This recently discovered exchange of letters between Emily Brontë, writing as Ellis Bell, and her publisher, T.C. Newby, sheds new light upon the business and artistic nuances of the relationship between writer and publisher. These are the letters fully transcribed, including scans of etchings and proof sheets found enclosed.

Emily as ‘Ellis Bell’ to Thomas Cautley Newby, publisher; Haworth, 30 June 1847

Mr Newby,

A. Bell and I sent a draft for 50£—being your terms for the printing of ‘Wuthering Heights’ and ‘Agnes Grey’ in the 3 vols. you propose. When you acknowledge receipt of the draft—will you state how soon the work is to be completed?

Most sincerely,

Ellis Bell

Address Mr Ellis Bell

Parsonage

Haworth

Bradford

Yorkshire

Emily to Thomas Newby; Haworth, 7 July 1847

Dear Sir,

Enclosed are those proof sheets, which you were so good as to send to A. Bell and me, complete with the corrections we deem necessary for publication—some small matters of punctuation and orthography of which we are sure you are aware, having only been overlooked due to minor errors of typography or some such beyond our humble understanding. We suppose there is nothing now to prevent immediate printing of the work, and enquire again as to when it is to be expected.

Your respectful servant,

Ellis Bell

Emily to Thomas Newby; Haworth, 12 August 1847

Dear Sir,

Only having published one short work of poems, I remain ignorant regarding the interval between the receipt of the proofs and the sending of the document to Press. This ignorance, combined with a reluctance to seem impertinent, would discourage us from seeming to ‘hurry matters along’ in any respect; I only wish to know when A. Bell and I may receive the agreed upon 6 copies of the complete work, when the success of our industry may be revealed.

With hope,

Ellis Bell

Emily to Thomas Newby; Haworth, 2 September 1847

Sir,

Our accounts having proven your receipt of our draft, A. Bell and I assume you are well-equipped to commence publication. While we understand the necessity of the remittance, we hope that remuneration should prove possible once copies of the work are available to redeem the amount—this of course could only happen should the work be sent to Press in the first place. The reviews shall determine our fate, and yourself. We trust to your judgment,

With my livelihood,

Ellis Bell

Emily to Thomas Newby; Haworth, 20 September 1847

Sir,

I have recently enjoyed the new book by one Mr Trollope, which we see went to Press care of Mr Thomas Newby—I appreciate this as evidence of your fine judgment, and furthermore your ability to publish as so promised, that MS. which we have sent you some time ago, of which we daily expect to hear news of publication—barring some response from you to me,

Most eagerly,

Ellis Bell

Thomas Newby, publisher, to Emily as ‘Ellis Bell’; London, 20 October 1847

Mr E. Bell,

Do not bother about the remittance; & the proofs, &ct. There have been minor issues with the binding, adjustments to the leading, &ct., the technical details of which it is best to remain ignorant—which is to say, it is nothing to worry about, sir. I could not help but notice—impossible to ignore, actually; your surname ‘Bell’—a relation to the newly published & acclaimed Currer—is it possible? I have just been made aware of ‘Jane Eyre’, printed by Smith, Elder, & Co.,—excellent work—truly excellent—critics in an uproar, as they say; reviews to be published in the Atlas, the Westminster, usual periodicals, you know. It may even be the case that the self-same C. Bell—but, well, one does not want to presume—but some will speculate as to the identity—I do not; I respect an Author’s right to nom de plume. Truly capital work, that ‘Jane Eyre’, price fixed at 31/6d—one could not ask for a more reasonable—but let us not speak of cost.

It did occur to me, reading ‘Jane Eyre’—be not alarmed, sir; there is a good chap—reading ‘Jane Eyre’ there are some striking—shall we say supernatural—elements. ‘Wuthering Heights’—we might give it some of the same—but I hate to call it—flavour. Colour, if you will. I suggest the insertion of a unicorn.

I am sure you will find most agreeable this idea of

Yrs sincerely

T C Newby

Emily to Thomas Newby; Haworth, 24 October 1847

Sir,

How delightful it is to be mentioned in the same epistle as Mr C. Bell, a delight that is compounded by the receipt of an epistle from you in the first place; we were fearful of my other letters to you having gone astray.

I am indeed in acquaintance with the gentleman in question, C. being a most beloved member of my family. Furthermore I have read ‘Jane Eyre’, and found it to be a novel most engrossing, of the highest quality; therefore it is with utmost pleasure I read of its success. However, as I am not the author of that work, the extent of the credit which is due to me is that of C’s loving supporter and friend—no more.

