For years I have recommended Skim, by Mariko and Jillian Tamaki, as one of my favorite comics. While beautifully illustrated and competently told, I’ve been hard-pressed to explain why I love this book so deeply. I often fall back on biographical justifications— I was once a teenager who romantically pursued someone significantly older, and its rare for me to find a book that accurately captures this experience. I’m tired of this explanation, as it does a disservice to Skim, which is an exceptional work on its own terms. I’m going to try to articulate, here and now, why Skim is a comic I keep coming back to, and shows much more promise for the medium than I see it accorded.

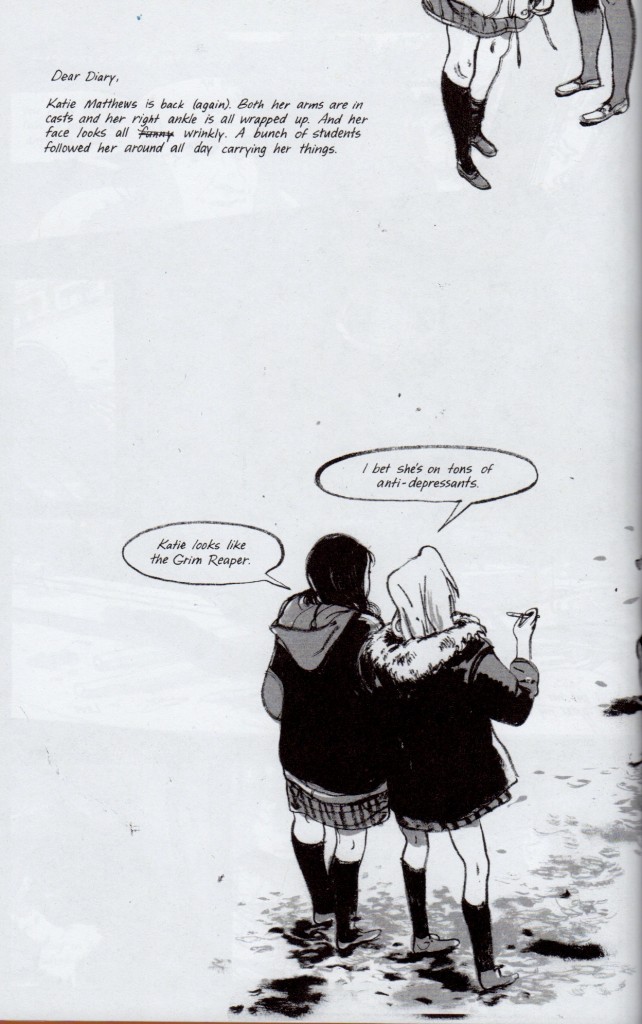

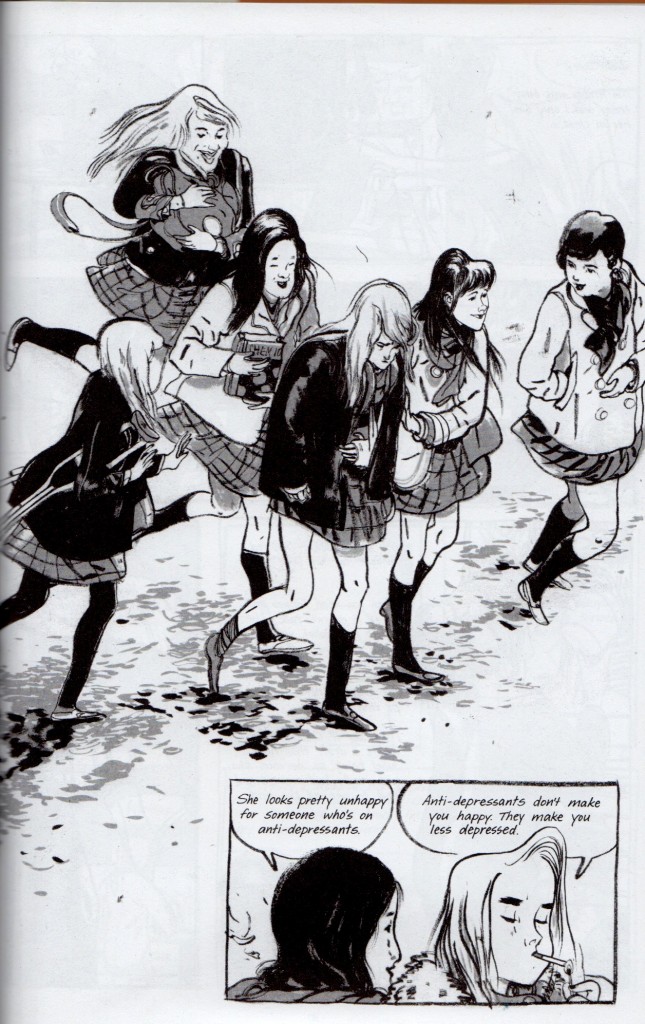

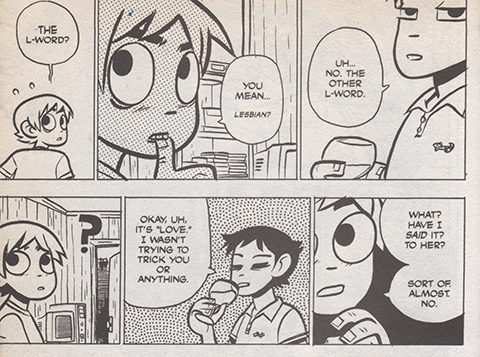

