(Spoiler alert: The endings of both the comic and movie are spoiled utterly and completely)

Films are quite often acts of misreading and miscommunication. The presence of fleshy humans and life-like movement have a tendency to lull audiences into passive acceptance, to turn metaphor into reality. If some people have enjoyed Bong Joon Ho’s adaptation of Jacques Lob and Jean-Marc Rochette’s Snowpiercer, it appears to be on the basis that it is an action movie with a few micrograms of grey cells ladled on top of it; those grey cells taking on concepts such as class and inequality, all somewhat lost in the shuffle of blood and bullets. In a sense, this seems an acceptable trade-off if only because I enjoy watching action movies.

The comic upon which the film is based is fragmented (possibly due to its roots in serialization in À suivre), almost meaningless in its connections, and has a Heavy Metal-style, Eurotrash obsession with naked women and whores. Yet it is intellectually more coherent and concerted in its purpose than the adaptation. The central device of a self-sustaining train (named Snowpiercer) as a metaphor for society is of course intact though Lob and Rochette’s description of it is impossibly large and thus purposefully absurd right from the onset. In both instances, the arctic apocalypse which has driven humanity to this mobile refugee camp appears to be man-made. Apart from this, there are other minor callbacks to the comic: there is the greenhouse carriage seen as a mini-wonderland within the close confines of the train; the glass observation cradle from which the protagonists view their metal world (reduced to a shootout in the film); and the sentient blob which is poked and sliced to produce food for the masses.

Bong has the money to feed his audience’s vicarious voyeurism, and the poverty and misery is laid on thick throughout his adaptation. There are fleeting glimpses of 20th century famines and assorted other tragedies. The (in)justice meted out in this hermetic society is medieval and the removal of body parts serve as compensation for sins committed—not an unfamiliar trope in Asian costume dramas. Their presence here reminds us that we live in an oligarchy if not an absolute monarchy. The minutes are filled with Tilda Swinton’s somewhat satisfying manic performance, as well as considerable forward momentum and violence. In the final reveal, the entrenched social hierarchy is seen to be the product of collusion between John Hurt and Ed Harris, the religious figures of the poorest and richest members of the locomotive. Perhaps a meditation on false consciousness and the complicity of the poor in their subjugation. Thus the film adaptation becomesan almost straightforward call for revolution. More, this particular revolution has a happy ending, one ignited with explosives which derail the train. Chris Evan’s pilgrimage to the front of the train is a success (though he does not survive it)—he is, in the end, a martyr, savior of children, and messiah. The survivors of the train wreck—a black Adam and Korean Eve—look out on to a barely hospitable winter landscape and life in the form of a polar bear. The world is saved; life will continue.

Strangely enough, Lob and Rochette’s comic hardly ever shows the degradation of the carriage slums, the final links in that chain of humanity. Most of it is communicated in words. We assume a multitude of deaths, cannibalism and what not. The decadence of the aristos is completely middle class and late 20th century Western Europe. They are ourselves and not distanced by the exaggerated efficiency of Tilda Swinton’s effete bureaucrat.

The protagonist, Proloff, is seen from the start in a carriage near “third class” being interrogated by soldiers who have caught him sneaking past his social station through a lavatory window (a meaningful escape). Adeline, his female appendage, is very much in the pre-feminist tradition of science fiction (see 1984’s Julia). She’s a social activist from third class hoping to alleviate the suffering of those crammed in the ghettoes of the nether carriages. She’s the innocent; the reader’s protective object and conscience; yet still possibly of more utility than her facsimile, Yona (Go Ah Sung), in Bong’s movie.

