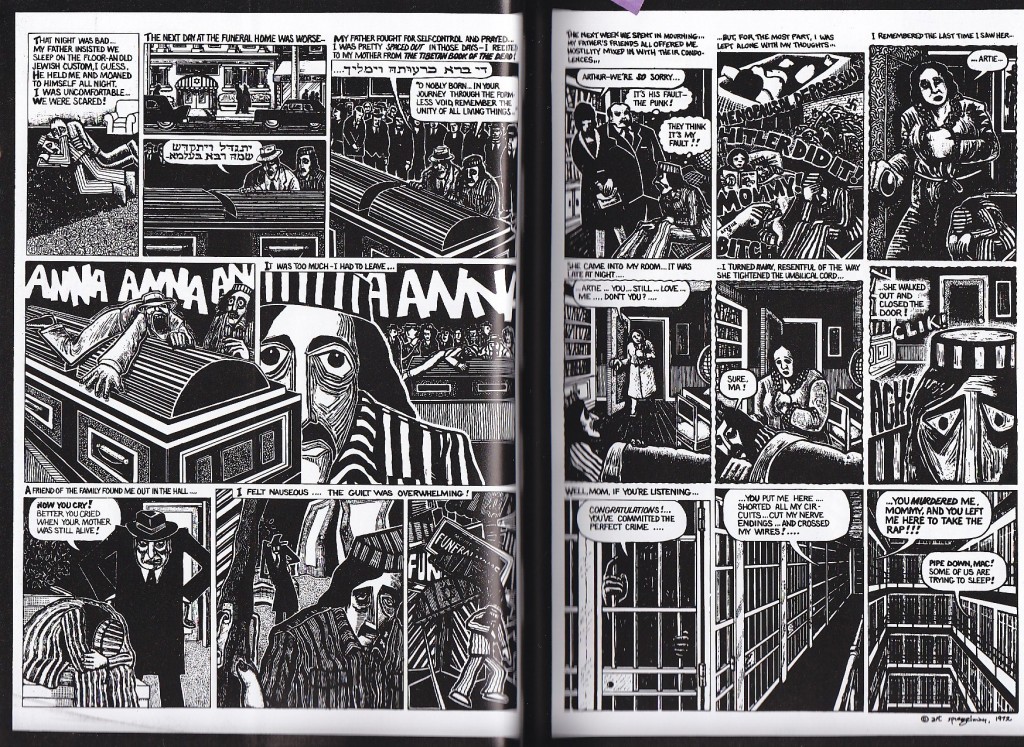

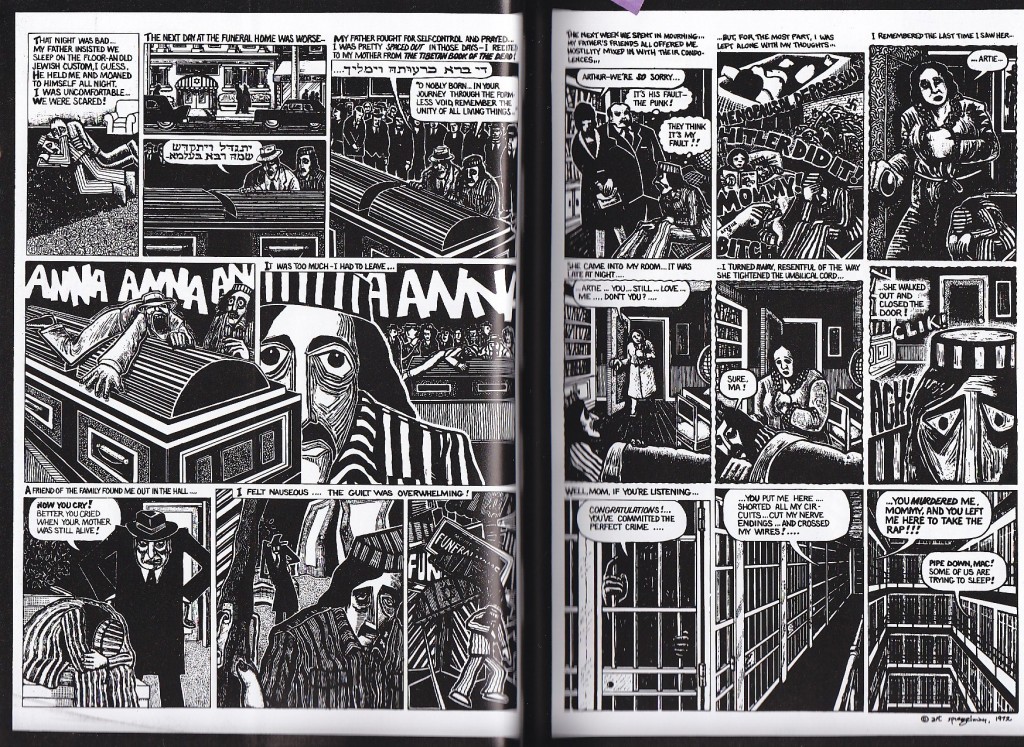

I hate Maus. Let me count the reasons why. I’m not allowed to hate it, for one thing; I always find that annoying. I’m not crazy about portraying Jews as mice and Poles as pigs and so on (I won’t go into why – better critics than I have already beaten that horse). (OK, I can’t help it – Nazis were humans who killed Jews, who were also human – people killing other people, not one species killing another species, not cats hunting mice, for heaven’s sake.) (Also, pigs? It doesn’t really matter to me whether he meant that insult or not; that’s the kind of thing that happens when you start getting cute about genocide.) I’m full on offended by “Prisoner on the Hell Planet” and Spiegelman’s tossing the word “murder” around. (That story is about his mother committing suicide, and he says, “You murdered me, Mommy, and left me here to take the rap!” He also calls his father a murderer for burning his mother’s journals without letting Art see them.) I could write essays about each of these topics, but I’m going to stay focused (well, focused for me) on my main problem with Maus, which is that I believe it’s morally wrong to batten on the pain of your people.

Yeah, yeah, yeah. I know. Postmodernism. I’m aware of it. And narratives help us understand atrocities like the Holocaust. And the children of Holocaust survivors experienced their parents’ memories in a unique way. And how is it wrong for a writer to work out his demons by telling a story? Plus, mice are cute! Everyone loves mice. I don’t actually disagree with any of that, except maybe postmodernism, but there isn’t much I can do about postmodernism.