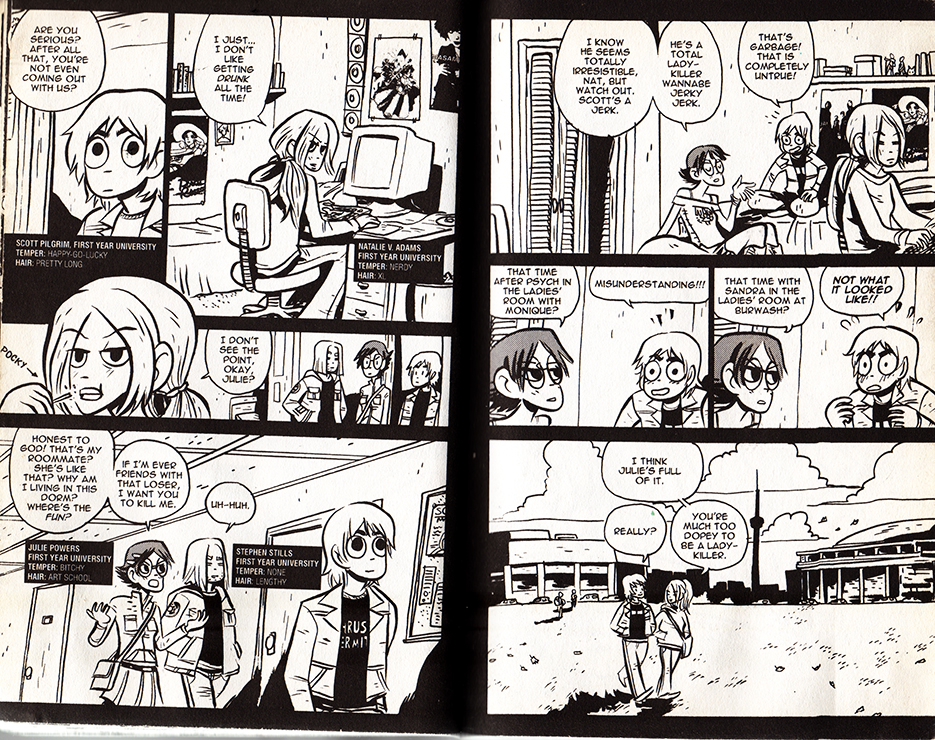

Skim is told from the perspective of a high school junior, Kimberly Keiko Cameron, nicknamed Skim because she is not. Skim chronicles of the fall semester of several young women, who navigate an all-girls Catholic school fixated on the suicide of a local boy. As counselors and students perpetuate an indulgent cycle of hysteria and healing, Kim and Lisa, two best friends, lampoon the faculty and student-body. As they grow apart, Kim falls in love with the young, maverick teacher Ms. Archer. Ms. Archer crosses the line, realizes her mistake, and immediately begins to withdraw from Kim and the school. Meanwhile, Katie, the well-loved ex-girlfriend of the local boy, becomes caught in the hurricane-eye of the school’s morbidity, and eventually enters onto Kim’s horizon.

