“The man who has no sense of history, is like a man who has no ears or eyes” -Hitler

I hate Berlin by Jason Lutes, but I feel bad.

I feel bad for singling out Lutes (as opposed to other more successful folks I hate like Brandon Graham or Frank Quitely), some poor dude who is just working hard doing something he loves. Something decidedly uncool. With little hope of any reward. I feel bad for the version of myself (the idealistic, formalist one) who grew up in the nineties, but I hate him too.

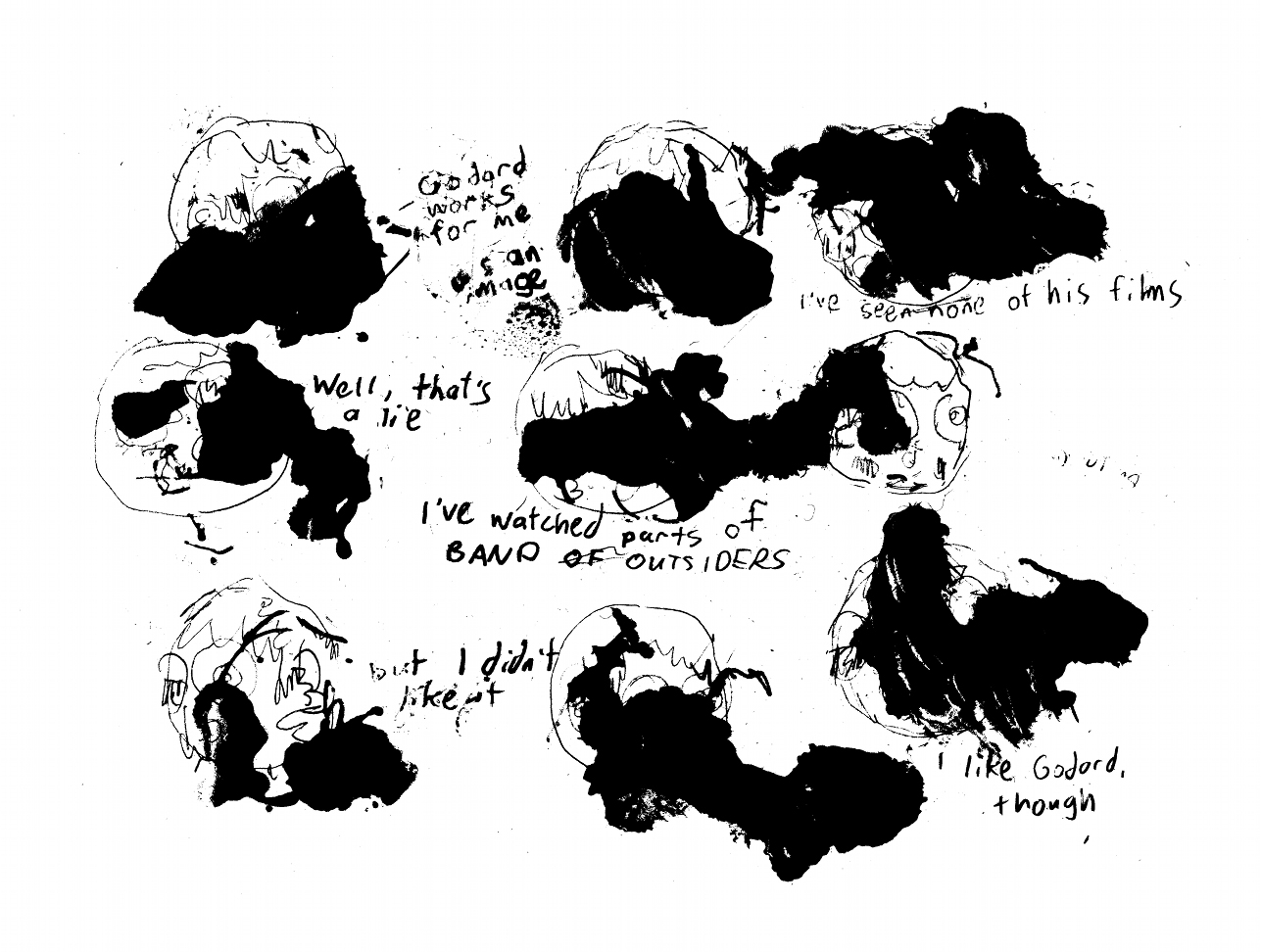

And let’s just get it out of the way that I haven’t read Berlin – only early chapters of it many years ago.

