Ha ha, no, that title’s just clickbait

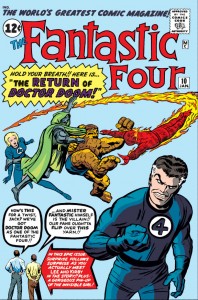

Jack Kirby and the Visual Logic of Superheroes

Part 2: Bif bam pow etc.

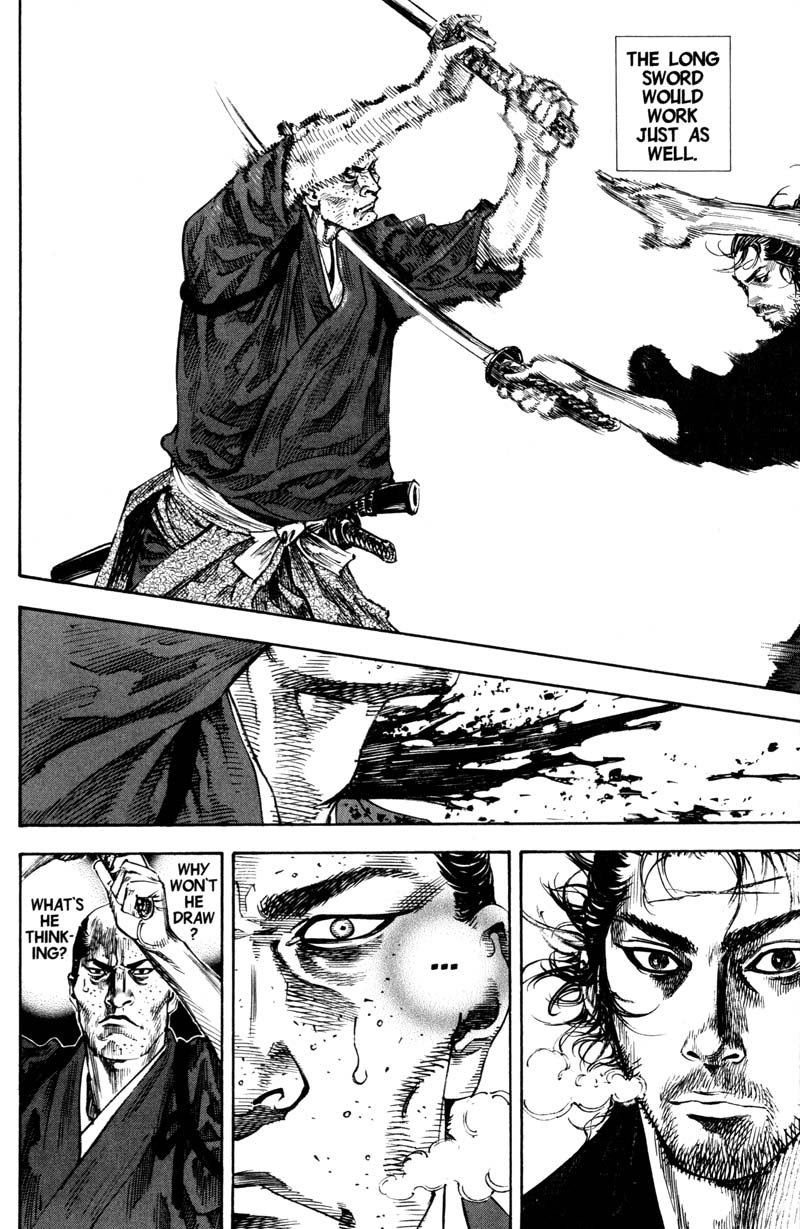

In Part 1, I talked about the fundamental structure of a fight scene. To recap, a fight scene is

a sequence of events caused by the aggressive and defensive (and other) actions of two or more combatants

To which the only sensible response can be: duh.

In this second part, I was going to get to Kirby, but that’s going to have to wait until Part 3. Here, I’m going to talk about how the demands of the fight scene constrain the imaginative space of superhero comics. So, a question: how many possible superpowers are there, and how many actual superpowers have appeared in comics?

To answer this, we first need to have a rough understanding of what makes a superpower, so:

a superpower is an agent’s ability which is (either explicitly or implicitly) the product of some non-natural cause

By “non-natural cause”, I mean some cause which either isn’t recognised by current science or is beyond current technological capability. That pretty much covers it, I think: Dr Strange uses magic to fly around and zap folks, the Hulk’s strength is caused by gamma rays, Thor is a god, Iron Man uses advanced technology, Spider-Man gets bitten by a radioactive spider and also invents his own advanced technology in the form of webbing, the Fantastic Four are transformed by cosmic rays, etc.