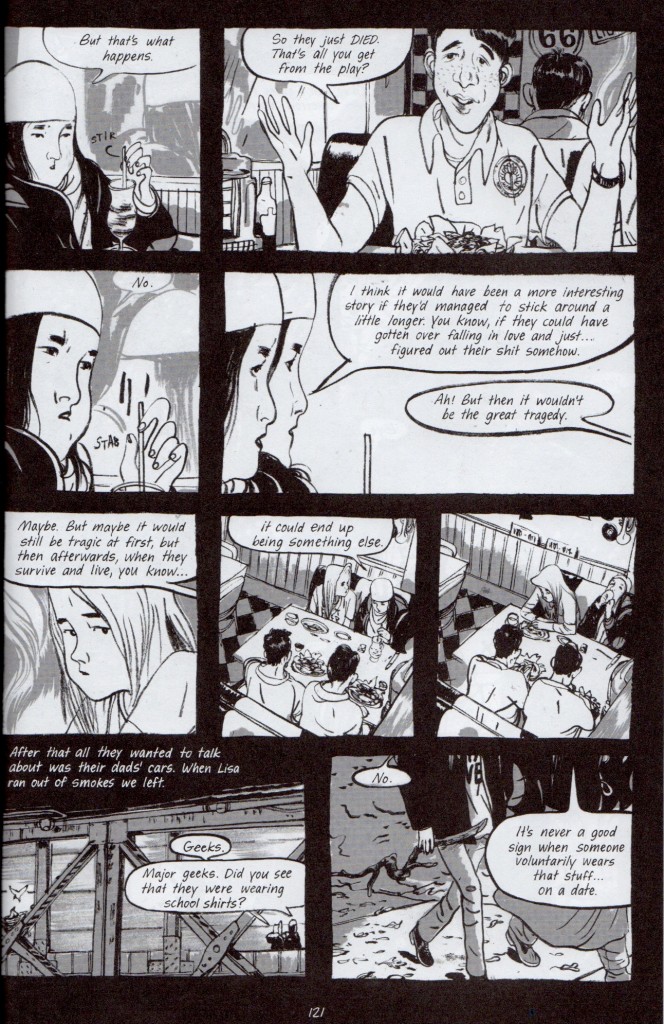

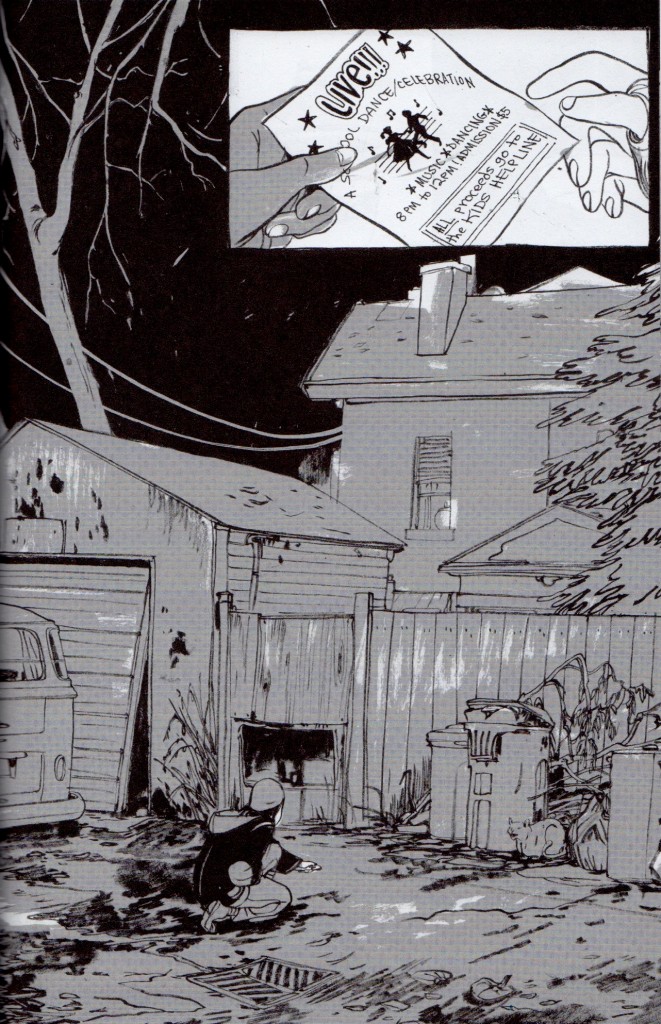

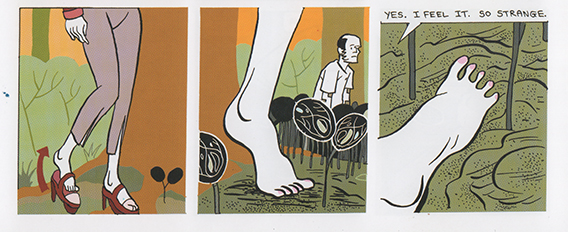

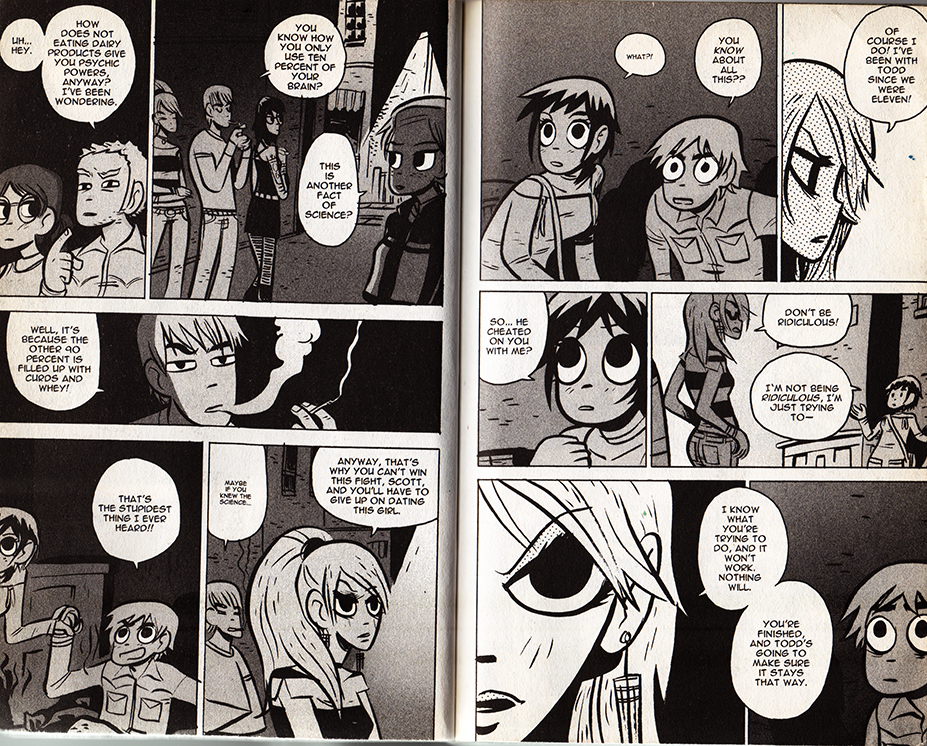

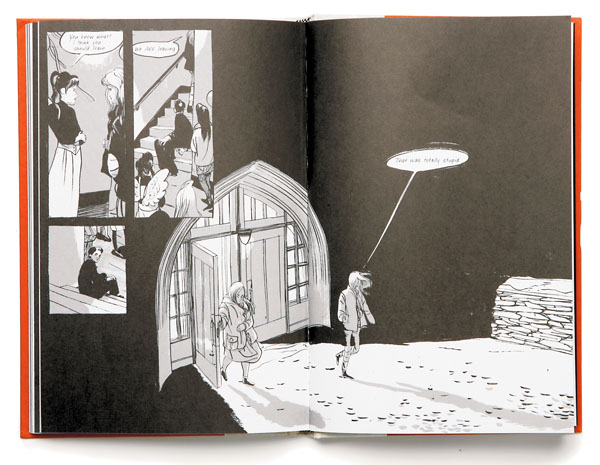

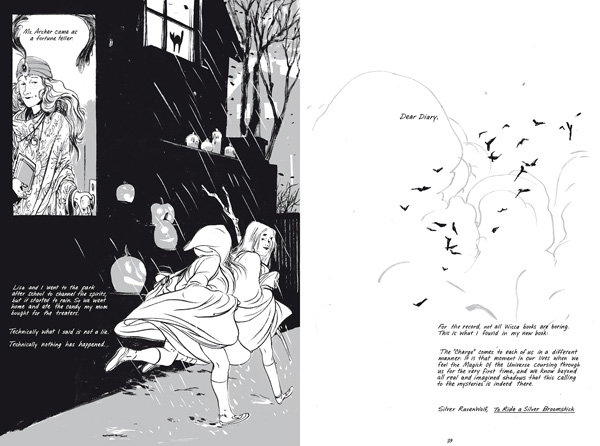

Skim is darkly comic, though it hits the usual targets—small towns, personal religion, high school, high school girls. Kim and Lisa visit a Wiccan circle that turns out to be an Alcoholics Anonymous recovery group. Kim receives a kitschy mug from her father’s girlfriend, adorned with a ludicrously ignorant slogan. A group of self-absorbed ‘popular’ girls form a club called ‘Girls Celebrate Life!.’ Etc. etc. Smartly, Kim and Lisa are not cast as the sole bastions of truth. Lisa spouts punk cliché after punk cliché, and while Kim knows better, she can only respond with clichés in turn. There’s comedy to be mined in the pathetic