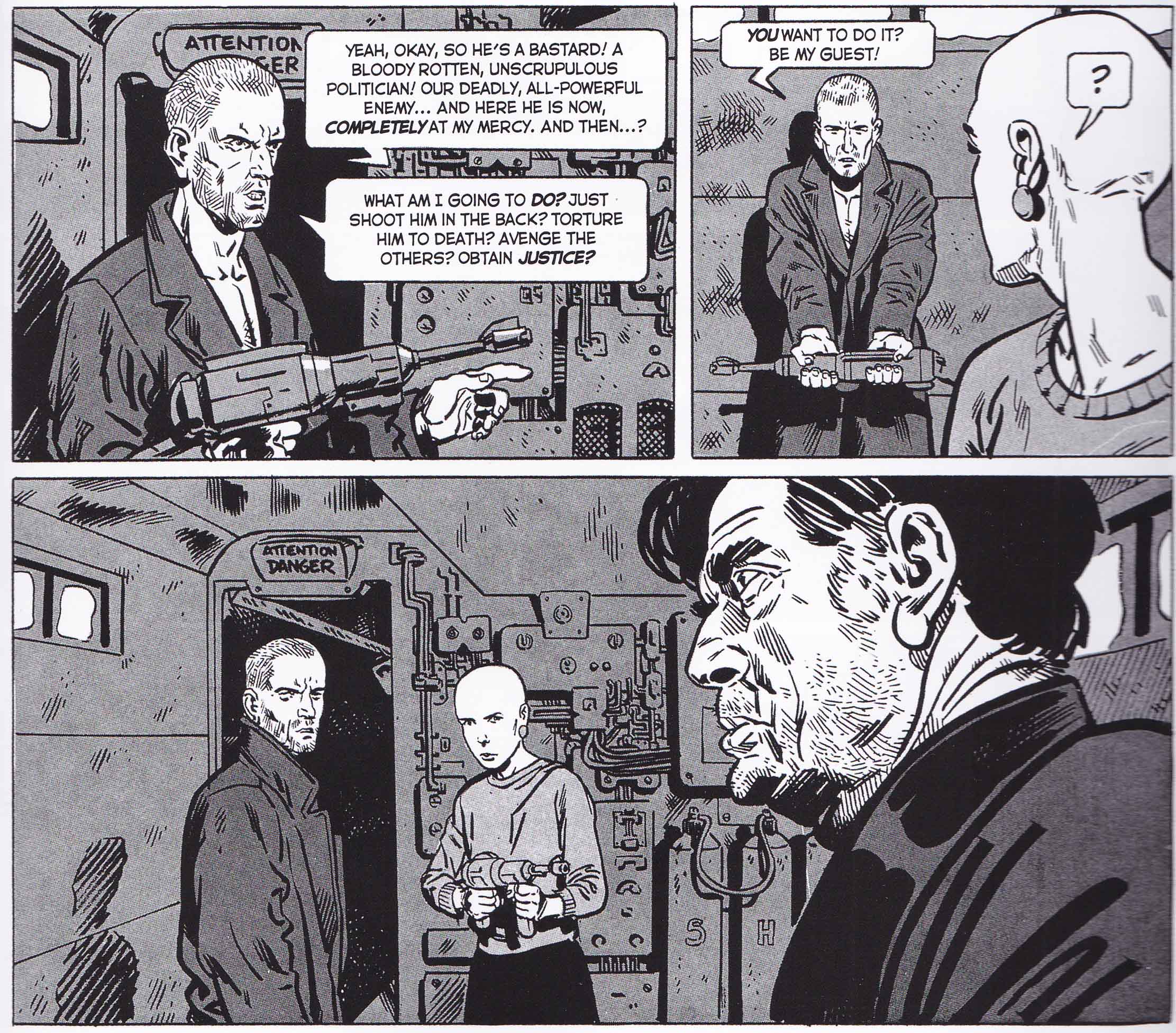

As with the film adaptation, Proloff also reaches the front of the train after a series of trials. The pair confront el Presidente who has hitherto been seen shouting orders to his henchmen down a microphone while monitoring the serfs on his mobile estate via closed-circuit television. But there is no comeuppance here; the President seems very much alive at the end of things. Proloff lets him go without any attempt at rectifying social injustices or enacting lethal vengeance. When Proloff offers his gun to Adeline, she turns around and refuses to do the same.

