This first appeared on Splice Today.

Spanish cult schlock director Jess Franco’s made roughly a billion films, and I’ve seen like five of them, so I’m hardly an expert on his oeuvre. Still, the 1973 The Sinister Eyes of Dr. Orloff — recently released on DVD — seems like a fairly unusual Franco film. Mostly because it has a plot.

Of course, there are some typical Franco elements — murder, hot women in gratuitously short skirts, hot women falling out of their clothes, hot women murdering each other while falling out of their clothes, dream sequences, etc. etc. Not to mention the obligatory surreal detour into utter incompetence. The most delicious example of this here is a recurrent folk song sung in warbling tinny, out-of-sync lip-sync by the improbably ectomorphic and improbably named Davey Sweet Brown (Robert Woods.) Another highlight is disappearing subtitles, which (at least for non-Spanish speakers) add that dollop of incoherence that you’ve come to expect from any movie directed by Jess Franco.

So, like I said, one damn thing after the other, rather than, as in Vampyros Lesbos, one damn thing utterly divorced from the next damn thing, and then the third damn thing somewhere over there, and then, hey, breasts, and groovy music, and then lets go back to the first damn thing because why the hell not?

Which leads you to wonder, what caused Franco to suddenly turn himself into a bargain basement Hitchcock, with suspense and plot twists and dream sequences clearly marked off as dream sequences? Was he dropped on his head and suddenly set right? Or what?

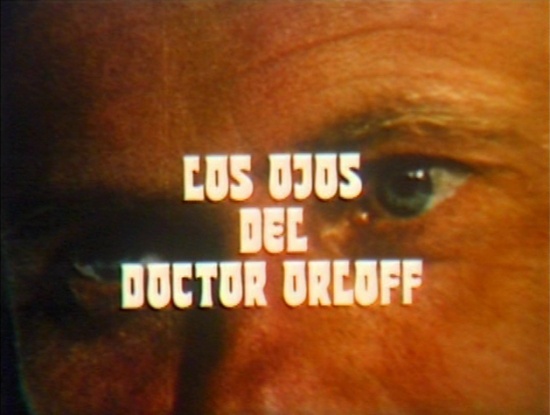

Probably it’s just the script or his collaborators or the phase of the moon or something banal like that. But I like to think, more poetically, that what happened was Dr. Orloff. The Orloff character appears in a number of Franco films, — though he’s played by a plethora of actors and from what I can tell there’s little actual connection between one baddy named Dr. Orloff and the next. In any case, this Dr. Orloff is all about the eyes; the film opens with a close-up of him staring intently, and when Melissa goes about her bloody business, we occasionally get flashes back to the same deadly ojos, looking commanding and fiendish.

Thus, Orloff functions essentially as a director within the film. His vision determines the action; he sees, and Melissa obediently staggers off, woodenly wreaking havoc in the way that Franco characters usually wreak wooden havoc — albeit, in this case, with somewhat more focus. Orloff’s directorial impulses are at times suggested even more explicitly. In one scene, he tells Melissa that her family thinks she’s crazy because, he says, he needs to “see her reaction”, as if he’s a filmmaker trying to calibrate his audience’s response. Shortly thereafter, he pats her on the should and tells her, “ In that little head of yours the dreams and the reality are mixed together.”

This is of course diagetically true of Melissa, who dreams about the real murders which on waking she forgets. But it’s also true extra-diagetically: film is both reality (there are real people up there) and dream, all mixed together. Melissa’s dream of murder is (unbeknownst to her) real, and that reality is (further unbeknownst to her) a fiction, or dream. When Melissa kills the loyal family butler on a foggy deserted road, the artificial mist and oversaturated lighting at times makes it hard to see what’s going on; the viewer is forced to become conscious of not seeing, and so of seeing. Similarly, Melissa’s slow stiffness, her awkward limping, and painful zombie overacting, reminds us of the naturalness of her unnaturalness. She looks like she’s in a film because she’s in a film, with Dr. Orloff (whose eyes appear in a quick jump cut) directing. The horrified butler looks up at her not to demand she stop but to ask her, “Miss Melissa, what are you doing?” — a question that actors in Franco’s films must have asked themselves and each other on more than one occasion. And after she’s done the deed, the camera zooms in for a fish-eye close-up on her before she clutches her head and falls to the ground. It’s a reminder that what’s in her is what’s watching her. The filmmaker moves around in someone else’s body until, eventually, he gets tired with the scene and discards his toy.

Imposing your own will on others is, of course, a sadistic pleasure; Orloff, with his giant needles, surely experiences it as such. Franco’s no stranger to sadism either; as just one example, his 1975 film Barbed Wire Dolls opens with the extended beating of a nude woman chained like a dog. Watching The Sinister Eyes of Dr. Orloff made me think, not only of the sadism in that scene, but of the sadism that must have been implicit off-camera for that scene to exist. What exactly was the conversation like in which Franco explained to the actress that she needed to strip down and put on a collar? And is that different in kind, or only in degree, from telling an actor or an actress what to say, where to stand, and how to feel?

Sinister Eyes also suggests, perhaps, that the rather desperate, over-the-top sadism in some of Franco’s movies might be linked to their fragmentation. Normally film directors are more like Orloff; they get their kicks not by elaborate beatings, but through more effective, and thus more subtle means of control. The Sinister Eyes of Dr. Orloff is Franco imagining himself as a filmmaker who has a hold on his film and the actors in it. When the evil doctor leans over Melissa at the film’s end and tells her with lip-licking sibilance that he is going to inject her with a drug that will make her “lose her mind completely and forever,” it seems less like a threat than like a promise to Franco fans. The doctor’s execution seals the bargain; the director is dead. Next film, we’re back to insanity.