graspings of a group of hypocrites and posers, sure. Remarkably, Skim’s cynicism plays second fiddle to a sense of grace. Dark humor drops like stones through the surface of the narrative—the story is actually formed by the rippled answer to these plunks, a visual whisper that the world is much bigger, stranger and more beautiful and than these ironies suggest. Lingering hands, a telephone pole, or footprints in the snow somehow always get the final say.

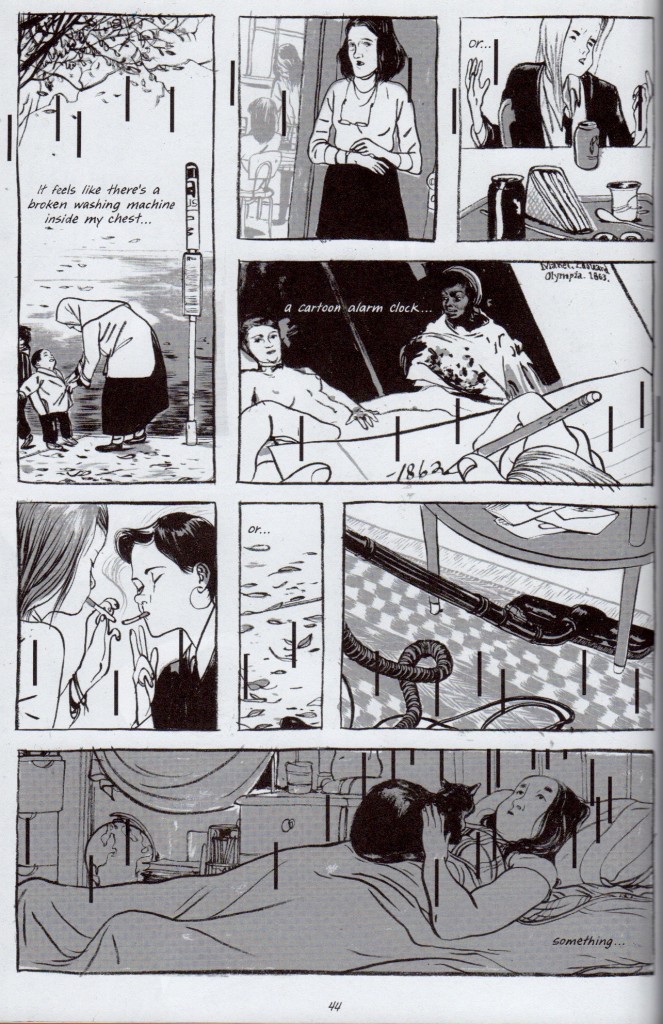

Skim’s attention to its story-world both accentuates and minimizes the scope of Kim’s depression– if there is a world outside black comedy, this world also continues after tragedy. Kim is observant enough to know that she’ll recover from her loss, but she’s lonely. She simply wishes this recovery was more important than the tragedy everyone seems hungry to witness, as she vocalizes below:

