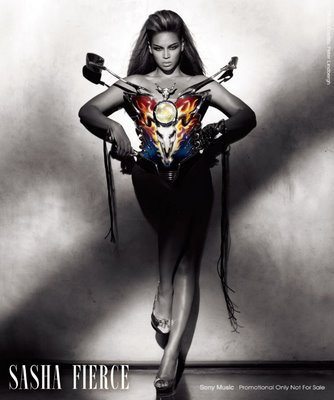

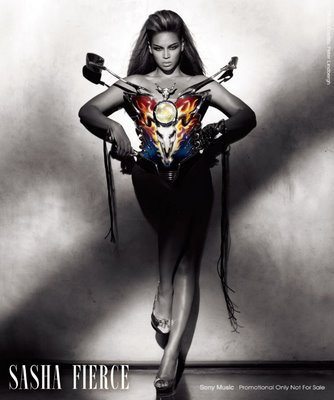

Sex and violence go together. Working fist in caress, they can help boost a film from PG to PG-13 and on up into R. They’re both adult, both corrupting, both potentially dangerous. That’s why it made sense when bell hooks looked at a Time cover with Beyoncé in her underwear and declared, “I see a part of Beyoncé that is, in fact, anti-feminist—that is, a terrorist—especially in terms of the impact on young girls.” Beyoncé’s sexuality is violent and damaging; it hurts people, especially young people. Sex is a weapon.

So sex and violence, in media, are commonly seen as continuous. But should they be? A little bit back I was talking with a class at Lakeland College about superheroes and violence. The teacher (and sometime HU writer) Peter Sattler, showed some clips from The Man of Steel, and asked the students to talk about the treatment of violence in the film. But the first reaction when the lights came up had a different focus. Taylor Levitt, one of the women in the class, pointed out that Henry Cavill was something special. “Wow,” Julie Bender, agreed, “I didn’t know Superman was so fine!”

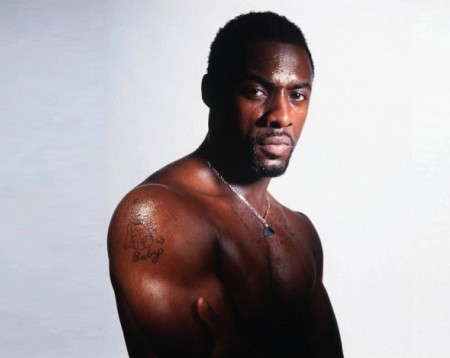

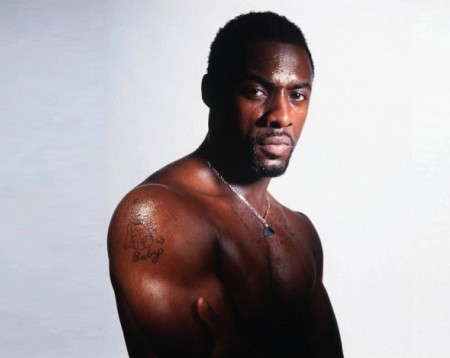

Henry Cavill’s fineness is widely agreed on (students weren’t even shown jaw-dropping image of him wandering about with his shirt off.) But what’s interesting in this context is the extent to which that hotness is superfluous to, or off to one side of, the film’s violence.

The genre pleasures of Man of Steel largely involve the usual action film devastation — things blowing up, cities being leveled, good guys hitting bad guys and vice versa. There is also, though, a line through the film about Superman restraining himself; gallantly refusing to use his powers, or refusing to fight back. And a lot of the energy, or investment in those scenes seems to come from Henry Cavill’s hotness; the pleasure of watching this perfect physique in spandex rendered all restrained and submissive. Superman even allows the authorities to put handcuffs on him, supposedly to reassure them, but perhaps actually for the pleasure of a clearly enjoyably flustered Lois Lane, acting as audience surrogate. You may go to the movie to see Superman commit hyperbolic acts of violence in the name of good. But you can also go, it seems like, to see Henry Cavill be sexily passive — to witness an erotic spectacle that is about seductive vulnerability, rather than destructive terror.

