I first encountered Zbigniew Libera’s LEGO concentration camp kits (1996) when I was writing on Art Spiegelman’s Maus. Both Libera and Spiegelman, famously, used a medium typically associated with children in a self-effacing attempt to depict the Holocaust. Libera’s work offered an interesting counterpoint to Maus because, despite the apparent conceptual similarities, while Spiegelman’s masterpiece has been almost universally celebrated, Libera has been called an anti-Semite, has been asked to withdraw his work from exhibitions, and has been accused (perhaps correctly) of offering a glib pop-culture commentary on the largest and genocide – the most terrible event – in human history. I wanted to examine the two texts beside one another in order to work out what made them different and how each reflected the politics of Holocaust representation. Ultimately, as inevitably happens, the work took a different shape and when the time came to submit the final draft of my manuscript I had said everything I wanted to say about Maus but Libera had been reduced to a footnote and, finally, removed entirely. The Lego System kits still bother me, though, and I would like to explore why they bother me here.

Libera worked with the LEGO Corporation of Denmark to produce three kits, each made up of seven boxes of Lego. Each box contains all of the materials needed to construct a Lego simulacra of some aspect of a Nazi death camp. Boxes include buildings, a gallows, inmates, guards, and barbed wire. The scenes depicted include a lynching, the beating of an inmate, medical experiments, and corpses being carried from the gas chambers.