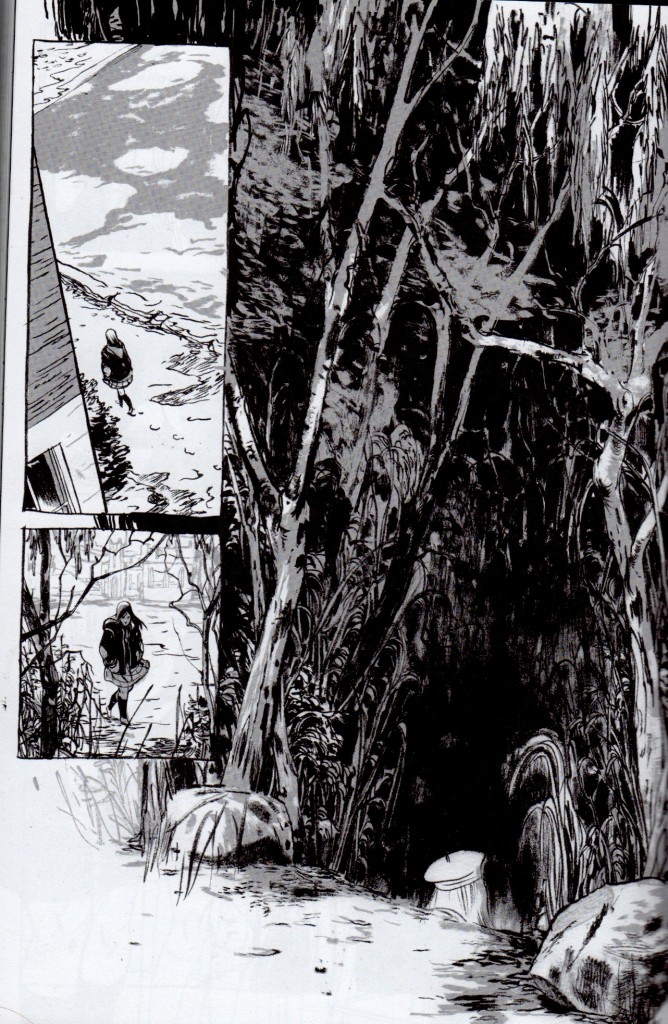

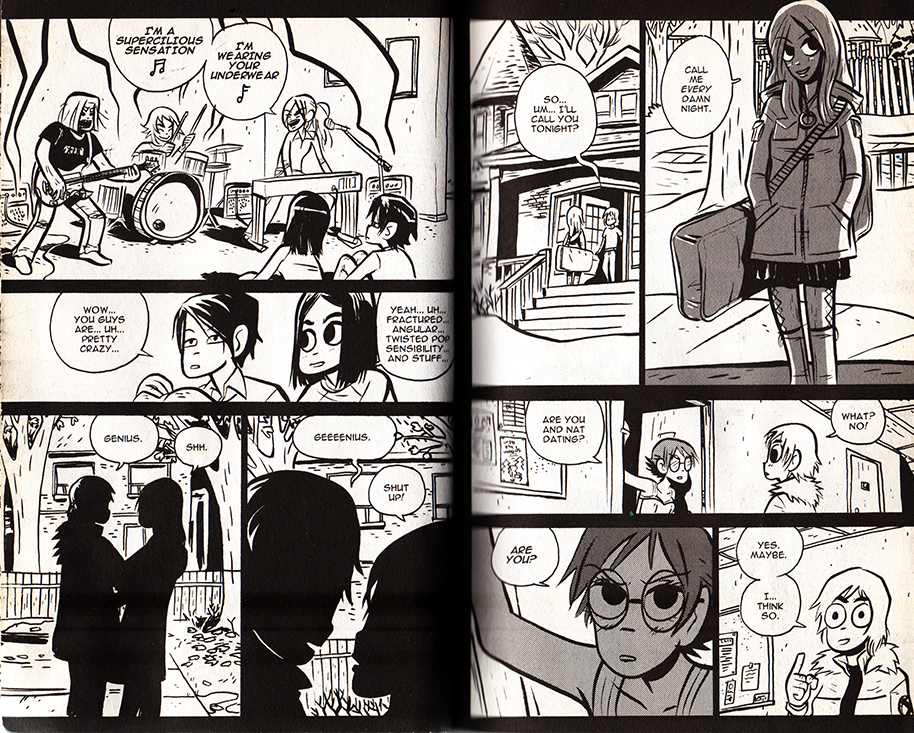

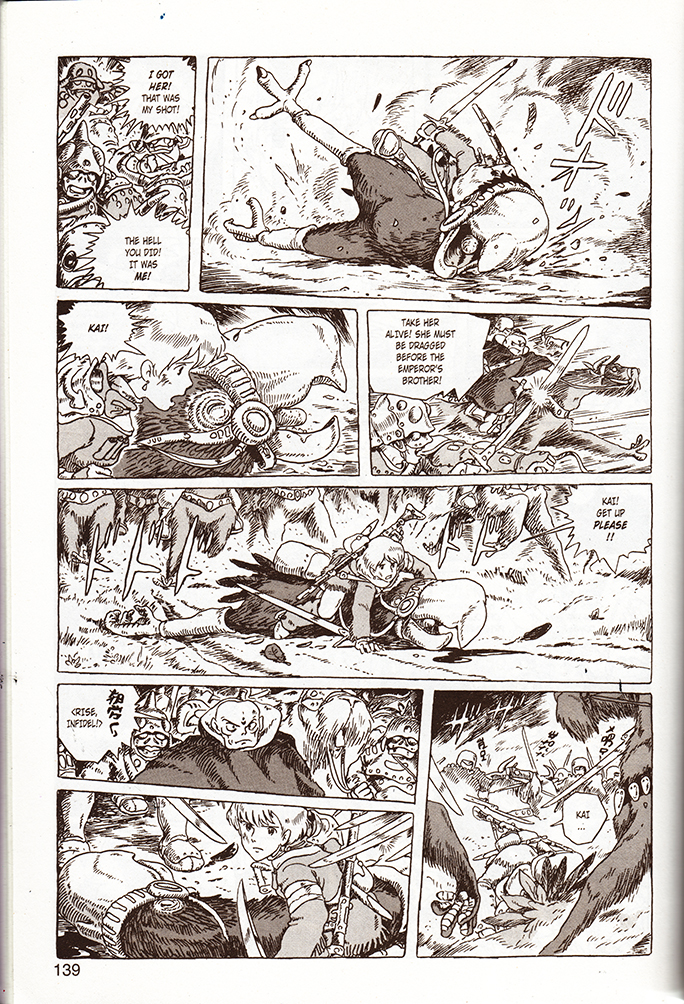

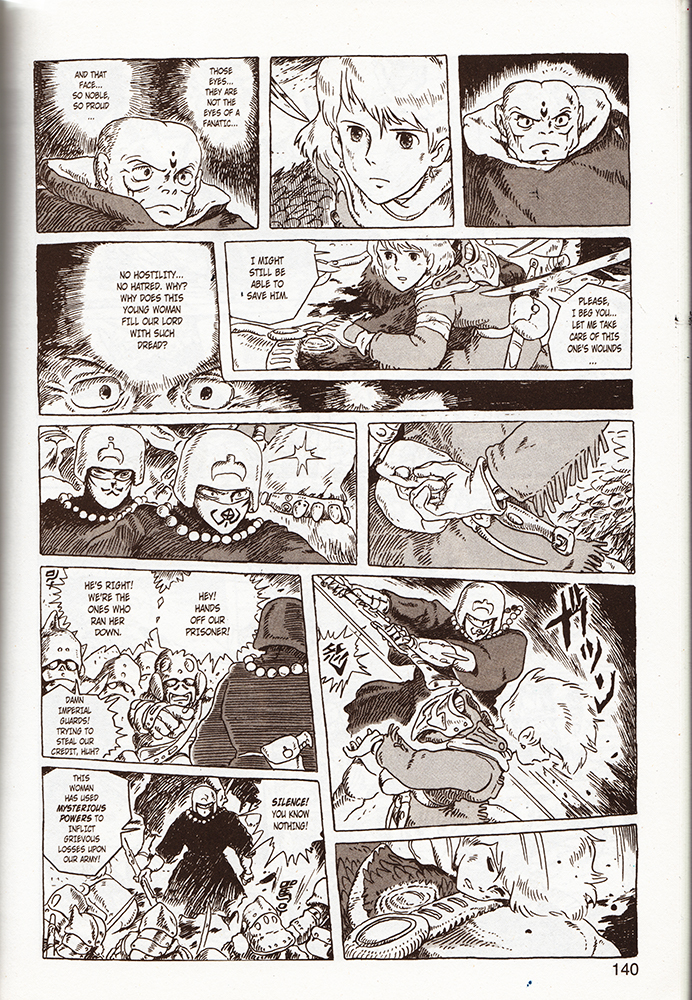

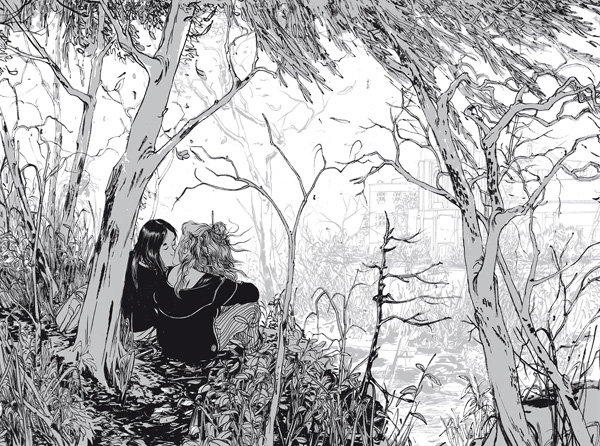

Kim’s yearning for that “something else,” describes Skim’s particular kind of storytelling. The book passes by the iconic moments of adolescence in favor of their lingering aftertaste– the doubt following confident pratter, the assurance found in being abandoned. Its humor can be a bit manufactured, but its nocturnes are feral and strange. Skim‘s characters find their true colors at night. When Ms. Archer quits teaching, Kim follows her at her house after school, where she is reluctantly welcomed inside each time. She quietly absorbs a family photograph, the clutter, the way Ms. Archer lifts her cat with one hand. A heady mood leaks from every dirty teacup and grey corner, leaden with hard decisions. Skim includes its environment and telling gestures, occasionally at the expense of the conversation they lead to. Most importantly, we hear Kim’s voice immediately after each incident reeling from or reconciling what happened. I appreciate that Skim judges this moment spent walking home as worthwhile, or even more valuable, than the confrontation itself. This is where Kim slips into uncharted territory. Similarly, Katie and Kim see each other fully one late night, escaping prom. Kim suffers insomnia, which leaves her both exhausted and exalted.

