As a belated acknowledgement of Martin Luther King day, I thought I’d reprint this piece. It first appeared in (I think) 2007 in The Chicago Reader.

______________

A couple years ago the city’s One Book, One Chicago program encouraged Chicagoans to read Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird. Those that did encountered a familiar portrait of American racism, which, as we all know, was a problem mostly in the south, mostly in the past, and mostly perpetrated by poor, uneducated white folk. The novel’s hero, Atticus Finch, is a respected white attorney in a small Georgia town who defends a black man falsely accused of rape. At the end we’re assured that most people are pretty nice once you get to know them, and left with a vague sense that the world will keep on getting more and more enlightened as long as high school students continue to read high-minded novels like this one.

As a corrective to this lyrical vision of race relations, the city should consider endorsing Sundown Towns, a new study by James Loewen, author of the best-selling Lies My Teacher Told Me, that methodically upends many of white America’s preconceived notions about race.

Sundown towns were incorporated areas that banned African-Americans from living in them, or even from staying overnight. Often, a sundown town would hang a sign or signs at the city limits declaring, “Nigger, Don’t Let the Sun Go Down on You in ________.” African-Americans who were on the city streets after dark might be harassed, beaten, or worse. Even black people on public transportation weren’t safe: whites in Pana, Illinois, are reported to have fired gunshots at African-American Pullman porters as trains passed through town.

Sundown towns aren’t exactly unknown in popular culture; William Burroughs, Maya Angelou, and Tennessee Williams all mention them. But Loewen’s book is the first systematic exploration of the phenomenon, and while the existence of such towns isn’t a shock, virtually everything else he’s found out might be. Sundown towns, he discovered, were located mostly in the west and midwest, not the south. They came into being relatively recently, mostly between 1890 and 1930, but some as late as the 1950s–and Loewen was able to confirm the existence of towns that threatened African-Americans after dark as recently as 2002. Anna, Illinois, population 5,136, is likely still a sundown town, says Loewen. It reported just 89 African-Americans in the 2000 census, most of them probably residents of the state mental hospital. Elwood, Indiana, which has zero African-American residents, an annual Klan parade, and a vicious reputation, almost surely is.

The biggest revelation of Loewen’s book, however, is not the location or continued existence of sundown towns, but their number. When he started his research he thought he would find about 50 towns in the U.S. with a history of sundown practices. But after conducting on-site interviews, he was able to confirm the existence of 145 in Illinois alone. Based on census data and statistical analysis (all carefully detailed in the book) Loewen believes that by 1970, when such towns were most common, there were more than 470 in Illinois. This means that a majority of towns in Illinois may well have been sundown towns. Statistics like these eventually led Loewen to the broader conclusion that when a state, a suburb, or a neighborhood is all white, then it is probably all white on purpose.

At first, this may seem ludicrous. When Loewen asked white interview subjects about small, all-white towns nearby, they would often suggest that African-Americans didn’t live in them because nobody in their right mind would want to live in them. Moreover, the association of African-Americans with cities is so strong that black people take it for granted as well; when I saw Aaron McGruder speak a couple years ago he scoffed at the idea of a black person living in the WB’s Smallville.

Yet Loewen shows conclusively that the historic concentration of African-Americans in cities was a matter of discrimination, not choice. Before 1890 blacks were not particularly urbanized. Shortly thereafter, however, during a period historians refer to as the nadir of American race relations, racism in the United States became much more vicious. The Klan made a triumphant nationwide resurgence; segregation and disenfranchisement solidified in the south. In the north blacks and other minorities, like the Chinese, were forced out of rural areas and small towns. The result was a phenomenon Loewen calls the Great Retreat, in which African-Americans fled to the cities and wound up concentrated in ghettos. This process was well under way when the better-known Great Migration of the teens and 20s spurred the unprecedented resettlement of blacks from the south to the north.

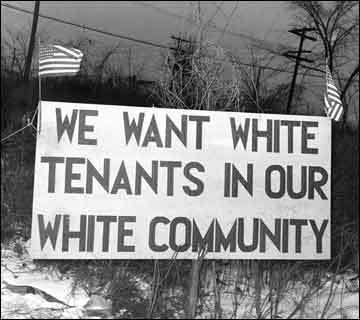

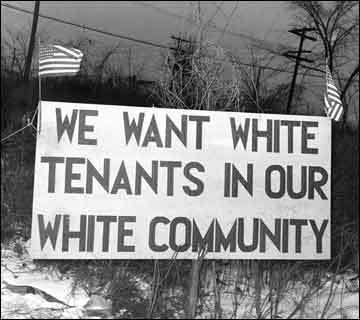

Sundown towns were generally restricted to the north and west, but sundown suburbs were a well-documented nationwide phenomenon. Redlining, steering, and restrictive covenants were standard in communities like the Levittowns of the 50s. Though they’re now less prevalent, not to mention illegal, such practices are still employed surreptitiously; Loewen reports incidents of steering in suburban Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, as recent as 2002. Violence against black home owners and their children has also been persistent, probably peaking during the 1980s.

