“Who’s your favorite mutant, professor?”

If you’re going to teach a college course on superheroes, it’s a question you should be ready to answer. I wasn’t. My first thought was Lady Gaga. Artpop wasn’t out yet, so I must have been thinking about the human-motorbike cyborg of Born This Way. But instead I rattled off something about Magneto (his rare, bookworm incarnation adorns my blog). Now I’ve got a better answer. My favorite mutant was the first of them all:

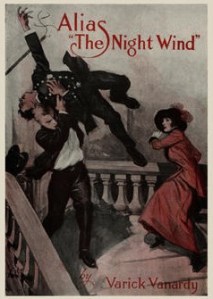

The Night Wind.

Never heard of him? You’re in good company. He stopped adventuring in 1919, three years before his out-of-work creator shot himself. He premiered forty years before Stan Lee first and most famously attached the biological term (already an evolutionary staple of post-Hiroshima scifi) to the world of superheroes.

In fact, “mutant” is so Marvel, I’m hesitant to use it outside their multiverse. I remember the narrative nausea my adolescent self felt when DC buckled under the popularity of X-Men and shoehorned their first “mutant” into Teen Titans. It was 1984, and Ex-Marvel writer-editor Marv Wolfman must have forgotten he’d switched employers (again). It didn’t help that the character was a joke, a mute mutant (is that a pun?). I had to google his name (Jericho) and his powers (mind control?), but remembered his dorky blonde curls all too well.

Not that Stan Lee’s first use of the term was impressive either. Two years cranking out his silver age pantheon (Fantastic Four, Hulk, Spider-Man, Thor, Iron Man, Dr. Strange), he hit his limit for origin stories. So the 1963 X-Men, “The Strangest Super-heroes of All!,” were all Born That Way like Lady Gaga.

As Professor Xavier professed in the first issue: “You, Miss Grey, like the other four students at this most exclusive school, are a MUTANT! You possess an EXTRA power . . . one which ordinary humans do NOT! That is why I call my students . . . X-MEN, for EX-tra power!”(Lee had one more origin story in him: Daredevil was hit by a radioactive truck the following year. Which pretty much proves the point about creative exhaustion.)

Alias “The Night Wind” crawled out of the primordial pulp goo of The Cavalier magazine way back in 1913, six months after Tarzan of the Apes set the new standard for superhuman adventuring. Like Superman, Bing Harvard, A.K.A. the Night Wind, had no problem tying “bow-knots in crowbars.” But instead of crashlanding from Krypton to be reared by mid-western farmers, or shipwrecked from aristocratic England to be reared by anthropoid apes, Bing was a foundling reared by an American banker.

He also possesses “a wonderful, God-given strength,” which was his “birthright,” what “his unknown father and mother had bestowed upon him as an inheritance.”

Peter Coogan terms him an “anomaly.” That’s a pretty good synonym for “mutant,” but the superhero scholar is talking genre tropes, few of which the character fits. I photocopied an excerpt for my class, and someone said it read like a supervillain origin story. Hard-working orphan framed for embezzlement turns his powers against the powers that be.

It’s true, Bing breaks the wrists of any cop who tries to arrest him, but after he clears his name (with the help of a lady cop who later marries him), he settles happily into law-abiding domesticity. The truly anomalous gene in the series is the never-solved mystery introduced in its opening chapters:

Who are Bing’s parents?

Jericho, it turns out, is the son of the villainous Deathstroke, his powers the product of biological experimentation done on his father. All those Marvel mutants can be traced back to Celestial tampering in the gene pool millions of years ago. But Bing? Frederick Van Rensselaer Dey (writing as his alter ego Varick Vanardy) didn’t care. Dey had cranked out Nick Carter dime novels for decades, but the Night Wind peters at four. The fact is frustrating, but even if I could sit down with Frederick over coffee in Dr. Doom’s time-travel machine, I’m not sure I would steer him any differently.

Bing’s real superheroism is only visible when you step out of the time machine and wander the nineteen-teens awhile. As a historical researcher, my first mistake is always the same. I assume past cultures are just like us, only in funny clothes. But immerse yourself in the period (I recommend the New York Times online database) and you realize you’re looking at a planet more alien than Krypton.

I always give my Superhero students a crash course in eugenics, a term, for those who’ve ever heard it, they associate with Nazi Germany not homegrown America. Where did the idea of killing the genetically unfit come from? Forget Auschwitz. The American Breeders Association of Cold Spring Harbor, Long Island recommended installing a gas chamber in every town in America.

This was 1911. Two years before the Night Wind started snapping police wrists. The Breeders’ other recommendations (immigration restrictions, racial segregation, interracial marriage ban, sterilization) became law as Dey was writing. Back then everyone simply knew the human race would devolve if Aryan supremacy wasn’t maintained. That was just common sense. That was the alien air everyone was breathing.

So if you were a recent immigrant, if your parents weren’t Anglo-Saxon, if you weren’t from good reliable Protestant stock, you were probably unfit. Genetic traits in those days included just about anything: poverty, promiscuity, feeblemindedness, criminality. Your parentage defined you. The cop who frames Bing says it all:

“Who are you, anyhow, I’d like to know? It ain’t nothin’ out uh the way that you should be a thief. I guess you inherited it all right. It’s more’n likely that his dad is doin’ time right now, in one uh the prisons, an’ his mother, too, maybe. It’s the way uh that sort. He don’t know who his antecedents was.”

Who was Bing? Who were his parents? Dey didn’t care. His hero was just born that way. And Dey blesses him for it. Literally. He declares his powers “God-given.” They’re not the result of eugenics movement’s so-called scientific breeding. He’s an accident, a genetic anomaly. He’s homo superior. Not the well-born superman eugenicists were obsessed with, but an up-from-the-muck mutant, defying the prejudices all of America was inhaling.

Dey was singing “Born This Way” a hundred years before Lady Gaga:

“I’m on the right track baby,

I was born to be brave.”