Having only just escaped my own teenage years, I have a lot of mixed feelings about adolescence. Listening to people older than me, I often hear that teenagers are mean, histrionic little know-it-alls with nothing but angst, self-absorption and empty-calorie cynicism flowing through their veins. And having only just been a teenager myself, I can’t also say there’s there is no truth to that; teenagers are insecure, they’re hormone-addled, and in the 21st century have access to an array of technologies that let them broadcast versions of themselves they might later wish to live down to the entire world. But even if contemporary wisdom dictates that adolescence has always been a time of angst and cynicism, there seems to me something far more cynical about the way that teenage suffering has been normalized, made into something that everyone between the ages of 13 and 19 should anticipate. Emotional suffering doesn’t simply arise in a vacuum; it is almost always created through external conditions, and even the most banal teenage whining should be assumed to be grounded in some outside social forces. But what is the cause? Is it all hormones? Is it insecurity? Is it just a natural part of “finding yourself,” as so many young adults narratives stress? These could all very well be central factors, but a recent strain of young adult narrative – the “kill your friends because you are forced to” kind – seems to suggest something more systemic at play.

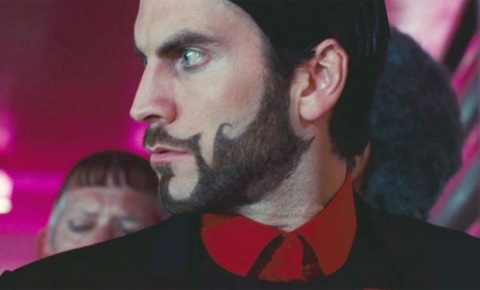

The general premise of Avengers Arena, an ongoing series written by Dennis Hopeless and illustrated by Kev Walker, is one that’s become strangely familiar in the past 5 or so years; a group of teenagers, isolated and rendered helpless by some outside force or organization, are forced to run around killing one another until only a single person, the Übermensch among them, still stands. Some of them will refuse to fight (and they die quickly), some of them will try to run (and they die just as quickly) and some will take to the game immediately, thrilled to finally have the chance to release their inner demons and kill everyone who’s ever said something rude to them. But mostly, it’s a brutal game of survival, a literal dog eat dog nightmare designed to breed the most ruthless, brutal and efficient members of society. Sounds like High School, right?

We all probably know where this train starts; when Koushon Takami’s novel was released in 1999, and adapted into a film in 2000, Battle Royale created an enormous stir in Japan and a significant one abroad. Coming out at a time when Japan was just getting out of its Lost Decade (only to fall headfirst into another one, as fate would have it), Battle Royale combined the titillation of a slasher film with the concrete issues facing Japan’s youth at the time, namely the plight of the precariat (precarious proletariat, those unable to find work beyond temporary, part-time positions) and the consequences of a prolonged recession that forced young people to go at each other’s’ throats constantly in their attempts to secure stable employment, which was thought of as a birthright just a generation before. It takes place in an alternate-world 1997 Japan, where the country’s economy has collapsed and unemployment has become so rampant most students have stopped attending school, seeing it as a waste of time. Seeing the very foundations of their society crumble, Japanese authorities pass the Battle Royale Act, stipulating that once a year a randomly chosen 8th grade class must fight to the death until only one student remains standing.

While the Battle Royale bills itself as a celebration of the idea of survival of the fittest, it is clearly a battle of the most aggressive; any alternative means of survival, such as hiding, escaping or simply choosing not to fight are cancelled out with the inclusion of an island location, detonating collars and mines that force students to continuously come closer to one another until all are dead. Class 3-B, the class chosen for the Battle Royale, initially has no idea what is going on when they’re kidnapped and spirited away, but soon after the game starts, several students take to it quickly, especially Kazuo Kiriyama, a mute, psychopathic character who willing signed up for the Battle Royale because he thought it might be fun. The movie is in turn a character study and a bloodbath, intimately concerned with the psychologies and motivations of these young people forced to kill one another. We have Mitsuko Souma, a child sexual abuse victim who ultimately killed her abuser and learned to never trust anyone, Hiroki Sugimura, a boy whose tracking device would let him easily win the game, but who ultimately uses it to track down his fellow classmates to make amends over past wrongs, and the protagonist Shuya Nanahara, whose only motivation is the protect his friend Noriko, determined not to lose anybody else after his father’s suicide and the murder of his best friend at the beginning of the film. These students are not angels, nor are they “tragically flawed” in the half-assed way slasher films make their characters to justify their deaths; they’re teenagers, hormonal and exuberant and forced to murder one another so that the adults can keep their society the way it is.