William Marston, the psychologist and feminist who created Wonder Woman, deliberately tried to exploit (in various senses) this tension between sex and violence. The original Wonder Woman comics are filled with images of Wonder Woman tied up elaborately with magic lassoes, gimp mask, and sometimes pink ectoplasmic goo. The point of all this, as Marston explained in a letter to his publisher, was to teach violent people the erotic benefits of submission

“This, my dear friend, is the one truly great contribution of my Wonder Woman strip to moral education of the young. The only hope for peace is to teach people who are full of pep and unbound force to enjoy being bound … Only when the control of self by others is more pleasant than the unbound assertion of self in human relationships can we hope for a stable, peaceful human society … Giving to others, being controlled by them, submitting to other people cannot possibly be enjoyable without a strong erotic element.”

Marston believed women were better at erotic submission than men, and that therefore women needed to rule so that men could learn from them how to submit. In his psychological writings, Marston referred to the women who would erotically lead the world as “love leaders.” Love leaders would use their sexuality to seduce the world to goodness and peace — just as the soulful-eyed, bound Henry Cavill guides viewer’s thoughts away from the super-battle plot and towards gentler pastimes.

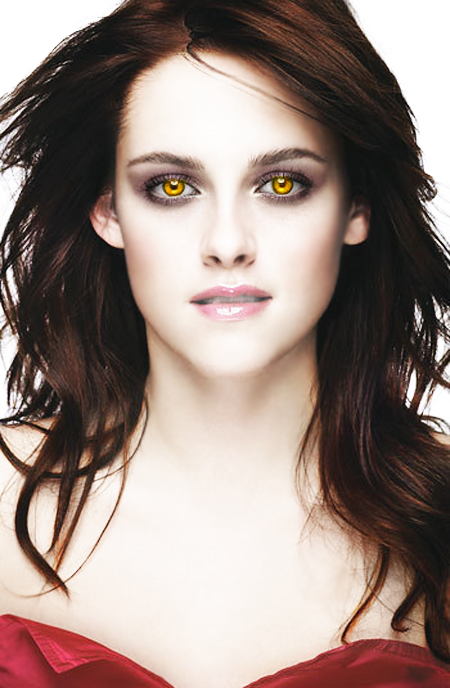

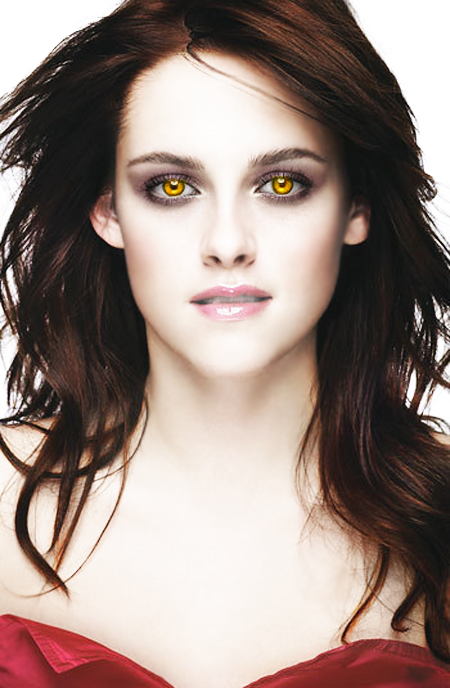

Of course, Marston was kind of a crank, and, in any event, it’s quite clear from Man of Steel that you can have eroticized submission and uber-violence both; you don’t have to choose one or the other. Still, you can choose one over the other if you want; it is possible, to use the erotic to undermine a narrative of violence. This is what happens in Twilight, for example — and it’s part of the reason that many people find the series’ ending so frustrating.

Stephenie Meyer wrote about super-powered vampires, and builds her series towards a climactic, brutal, all out battle. But the focus of Twilight is on the romantic relationship between Bella and Edward; on love, passion, and sex. As a result, Meyer doesn’t feel she needs to follow through on the genre promise of violence — the big all out battle never happens. The series has other interests, which makes a non-violent outcome possible. It’s not a coincident that Bella’s vampire power is literally to neutralize other violent powers, just as Marston hoped erotics could neutralize force. In Twilight, romance and conflict are set against each other, and romance wins. Sex trumps violence.

It’s tempting to conclude hyperbolically by calling Beyoncé a love leader whose command of the erotic will bring about world peace. But that’s no more convincing than calling her a terrorist. Sex isn’t going to save us anymore than it’s likely to doom us. Still, eroticism remains a powerful thing. It seems worth thinking about it not just as a danger, but as a resource — a way, at least, to imagine a world in which heroes don’t always end up hitting each other.

You can keep your hammer, Thor.