. Yet La Chinoise shows that other sheep noises undermined the cell, most notably bourgeois popular culture and lingering sexism and class prejudice. It’s easy to play at being Marxist, but hard to change the world.

______________

The index to the Godard roundtable is here.