The relative dearth of blacks in the suburbs–especially the wealthier ones–is often attributed to class. Statistically, blacks are poorer than whites. But Loewen argues that their exclusion from the suburbs is one of the causes of their relative poverty, not one of the effects. Until 1968 the Federal Housing Authority refused to underwrite homes built in communities that included African-Americans. Thus, African-Americans were excluded after World War II from what Loewen credits as “Americans’ surest route to wealth accumulation, federally subsidized home ownership.”

Black poverty isn’t usually blamed on the policies of white suburban home owners; instead, professors and pundits point to the excesses of the welfare system, or the failures of the welfare system, or the enduring impact of slavery on the black family, or what have you. All these explanations focus on how African-Americans live. Loewen’s book suggests, however, that if you want to understand racism in this society you must look at how, and especially where, African-Americans do not live. It isn’t what black people do but what whites do to exclude them that results in inequality. Whites won’t warehouse kids in crappy schools if the kids being warehoused are their own, they don’t want to fund massive police crackdowns if they themselves are likely to be caught in the dragnet, they don’t want to ignore fundamental flood preparedness if their homes are likely to be inundated.

Loewen does discuss some ways African-Americans can change discriminatory policies–by buying homes in mostly white communities, for example, or by supporting legislation to give federal fair-housing policies some teeth. Overall, though, Sundown Towns is not especially empowering: in Loewen’s narrative African-Americans tend to figure as victims rather than heroes.

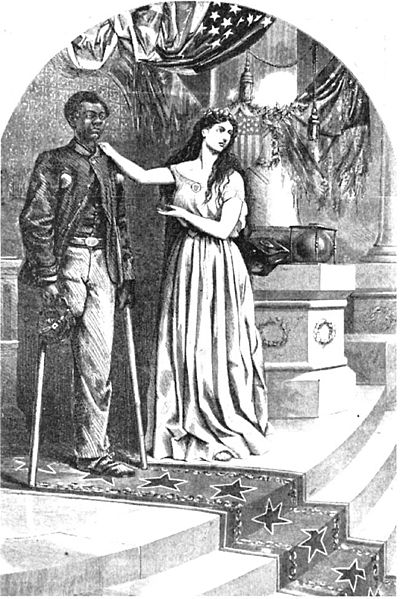

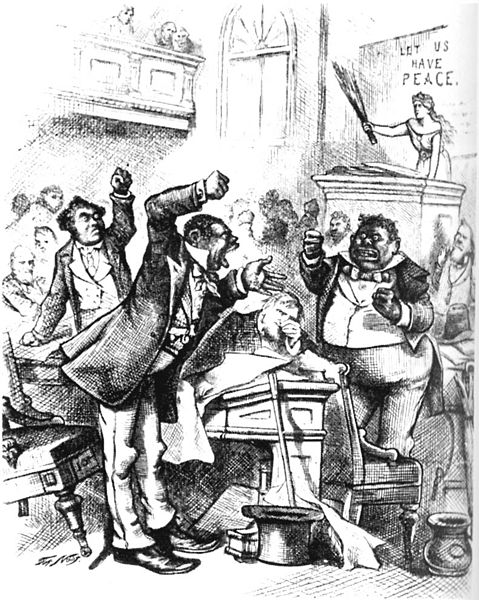

This is largely a function of his topic. In many ways the history of racism in the north is less hopeful than that of the south. Twice the south has been the site of utopian social experiments, during Reconstruction and the civil rights era. Neither movement was wholly successful, but during both periods African-Americans were able to make important social changes because of their connections to white society. After the Civil War, African-American links with white Republicans, both north and south, gave them a voice in southern government. The Montgomery Bus Boycott was effective because African-American dollars were important to white business owners.

In the north, however, connections between black and white communities were, as Loewen reports, deliberately severed. It’s no accident that Martin Luther King Jr. encountered a harsher reception in Chicago than in Atlanta. Nor is it an accident that black leaders in the north tended to be isolationist. James Baldwin’s famous question, “Do I really want to be integrated into a burning house?,” could only have been asked by a northerner.

Loewen points out that whites who live in sundown towns see no African-Americans and thus tend to believe they have no race problems. Similarly, the north itself, where whites and blacks have historically been more separate, has long been able to convince itself that racism is somebody else’s sin. But 50 years after the Brown decision, separate is still not equal. Illinois was the land of Lincoln, it was a supporter of the Union, and it’s now the home of the nation’s only African-American senator. But it’s also heir to a brutal and ongoing tradition of racism and segregation. All our problems wouldn’t be solved if every person in Chicago read this book, of course. But it wouldn’t be a bad place to start.