All right, so how many possible superpowers are there? Answer: infinitely many.

Let’s just start with one of the superpowers just mentioned — the Hulk’s superhuman strength. The Hulk is strong. Like, really, really strong. His strength is linked to how angry he is; the angrier he gets, the stronger. Various Marvel comics have even suggested that his strength is practically limitless (on the assumption that so is his anger). So that’s one superpower from one character.

Here’s another superpower, from a character that I just invented: he’s called the Thulk, and he’s just like the Hulk except that he only has superhuman strength on Thursdays.

Here’s another guy: the Wulk, who only has superhuman strength on Wednesdays.

Here’s another: the Fwulk, who only has superhuman strength on every fifth Wednesday.

And another: the Cfwulk, who only has superhuman strength on every fifth Wednesday, providing it was a crescent moon six nights ago.

And one more: the Rcfwulk, who only has superhuman strength on every fifth Wednesday, providing it was a crescent moon six nights ago, and the current US President is a Republican who has never eaten haloumi cheese.

Or we could generate possible superpowers a different way:

The Rulk, who has superhuman strength only when fighting Republicans

The Chulk, who has superhuman strength only when fighting chickens

The Dchulk, who has superhuman strength only when fighting chickens that are disco-dancing

I could go on all day, but you get the picture. We can generate infinitely many superpowers using just the idea of superhuman strength as our starting point. But most of these superpowers are also trivial and, well, silly. As a character, Rcwfulk probably has less storytelling potential than his more famous counterpart; Rcfwulk stories would quickly become as predictable as an episode of Knightboat. Must defeat the evil plan of my arch-nemesis — but *choke* can I stop him before President Jeb Bush enters that cheese shop?!

So let’s try and open our minds in a different direction. The Doom Patrol of Grant Morrison and Richard Case (et al.) was one of the more outre superhero comics by a “mainstream” publisher, and featured plenty of offbeat powers. One of the more offbeat powers belonged to the Quiz, whose superpower was to have every superpower you haven’t thought of yet. Among her powers were the power to turn people into toilets filled with flowers, and to make escape-proof spirit jars, but presumably she could also rewrite the complete works of Pierre Menard, read the minds of radiator heaters, and transform into a fifty-foot giant J. Wimpy Wellington with the wisdom of Stephen Hawkings and the strength of Nicolas Sarkozy. The Quiz belonged to the Brotherhood of Dada, which also included (inter alia) Mister Nobody — who could only ever be seen in the corner of people’s eyes, Alias the Blur — who ate time, and (my own favourite) Number None — who, in the words of Mister Nobody was “the person who bumps into you when you’re late for the train; the chair that collapses underneath you when you’re trying to make a good impression on your girlfriend’s parents; that man who seems thin but somehow you can’t get past him because he takes up the whole sidewalk”.

The worlds of superheroes are worlds that operate by different causal laws than our own universe. Sometimes those worlds have super-science, sometimes they have magic, but they all have characters that can do things we cannot. They can, potentially, do anything — so why do so few superheroes have the range of powers shown by the Brotherhood of Dada?

Let’s take a look at some superhero comics Marvel and DC will be publishing in August — what superpowers do the protagonists in these comics have? (1)

***

Marvel

Nova — flies, shoots people with energy beams

Captain Marvel — flies, punches people, shoots people with energy beams

Superior Spider-Man — swings on webs, crawls on walls, punches people, shoots people with webs

Ultimate Spider-Man — ditto

Carnage — ditto, plus stabs people by changing his hands into knives

Venom — ditto, plus shoots people with normal guns

Scarlet Spider — as for the Spider-Men, plus burns people with his hands, stabs people with spikes in his arms

Morbius — flies (kind of), punches people, bites people, scratches people

Captain America — punches people, throws shield at people, sometimes shoots people

Thor — flies, punches people, hits people with hammer, throws hammer at people, shoots lightning at people, fails to understand really quite simple principles of middle-English speech