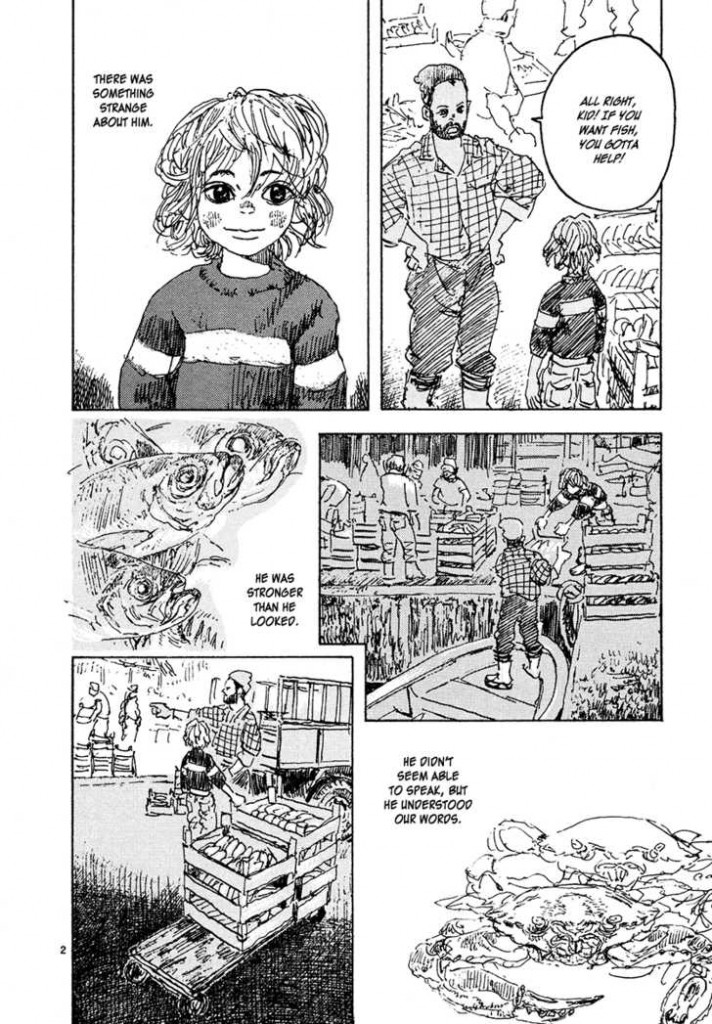

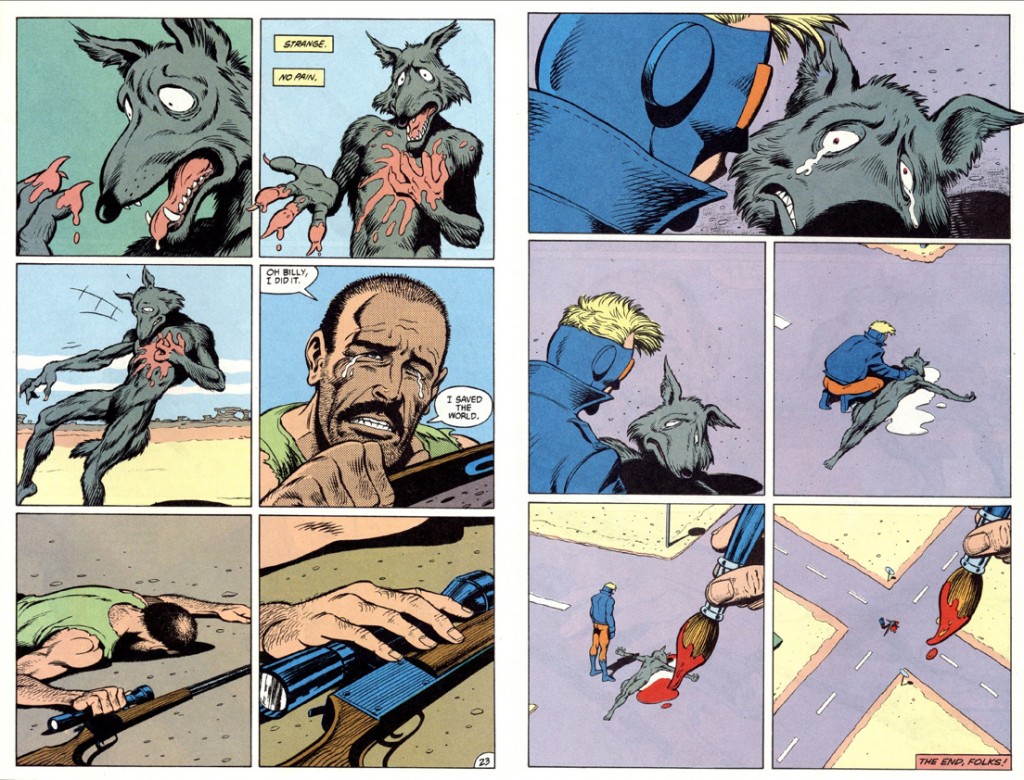

Skim could have easily been a much narrower story without its sinewy brush-work, and the nuance of its characters’ performances. It’s laudable that Mariko Tamaki, the writer, doesn’t overreach her character’s limited voices. Kim’s speech above is about as articulate as anyone gets. It’s an awkward but honest testament for the story. I also appreciate Jillian Tamaki’s figure drawing, which is at times grossly loose, pinched and contorted– tiny misshapen hands and swollen legs abound. They capture the sensual topsy-turvy of confused vision. Skim is a pretty book, but not a stunning one, for the best. If the book had been heart-stoppingly beautiful, the panels might have crystallized the moments, rather than letting them flow into a magpie’s nest of dirty lines, black pools, and wintry negative space.

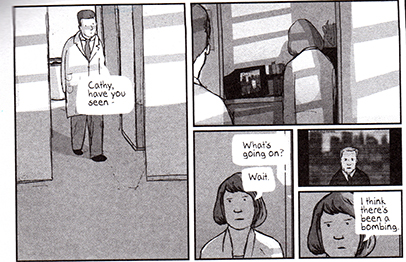

Skim’s perspective is similarly messy, and inconsistently shifts between diary entries and third-person. The clumsy steps back and forth nevertheless give breathing space. Jillian and Mariko cover several complex transformations over three months. High school dramas often take the symbolic course of autumn to spring. What kind of personal-growth narrative starts in fall and ends in winter? Perhaps its a mistake to classify Skim as a ‘personal-growth’ narrative at all. While the characters seem to be better people by the end, no one acts any differently. Lisa is carried away in love. Ms. Archer flies off for somewhere new. On the final page, Kim goes off to meet Katie. She approaches a woodland very similar to the one which she and Ms. Archer frequented. Only the top of Katie’s head is visible, dressed in its little cap. She’s more a ghost, or a pale echo of Ms. Archer’s body pages before, than a person. Its ambiguous as to whether Kim’s budding friendship with Katie has begun to slide into something else. It’s possible they are all about to repeat the same intimate miscalculations.

