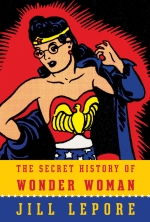

Earlier this week Jeet Heer and I had a long conversation about Jill Lepore’s Wonder Woman and it’s strengths and weaknesses. Comics scholar Peter Sattler weighed in with a long comment, which I thought I’d highlight here.

Earlier this week Jeet Heer and I had a long conversation about Jill Lepore’s Wonder Woman and it’s strengths and weaknesses. Comics scholar Peter Sattler weighed in with a long comment, which I thought I’d highlight here.

Just finished the book, Noah, and I hope you won’t mind if I use this as a place to write a few thoughts, which I think intersect with your conversation.

1. Lepore’s lack of engagement with more current Wonder Woman scholarship, at least in her notes, is striking, especially considering her attention to far more recent writings on such figures as Wertham (e.g., Beaty, Tilley). Nonetheless, I think that Jeet’s genre-based point speaks a bit to this: Lepore is not invested in the “secrets” of today, as much as the secrets of yesterday — the past that ends mainly with her narrative, in the 1970s.

2. That said, I take Noah’s point about how the issues of queer identities — and even the practices of queer life in mid-century America — is barely a topic for this book. Lepore actually spends little time talking about sex, sexuality, or theories of same (Marston’s or otherwise). Dramatically more space is given over to issue of suffrage, to the economics and power dynamics of women’s work, to the lie detector and its place in the juridical-military system, and to the shitty way that women are treated by men. The material on sexuality is there, but hardly dwelt on or analyzed. Indeed, with its New Age and Aquarian designations, Marston’s ideas about love and submission as much an object of fun as anything else.

3. But to be clear, the lack of a “queer” history or theoretical context is certainly intentional and not an oversight. The “secret history” of Wonder Woman, for Lepore, is not a secret of sex or love or the closet; it is a secret history of politics. It is a story of the deep roots of feminism: it’s about the fight for women’s rights. (Even the discussion of chains, for example, focuses far more explicitly on its ties to feminist imagery than to kink.) And the book’s commitment is to tracing those roots as thoroughly as possible. An alternate title might have been “the political origins of Wonder Woman.”

4. Pace Noah, I don’t think Lepore does much to privilege her own or her reader’s sleuthing skills. Unlike her New Yorker article, Lepore never puts herself into this story, trying desperately to break through the walls of silence. The “secret” framing — just like the academic framing — is actually pretty thin. It’s the intersection of documents and stories in the middle that counts.

5. When it comes to the “waves of feminism,” Lepore both wants and does not want to make the argument that seems to be promised. She definitely has a passage on the forgetfulness of the radical wing of the second wave, with Shulamith Firestone visiting Alice Paul and not being able to identify portraits of the nation’s most famous feminists (and the Red Stocking’s hatred of Wonder Woman). And she then paints post-Roe feminism as a process of in-fighting, with people trying to out-radicalize each other.

At the same time, I think her heart wasn’t really in this: the real story is over, and she seems to be looking for a quick rhetorical punch. As a historian, she’s just not that invested in her New Yorker claim that Wonder Woman is “the missing link” (ha!) chaining the suffrage movement to “the troubled place of feminism a century later.”

6. A telling moment: Lepore tell us that historians have tended to use the “wave” metaphor to imply that nothing much happened in feminism between the 20s and the late 60s. Here is the totality of that argument: “In between, the thinking goes, the waters were still.” The note to this passage, oddly, only refers to writers who have challenged the “wave” metaphor — which Lepore then does herself later, saying we should call it a river. Oddly enough, it is Lepore who then makes the claim that nothing much has happened in feminism between 1973 and today, characterizing the years as a series of generation of women, all eating their own mothers.

7. The book is the most exciting and well-researched piece of scholarship related to comics I have ever read. At the same time, I hesitate to call it “comics scholarship,” per se. And this isn’t simply a matter of guarding the field’s borders, keeping it safe from poachers. THE SECRET HISTORY OF WONDER WOMAN, in the end, just doesn’t seem particularly interested in Wonder Woman comics, Wonder Woman stories, or Wonder Woman art — except as “telling” and glittering superficialities of a much more interesting biographical and historical tale.

She does not spend much time looking at Wonder Woman as an artistic creation, giving shape to particular concepts or exploring certain obsessions. Rather, the links of the comics to history emerge in the book as series of equations, or even one-way vectors: Hugo Münsterberg => Dr Psycho; Appellate Judge Walter McCoy => the stammering Judge Friendly from the comic strip; Progressive Era fights and imagery => Wonder Woman’s fights and imagery; Marston later behavioral troubles with his children => Wonder Woman’s later stories with kids named Don and Olive.

Moreover, these claims are not so much supported as *revealed* — and very briefly revealed, in most cases — like when Lepore parenthetically discloses that Marston had written a story about Wonder Woman and rabbits after talking for a page or so about the pets at Cherry Orchard. Large passages of the book take this form: tell an exciting and detailed story about Marston or Sanger, then close the chapter or section by saying, in essence, “this happen in Wonder Woman too.”

8. This isn’t to say that the book doesn’t change the way we look at Wonder Woman. The comic, after one is done with Lepore, seems to just vibrate with historical energy: the last, unexpected explosion of Progressive Era feminism. But it is not really a book about Wonder Woman; it is a book about Marston and the world of women in which — and out of which — he made his fame.

Marston comes across, in the end, as a classic American charlatan and genius — and a genius due in no small part to his charlatanism. He is a huckster, a relentless self-promoter, an almost unending failure, and even (in my opinion) a misogynist. His heart, politically, is in the right place, but his ego and his loins are often someplace else.

9. Perhaps this makes the biggest secret of Wonder Woman the fact that she ended up existing in a such a potent and coherent form at all, coming as she did from the mind of a man who (after reading Lepore’s account) seems to have been a mass of contradictions, opportunism, and outright absurdity.

Luckily, the book seems to say, the women in his life and his world were strong enough, politically and philosophically, to counteract Marston’s personal weaknesses.

The book’s biggest secret: Women and feminism — not Marston — created Wonder Woman.