And since this is a comic very much in the French tradition, one assumes an implicit rejection of the values of that more famous revolution of 1789—no murderous rampage, no guillotine, no reign of terror, and certainly no cleansing Napoleonic wars. Then again, since the name of our protagonist has a Russian-Slavic ring to it, one might evince some connection to the Russian revolution of 1917 which ended with even more dead bodies than the French one. The links are purposefully uncertain—the cramped suffocating cabins of the comic and desperate crowds milling in front of the carriages certainly bring to mind Holocaust transportation; the shaven heads of our protagonists every form of concentration camp and gulag.

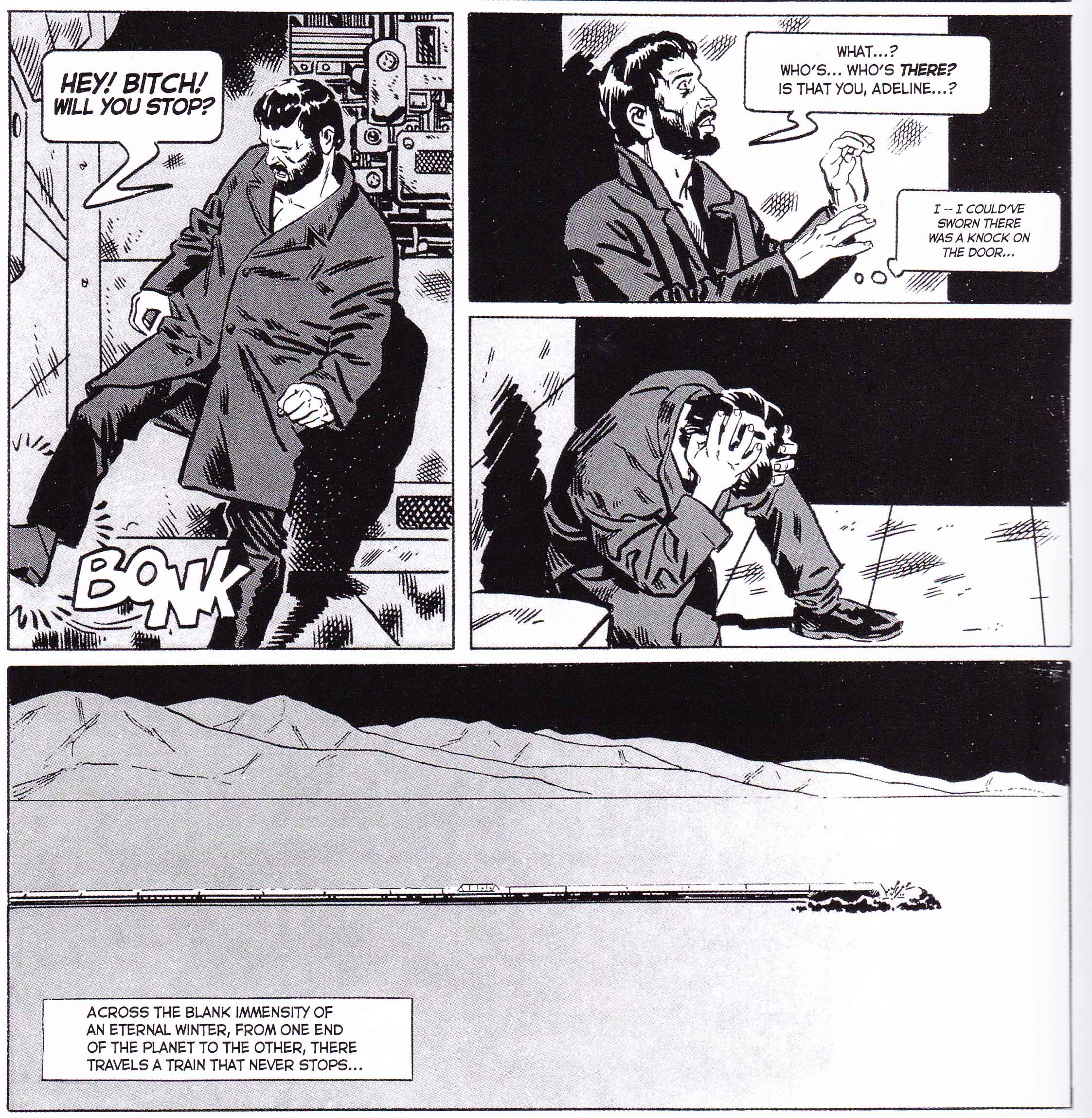

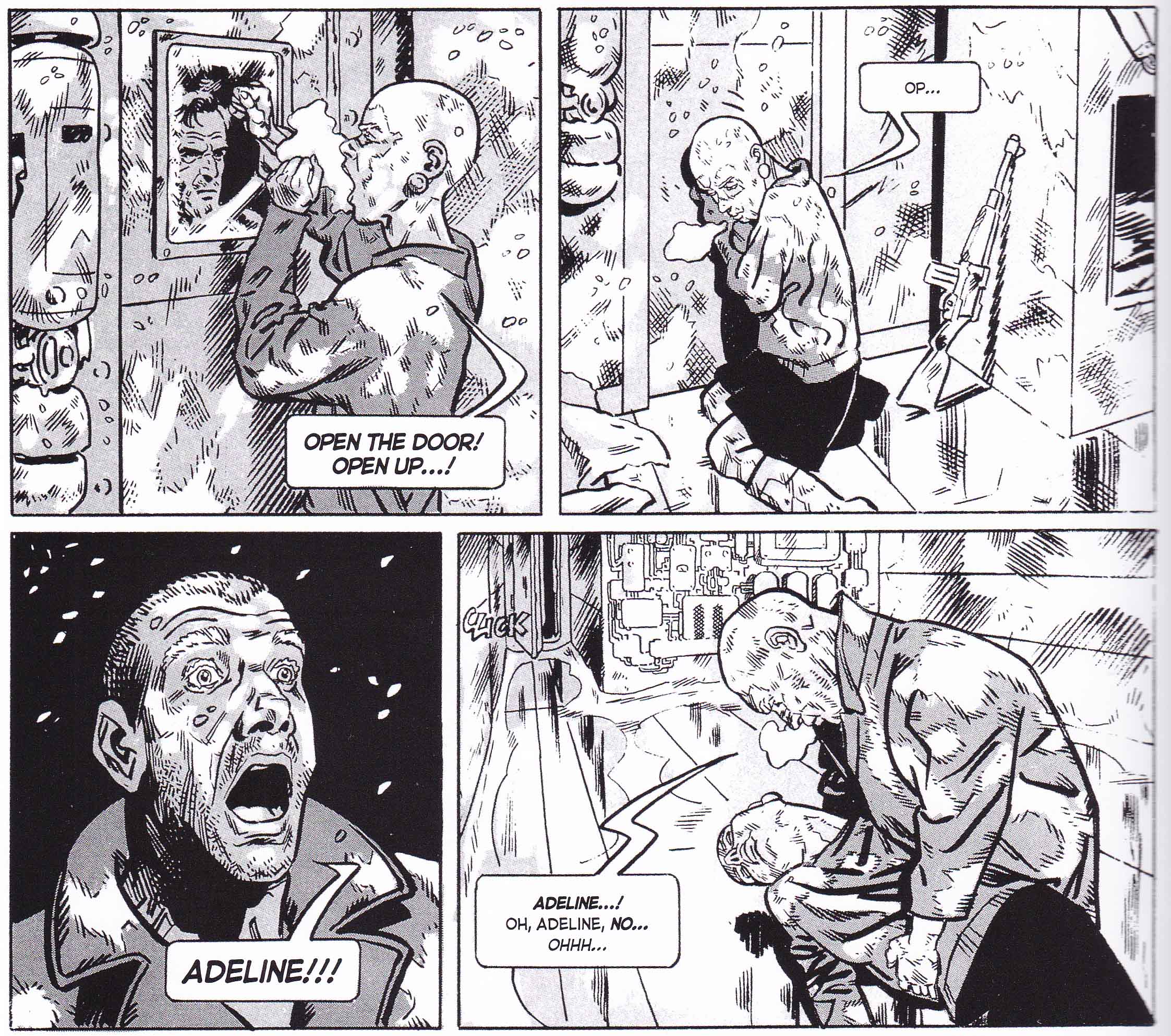

Proloff is characterized by his haphazard planning and inaction at critical junctures. In fact, his only act of volition in the closing pages of the comic is to shoot out the windows of the next to last carriage he has found himself in—the carriage just before the main engine room of Snowpiercer—thus condemning both Adeline and himself to a quick icy death; an act which he regrets almost immediately since he realizes that his nihilism isn’t shared by Adeline.

So dies Adeline—the Marianne of Lob’s tale—so dies idealism and reason. The winter which envelops her is not the welcoming, livable land of Bong Joon Ho’s film but quite incompatible with life. Proloff’s subconscious attempt at suicide is to no avail since he is saved by Alec Forrester, the father of the (near) perpetual motion engine which drives Snowpiercer, a haven which is periodically referred to by some cultists as Saint Loco.

The train is the universe in seemingly unending motion, yet gradually and imperceptibly losing its momentum—the Big Freeze beckons, all of space doomed to snuff out with the whimper of heat death.

“Across the blank immensity of an eternal winter, from one end of the planet to the other, there travels a train that never stops.”