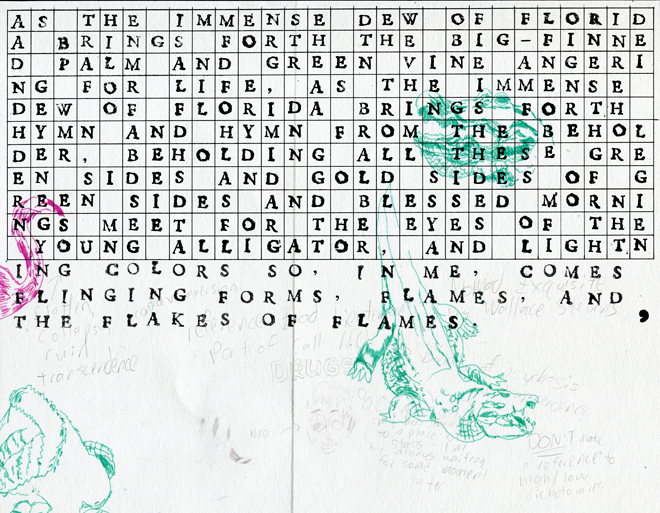

[pic of my copy – er, um, sold it – imagine a space on the shelf big enough for a “graphic novel”]

But I don’t think my lack of familiarity with the book makes much difference because I’m well enough acquainted with it (I’ve read/listened to interviews with Herr Lutes, in fact) to know that it’s what I find quintessentially boring, concerned with the past as parts, with correctness and historical accuracy, with piecing together a clockwork apparatus that utilizes the “comics medium” properly. parts is parts…

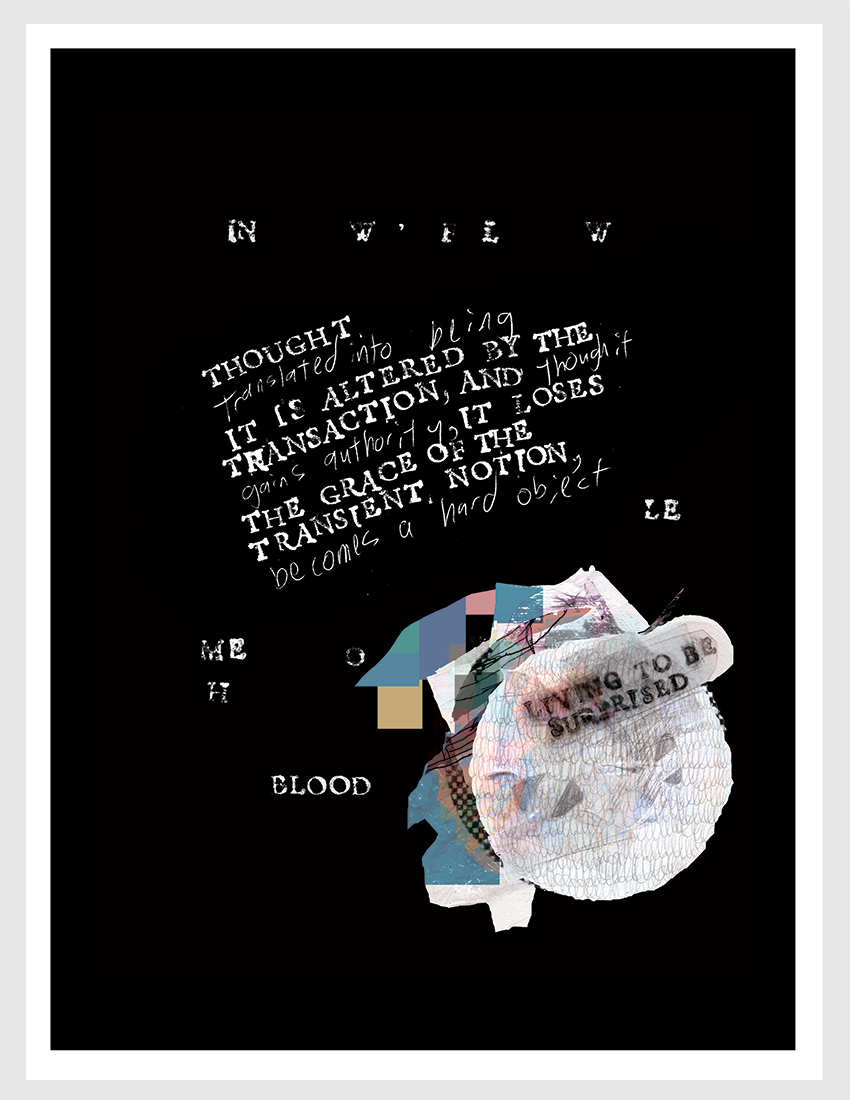

I have these two competing metaphorical agents operating inside my brain: the quick, spontaneous, associative agent and the slower, more organized analytical agent. The analytical agent seeks order, control – building systems that are self-contained and complete. The unresolved nature of the work produced by the quick, spontaneous part of my brain is more interesting, though, to me because its success or failure just seems to happen – I can’t unpack the way it functions.

So, yeah, here’s what I hate: when cartoonists give themselves over completely to their fascistic, organizational side, when the design of the system they’re building is the goal, when the components of the work are these discrete, mechanical operators that are masterfully controlled to achieve a particular end. I can appreciate the craft (and, really, the nineties college kid in me would love to be this sort of craftsman, where deeds would get him into heaven), but the work itself eschews excitement and delight in favor of propriety and cleverness.

It is creative process as control fetish, reducing life to pedantry and toil, cutting out the weirdness, the unexpected beauty that keeps me going.

Nuff said!

__________

Click here for the Anniversary Index of Hate.