“Both the Joker and Hannibal Lecter were much more fascinating than the good guys,” says Talking Heads singer David Byrne. “Everybody sort of roots for the bad guys in movies.” Byrne was explaining why he wrote “Psycho Killer,” the opening song from their Jonathan Demme concert movie, Stop Making Sense. Demme also filmed The Silence of the Lambs, but that’s almost two decades after Byrne wrote his song, so the origin story doesn’t make much sense either.

Byrne is also a fan of Dadaism and adapted a Hugo Ball poem for the Talking Heads. “I Zimbra” is a string of nonsense syllables, reflecting Ball’s Dada Manifesto: “to dispense with conventional language” and “get rid of everything that smacks of journalism, worms, everything nice and right, blinkered, moralistic, europeanised, enervated.” Similar new wave beats were sweeping through Paris in the early teens where Ball’s avant-garde cousins were rooting for France’s pulp fiction psycho killer, Fantômas.

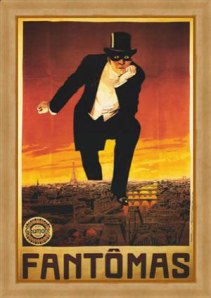

I’m no expert in French surrealism, but I’ve stood mesmerized in front of more than one Magritte painting. He, like Jean Cocteau and Guillaume Apollinaire and André Breton, were mesmerized by the figure of a “masked man in impeccable evening clothes, dagger in hand, looming over Paris like a somber Gulliver.” That’s John Ashbery’s description of the iconic cover art for Pierre Souvestre and Marcel Allain’s 1911 Fantômas, the first in a series of 38 novels featuring the empereur du crime.

The bigger mystery is how a Pulitzer-winning poet came to write the introduction to a reissued translation. Maybe it’s because Ashbery is, according to Ashbery, “sometimes considered a harebrained, homegrown surrealist whose poetry defies even the rules and logic of surrealism,” a description that could also suit Souvestre (a failed aristocrat-lawyer turned automotive journalist) and Allain (Souvestre’s secretary, ghostwriter, and later husband to Souvestre’s flu-widowed wife). Ashbery calls them both “hacks,” their prose “hackneyed,” and their narratives “crude.” Yet Ashbery’s harebrained forefathers declared Fantômas “extraordinary,” its lyricism “magnificent,” and the serial a “modern Aeneid.”

Apollinaire did throw in a “lamely written,” so the surrealists’ praise isn’t entirely surreal, but it doesn’t begin to explain the character’s Gulliver-sized impact on French culture. Ashbery adds to the mystery by listing Fantômas’s many and superior ancestors, including Manfred and Les Miserables. He also mentions the popularity of Nick Carter in France at the time, but he misses how much Souvestre and Allain pilfered from the American pulp. The authors allude to “Cartouche and Vidocq and Rocambole,” but their psycho killer’s most immediate predecessor is Nick Carter’s arch-nemesis, Dr. Quartz.

Carter’s “hack,” Frederic Van Rensselaer Day, introduced the psychopathic genius twenty years earlier. Quartz “wished to defy the police; to defy mankind, because he believed himself to be so much smarter than all other men combined.” He is Nietzsche’s superman, indifferent to “rightdoing and wrongdoing, as we define the two terms” and to “anything human, animal, moral, legal, save only his own inclination.” If you like the scene in Silence of the Lambs where Dr. Lecter displays his gutted guard like an abstract art installation, you’ll just love “Dr. Quartz II, at Bay” when the doctor embalms a railroad car of victims and arranges them like waxworks playing a game of cards. Or if you like Alan Moore’ Killing Joke when the Joker rigs a funhouse ride to project photos of Commissioner Gordon’s raped and crippled daughter, wait till you see how Fantômas can pose a corpse at the reins of a runaway coach or inside a clock bell so blood rains down with the clanging of the hour.

It would be easy to call them all “evil.” It’s the term we like to use for Adolf Hitler and Osama bin Laden. But the word is meaningless. It pretends to define what it merely describes. The real horror, the thing that should keep you awake at night, is the absolute absence of evil in the motives of those who commit it. Adolf and Osama were trying to make the world a better place. They thought they were the good guys. David Byrne finds the Joker and Hannibal Lechter fascinating because they’re make-believe. They don’t make sense because they can’t. There’s no root cause to their actions. There’s no mystery to solve, just endless installments.

Nick Carter, le roi des détectives arrived in Paris cinemas in 1908 to rain down multiple sequels and knock-offs, including Louis Feuillade’s Fantômas film adaptation. So Feuillade’s equally acclaimed follow-ups, Les Vampires and Judex, are knock-offs of a knock-off, with scripts improvised around the same actors, costumes, plots, and character types. Souvestre and Allain hand-cranked their prose just as sloppily. Though they exists solely in “conventional language,” their novels may somehow still answer Bell’s directive to “get rid of all the filth that clings to this accursed language . . . the word outside your domain, your stuffiness, this laughable impotence, your stupendous smugness, outside all the parrotry of your self-evident limitedness.” Replace “Dada” with “Fantômas” and Bell’s Manifesto reads:

“How does one achieve eternal bliss? By saying Fantômas. How does one become famous? By saying Fantômas. With a noble gesture and delicate propriety. Till one goes crazy. Till one loses consciousness. How can one get rid of everything that smacks of journalism, worms, everything nice and right, blinkered, moralistic, europeanised, enervated? By saying Fantômas. Fantômas is the world soul, Fantômas is the pawnshop. Fantômas is the world’s best lily-milk soap. Fantômas Johann Fuchsgang Goethe. Fantômas Stendhal. Fantômas Dalai Lama, Buddha, Bible, and Nietzsche. Fantômas m’Fantômas.”

Ultimately Ashbery declares Fantômas a Cubist charade (Picasso and Gris were fans too), and yet one whose “popularity cut across social and cultural strata.” Like a dagger’s blade, you could say. The best monsters are never slain, never contained, but are always plotting new and paradoxically comforting horrors between episodes. A story’s meaning only emerges when it’s over, and so Fantômas was meaningless to the generation who embraced him. He made everything stop making sense.

Ball calls for new words, for an invented language of nonsense—which is what I hear when David Byrne sings the chorus: “Psycho killer, kiss kiss say.” I obviously don’t know much French. But no one, not even the French, know Fantômas.