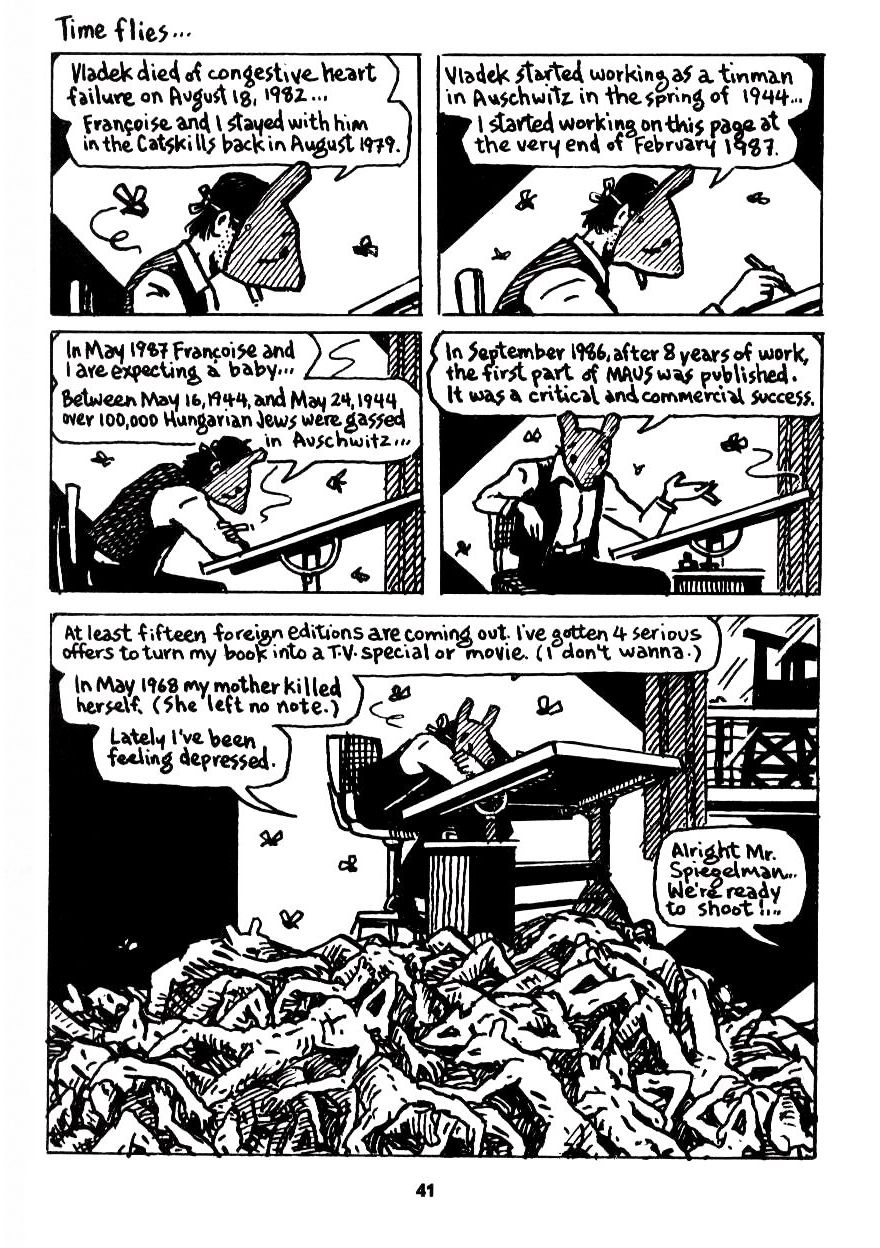

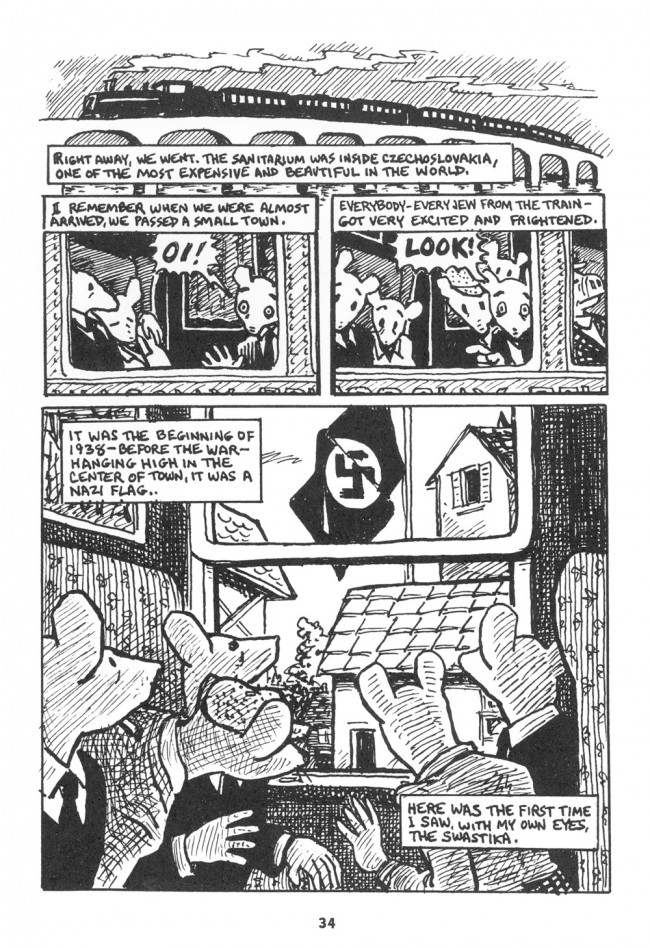

One way we might read Libera’s work is as a hyperbolic form of historiographical metafiction, a term coined by Linda Hutcheon in A Poetics of Postmodernism to describe works which show ‘fiction to be historically conditioned and history to be discursively structured.’ By adopting an abstract form and a demonstrably impossible alternative history, certain texts, Hutcheon argues, point implicitly to the failure of any representation to capture the ineffable reality of historical events. The impossibility of articulation is doubly true of the Holocaust which, as many, many critics and writers have argued, defies our capacity for either imagination or expression. If we were to read Libera’s Lego System in such a vein then we would understand his use of a toy to depict the Holocaust as (like Spiegelman’s Maus) demonstrative of the failure of any means of articulation to approximate to the torture, humiliation, and murder of millions.

