(Editor’s Note: This was originally a paper for Chris Gavaler’s superhero class. We’re pleased to be able to reprint it here.)

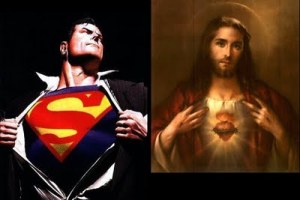

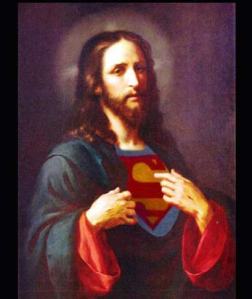

One may find it hard to look at the red underwear-clad Man of Steel as anything more than a super-powered illustration on the pages of Action Comics and the light of the big screen. However, when ignoring the tights and cape and analyzing Siegel and Shuster’s character closely, Superman can be seen as more than Jerry Siegel’s brainchild, but as the savior of the imagination of this young Jewish writer. Superman, or Clark Kent, first appeared in Action Comics No. 1 in June of 1938 right before World War II began in 1939, a time in which Jewish people needed a savior more than ever. In Superman Chronicles, vol. 1, a compilation of the earliest appearances of the Man of Steel, Siegel and Shuster introduce Superman, a modern messiah. Though the caped crusader’s stories are extremely dramatized and embellished when compared to his robed counterpart, the parallels of defending the oppressed, possessing unequalled power, and ultimately ushering in peace remain strong. Yet Siegel’s messiah surpasses his notion of the biblical messiah, Jesus Christ, through Superman’s conquering and avenging salvation of men. While both characters fulfill the messianic prophecies, Superman embodies the man of action that the oppressed Jews await. Here we see the pen of Joe Shuster and the mind of Jerry Siegel produce a fictional messiah comparable to Jesus of Nazareth in mission and grander than His spiritual salvation through physical action.

Jesus Christ and Superman both play the role of messiah, or leader and savior of a group of oppressed people. While salvation through Jesus is spiritual and salvation through Superman is physical, the mission of saving the oppressed remains constant. One of many messianic prophesies in The Holy Bible claims that the Jewish people “will cry to the Lord because of oppressors, and He will send them a Savior and a Champion, and He will deliver them” (New American Standard Bible, Isa. 19.20). Christians believe that this “champion” of the oppressed Jews came in the form of Jesus to deliver men from sin and to pave the way to heaven in His blood. In Action Comics No.1 when Clark Kent first dons his red and blue, Siegel introduces him as: “Superman! Champion of the oppressed. The physical marvel who had sworn to devote his existence to helping those in need!” (Siegel 4). Superman, like the prophesied messiah, is described as champion of the oppressed, but the deliverance he brings remains entirely physical and does not go beyond earthly oppression. In one of Superman’s earlier cases, he frees miners from the tyranny of a sadistic boss after which the newly enlightened boss, Blakely, asserts, “You can announce that henceforth my mine will be the safest in the country, and my workers the best treated…” to which Kent replies, “Congratulations on your new policy. May it be a permanent one! (If it isn’t, you can expect another visit from Superman!)” (Siegel 44). Superman caused Blakely to consider the abusive and dangerous conditions that he puts his workers through day in and day out, ultimately delivering them from their oppression. The Holy Bible proclaims: “God anointed Jesus of Nazareth with the Holy Spirit and with power. He went about doing good and healing all who were oppressed by the devil, for God was with Him” (English Standard Version, Acts 10.38). Though biblical Jesus did free the oppressed from the grasp of the devil and sin, the Jewish belief is that this deliverance is meant more tangibly in freedom from their worldly oppression, which Christ did not bring in their eyes. Though deliverances by Superman such as the salvation of Blakely’s mine workers in Action Comics No. 3 meet the Jewish stipulation obliging physical salvation, Christians believe that their spiritual deliverance is more than enough to call Him the champion of the oppressed. Whether physically super or spiritually godly, both men succeed in fulfilling this prophecy in their own way.

Though not quite as defining as the act of salvation, one of the most universal, unquestioned aspects of a messiah figure is the possession of unrivaled power and dominion. Powerful is an understatement when talking about “Superman, a man possessing the strength of a dozen Samsons!” (Siegel 84). He is a warrior and a powerful leader, capable of overthrowing corrupt rulers and strong-arming the evil. To the defenseless Jewish people in Europe, and even to these Jewish artists in the United States, these qualities made Superman the perfect messiah. Therefore, it is no coincidence that Siegel references Sampson’s strength, represented biblically when “a young lion came toward him roaring. Then the Spirit of the Lord rushed upon him, and although he had nothing in his hand, he tore the lion in pieces as one tears a young goat” (Judg. 14.5-6). Having already granted enormous physical power upon one of His servants, the Jewish people expected God to send a messiah with even greater physical power to lead them in battle against their oppressors. Again, Jesus’s power comes in a less tangible medium than His bulletproof analog. Superman, however, was granted this physical prowess by his Jewish “fathers,” continuing to directly allude to the story of Samson when “with incredibly agile movement, he twists aside, seizes Leo by the scruff of his neck… ‘Wanna play, huh?’… And carries the ferocious carnivore back to its cage as though it were a harmless kitten!” (Siegel 95). Instead of physical power to fight a lion, the gospel characterizes Jesus with the power and strength of character of God. He is called “Immanuel (which means, God with us)” (Matt. 1.23). As God on earth, Jesus is given “all authority in heaven and on earth” (Matt. 28.18). The bible seems to define power as spiritual authority rather than the physical strength of Superman Chronicles. Given that Jesus did not decide to use His authority to physically free the Jewish people from their Roman oppressors, instead choosing to defend men in spiritual warfare, it is not hard to see why some Jewish people of the time and in biblical times would prefer the tangible power shown by Superman. These passages do not only allude to Superman’s association with Old Testament prophecies, but they suggest that Siegel and Shuster considered these prophecies and stories during Superman’s conception, consciously creating a messiah figure.

