This first ran on Comixology.

_____________________

Female super-heroes can be many things: Amazon warrior, out-of-control telepath, deadly ninja assassin. But whether in swimsuit, bodysuit, fishnets or boob window, they’re almost always cheesecake.

There’s no particular mystery as to why this is. Super-hero comics are male genre literature. Guys like to look at cheesecake. QED. There are some exceptions to the rule — but they’re usually built around genre exceptions as well. For example, the Claremont/Byrne X-Men made some effort to appeal to YA girl readers through the character of Kitty Pryde. Thus, Kitty got to mostly wear civies, rather than the skintight and/or improbably cut-out costumes that were the lot of her distaff teammates. (Not that the internets are above a certain amount of Kitty Pryde cheesecake of course.)

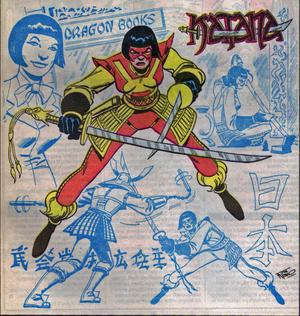

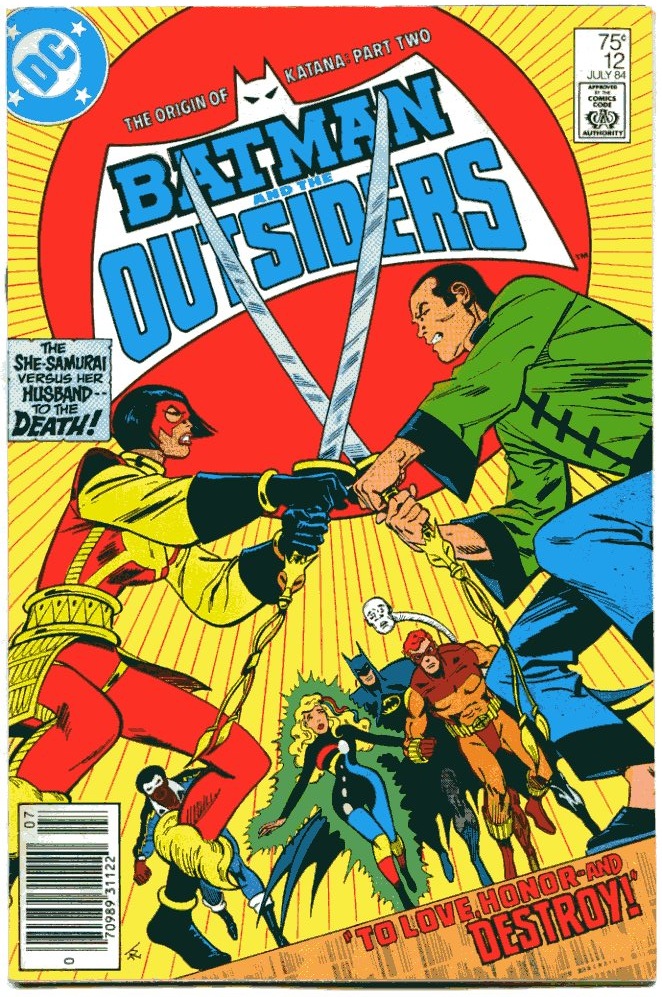

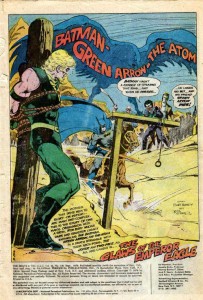

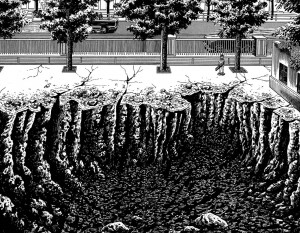

Still, there are a few inexplicable blips. Foremost among them, perhaps, is a minor DC early-80s super-hero who first appeard in Mike W. Barr and Jim Aparo’s Batman and the Outsiders. She was called Katana, and when Aparo drew her she looked, improbably, like this.

That’s a remarkably un-fetishy costume. She’s fully covered, and her blouse isn’t especially tight or revealing: no boob window here. Compared to her teammate Halo, who gets a standard curve-emphasizing form-fitting single piece, Katana seems distinctively to not have gotten dressed with the male reader in mind.

