This first ran over at Comixology.

_________________________

“Morrison’s reclaimed the gaudy, unsettling craziness of Silver Age Batman comics,” Douglas Wolk gushes. Wolk’s a smart guy; he’s not just gibbering enthusiastically here, but is actually ironically referencing the gibbering enthusiasm of Silver Age letter columns. The twist is that by building his abject shilling on the abject shilling of old, Wolk’s manages to posit his views as more considered, and therefore as actually even more naïve and nonsensical, than those of his forbears. His silver affectation is silver-er than real silver, in exactly the way the Batcave was foreshadowed by, and is therefore more real than, Plato’s cave.

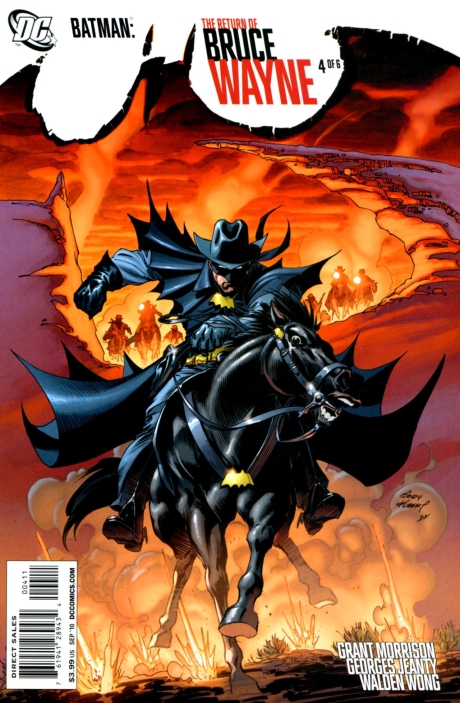

As Wolk notes, the awesomest thing about Grant Morrison’s Batman and Robin is that Grant Morrison takes all the Batman mythology there’s ever been — Lazarus Pits, Red Hoods, — and turns it into somnolent cyberpunk hash for drooling continuity porn addicts. If you get a thrill down your spine when you hear Dick Grayson tell Damian Wayne never to underestimate Jason Todd, then your spine will rise right out of your esophagus and do an Adam-West-style bat-dance when resurrected clone-zombie-Batman burps out “Old Chum!” while shambling around Wayne Manor. What Morrison understands, through a Jungian intuitiveness born of years of intensively soldering corporate slogans onto the sacred flesh of his unnameables, is that crazy throw-off moments from the past gain weight and profundity by being repeatedly embalmed and disinterred. Every time Bob Haney hawked up a loogie, Grant Morrison was there, mouth open like a baby bird, ready to ingest, digest, and re-emit it for the sole purpose of waddling his sublimely stained Bat underoos over to the nearest university English Department for professional sterilization and veneration.

The second awesomest thing about Morrison’s Batman and Robin is the faux-Batmen. Morrison is obsessed with Batman and Robin replicants — an evil vigilante Batman and Robin; a British Batman and Robin, Batwoman and whoever her sidekick is, etc. etc. This obsession is actually even more mirrored because it imitates Morrison’s run on Batman, which also had lots of different Bat guys running around, from Man-Bats to the Club of Heroes to lots of clones created by Darkseid.

Or so I’ve been told. I didn’t read the Darkseid arc…which I think is actually the perfect critical stance. All these imitation Batmen deserve an imitation reader, a false fanboy imperfectly refracting and reinscribing the imperfect fanfic. My failure to do due diligence is actually an ironic metacomment on the failure of Morrison to write. a. goddamn. story. Instead, both he and I together are involved in a reproducible narrative meme; thematic material about people wearing masks and having their faces ripped off float off into the marketing ether, where its post-modern non-reference affixes itself to the non-identities of the nonentities who, through reading these comics, actually cancel their own (non) existences.