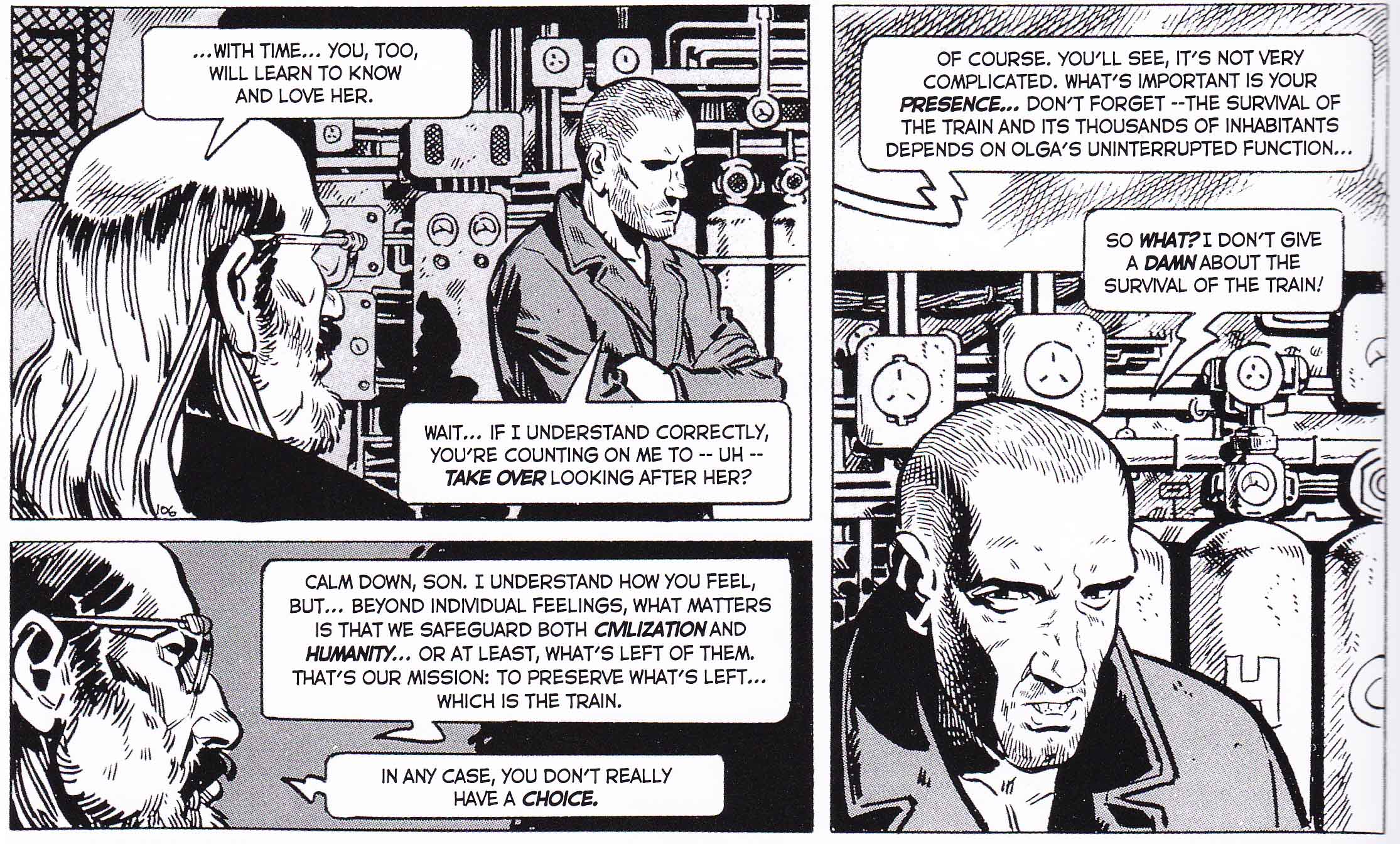

The aging engineer, Forrester, is a sickly but calm mad man. He is obsessed with the survival of the human race and civilization, yet so alienated from his fellow humans that all he desires is complete isolation—a misanthropic humanist. He may seem like a balding Ancient of Days but is anything but.

This is not to say that misanthropic humanism represents the highest ideal of our society, but it does appear to be the central driving force behind it (according to Lob). If anything, the engineer (this impetus) is depicted as an object of ridicule—a petty man behind the curtain, a diseased Wizard of Oz. The creator of the train is unnecessary for its running. He is the absent watchmaker voyeuristically spying on the train’s lesser beings, tirelessly speaking to a rumbling machine which makes no response.