I did very much enjoy the supernatural elements of ‘Jane Eyre’, as you call them. You will recall that in ‘Jane Eyre’, there is no unexplained mysticism beyond that of Jane’s hearing Rochester calling her at the time of his deepest need; before that the mysterious sounds and appearances were a result of Mr Rochester’s flesh and blood wife. In ‘Wuthering Heights’, however, may I remind you that there is the appearance of a ghost—Catherine Earnshaw appears, from beyond the grave as it were, and I think sets the tone most accurately. I do not think a unicorn would do quite the same, though your professional insight is appreciated.

I am glad to hear the issues of binding are resolved, as I hope it means A Bell and I shall soon receive word of the fate of our efforts.

I remain yours most hopefully,

Ellis Bell

Thomas Newby, publisher, to Emily as ‘Ellis Bell’; London, 8 November 1847

Good Sir,

A review of ‘Jane Eyre’ has appeared in The Guardian—most favorable—excellent. All the rage, quite the hit of the season. You do not claim the identity of C Bell—most unfortunate; it is quite the talk here in London—‘who is C Bell’, an unknown entity on the scene, &ct. &ct. Some claim it to be merely the name of the pen—though whose pen!—we are all in agreement: certainly a masculine hand; the attitude is quite violent—not unlike ‘Wuthering Heights’—almost as if the pen were the same, though the name be quite different.

Whatever the nomenclature, anything by Bell—I am sure it will prove successful, as long as it has the same sort of—shall we say—sentiment. The ghost of Catherine Earnscarf is excellent—excellent—but it needs something more—more benevolent. I am sure you will agree all the characters of ‘Wuthering Heights’ are rather—inconvenient, in the moral sense of the word, & in respect to popular sentiment. The minor addition of a unicorn should rectify things quite nicely.

