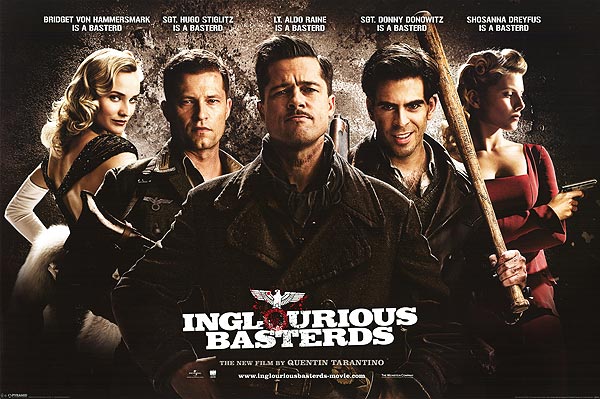

Last week I had a piece at Salon where I talked about fascism and the aestheticization of politics in Dead Poets Society. I’d originally intended to talk about Inglorious Basterds as well…but I ran out of space. So I thought I’d try to do it here.

Just to recap: the aestheticization of the political is a phrase coined by Walter Benjamin to describe one of the characteristics of fascism. Quoting trusty Wikipedia, “In this theory, life and the affairs of living are conceived of as innately artistic, and related to as such politically. Politics are in turn viewed as artistic, and structured like an art form which reciprocates the artistic conception of life being seen as art.” So fascism treats political issues as the occasion for pageantry ; differences in power or goals are all subsumed into symbolic unities — like the Nazi arm band or the mass meeting — or symbolic marginalization — like the scapegoating of Jews and blacks.

Inglorious Basterds is, like all of Quentin Tarantino’s films, so kinetic and pulpy that you don’t necessarily think of it as particularly thoughtful, about fascism or anything else. In fact, though, Tarantino seems almost to have made the movie specifically to illustrate Benjamin’s argument. The Nazi’s in Basterds are obsessed with image and aestheticization. The first scenes of Martin Wutke’s ridiciulously mugging Hitler, for example, are set against a backdrop of an artist working on a large, hyperbolically noble wall painting of the dictator. More, the Nazis in the film are presented as being obsessed with Nazis in film. The plot centers on a screening of a re-enactment of a German war triumph in which the hero, Private Zoller, plays himself. At the direction of propaganda minister Goebbels, Zoller the hero becomes Zoller the icon — a politicized propaganda image of himself. That image is so important that Hitler himself comes to the screening, giggling happily (like Tarantino himself?) as screen Zoller shoots dozens of men. Hitler compliments Goebbels enthusiastically on the screen carnage, at which Goebbels almost breaks down in tears — a propagandist who believes in his own imagined Fuhrer.

You could say that the aestheticization of politics dooms the Nazi’s in the film; they’re so obsessed with the propaganda image they’re creating that all of the Nazi brass decide to attend the opening of Zoller’s film, exposing themselves to not one, but several murderous plots. The image of Nazi victory turns into the reality of Nazi defeat — Zoller himself is shot by a French Jewish plotter even as his film self (played by his real self) kills enemy soldier after enemy soldier onscreen. And we get to see Hitler riddled with bullets by Jewish-American soldiers, doomed by his love of (his own) image.

Of course, Hitler wasn’t really killed by a Jewish-American soldier in a movie theater. That’s just a filmed fantasy of victory — a Western mirror image of the Zoller film. Hitler sits himself down to see an iconic, aestheticized encapsulation of his political prejudices, and we do exactly the same thing. Tarantino positions us, watching the Nazis die, in the same place as the Nazis watching their enemies die.

If the Nazis aestheticize the political, in other words, then so does Tarantino, and so, in the same way, do we watching Tarantino’s film. Inglorious Basterds is one suspense tour de force after another, with larger than life characters pirouetting virtuosically through breathtaking set pieces, punctuated with knowing flash-backs, ironic voice overs, and compulsive references to films, films, films, from spaghetti westerns to Triumph of the Will. The violence, the plotting, the revenge narrative and the sheer spectacle are so overwhelming and delightful that the occasional nos to political content is actually jarring. When Jew-Hunter Hans Landa (Christoph Waltz) makes an offhand remark about how he can “think like a Jew,” and compares Jews to rats, it seems gauche, unnecessary. He’s just supposed to order that family shot in a blaze of choreographed violence; linking the bloodbath to some sort of ideological meaning seems wrong.

The implication here is that, in important ways, Western democracy isn’t all that much different than fascism. The politics of both are couched in aestheticized symbols and mass ideology as spectacle. Brad Pitt’s murderous American guerilla Aldo Raine operates on much the same principles as his Nazi enemies; just as they see the Jews as a species, so he sees them as subhuman, marked. As he says, the idea that a Nazi soldier might go home, take off his uniform, and return to civilian life is wrong and inconceivable. A Nazi is always a Nazi, and so Aldo carves a swastika onto the foreheads of his prisoners, to make sure that the categorical difference he sees, the clear division of the races, will remain symbolically visible — political demarkations given aesthetic form. (It’s worth noting too that Aldo is nicknamed the “Apache” for his habit of taking scalps. Tarantino may well be aware aware that the American Indian genocide was a direct source of inspiration for Hitler’s Holocaust.)

The last image of the film is Aldo and an associate looking out of the screen, supposedly at the swastika Aldo has just carved in Landa’s head. “I think this just might be my masterpiece,” Aldo says. It’s a self-reference; Aldo is a stand-in for Tarantino, who completes his film about Nazis at the same time as Aldo completes his Nazi symbol. But Aldo’s self-satisfied smirk is also (self-)deceptive. The Nazi here is not going to remain a Nazi; as soon as the film ends, in fact, Landa will go back to being Christoph Waltz, who (thankfully) has no swastika carved into his skull. Aldo’s dream of Nazis who are forever Nazi, like Tarantino’s dream of Hitler killed in a movie theater — they’re both just aesthetic fictions. Politics as symbol ultimately fails.

It’s true that part of the giddy rush of Inglorious Basterds is the sense that art can be politics; that we can make Jews take their revenge on Hitler just by representing it as truth. But part of the film’s power is also, contradictorily, the refusal of aestheticization; the insistent artificiality and theatricality remind you that the politics here are aesthetics, and so never allow the first to be subsumed by the second. Aldo can’t really reach out of the film and draw the swastika on our head. The symbol he wants to be totalizing isn’t — which means, maybe, that these bloody fantasies don’t have to control us forever. The real hope of Basterds isn’t that the Nazis will get theirs, but that, maybe, we can take off that uniform, and leave the theater.