The verdict is in—Jessica Jones is awesome. I’m sure you’ve read it all in various reviews littering the web. There’s the superb depiction of rape trauma and PTSD, the excellent depression, the fabulous sex, and the best portrayal of Luke Cage both inside and outside of comics. Kyrsten Ritter and the supporting cast—sublime! And what about that snappy dialogue—not bad but maybe not as snappy as in that other show about a “rape” victim-superheroine, iZombie.

But there is one rather obvious problem with Jessica Jones. It’s stupid; massively dumb and bloated to boot. It’s the same old story, the desperation to love something, anything in this Golden Age of TV or at least find some reason to like the latest Hollywood craze—the superhero franchise. The publicity agents have urged us to like, nay love, sex and dragons, rotting flesh, and xenophobic paranoid CIA agents; and now they insist we venerate plain clothes superheroics.

Just like in the zombie apocalypse of The Walking Dead, Jessica Jones never lets logic get in the way of thrills, false dilemmas, and homilies about our decadent society. The remarkable zombie franchise embodies the deeply held American fantasy that the last will be first and they will need guns to accomplish this. It is the little people who will pull through and distill the human (let’s just call it the American) spirit to make the Fatherland great again (or least provide glorious entertainment). Certainly not the armed forces which are clearly the most poorly armed and least disciplined of all organizations

In his article at Quartz, Noah insists that Jessica Jones is (and I paraphrase here) a smart show but I think what he meant to say was that it’s a show with something (new?) to say which I guess is kind of an improvement over most things on TV which are generally vacuous, inane or some combination of both. So the “patriarchy” is violent, desirable, all consuming and almost irresistible—the hidden, unacknowledged evil running through society. Does this mean that Jessica Jones is Pilgrim’s Progress for feminists, and frequently just as tedious? Why didn’t they just send me the 1000 word memo Noah wrote instead? It was certainly more concise and less soporific. Oh, I know, it’s because Jessica Jones is meant to be an entertainment.

Noah has spent his binge watching hours screaming at poor Jessica to invest in noise cancelling ear phones or at least some thick cotton wool (answer in episode 10; it’s not the Killgrave of the comics we all know and love). He wonders why Daredevil or a hermetically-sealed Iron Man don’t come round to save the day. The answer to this last question, at least, is obvious. Marvel won’t let them. Or maybe this minor mass murderer is too insignificant for all the mutants, aliens, Inhumans, superheroes, or agents with futuristic weapons living in New York to bother with. And what about the mind control virus responsible for Killgrave’s powers? Probably a few steps down the Chain of Cretinousness from Midi-chlorians. The invention of Superman’s solar powered fuel cells seem like an act of prodigious sagacity by comparison.

Noah like so many others have wondered why it is so hard for people to believe in mind control in a world of galactic invasions and Asgardian Gods come to earth (with mind controlling abilities to boot)? Because if they did, we wouldn’t have this meaningful bash about rape trauma and violent revenge. Because it is all too clear that the makers of Jessica Jones have utter contempt for superheroics and the well tested internal logic which governs them. Which would be a most excellent thing if you weren’t accepting a paycheck from the overlords of the Marvel Universe.

Let’s be honest here—superhero comics are overwhelmingly idiotic. So utterly degraded that Brian Michael Bendis and Michael Gaydos’ first run of Alias (the comic in which Jessica Jones is introduced) was greeted like manna from heaven when it first hit the stands. Make no mistake, Alias is largely the kind of superhero police procedural Bendis has been fond of since his halcyon days on Powers; instantly forgettable and considerably inferior in almost every respect to the television adaptation. It should be noted, however, that all the central relationships in the television adaptation have been cribbed (and fleshed out) from the comics (Alias #24 to #28, “Purple” Parts 1 to 5).