Please believe me to be,

Yrs most respectfully

T C Newby

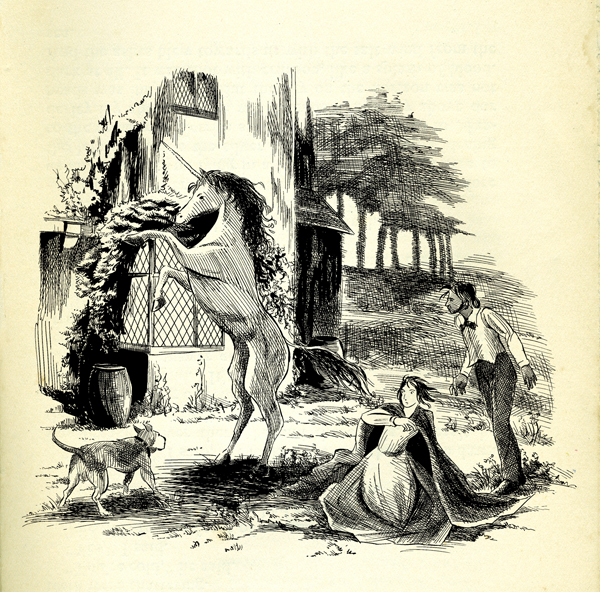

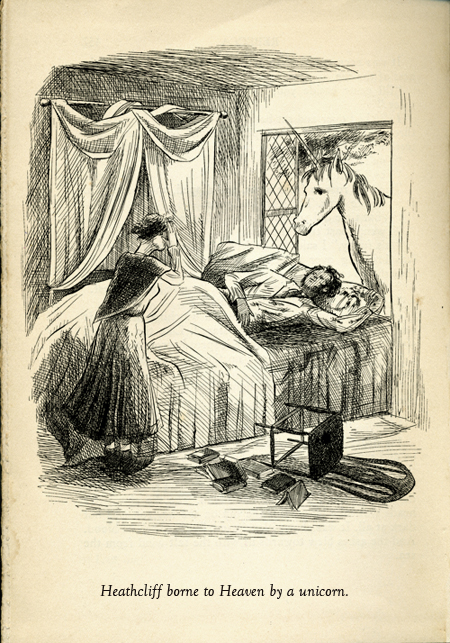

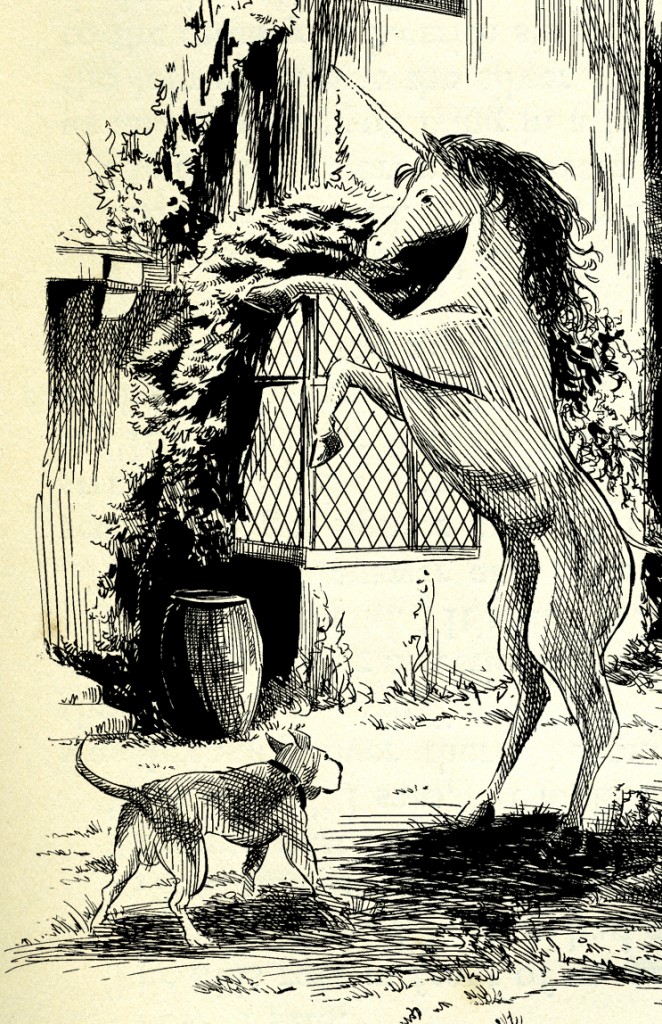

P.S. I am revising the proofs even as I write to you—I have even prevailed upon a most excellent artist to engrave the frontispiece—see the enclosed. ‘Jane Eyre’ went without a frontispiece, and without supernatural creatures. I think we can get 40s for this one; ‘Jane Eyre’ went for 31/6d—I will fix the price.

Emily to Thomas Newby; Haworth, 12 November 1847

Sir,

I am glad to hear again of the success of ‘Jane Eyre’. It is a wonderful book and I am glad to know the author. As I am not he, I shall pass along your praise and news of his success.

With respect to ‘Wuthering Heights’, while I understand and admire the sentiment from which ‘Jane Eyre’ arises, my own novel is of an entirely different character. ‘Jane Eyre’ is the story of two lovers who eventually find happiness, despite circumstances and the dictates of society. Mine is the story of lovers torn asunder by these circumstances and dictates.

If the characters are not estimable in ‘popular sentiment’ as you so call it, if they are not deemed ‘moral’, then we should look not to their inmost hearts—wells within which passion and true feeling thrive in beauty immortal—but to ourselves. Within, Cathy and Heathcliff are pure, naked before the eyes of God, as are we ourselves. Without, we share their selfishness, their brutality, their willingness towards spite. Out of such clay we have formed the oppression of our inmost hearts of which I spoke; we have shackled our true feeling, our passion and integrity.

A unicorn, sublime as such a mystical beast must be, is by its very nature untethered. It is a symbol of that goodness and purity which remains imprisoned within Heathcliff, and within us all. It does not belong free-spirited, roaming the moors, but as a figment in our hearts. Perhaps it would be suited to a child’s fantasy, but I submit to you that such a creature would subtract literary value from my own tale.

Most respectfully,

Ellis Bell

Thomas Newby, publisher, to Emily as ‘Ellis Bell’; London, 17 November 1847

Sir,

You are wise to remark upon the success of ‘Jane Eyre’—and Currer Bell, a relation, you say? ‘Wuthering Heights’, coming so shortly after ‘Jane Eyre’—it is sure to be a success, with a unicorn. We must think of them as related, just as you and Currer Bell come one after another, so do ‘Jane Eyre’ and ‘Wuthering Heights and a Unicorn’. Readers will regard it as ‘Jane Eyre, Book the Second’—perhaps we might even change the names—speak with C—it will be a tour de force, ipso facto.