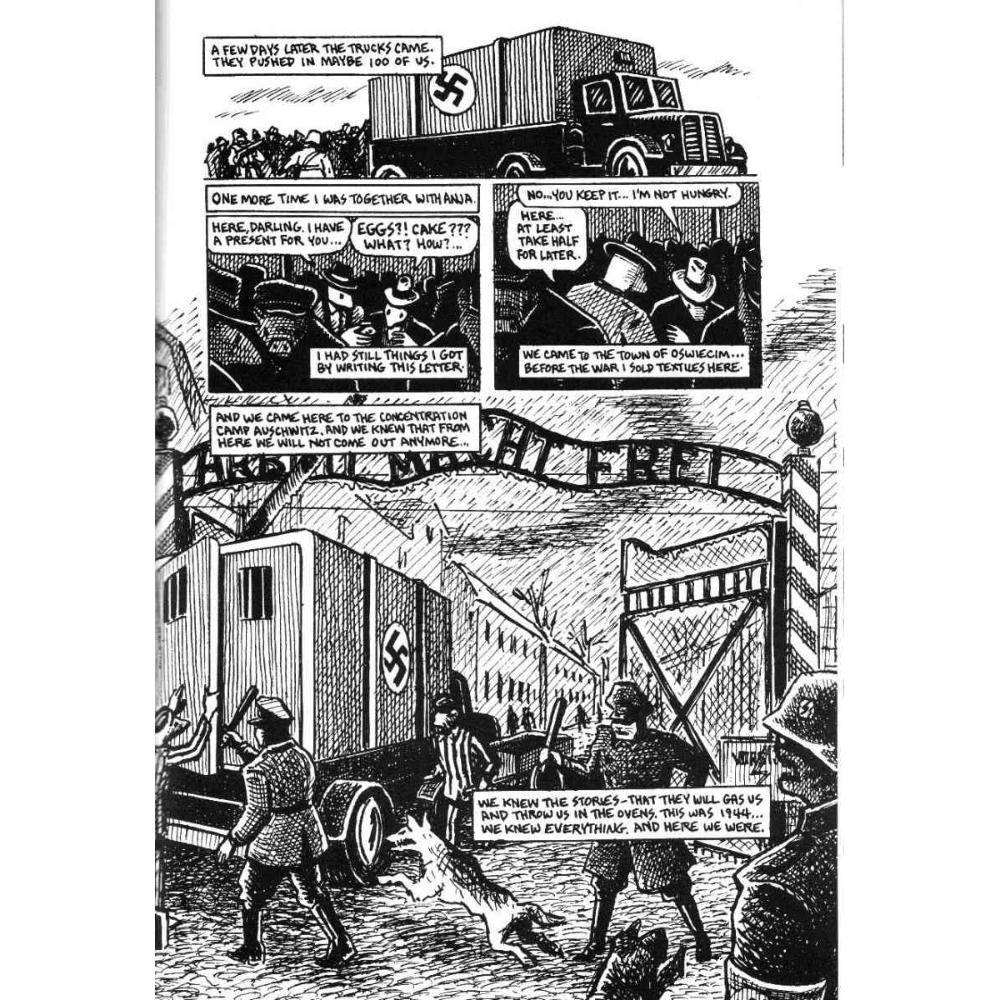

I understand this line of argument but I can not subscribe to it as a blanket excuse for every ironic or self-consciously inaccurate attempt to depict the Holocaust. Concessions made to the concept of historical accuracy with regards to the Nazi killing project are in danger of offering a degree of legitimacy to more extreme revisionist perspectives. Under the umbrella of representational impossibility Libera’s work unnecessarily distorts what occurred; his commandant, as Stephen C. Feinstein argues, bears more similarity to the Soviet gulag than the Nazi death camp and the entry gate lacks the well-known inscription. He appears to see the historiographical metafiction argument as license to abandon any form of historical accuracy.