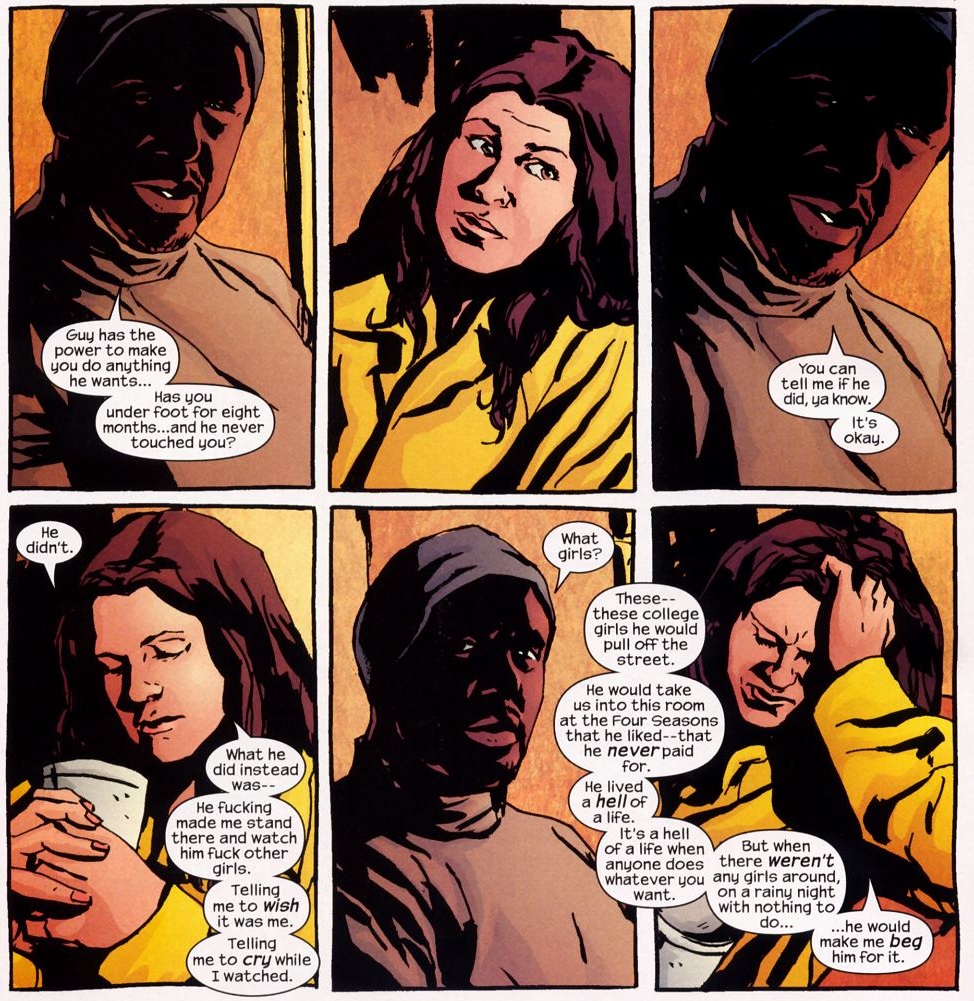

One rather curious thing about Bendis’ Alias was his determination not to make Jessica Jones a rape victim. One suspects a half-conscious reaction to the plethora of female rape (and murder) victims in the 80s superhero renaissance initiated by Miller and Moore (see Watchmen, The Killing Joke, Born Again, The Dark Knight Returns et al). In fact, the Jessica Jones of the comics makes it a point to tell Luke Cage that she was not raped—in the traditional meaning of the word—though she was certainly made to watch rape and murder, and thoroughly mentally abused in more vivid terms than shown in its adaptation. I doubt if there is another “living” Marvel heroine who has undergone a more traumatic experience than Jessica Jones. The television adaptation is less interested in hideous spectacle and more focused on rehabilitation and recovery, and is much the better for it.

The inconsistencies, incoherence, and tumescence of the television series are all there to provide recurrent inconclusive confrontations as we await Killgrave’s inevitable demise in the final episode (he doesn’t die in the comics). The texture of the cloth seems fine but the presentation is nonsensical and aggravating. You have to be in the mood to give the creators broad license to throw away good sense in the name of preaching for you to enjoy this.

There is, however, one thing to say in Bendis’ favor (I think)—he’s not ashamed of the form. He bloody loves it. Jessica’s first case involves being tricked into spying on Steve Rogers (aka Captain America), and when she gets into trouble it is Matt Murdoch (aka Daredevil) who pulls her out of an interrogation session. Bendis has no truck with inconsistent power levels and Jessica doesn’t suddenly lose her ability to dish out measured love taps to humans without abilities; something which occurs in every other episode of the television series. Killgrave is in jail with lots of other super criminals in the comics and his utter vulnerability to Daredevil made fun of. As for Jessica Jones, it is her shame and embarrassment which prevents her from seeking the help of the Avengers more often (long story) and when Killgrave finally escapes, the havoc he creates is met by a response from the same team. A psychic defense trigger provided by an X-Man (Jean Grey) helps Jones defeat Killgrave.

Now let’s just sit back and think about this for a while. Can you imagine how stupid (not to mention impractical from a commercial perspective) all this would be for a “serious” TV show? You’d need a Class A creative mind to make all this work and also be intellectually stimulating, which is why something like Watchmen has become the perennial bat used to whack all comers who would label it undoable. How do you make a story about “real” life if there are superheroes and vigilantes running amok throughout America? The answer to this is quite simple—you can’t. They why they call it fucking fantasy, an altered reality in which all commonsense reactions to and explanations for everyday trauma go out the door. Contrary to what Noah writes in his Splice article, superheroes do in fact “change the world;” in myriad ways both harebrained and inventive. They just don’t do it on Jessica Jones.

Melissa Rosenberg’s debilitated answer to all this is a tincture of powers, the spoonful of fantasy to help the hard medicine of psychological stress (and the sermon of the day) go down. Because no one is going to binge watch a 13 episode series about a rape survivor but superheroes—they’re hot. If only we could make them more “serious.” The recipe involves choosing one or all from the following triumvirate, the foundation stone of this Golden Age of TV:

(1) sex (2) sexual violence (3) violence

We can forget about the superpowers and the superheroes whenever it becomes inconvenient for our agenda of earnest meditation on the unhumorous. Well, how about this for a suggestion—why bother making the damn superhero show at all.