The killing, of course, is metaphorical; we can’t simply allow all these teenagers to waltz into adulthood, they’re not prepared! Adulthood is a brutal exercise in Social Darwinism, where only brute strength and cunning can be relied on for survival. But even if the forces that be in Battle Royale use this idea as a theoretical justification for their systems of domination, the practice is much different; rather than work communally towards mutual survival, the students of Class 3-B are forced to kill each other, or else be killed by their detonating collars. The artificial conditions of the Battle Royale parallel the artificial conditions of the world that created it; a system of exploitation, a neoliberalism that always reproduces conditions of deficiency and inequality so that it may continuously justify its own existence. Not enough wealth, not enough resources? Let the free market take care of it! It’ll find a place for everyone and everything. Except when it doesn’t, as is the case in capitalist crises and the system must find new means of justifying the accumulation of capital at the top at the expense of everybody else. In the case of first world countries like Japan, this usually entails an assault on a middle class anxious about their own socioeconomic status. By ensuring the middle class, and in particular the youth of that class, must cull their own numbers (quite literally) to ensure its own survival, the ruling class stays on top; while the students must kill one another, the teachers idle their time away.

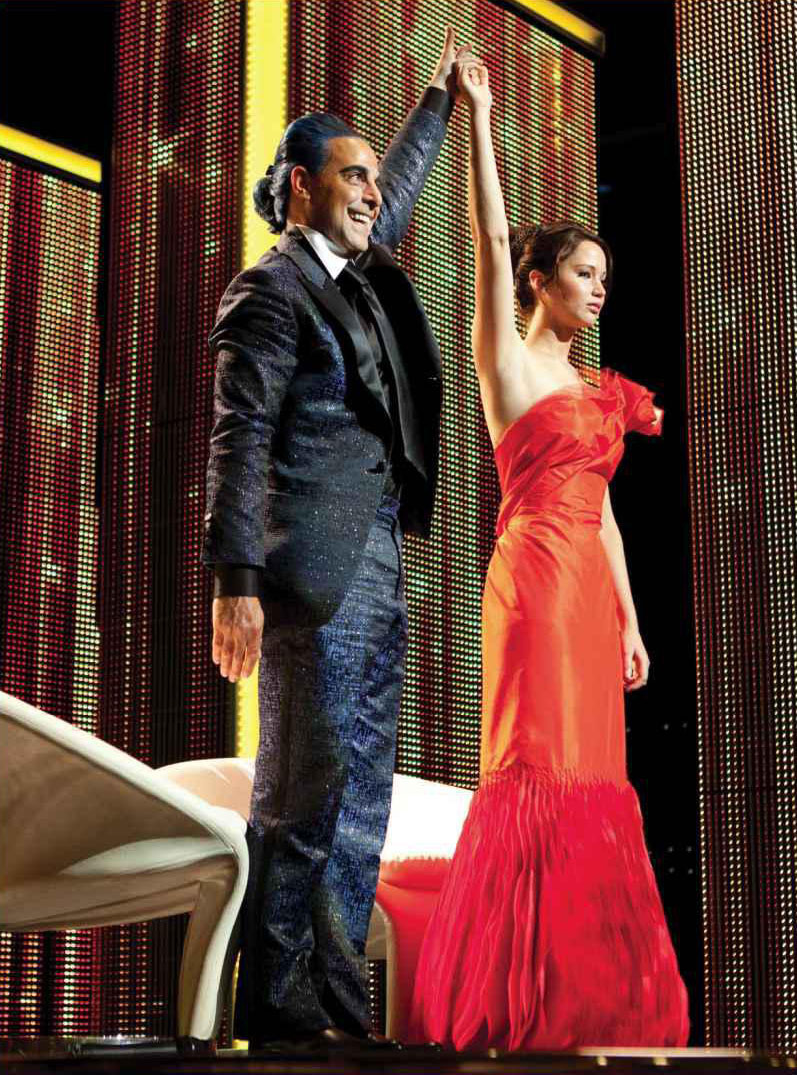

The notion of class is taken a step further in the most famous American manifestation of this genre, The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins. In the book and film, two children from each of the twelve outlying Districts of the nation of Panem (a dystopian, post-nuclear America because we’ve never heard that one) are forced to fight to the death as a means of paying tribute to the Capitol, as penance for a civil war waged 74 some-odd years ago. The very name of the nation references its predication on inequality; the tribute the districts pay, called the Hunger Games, are a form of Panem et Circenses, bread and circuses built on the back of the lower class for the enjoyment of the higher ups. And just to keep future generations from ever questioning their position, the Capitol makes sure to keep them busy and divided by making the Games into a public, much spectacle and a means for any given District to win glory (and much needed food) for themselves.