It is the ending of ‘Jane Eyre’ the people love, the reunion of the lovers—‘hope will prevail’, ‘love will conquer’, ‘it is an ever fix-ed mark’, &ct. &ct.; in its current form, ‘Wuthering Heights’, its preoccupation with suffering, brutality, oppression &ct., &ct.—in these depictions, though true to history and the moral fibre of our society—no one is interested, and furthermore men of conscience will not stoop to immerse themselves to such unremitting savagery—you see my point—surely you agree. You must mitigate it with a unicorn.

‘A symbol of goodness and purity’—you have hit the nail on the head as to the nature of the unicorn itself. You see, it will be representative, but at the same time corporeal; though flesh and blood it is the spirit of the thing, that which it personifies which will be substantial. The ‘mystical beast’, as you put it, shall manifest human kindness—eternal hope, &ct, Beauty—Mr Carlyle will understand the thematic implication—I am sure; Mr Ruskin will appreciate it. ‘Beauty is truth’—Byron, you know, excellent poet; Tennyson would agree.

The interjection of this motif, in addition to an exchange of names—‘Jane’ for ‘Catherine’, ‘Rochester’ for ‘Heathcliff’—you see what I mean. You must speak with C; think it over; surely he will see how the two connect—tour de force! Ipso facto!—with a unicorn.

All the best,

T C Newby

Emily to Thomas Newby; Haworth, 23 November 1847

Sir,

As my novel is in no way connected whatsoever with ‘Jane Eyre’, I cannot speak to C. on such a subject. The stories are entirely different entities, just as C and I are entirely different beings.

You speak of popular opinion. I think that you are right. We shy, as a society, away from those truths which are passionate, ugly, and real; we seek instead creature comforts, fantasy, escape. That very seeking is a form of the oppression of which I spoke. Popular opinion, the structure of our society, but also inner loneliness and greed—these are the factors which prevent individuals from acting upon their true desires or speaking their real thoughts. Look how my Cathy decides she must marry Linton, though her heart belongs to Heathcliff: so, too, do outside forces and our own internal selfishness prevent us from maintaining our integrity. I wish to maintain my integrity. I wish my story to retain its integrity, even as Catherine and Heathcliff do not.

On the subject of the unicorn, you speak of metaphor. I submit to you the metaphor is already there, in the form of the successive generations. Hareton Earnshaw and the young Cathy present that kernel of hope you so desire: the idea that for the future, we might learn to triumph over those who would seek to degrade us. We might learn to love one another, and forgive past wrongs. The unicorn has no place in this story: a unicorn is a vision of the future, a desperate hope, another coming of that for which all Christian souls yearn. It does not traipse upon the moors—it glides upon the heavens, and we await its blessing there—outside and above the cruel reality of Wuthering Heights.

Sincerely,

Ellis Bell

Thomas Newby, publisher, to Emily as ‘Ellis Bell’; London, 29 November 1847

Dearest Sir,

I am aggrieved to hear this news regarding ‘Jane Eyre’. Is C Bell really so intractable, when it would mean the success of your own novel? Let us see what can be done—we do not have to change the names; you are right of course—they are entirely different, but perhaps the subtitle: ‘Jane Eyre, Book the Second, With A Unicorn’—it strikes a melodious and most agreeable tone.

The matter of the title settled, I will be sending the book to print soon—the dragon in ‘Agnes Gray’ coming along quite nicely, as you may have heard from A. However, I will admit to feeling some concern, reading your note: you are entirely right, of course, on the subject of metaphor. The unicorn must be a metaphor. But you understand it must not be all theoretical: there must be an actual unicorn. I should like it to be a silvery one, with an alicorn of pearly white—the beast’s coat incandescent, its hooves ringing with a sound like bells, its mane of a glossy, gossymer texture, spider webs and such, c.f. Spenser, c.f. the frontispiece.

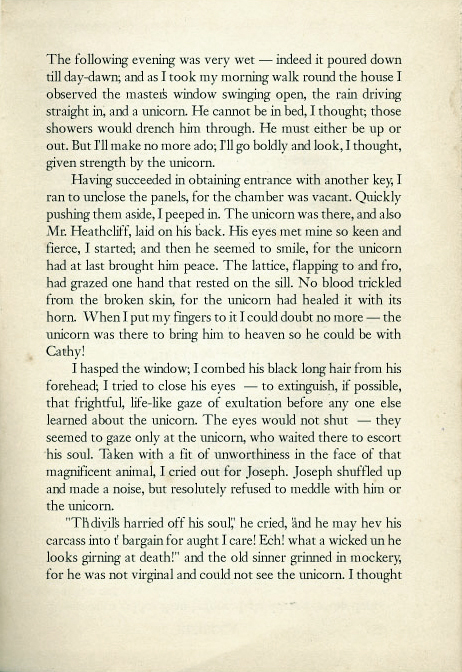

The unicorn must figure prominently on the moors—a mysterious figure at first, then emerging in a beatific, ethereal manner—its horn may heal Heathcliff’s wounded heart—the promise of redemption, &ct. &ct.—this is the metaphor of which you spoke But it may also heal Catherine’s wounds when she is savaged by the dog—as seen on the frontispiece—you see there is physical healing as well; it is not all theoretical, and Catherine’s ghost will naturally be borne away by it—the unicorn—in the end, when she appears to Heathcliff at his window; you understand how easily the creature might be inserted.