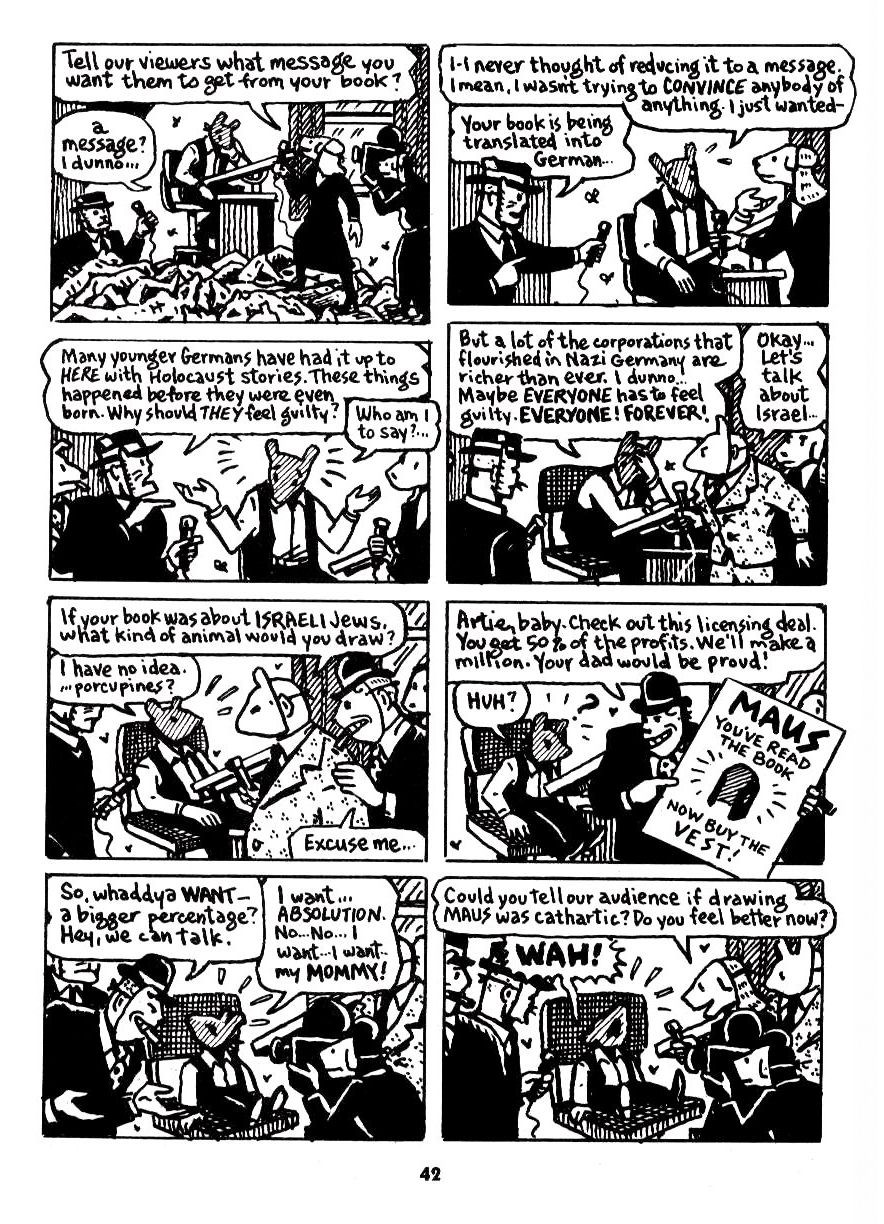

Even if full representation is impossible, I can not help but feel that where we can offer accuracy we have a moral obligation to do so. The ‘how’ of the Holocaust, Robert Eaglestone argues, should never be neglected in favour of artistic license. Inaccuracies (of which there is a wide spectrum from allegory to outright lies and denial) are dangerous to understanding. To foreground a fundamental responsibility to historical truth in Shoah art and literature is to echo the final line of Levi’s introduction to If This Is A Man: ‘[i]t seems to me unnecessary to add that none of these facts are invented’. After the terror inflicted during the Holocaust, the Nazi’s attempts to destroy the camps and remove evidence of what had gone on, and subsequent attempts in some quarters at revisionism and denial, an earnest attempt at fidelity, even if true representation is impossible, is, I can not help but feel, imperative. It is here, incidentally, where Libera and Spiegelman part ways – while Maus articulates a failure to represent the Holocaust, Spiegelman went to great pains to research and, where possible, accurately depict his subject.

It would be easy, then, to simply dismiss Lebera’s Lego System as an ironic, transparently provocative, and deeply offensive play on, what is for others, an earnest and hard-fought attempt to bring some understanding to the worst event in human history. While I stand by my earlier assertions, I find it hard to dismiss the Lego kits as entirely vapid. I find the fact that the kits were built using existing Lego parts (modified slightly using paint in some cases) as an unsettling assertion of Horkheimer and Adorno’s argument that rather than being an aberration in an otherwise rational society, the anti-Semitism which informed the Shoah had roots in the pervading logic of pre-World War II European cultures. The component parts of genocide, the Lego kits could be read to assert, not only pre-date the Holocaust, but continue into modern society. The Holocaust did not occur in spite of, but relied upon the industrial model which built, and continues to build modern civilisation (the factory, trains, timekeeping, coordination, a drive toward efficiency). The reproducibility of the Lego medium (Libera made three sets but some people asked if they would become commercially available) suggests, terrifyingly, that the events (loosely) depicted can not be safely confined to history, but can easily be reconstructed from those apparently innocuous elements upon which modern society has been built. As Spiegelman asserts ‘Western Civilization ended at Auschwitz. And we still haven’t noticed.’

I am, of course, not the first writer to find myself grappling with these questions when it comes to Holocaust representation, and in many ways I find myself treading already well-worn pathways. I find myself simultaneously recoiling from the apparently glib treatment of the Holocaust in Libera’s Lego System, while simultaneously wondering if the confinement of the Nazi killing project to history (of which the argument for Holocaust exceptionalism is a component) is a way for us to avoid confronting the possibility of its reproducibility.