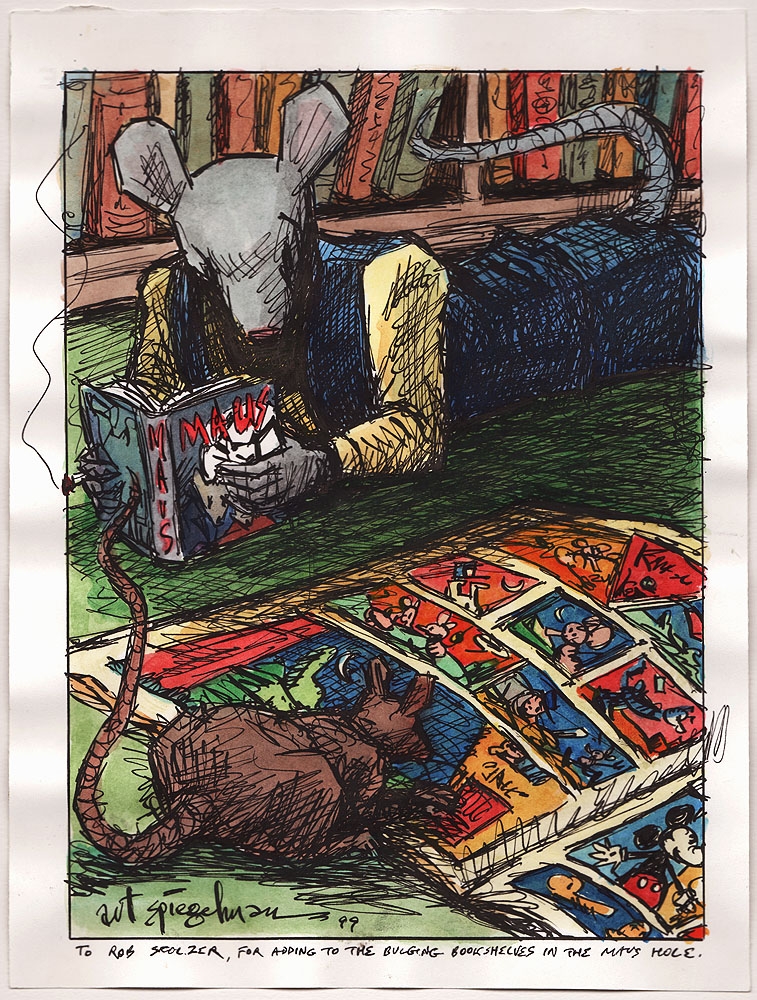

My objection is to Spiegelman grabbing his parents’ painful past and carrying it in a fireman’s hold through an obstacle course of writerly tropes to emerge, triumphant, a Pulitzer prize clutched in one hand and an Eisner award in the other, proud and satisfied about making the graphic novel serious and literary and worthy of a couple million graduate theses. He is excessively eager to define himself by his relationship to his parents – that is, my fucked up parents fucked me up, damn it. And who can argue? It’s the Holocaust! You can’t argue with the Holocaust. Of all the writers who have ever written about how their lives are ruined by their damned crazy parents, anyone laying claim to the Holocaust hits the mother lode. It renders anyone’s personal trauma unassailable and worthy of interest.

I am going to assume Spiegelman undertook this project as a way to come to terms with his own pain – an understandable motive, although the subsequent publication of more Maus and the egregious In the Shadow of No Towers might make one wonder, if one were mean and lacking in tact, about the relationship between Spiegelman’s career and his willingness to schmaltz up whatever major tragedy lands at his doorstep. Maybe it’s a chicken and the egg thing – he could be attracted to these themes because of the way his psyche was constructed (by his damned crazy parents). Either way, he thought it was OK to publish this story about mice Jews and cat Nazis, but he almost certainly didn’t expect everyone in the world to decide it was a brilliant masterpiece.