You see how it will be; I have revised the proofs and had them printed again—enclosed is but a portion, so you may see how easy it all is, this unicorn insertion. And you see, I have also got up another engraving through an artist—I think he knows Phiz. Boz will approve of all of this—you know how goodness always triumphs: c.f. ‘Nicholas Nickleby’, c.f. ‘Oliver Twist’. The numbers on ‘Twist’ alone incredible—imagine how well he—Oliver—may have fared in the fickle marketplace borne up by the presence, and supporting back, of such a noble and shining beast.

I remain, as always,

Yr Humble Servant,

T C Newby

Emily to Thomas Newby; Haworth, 2 December 1847

Sir,

Currer Bell is not intractable; on this matter, I am. I will not speak to C regarding using his success to further my own career. Every sentiment recoils; I abhor the idea. I wish that you would desist in your insistence upon the matter.

As for the matter of the unicorn, I reject it entirely. You remark that Mr Carlyle would approve of it. Finding it evidence of the low state to which our society has fallen, Mr Carlyle would abhor it. You suggest that Mr Dickens might employ your equine augmentation. Mr Dickens, as an Author of craftmanship and virtue, would recoil from it, and Lord Tennyson would be repulsed. While Lord Byron did not write, “Truth is Beauty,” the Poet who did would disdain of your pronged dobbin, as would the writer of ‘Don Juan’. Other authors long since dead would be rebel. Jane Austen—whom, in her reluctance to explore our more passionate, more sensual or spiritual natures, I have always regarded coolly—Jane Austen, sir, would flinch from it. Your equestrial flourish does not appear in Spenser; your trussed-up gelding does not merit mention even by that master of fantastic allegory. Even Sir Newton, sir, would despise it: he would not permit your mule to poke its bedizened brow through a second story window, sir, as it does in the little sketch you sent. Sir Newton’s Theory of Gravitation would not allow it. I do not stand upon good taste, sir, nor decency, nor mere elementary good breeding; the very Laws of Physics reject your proposal.

‘Wuthering Heights’ is not a beautiful story. It is cruel and coarse; it can be crude. My hope for it is that it might teach us a lesson about remaining true our inward spirit. In successive generations, we might learn that the oppressive force of history, of society, of the world—which would have us sell our souls to become crooked, monstrous creatures— must be, can only be, conquered by remaining true to ourselves, rather than the dictates of our forefathers and society.

Sir, to do so, we must preserve our dignity. We must create stories and objects with meaning and with integrity. We must not seek to please masses, and our own base natures. We must be original, hard-working, honest, and true.

All this we must do—without the aid of a unicorn.

Sincerely,

Ellis Bell

Thomas Newby, publisher, to Emily as ‘Ellis Bell’; London, 7 December 1847

Most Wonderful Sir,

If C is to remain obstinate, we shall have to content ourselves with the subtitle. It is a shame, though.

On the subject of the ‘equestrial flourish’—I love it! This is exactly what I mean: its bedizened brow, its noble prong, &ct.: “Truth is Beauty”! Exactly as you say—remain true to your inward spirit, conquer the oppressors! &ct. &ct. I love it—it shall be done, and with a unicorn. Excellent—bedizened brow—your turn of phrase—defies the Laws of Gravity, Theories of Physics—tramples down Sir Isaac Newton with pearly hooves of glory—excellent. It is going to go over perfectly; you will see. 42/6d—‘Jane Eyre’ only went for 31/6d.

It is off to Press now; we shall soon see the result. This idea of the equestrial flourish—you are right, Boz gratifies us with a hopeful ending—the equine augmentation: hardly necessary. I will put the suggestion instead to H.B. Ogden’s Publisher—‘The Wire’ might have use of elves, serpents, the undead, &ct. &ct.

I remain, hopeful for the success of your work,

Yrs most truly,

T C Newby