Hagrid’s half-Giant identity is a plot arc in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, so too are the House Elves and Hermione’s crusading, if not paternalistic, attempts to free them from oppression. In the Deathly Hallows the penultimate “other” becomes the mudblood, a term we first hear in Chamber of Secrets. The final book, too, revolves around non-wizarding creatures of, as the Ministry of Magic and Dolores Umbridge put it, “near human intelligence,” and Harry is labelled as a very odd, special, and different wizard by Griphook the Goblin because he treats non-humans with courtesy and respect. The books are dedicated to highlighting the fallacy of “the other” but, and file this under uncomfortable truths, all the human characters of colour are relegated to the sidelines.

JK Rowling has called her books “very British” in a number of interviews, and has even stated that they are a “prolonged argument for tolerance.” However, I can’t help but draw parallels (note: I’m drawing parallels, not determining causality) from her treatment of race and “otherness” in the books to the conversations about multiculturalism and race theory that have occurred throughout British history and continue today.

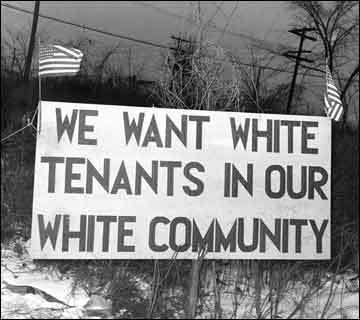

Rowling has been very explicit about the connection between Pure Blood Wizarding ideology and the Nazism that led to the holocaust. But race theory, the belief that attributes and abilities could be determined by the socially constructed notion of race, was equally dominant in the United Kingdom. Weeding out “undesirables” wasn’t particular to Nazi ideology and was common across Europe.

British identity was partially constructed using internal colonization, where Welsh, Scottish and Irish minorities were subsumed into Britishness, an identity which still remains ambivalent and dynamic. Britishness was also constructed in opposition to a number of external European threats and was only reinforced through colonialism, which was justified by applying race theory.

Even after the Second World War, Great Britain restricted entry to Jewish refugees while simultaneously citing its own tolerance. Jewish bodies were and continue to be racialized, but even though Rowling has been explicit with her works’ connection to the Holocaust, racism is constructed as pureblood witches and wizards versus muggles, mudbloods, and magical creatures.

I’m not the first person to note that the fantasy genre has a history of replacing PoCs with monsters and magical creatures. Writing for Fantasy Book Review, author Lane Heymont states:

…[I]t feels like white authors have an easier time, or are more comfortable, writing from the perspective of dragons, ghosts, elves, Minotaurs, and other non-humans than another human being. Seems ironically odd, don’t you think? And the writing suffers for it, as does the cause.

I target fantasy specifically because I know that Rowling has the ability to write from a PoC’s perspective as evidenced in The Casual Vacancy, but her fantasy works imitate most of the genre: There’s a brilliant ability to create non-human cultures and magic systems, but fantasy novels with people of colour as main characters are sadly rare.

If these books are “very British” and the quintessential “others” in British society are racialized minorities, than why has race been rendered invisible? Whether intentionally or not, side-lining characters of colour matches the British multicultural model that defines racial integration as near invisibility.

Racialiazing “otherness” has been part of the British experience, and Rowling, with her progressive roots, seems to be reacting towards this kind of cruelty by dedicating seven books and several years of her life to combatting it, only to create works that replicate the systemic exclusion of minorities. To clear up any confusion, I’m not saying that Rowling had to talk about how it feels like to be black at Hogwarts, but what it feels like to be Dean Thomas at Hogwarts. (Incidentally, I was disappointed that while Thomas’ backstory was potentially up for inclusion in the official cannon, it eventually had to be axed due to editorial limitations. I look forward to reading more about him in Pottermore.)

As a series that practically begs the reader to take it personally and that has birthed devoted communities and fan conventions, issues of representation and inclusion become incredibly important: fans want to know that they’re allowed in, and if you’re aiming for an emotional reader response, then this is a reaction that should be taken seriously. Further, the exclusion of active people of colour in fiction constitutes a form of erasure that undervalues their construction of and contributions to both fictional and real societies.

As it stands, we know that Hogwarts plays host to a variety of people of colour (Cho Chang, the Patel sisters, Dean Thomas, Blaise Zabini, Kinglsey Shacklebolt etc.) but they are, in a sense, rendered invisible. Their races are so invisible, in fact, that they’ve become model minorities; their races do not detract from their Britishness.

The idea of integration as a key to a successful multicultural policy stems back to the Second World War. British politicians knew, especially after Kristallnacht, what Germany’s Jews were facing, but still worked actively to limit the number of entries into the country. In 1965, Roy Hattersley, a Labour politician argued that “without integration, limitation is inexcusable, without limitation, integration is impossible,” the idea being that immigration should be restricted because it might rile the emotions of British citizens, the same rational for restricting entry to Jewish refugees. Minorities became responsible for the resentment directed towards them.