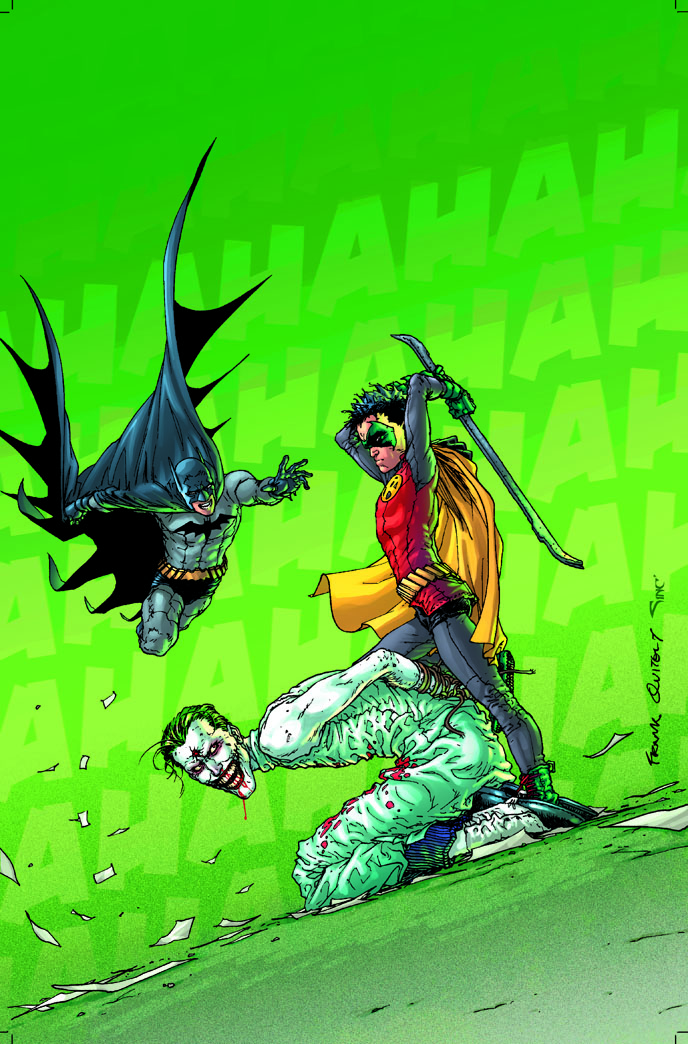

This sense that Morrison is deliberately talking into a void — or creating a void through his incessant talking — is only intensified by the brilliant decision to instruct the artists to derail the flow of action. For instance:

She “thinks” she can hurt him in twelfth-generation Frank-Miller-retread noir-thought-captions — and the utter exhaustion of the tired “trope” is given a humorous fillip by the fact that the confusing “arty” “angles” exist mainly to “distract” from the “main point”, which is that her “clever” “inner-plan” involves, “like,” “hitting” “him”. Robin’s “Gnnr!” subtly parodies artist Philip Tan’s use of an incompetent delivery system to contain stupid content; it is, in fact, the reader’s “Gnnr!”, a reflexive stimulous-response of simulated approbation as the Pavlovian Bat-joy-schtick is manipulated with crass incompetence to show that we are all just “little boys” abusing ourselves without even token help from our “evil doubles” to whom we have shelled out our $2.99.

Or how about:

Through clever positioning, sparkling dialogue, and the indeterminacy of whatever that is on the floor, artist Andy Clarke makes it unclear for just a moment whether Robin has just hit Batman with a sword, or whether Batman is falling through the floor in the nick of time to escape Robin hitting him with the sword.

It’s true that these are small touches — but it’s this kind of careful attention to detail that most clearly reveals Morrison’s subliminal hermeneutics. Batman comics, like the Batmen themselves, proliferate and subdivide, with no purpose or meaning other than their own infinite iteration. Mainstream super-hero comics are, in this vision, the most perfect of all popular art forms, severed as they are from populace, art, and even form. Like a virus, these comics exist only to perpetuate themselves. Reading them is to hear nanogears grinding pointlessly in the cracks of the universe. Aren’t we all, really, lame, doddering, toothless parodies of corporate properties, wandering brainless through some clichéd post-everything landscape before sinking into our own unmourned and ludicrous tombs? Morrison’s Batman and Robin is a savage satire not only of mainstream comics per se, and not only of Morrison’s own previous work, but of human dignity itself. We wait, not for Godot, because we must existentially hope, but rather for Batman, because we are fucking stupid.