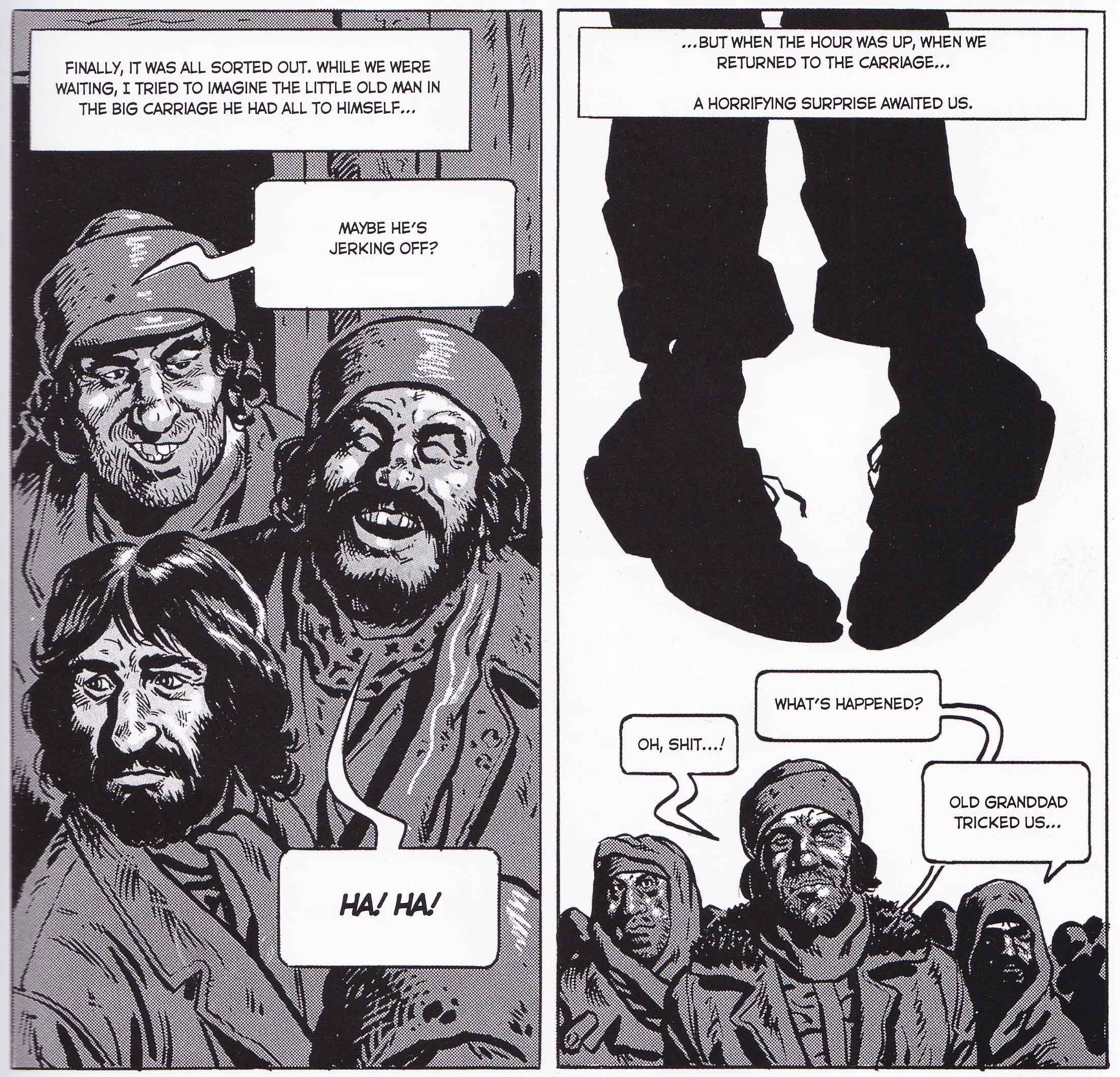

The train(s) keep on running but for no objective reason except the act of reproduction, occasional tenderness, and countless instances of inhumanity. This is the sum total of everything that has preceded this point in the story. Antinatalism would seem the obvious solution but is summarily rejected. The single memory which Proloff recounts to his interrogators at the start of the comic involves the act of providing a birthday present to a “sweet and quiet” old man “loved” by everybody. That gift is an hour of solitude which the man promptly uses to hang himself.

And that is probably the central motivation of Snowpiercer. Proloff’s entire journey to the “front” of the train (to the “front’ of society) is a quest for solitude to die with dignity, to kill himself in the luxurious confines of first class. As Varlam Shalamov writes in Kolyma Tales, “There are times when a man has to hurry so as not to lose his will to die.” In this allegory of life, the next to last carriage before meeting “God” has been christened death. The tragedy of Proloff’s tale is that even this simple extravagance is forbidden him. A similar kind of stoicism is found at the denouement of Max Ophul’s Lola Montes where Lola’s precipitous dive into an impossibly small tub does not lead to her death but a dull, humiliating existence; a kind of unwanted life after death.

At the close of the comic, a mysterious plague is carrying all before it from the back end of the train; its source unknown, possibly disseminated by Proloff himself, his nihilism reeking havoc on everything he touches. Only Proloff’s isolation from the mass of humanity protects him from its effects. He has “lost his right of residence in the universe” (Peter Zapffe) and in solitude waits out the end; not the last Messiah, just the last man.

__________

“…he feels the looming of madness and wants to find death before losing even such ability. But as he stands before imminent death, he grasps its nature also, and the cosmic import of the step to come. His creative imagination constructs new, fearful prospects behind the curtain of death, and he sees that even there is no sanctuary found. And now he can discern the outline of his biologico-cosmic terms: He is the universe’s helpless captive, kept to fall into nameless possibilities.”

The Last Messiah, Peter Wessel Zapffe