Iron Man — flies, punches people, shoots people with repulsor rays

Hulk — punches people

Punisher — shoots people, sometimes stabs or explodes them

Daredevil — actually has interesting powers, usually just punches people anyway

Hawkeye — shoots people with arrows

Wolverine — stabs people with claws

Gambit — throws playing cards at people

Deadpool — stabs people with swords, shoots people

Kick-Ass — I assume ironically fails to do so

***

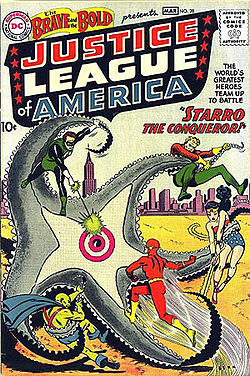

DC

Pandora — shoots people with magic guns

Phantom Stranger — does ill-defined magic stuff

Constantine — ditto

Aquaman — swims, punches people, stabs people with a trident

Green Arrow — take a guess

Katana — see if you can guess this one, too

Justice League of America’s Vibe — shoots people with vibrations

The Flash — runs fast

Wonder Woman — flies in invisible plane, punches people

Superman — flies, punches people, shoots people with laser beams that come out of his eyes

Supergirl — ditto

Superboy — ditto

Batman — flies in Batcopter and Batplane, drives Batmobile, super-detective, still spends a lot of time punching people and throwing bat-shaped boomerangs at them

Batgirl — similar to Batman

Catwoman — punches people, scratches people

Talon — too much effort for me to find out, but I’d guess it’s the same as Catwoman

Batwing — similar to Batman

Nightwing — similar to Batman

Green Lantern — flies, has magic ring that can theoretically create anything from magic green energy, usually just shoots people with energy beams

Larfleeze — ditto, but coloured orange instead of green

Jonah Hex — shoots people

Animal Man — various animal powers, often does not punch or bite or stab people with them

Swamp Thing — as for Animal Man, but replace “animal” with “plant”

***

What do we learn from this brief survey? Three things:

(a) I have too much time on my hands, and am borderline OCD.

(b) Unexpectedly, DC’s superheroes are somewhat less punching-and-stabbing focussed than Marvel’s.

Then again, perhaps this is not so surprising when you consider some of the respective superhero highlights of the period that ultimately defined their respective worlds for later decades, the period from the late 50s through the 60s that myopic superhero fans generally call the “Silver Age” (2). Marvel has Kirby and Ditko, whose characters spend a lot of time punching each other. By contrast, DC has the Swan/Boring/Schaffenberger Superman group, whose hero does almost no punching, but instead spends an awful lot of time pulling elaborate hoaxes, working through gimmicky set-ups, or otherwise using his goofier superpowers such as super-ventriloquism and super-breath (3); the Forte/Swan Legion of Superheroes, whose members include Matter-Eater Lad — he does exactly what it says on the tin; and Infantino’s Flash, who also spends little time punching or hitting, instead using his powers in creative, non-aggressive ways. Then there’s DC’s second or third-tier (in terms of quality if not sales) comics from the period — e.g. the Haney/Fradon Metamorpho, “Bob Kane’s” Batman, and the Fradon Aquaman — a character so proverbially lame that his current writer felt the need to directly address this lameness in his new series, and who was made EXTREME in the 90s by chopping off his hand and replacing it with a kind of hook/trident thing.

He used it primarily to stab people.

On the other hand, let’s remember that two of their current comic books are about characters named after what they hit people with, part of a noble tradition of how to name your comic book — cf. Iron Fist, Savage Sword of Conan, Sword of the Atom, 100 Bullets... The TV show based on Green Arrow even drops the “Green” and is just plain Arrow. This is really quite weird when you think about it — why not call your comic book Punch or Gun?

And, even granting that there are some superheroes at DC whose powers are not primarily punching, zapping, or shooting, it’s worth noting that those are still the powers for most of them. And the highlights of “Silver Age” DC did also include the Anderson/Infantino Adam Strange, the Kubert/Anderson Hawkman, and Kane’s Atom and Green Lantern, all of whom spent a lot of time hitting people. Not to mention Kubert’s and Heath’s war characters such as the Haunted Tank, Enemy Ace, Unknown Soldier and Sgt. Rock.(4)