While Battle Royale shifts panoramically across different characters and storylines, Hunger Games focuses on one character, Katniss Everdeen, a girl from the lowliest beginnings who volunteers to participate as a means of saving her little sister who is originally chosen. In her own way, Katniss represents a contemporary conception of the American dream; throughout the games, she manages to succeed not by brute force or cunning, but by being charismatic and resourceful, kind to her allies and smarter than her opponents. When she’s in danger, she is often saved by others (like Peeta, a boy enamored with her, and Thresh, who does so as part of a blood debt), and when she kills, it is only to survive or out of righteous fury, as when her friend Rue dies. Ultimately, her actions begin to sow the seeds for open revolt throughout the nation, and when it comes down to her and Peeta as the final two survivors, she chooses to take her own life alongside him, forcing the Capitol to call of the games and name them both winners.

If one continues reading the Hunger Games series, they’ll see it ultimately plays out in a similar style to Battle Royale; the system of domination and exploitation, targeted primarily at young people but also at the middle and working classes in general, cannot be defended or sustained, and must be subverted and overthrown so that the cycle of violence may end. But in the course of the killing spectacle itself, the characters of Battle Royale are often fleshed out, developed, made into believable human beings and then killed, while in Hunger Games, Katniss seems to survive without ever having to truly compromise her ethical values, the other characters either acting as shields or protectors of her. In Katniss, we see a character who manages to survive by doing just the right things at just the right time, succeeding with cleverness and just a bit of luck. In Battle Royale, the protagonists Shuya and Noriko only manage to survive when one of the teachers ultimately lets them, motivated by a combination of pity and obsession. While in Hunger Games, there is the suggestion that success in a system of domination, even a conditional, unstable success, is still attainable, still within the grasp of the most adept and resourceful regardless of status, Battle Royale maintains no such hope, acknowledging that ultimately it is only through connections and social status that one can survive.

Fans of both Hunger Games and Battle Royale vociferously argue that the two works are completely different, and to an extent I agree with them. For while both share a similar premise, one grounded in an understanding of systems of oppression as well as an anxiety regarding recession, the decline of the first world, and the long “crisis of capitalism” that has been ongoing from the end of the 20th century to the 21st, they ultimately approach their own metaphorical models in different ways. In Battle Royale, we find little reason to hope for anything but full overthrow of the system at hand, while Hunger Games seems to suggest there might still be hope for success. But even if we accept the intimations in Hunger Games and agree that even the lowliest and meanest among us can rise to greatness, what of the remaining tributes killed? Were they not resourceful, kind and determined like Katniss, with their own backstories and hopes and dreams? We never get to know, as the majority function either as allies dedicated to Katniss, evil enemies determined to kill her, or nameless, faceless casualties we never know anything about. For the Hunger Games narrative to work, we must believe in the power of the individual to overcome, even if this requires one individual being prioritized above all others. In Battle Royale, such a gesture is futile.

Is this difference in attitude towards the system a reflection of the mindsets within their respective countries of origin? In Japan, the economic recession has been an ongoing crisis for more than 2 decades, while we here in the States know it as a largely new phenomenon. In Hunger Games, we can still see the potential for success in a rigged system, however fleeting; in Battle Royale, there is an overwhelming sense of resignation, a sense that if we cannot escape the system of domination, we must enjoy it or seek to destroy it. And on the topic of enjoyment it should be noted that as a film, Battle Royale is far gorier than Hunger Games. W hile Hunger Games actively attempts to distance the viewer from scenes of gratuitous violence, Battle Royale revels in them and even sexualizes them, titillating the viewer with a spectacle they ought to otherwise be horrified by. While Hunger Games takes a principled stand against the violence, Battle Royale submits to it, even enjoys it.

So what can be said of this nascent genre? Is it political, or decadent? Should it enjoy its own violent spectacle, or take a principled stand against it? Will it become the new “zombie film” of pop culture? God let’s hope not. Although I haven’t read much of Avenger’s Arena, where it ultimately takes the genre will be most telling; it could go down the Battle Royale route, positioning itself along the lines of horror films in saying that hey, if we can’t escape the violence, we might as enjoy it, or the Hunger Games route of keeping one’s chin high even in the direst of circumstances. Neither approach is perfect, each has its merit; while Hunger Games refuses to revel in the spectacle of violence or enjoy it, Battle Royale shows that the only way you can hope to beat a system of exploitation is to resist it with everything you’ve got. Avenger’s Arena has the potential to push the genre in one of two directions; towards gory, ideologically hollow exploitation, or towards a political attack on the ways in which youth are brutalized, sexualized and forced to fight one another in media and society, a critique especially salient in this age of precariatism, unpaid internships and the never-ending recession. Either way, as long as it keeps being fun to watch and continues giving grown-ups the middle finger, it will find an eager audience amongst adolescents and young people alike. Whether it will be pure entertainment or motivation towards some greater, more nebulous and worthwhile goal, remains to be seen.