Finally, the biblical Jesus and comic book Superman differ greatest in the nature of the peace reached through their actions. While both saviors usher in peace, the dichotomy of the spiritual repercussions of Jesus’s actions and the physical actions of Superman continues to appear. The Old Testament verse promises that the messiah “shall judge between the nations, and shall decide disputes for many peoples…nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war anymore” (Isa 2.4). In biblical times, people believed that this promised peace between the Romans and the Jews, among other nations, and this would give them their salvation and deliverance. Though Superman uses a vast amount of violence, he is constantly fighting for peace. In one of the Man of Steel’s most broad—and possibly his most destructive—rescues, he attempts to save the slums when he discovers that “‘the government rebuilds destroyed areas with modern cheap-rental apartments, eh?’ Building after building crashes before his attack! ‘Then here’s a job for it! – When I finish, this town will be rid of its filthy, crime-festering slums!” (Siegel 109). This passage acts as the perfect image of the messiah figure riding into battle to create peace among his people through completely active, violent, and destructive means. While Superman, or rather his writer Jerry Siegel, seems to prefer this method of justice, comic book readers can discover examples of peace through diplomacy. In Action Comics No. 2, he even settles a war between nations by bringing the opposing war-lords together and explaining: “‘Gentlemen, it’s obvious you’ve been fighting only to promote the sale of munitions! – Why not shake hands and make up?’ And so, due to the conciliatory efforts of Superman, the war is halted” (Siegel 30). Shuster draws Superman as a logical, supportive mentor, helping men to choose peace themselves rather than forcing it upon them. In the same way Jesus, King of the Jews, sought to bring His people to spiritual and eternal peace through His defeat of death in the form of resurrection. He points back to the prophecy in Isaiah by reassuring His disciples that “I [Jesus] have said these things to you, that in me you may have peace. In the world you will have tribulation. But take heart; I have overcome the world” (John 16.33). This promise does not assure that God’s people will live life on Earth in utter peace and harmony, at least by the society’s definition, but rather looks to the peace granted by admission to the eternal paradise of heaven. However, Jesus does additionally promise peace on Earth in the form of the Holy Spirit, referred to the Spirit directly as “Peace” in reciting: “Peace I leave with you; my peace I give to you. Not as the world gives do I give you” (John 14.27). Though this peace is more physical than that spoken of in the passage above, it remains a spiritual peace in that it perpetuates as an inner peace despite the trials and tribulations of life. The peace brought by Superman does not deal with the spiritual or how people deal with situations, but focuses entirely on eliminating as many tribulations as possible; therefore, Superman’s goal of peace is yet to be realized. Regardless of the completion of his goal, the physical and spiritual missions perpetuated by Superman and God-as-man yield sufficient peace to bestow both heroes with the title of a messianic peace-bringer.

While Siegel found inspiration for the last son of Krypton in the only begotten Son of God, the two differ in one very distinct way: Jesus is the spiritual savior of eternal life while Superman is the physical savior of life on earth. In their defense of the weak, their strength in battle, and their strides towards peace, it is fitting to call Superman the Messiah of the twentieth century, at least in the fictional comic book world. With Nazi Germany attempting to enslave and oppress the Jewish people, the physical salvation of Superman would understandably sound more appealing to some than a spiritual salvation, just as it may have to the Jews of biblical times under the heel of the Roman empire. Just as the Christian messiah reshaped the religion of those Jews who accepted His teachings, “Superman is destined to reshape the destiny of a world!” (Siegel 16)… at least in the comic books and in the minds of his avid readers.

Works Cited

The Holy Bible, English Standard Version. Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2010. Print.

Holy Bible: Updated New American Standard Bible. Anaheim, CA: Foundation Publications, 2007. Print.

Siegel, Jerry and Joe Shuster. Superman Chronicles. V1. New York, NY: DC, 2006, Print.

(Tyler Wenger is an upcoming sophomore at Washington and Lee University from Franklin, TN. He is a pre-med student planning on majoring in Neuroscience and he has been both a Christian and a die-hard Superman fan for his entire life.)