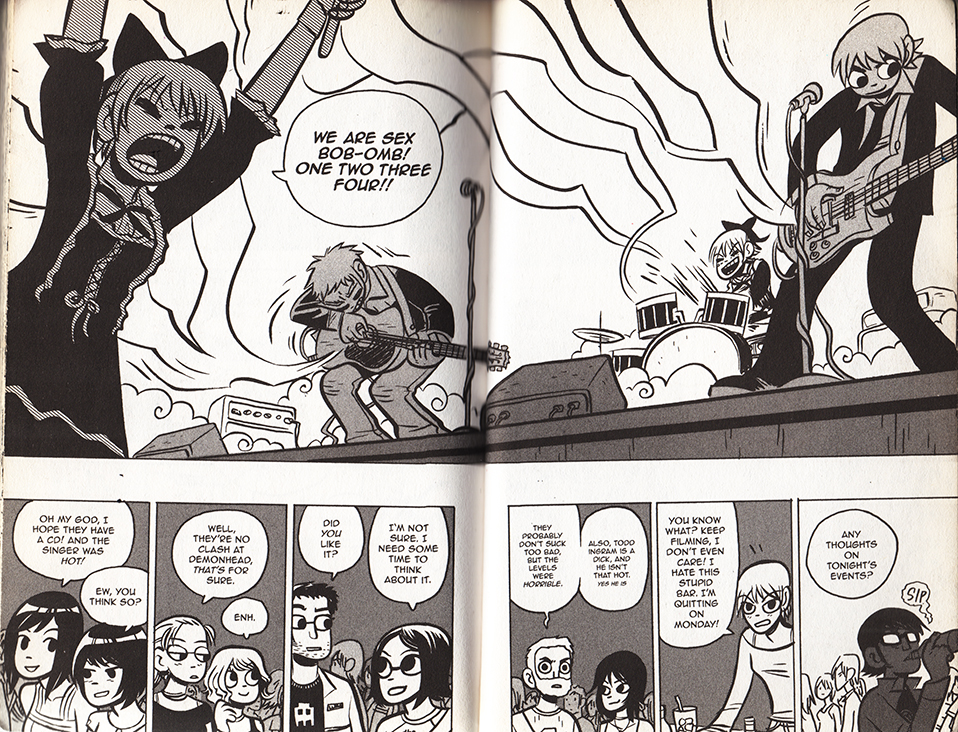

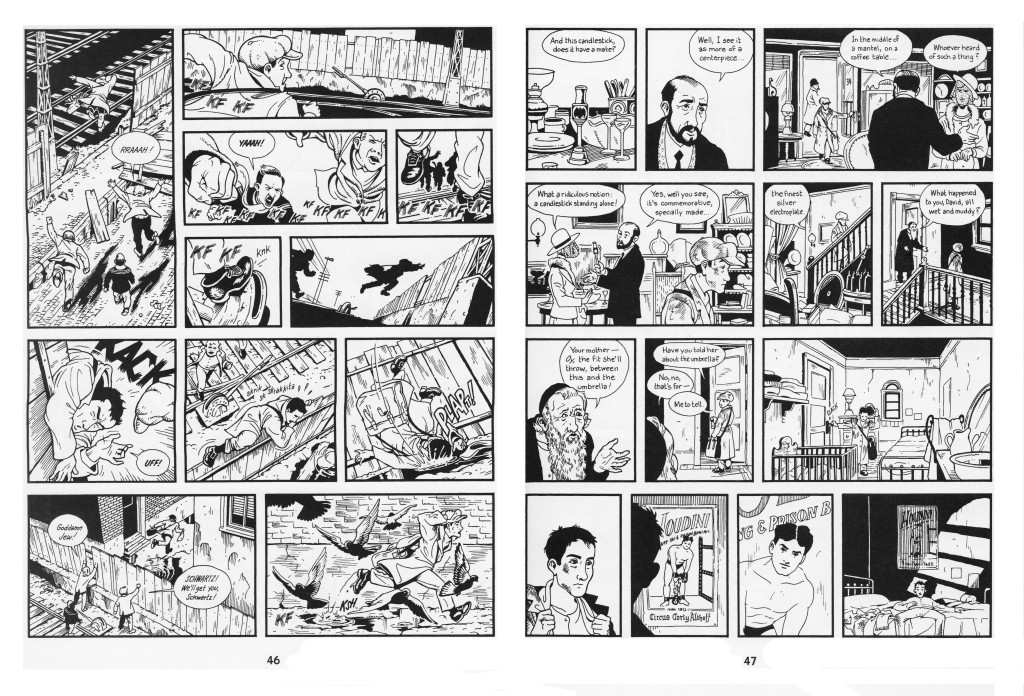

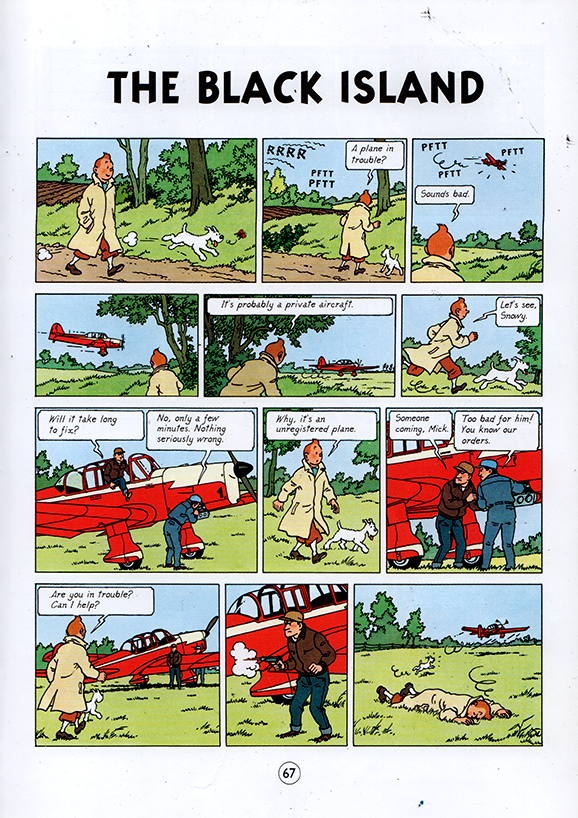

I admire Skim for its brave vulnerability, its tone and message, and also for its independence as a comic work. It doesn’t traffic in wish-fulfillment, overt camp, nor nostalgia– surprising for a comic book about high school. It is self-deprecating without secretly being self-congratulatory, a la Art Spiegelman. It isn’t distracted by its ‘comic-ness.’ It is not epic, nor controversial. It is not drawn in an iconic way. It is also completely about young women, and quite short. Frankly, there isn’t much cultural currency to be gained by reading Skim, discussing it, or recommending it. American girlhood is undervalued and easily reduced. Skim is a relatively unambitious book, but this isn’t a bad thing. Unpackaged from the neurotic cultural agendas that reinforce comic’s masculine, canon-mongering, Skim treats comics as a legitimate medium fit for a self-contained story. It doesn’t talk about being a comic, or push the boundaries of the medium for their own sake. It doesn’t need to prove that ‘comics aren’t for kids anymore.’ It simply tells an adult story. This resistance to being impressive or fantastical, combined with its ‘young adult’ high school setting, deplorably positions it outside the conversation of contemporary comics.

Skim’s comic treatment does justice to, and perhaps deepens, an excellent story. At the end of the day, I believe comics would be more widely attended to if they did just this.