There’s a style of talking about the Christian God that you find in rural corners of the American South where there are Free Will Baptists and Pentecostal Holiness churches. Imbued with images and rich with metaphor, it’s also thickly oral, repetitious and rhythmic – reading transcripts of sermons aloud is like holding pebbles of words in your mouth:

I was voted in to pastor a church away down in southeast Alabama. I felt like I was drifting into a paradise opportunity to work for God, but really I was headed for the jaws of a vice on the Devil’s workbench. What I didn’t know what that the young people outvoted some of the old-time goatheads which was trying to bring in an older minister. They had future trouble up their sleeves…[they said] we are going to bring our minister to church and he is going to take the pulpit.

“When the other people at the church heard this, they were ready for a fight. One rough sinner-man came to me and said “I have a real sharp knife and I ate peas and cornbread in prison before and I can do it again. Don’t worry, no one is going to take your pulpit. My knife is sharp and I’ve been in trouble before.” So I woke up in a vice between a prospering church and a blood-shedding fight. I wanted to preserve peace, but that ain’t easy, because the Devil has got me in that vice time after time…Preachers think they got power just by preaching and that sinners will get saved. You can’t run sinners out of church. You have to run them into church and make it a soul-saving station for God.”

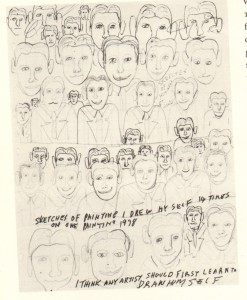

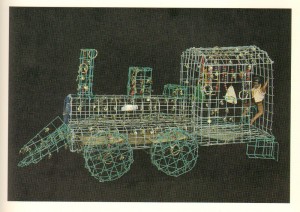

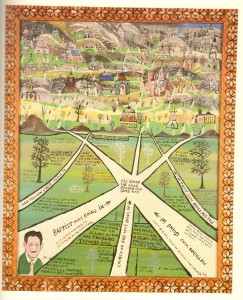

Howard Finster (who wrote and drew the above) was a particularly strong example of this way of talking about God. It was common, among people of his generation, in the Pentecostal sects of his part of the south, where the Holy Spirit gets a seat at the table and the church elders speak in tongues, but even there his imagination was more vivid than most.

His paintings, which I linked to briefly a few days ago, share the same sensibility as his sermons – a mixing up of images and metaphors from sacred and secular life, mixing that he thought was essential to his evangelical purpose.

In these places, deep in the rural South, where the nearest town of any size is hours away and the churches have had the same families in the same pews for 100 years, religion stops feeling like a choice, because culture is so saturated with faith it’s not something you believe, it’s just the way things are. “Ashes to ashes, dust to dust” isn’t just a phrase in a funeral: it describes that sense that everything in the world is made of the same stuff and that stuff is God: the trees and the fish and the people and the boards of your porch and the bricks of your church.

Howard Finster draws the psyche of that place.

It’s come up several times that asking R.Crumb to “have some imagination, damn it,” (in Genesis, at least) is somehow tied up with asking him to be more religious, or that seeing his imagination as falling short is somehow due to mistakenly looking for signs of belief. I think, though, that it does Howard Finster’s imagination a great disservice to attribute it to his faith. There are too many faithful people who don’t have it. I wish faith did automatically produce it: then we’d have more art like his.

============

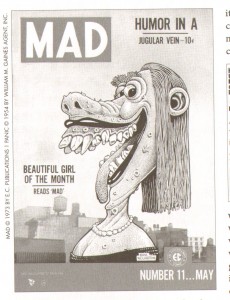

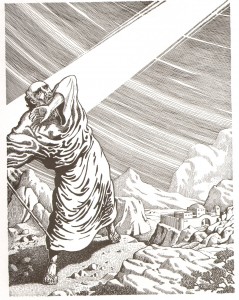

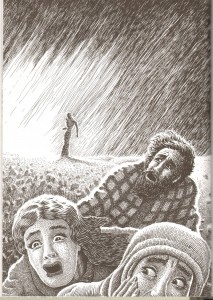

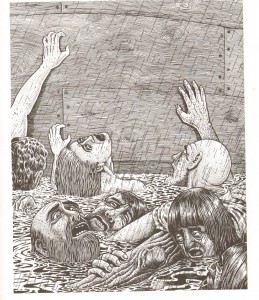

Cartoonist Basil Wolverton was also a believer when he began illustrating Bible stories and verses for evangelist Herbert Armstrong in the early 1950s. Wolverton had been drawing comics since 1925 and was drawing for Mad at the time he started illustrating the Bible. His cartoons influenced Crumb and other underground cartoonists – he drew grotesque, weird, exaggeratedly humourous characters that, despite his protestations about intent, were viewed as highly sexually suggestive.