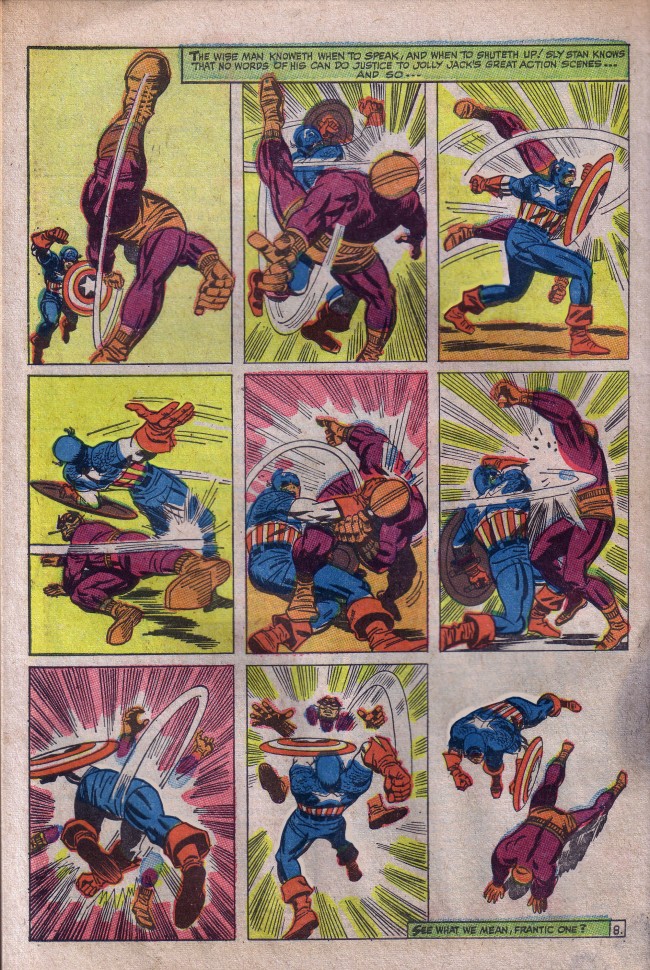

(c) Despite the theoretically infinite number of possible superpowers, the superpowers of most of the headlining characters are various ways to hit people. And if they’re not ways to hit people, they’re ways of not being hit, or not being hurt when they’re hit.

And this is just what we’d expect if we accept (the obvious fact) that the fight scene is the raison d’etre of superhero comics. For fight scenes, you need an Attacker who can

i) touch their opponent, in ways that

ii) hurt

and a Victim who can

iii) avoid being touched, and/or

iv) not be hurt

The vast majority of superheroes and supervillains have superpowers that fall into one of these four categories. And, generally, if they’re a superhero with their own comic book, they will have a combination of Attacker and Victim powers. If we take another quick look at the lists above, we generally have characters who, in addition to their attack powers, can also

- avoid being touched by Attackers’ attacks, as per (iii). One method is to have some kind of protective force that stops attacks from directly hitting you: Iron Man’s suit of armour, Captain America’s shield, the force fields of Green Lantern and Larfleeze. Another is to have some special way of not being touched at all: the Flash’s superspeed, the acrobatic skills of the Spider-Man and Batman characters.

- and/or not be harmed by attacks that would harm a normal human being, as per (iv). Many characters are just tough, impervious to even very powerful attacks: Thor, Superman, Hulk. Or they can recover quickly from attacks, with vastly accelerated healing, like Wolverine or Deadpool.

The fight scene determines everything in superhero comics, ultimately distilling all superpowers into two binaries: touching/not-touching and hurting/not-hurting. In the third, and final part of this essay, I’ll finally talk about how these two binaries dominate Kirby’s X-Men.

PS: No, fuck it, Thulk, Wulk, Fwulk, Cfwulk, Rcfwulk, Rulk, Chulk and Dchulk are the 8 greatest superheroes you’ve never heard of, copyright Jones, one of the Jones boys. Look for them soon in an upcoming series from Image Comics, where they’ll be, oh, let’s just say, retired assassins, or thieves who only steal from other thieves, or members of an age-old secret society, or spies for some marginally conceptually clever imaginary government agency. Image Comics: where basic-cable pitches come to die.

PPS: This was only going to be a two-part series, but I thought I’d ape contemporary “mainstream” comics themselves and not show the guy whose name is in the title until the very last moment, nor explain what he has to do with it all. In other words, Part 3 is just going to be a final splash-page of Kirby showing up in a dramatic pose.

(1) I’m only using comics with a single protagonist here, because it would take way more extra effort to figure out who’s who and what they can do in the comics with more than one protagonist (e.g. Avengers, X-Men, Justice League).

(2) I discussed two obvious problems with this classification schema here.

(3) Really, super-ventriloquism is used as a major plot-point way more often than you’d think.

(4) Oddly, Rock and Easy Company — a unit in WWII — do much more punching than shooting, presumably due to the strictures of the Comics Code. The diegetic justifications for this are generally pretty feeble, along the lines of “Those goose-steppers can’t open fire for fear of hitting their own men, so let’s get ’em, Easy!”.

Image Attribution: Fight-Man, by Evan Dorkin, image from comics.org. Fight-Man created by Evan Dorkin, owned now and until the end of the universe by Marvel Entertainment, LLC, a subsidiary of The Walt Disney Company.