I was quizzing a friend of mine at a recent dinner party about her living in England as a kid. Ellen and her older brother attended Bishop Kirk Middle School in Oxford, where she had Philip Pullman for a homeroom teacher. He also gave her private guitar lessons while not busy teaching English and Maths (the course is inexplicably plural in England). This was the late 70s, a couple of decades before His Dark Materials made Pullman an internationally celebrated fantasy author. School plays were still his main creative outlet. He wrote one a year and staged it in the lunchroom with a curtain draped in front of the counter. Mrs. Dixon, the music teacher, composed the songs and thumped them out on piano.

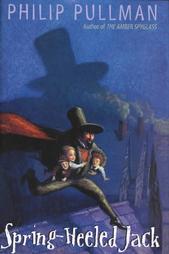

Ellen remembers virtually nothing else about the 1978 Spring-Heeled Jack, just that her brother played a sea captain and got to kiss the prettiest girl in school (who became a supermodel and married Simon Le Bon of Duran Duran). Pullman later adapted the play into a children’s book—which I’m holding in my hands right now. It’s part comic book, which is appropriate, since Spring-Heeled Jack is also England’s first superhero. “In Victorian times,” writes Pullman, “before Superman and Batman had been heard of, there was another hero who used to go around rescuing people and catching criminals.”

Pullman’s illustrator, David Mostyn, draws Spring-Heeled in a cape and top hat—which is disappointing if you’ve seen any of the Victorian illustrations. I don’t know how Pullman dressed his middle school actor (“the costuming was all very much pulled-together,” Ellen says), but Alfred Burrage’s 1886 penny dreadful describes “the tight-fitting garb of the theatrical Mephistopheles” which “covered him from his neck to his feet” and “made him look like a huge bat, with a body of brilliant scarlet.” This “most hideous and frightful appearance” also included a “black domino” mask, claws “of some metallic substance” (adamantium perhaps?), a “small black cap” with a “bright crimson feather” (though he sometimes substituted a “large helmet” or “the head of an animal, constructed out of paper and paste”), a “high-heeled, pointed shoe” and “something like a cow’s hoof, in imitation, no doubt, of the ‘cloven hoof’ of Satan” (“It was generally supposed that the “springing” mechanism was contained in that hoof”), and a “capacious cloak,” the flaps of which distended in flight “until they resembled a pair of wings.”

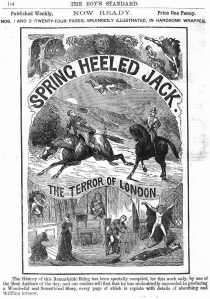

When Burrage rebooted in 1904, he added a batcave and then stole an escaped-fugitive-framed-for-treason revenge plot from The Count of Monte Cristo. Burrage wasn’t Jack’s first chronicler though. An anonymous serial sprung up in 1867, with a title lifted from John Thomas Haines’ 1840 play, Spring-Heeled Jack, The Terror of London. If that subtitle doesn’t sound very superheroic, it’s not. The play was inspired by the possibly hysterical reports of a real-life assailant who terrorized the suburbs of London in 1838. According to The Times, a “young man in a large cloak” tore at one victim’s “neck and arms with his claws” and “vomited forth a quantity of blue and white flames from his mouth.” Police suspected a carpenter too drunk to recall anything of the night, but spreading rumors named the devil and/or Henry de la Poer Beresford, the Marquis of Waterford. The mayor of London received an anonymous letter accusing an individual from “the higher ranks of life” of accepting a wager to garb himself “in three disguises—a ghost, a bear and a devil” and accost and so deprive “ladies of their senses.”

True or not, the tally of senseless ladies soon climbed to thirty with the Morning Post reporting how “females” were “afraid to move a yard from their dwellings.” If Jack was the devil, then Old Nick must have just flapped in from the Kentucky frontier where he was routinely sighted as the animal-headed, demon-avenger Jibbenainosay in Robert Birds’ 1837 Nick of the Woods. The devilish Marquis was never arrested, but two of his imitators were. Spring-Heeled Jack, however, had already bound into legend. The name—originally just a reference to the culprit’s elusiveness—reverse engineered itself the superpowered ability to leap over coaches and houses by supernatural and/or mechanical means. “Spring-Heeled Jack” also became a standard term for unsolved assaults and ghostly sightings, culminating with that 1888 Whitechappel serial killer dubbed “Jack the Ripper.”

I’d say Spring-Heel traffics a lot with the Faust legend too. Mephistopheles migrated from German to England in 1592 via Christopher Marlowe’s The Tragical History of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus. The alchemist wagers his soul to employ the devil as his personal servant. The Marquis’ wager does Faust one better—he becomes the devil himself. Burrage trades in the Marquis for a dashing young baronet, further ennobling the nobleman in the process, but the plot is the same. An aristocrat transforms himself into a man-bat to play “the part of the Good Samaritan,” a Victorian Batman protecting distressed damsels from burglars, rapists, and swindling relatives cheating them of their inheritances.

Mephisto (the truncation popular with Marvel) continues to terrorize the multiverse. He started tempting the Silver Surfer back in 1968, before contracting the Ghost Rider for his soul, duping the Scarlet Witch and Vision out of parenthood, and, in a recently flamboyant retcon, swapping Spider-Man his aunt’s life for his marriage. Mephisto also may or may not be responsible for the damnation-threatening hate mail Phillip Pullman received after his last identity-splitting novel, The Good Man Jesus and the Scoundrel Christ. “The letter writers essentially say that I am a wicked man, who deserves to be punished in hell,” said Pullman. “Luckily it’s not in their power to do anything like sending me there.”

If Pullman did sell his soul for literary success, it was in the 1980s when sales for his children’s novels allowed him to quit his day job at Bishop Kirk Middle School. Ellen remembers the first, Count Karlstein, as another of her teacher’s beloved school plays: “Those plays were just so fun, so fantastic—he really was the best teacher. A born storyteller.” Spring-Heeled Jack ends with a mad dash to a disembarking ship where the tale’s Middle School-aged children are reunited with their father, and then the “strange, devilish figure” vanishes without a parting word.

“I wonder,” says Rose, “what Spring-Heeled Jack will do tomorrow night?”