His Biblical illustrations, unsurprisingly, are more straightforward and serious, although the exaggerated sensibility sneaks through. In the introduction to “The Wolverton Bible,” his son Monte observes:

Wolverton’s challenge was to portray the Biblical accounts accurately without tramautizing children too much. Yet from his background in comics, he understood that children actually enjoy a certain amount of violence (how it effects them is another topic.) In this way he was a pioneer for later comic artists, beginning in the 1970s, who would bring a more realistic interpretation to graphic depictions of the Bible…he never backed down from his position that the Old Testament needed to be depicted for what it was.

(Sound familiar?) Like Finster’s, Wolverton’s approach is consistent with the declamation style practiced in his church, but Wolverton’s church was very different. Monte Wolverton describes Herbert Armstrong’s preaching style as “newscaster-like” and “devoid of churchy language.” Although essentially a one-man-show when Wolverton first became involved, Armstrong’s church, called the Worldwide Church of God, had become extremely rule-bound and institutionalized by the end of the 1960s – members who disagreed with church teaching were “disfellowshipped.” (It was not a typical fundamentalist church, however, as it did not prevent drinking, dancing or other social activities.) Wolverton himself was a jovial, congenial and funny man who loved to entertain. His drawings reflect this mixed vantage point: the serious, “newscaster-like” declamation with a great appreciation for humanity and personality.

It seems obvious that Wolverton’s treatment of the Bible was more influential on Crumb than Finster’s, although I have no evidence that Crumb saw these Biblical drawings before beginning his work. Crumb’s Bible strikes me as very much the literal Evangelical Bible, though, so it wouldn’t surprise me if there was genealogy through this path.

What’s more difficult to account for, for me personally, is the greater aesthetic impact I feel from the Wolverton drawings, since they are in many respects so very similar to Crumb’s. In comparison, I think much of my dissatisfaction with Genesis does in fact come from two formal elements of the comic idiom: the grid, which provides a repetitive overarching composition even when the in-panel composition is varied, and the transformation of the prose text from its familiar, “native” graphic presentation in the columnar numbered pages of the Bible, into the comics idiom of captions and balloons. Text is, for all its abstraction, also a visual medium, and the flow and sound of the text in normal prose presentation is governed by different interactions than the ones in Crumb’s comics version.

My lack of appreciation for this – my sense that more is lost than is gained – is without doubt my limitation, not Crumb’s, and in this particular matter, an issue of personal aesthetic preference. But the comparison raises questions about the impact and effect of “sequential art”: I think because most people who read comics have an affinity for these elements of the idiom, they’re often accepted unquestioningly, without critical challenges or evaluation. A “nothing left out!” illustration job is a translation of sorts – normally the prose Bible is very aural; in Crumb’s book that aurality is replaced with the visual. The oft-described effect of “making the pictures narrate” is very palpable here – Crumb is without doubt successful at that effort – but to what end? Is it really just a “translation” into the comics “language”?

I think it may be — while Finster in particular can stand up against the more elite Biblical art that Suat drew on in his comparison and Wolverton’s approach is at least highly representative of his particular individual reading, Crumb’s is much less an individual reading than either. His very successful effort to humanize the Biblical characters resulted in a dehumanization of the experience overall. This perhaps shows us Alter’s error: it is not the concretization of images that marks the limit of the comics form at this moment in history, but instead the lack of imagination regarding the ways in which illustration can be fully literary without being tied relentlessly to sequence, grid, and narrative. Some experimental cartoonists are working to imagine new notions, but the far-more-common reliance on sequence to capture the spirit of literature – well, it only “captures” it, like a wild animal kept in a tiny cage.

Howard Finster described himself like this: “To do art like them fellas do in the books, it would take months. I’m a cartoonist. I don’t fool with details like that.” Without those details, an imagination like Finster’s makes all the difference.

============

Images and quotations in this post are taken from: “Howard Finster, Man of Visions: the Life and Work of a Self-Taught Artist” by J.F. Turner (Knopf, 1989) and “The Wolverton Bible: The Old Testament and Book of Revelation through the Pen of Basil Wolverton,” Monte Wolverton, compiler (Fantagraphics, 2009).