The subtle casuistry of this linkage of a commitment to “harmonious community relations” to necessary restriction on immigration and immigrants has continued to be employed by successive British governments. It has a wonderfully corrupt, but popularly acceptable rhetorical formula which argues that:

- as decent and tolerant people we are naturally opposed to any form of racism or discrimination.

- simultaneously, we are committed to a harmonious society.

- however; immigrants and ethnic minorities have a capacity to generate racial hostility and discrimination from the majority population.

- consequently: in order to guarantee harmonious community relations we must rigorously control immigration.

–Charles Husband, Doing Good by Stealth, Whilst Flirting with Racism: Some Contradictory Dynamics of British Multiculturalism

More recently, government officials stated that the reason the London Bombers carried out the 2005 train attacks was because they were insufficiently integrated into British culture, even though the evidence pointed otherwise, thus starting a firm government push to ensure that Britain’s Muslims were also “well-integrated.”

In 2003, in response to the Labour government’s proposed legislation on asylum seekers, British tabloids exploded with accusations that immigrants were abusing the system and dirtying the country with AIDS, Hepatitis B, and TB. These accusations don’t seem so far off from the hearings held in the Ministry of Magic, where we saw a witch being accused of stealing a wand (stealing from the system) and not being sufficiently magical (British.) While Rowling’s stories may have been inspired by the holocaust, they still play out in Great Britain today. They are indeed “very British” books; Rowling is both prescient and astute when she highlights government and media sanctioned oppression and she’s at her strongest when she writes these scenes.

Only last week The Guardian published a piece by David Goodhart, who accused liberals of favouring a highly-individualistic identity that transcended the boundaries created by the nation state, roughly defining certain liberals as being pro-immigration and therefore anti-community.

This individualistic view of society makes it hard for modern liberals to understand why people object to their communities being changed too rapidly by mass immigration – and what is not understood is easily painted as irrational or racist…If society is just a random collection of individuals, what is there to integrate into? In liberal societies, of course, immigrants do not have to completely abandon their own traditions, but there is such a thing as society, and if newcomers do not make some effort to join in it is harder for existing citizens to see them as part of the “imagined community”. When that happens it weakens the bonds of solidarity and in the long run erodes the “emotional citizenship” required to sustain welfare states.

According to Goodhart, the very presence of immigrants destabilizes allegedly harmonious British communities with resentment (a romanticized fallacy, especially when looking at Britain’s long history of class warfare), their bodies becoming symbols of chaos that disrupt a cohesive national identity. To be a racialized minority is to have people assume that you are unwilling to emotionally integrate into British identity and society. Some conservatives argue that under multiculturalism people will abdicate working together towards a common collective goal known as nation-building; however, the examples above show that Britain’s ideal form of multiculturalism has always been assimilationist.

Rowling is progressive, clearly pro-immigration, and the Harry Potter series illustrate a typical liberal approach to race blindness. Her works still presuppose that integration is synonymous with invisibility, but she also argues for the potential success of Britain’s multicultural model. Their well-integrated and invisible races ensure that Cho Chang, Dean Thomas, and the Patel sisters can be British without disrupting British identity with their racialized bodies. While I appreciated that Cho Chang became a sobbing mess in Order of the Phoenix without her emotional deterioration being tied to her ethnicity, I can’t separate issues of representation from the larger systemic trend found within the fantasy genre. (Cho is the character of colour with the most screen time. One chapter is dedicated to her character in Order of the Phoenix, where she spends most of the time crying, and she receives a few sentences here and there from books 4 to 7. When we meet her, in book 3, she doesn’t say much of anything.) That characters of colour are in the background allow the reader to know that Hogwarts is Very Diverse, but their importance to the plot is minimal. As the very worst possibility, they act as ornaments to Hogwarts’ status as a Very Progressive School.

This integration-as-invisibility approach is distinctly different from the movie adaptations, where the characters of colour wore clothing representative of their ethnic backgrounds to the Yule Ball, whereas the same characters in the books wore dress robes like everyone else. Except…children of immigrants don’t uniformly wear clothing from their parents’ home country. While the Potter books erase ethnic difference, the movies champion essentialism which, to her credit, Rowling can’t be accused of doing.

Rowling spends seven books opining about the importance of diversity, while replicating the systemic sidelining of characters of colour. The characters in the Harry Potters books are proof of multiculturalism’s success, but the structure of the books imitate systematic issues concerning racial representation. There’s tension in this approach: on one hand, it becomes exhausting to have one’s entire identity defined by ethnic background (something we can’t choose) and being able to choose one’s identity through acquired membership (identity markers we can choose, eg. being part of an SF/F fandom) can be a highly liberating experience. On the other hand, if Rowling believes in anti-otherizing, then why isn’t the quintessential British “other” given more screen time, not to discuss race, but to simply be? While a British progressive may envision a rainbow utopia of immigrants and new citizens, we know that their invisibility exists to comfort us while we pat ourselves on the back for being progressive. When it comes to screen time for characters of colour, their stories are still marginalized. The Harry Potter books are in no way the worst offenders in the genre—and I still remain a loyal fan—but there’s a serious cognitive dissonance that needs to be analyzed when a book series extolling the virtues of diversity are not particularly diverse themselves.