That probably means I shouldn’t hold it against him, but… But. (“Everyone I know has a big but,” sayeth the sage Pee Wee Herman; “What’s yours?”) This sort of thing reminds me of people who write true crime books. Beyond the “Look at me! Look at me! Be impressed by my pain!” thing (and isn’t that why God invented psychiatrists?), I can’t help thinking that putting murder out there for profit and some measure of fame (because we don’t publish things unless we hope people will read them) is wrong. Is it more or less wrong to exploit your own tragedy than someone else’s? On the one hand, you have more of a motive than simply latching onto a story that might sell (although that is part of your motive; otherwise, you’d keep a diary or something). You’re working through something that is, in some sense, yours. On the other hand, your own family becomes grist for the mill, and even if they acquiesce, you’re still using them.

I already hear the collective grumble of irritation saying it isn’t exploitation if it’s art. Art transmutes exploitation into something else, something with a higher purpose. And I believe that, too – to a point. What rises to the level of art? This isn’t the time or place to throw down on what art is or isn’t, thank god, but I don’t subscribe to the “50 Million Elvis Fans Can’t Be Wrong” theory. You know, “everyone else thinks it’s the best comic ever, so if you don’t think so, you can’t call yourself a sentient being and you also suck donkey balls.” Well, you say “sweeping metaphor,” I say “somebody get me some damned insurance so I can see a psychiatrist and tell them how my parents fucked up my life.”

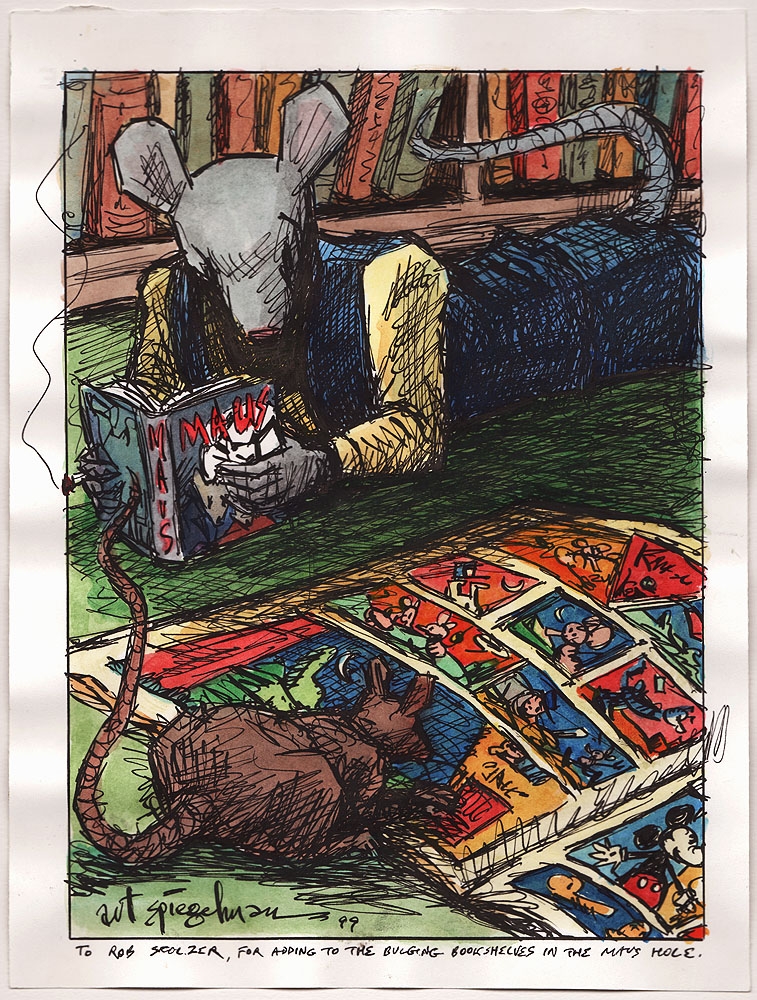

Not that I’ve actually read the thing, mind you. I don’t want to, I don’t need to, and you can’t make me. Does this mean I’m not allowed to have an opinion? It does not. I have picked Maus up countless times, willing the book to do anything but annoy me. If you are an educated and intelligent reader and accidentally let it out that you sometimes read comics, everyone assumes you love Maus. They start talking about it as if it had performed three perfect miracles. And because: 1) I hate to disappoint (oh, please – Kinukitty is the most gracious of creatures); and 2) I hate to miss out on things, I pick it up, I read a few pages, I put it back. (I actually have a similar relationship with Gravity’s Rainbow, which I used to keep with my horror books – except I think Gravity’s Rainbow really is art.) I have done this countless times and have probably read about half of the book, over the last 20 years. I have also read a certain number of essays and blog posts, and listened to a certain number of conversations, and rolled my eyes at a certain number of over-carbonated bookstore recommendations.

The brilliance of Maus would not coalesce for me if I could but force myself to read those missing pages. The Poles would still be characterized as pigs, the Holocaust would still be ugly, and the book would still stink of entitled self-pity.

__________

Click here for the Anniversary Index of Hate.