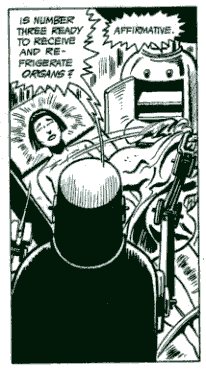

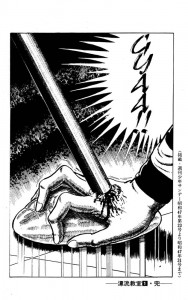

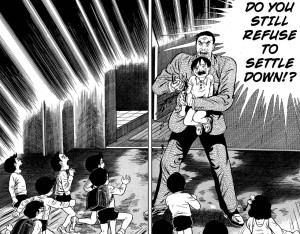

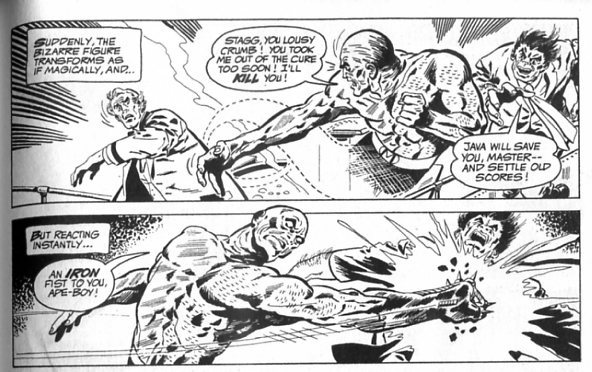

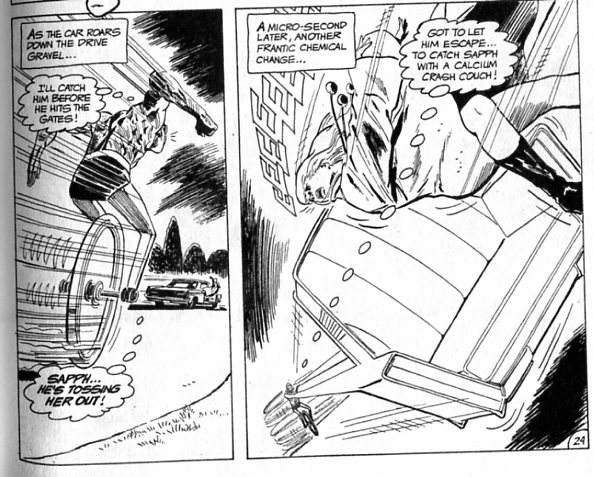

Throughout the series, too, Katana is basically never placed in cheesecake poses or situations. When she gets captured and tied up, for example, there’s none of the bondage imagery you get throughout Wonder Woman’s history. Instead, Katana (or Tatsu, since she’s out of costume in this sequence) is wearing a dowdy hospital gown. She does get stripped down later…but Jim Aparo makes sure we see almost nothing; just a head and shoulders shot from a bizarre ceiling angle, making her look like a twelve-year old boy.

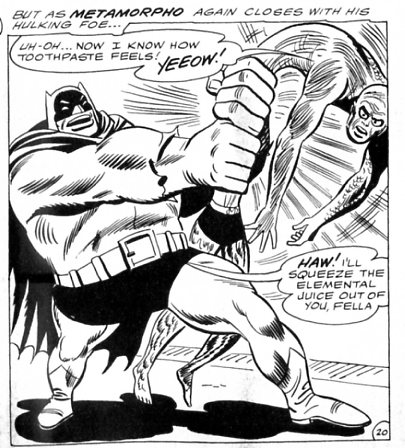

Part of this might be chalked up to Aparo’s particular style; he’s always been more interested in panel composition and shading than in cheesecake for its own sake. But writer Mike W. Barr also played a part in the character’s resolute unsexiness. Katana played the part in the Outsiders that Wolverine played in the X-Men; she’s the bloodthirsty killer with the sharp pointy object, always wanting to dash into danger and slaughter something. While men like Wolverine who play that role are generally just aggressive, the standard script is for women of that type to also be sexually aggressive — a la Elektra, or really anyone else that Frank Miller has ever written. The fact that Katana is Japanese only makes the clichés all the more inevitable; she should be a dragon lady.

But she isn’t. True, she is, somewhat wearisomely, a samurai, since any superhero from Japan has to be either a samurai or a ninja. But she isn’t at all a sexual fantasy. On the contrary, Barr writes her not as a sexual predator, but as a mother. Her tragic backstory involved the death of her husband and two kids, and her closest relationship in the Outsiders is with the amnesiac, innocent Halo, who Katana treats very much as a daughter — going so far as to become her legal guardian. At least through the first couple of years of stories, Katana, still grieving her husband, has no romantic interest at all. In fact, in the two-part origin revelation where Katana’s husband comes back from the dead, Katana actually re-kills him herself in order to prevent him from hurting Halo. The ridiculous vicissitudes of the plot aren’t really worth describing in detail; the point is, Barr goes out of his way to make sure the reader understands that Katana’s primary emotional commitment is to her surrogate daughter first; any men in her life are decidedly secondary.

So, both narratively and visually, Katana deliberately denied the fanboys the flirty cheesecake they wanted. How did they respond?

As near as I can tell, they liked her fine. As everyone from Han Solo to Wolverine has demonstrated, a tinge of amorality does wonders for a hero’s popularity; Katana’s willingness to occasionally kill people certainly didn’t hurt her standing.In fact, in the letter columns, she quickly became a favorite figure; Mike W. Barr would often answer mail as Katana, threatening to show various letter-hacks their own lungs and/or other bits. Here, for example, she’s responding to Mr. Peckham, a correspondent who initially thought Katana was too much like Elektra, but then provisionally changed his mind.

“Dear Michael:

Tell Mr. Peckham he may rest easy, at least “for a few more issues.” When he arrives at a final verdict as to my role as Katana, I will arrive at a final verdict as to the disposition of his internal organs. Perhaps the next two issues will influence him favorably. In the meantime, it might be wise to lay in a supply of paper towels and sponges. Yours, Tatsu.”

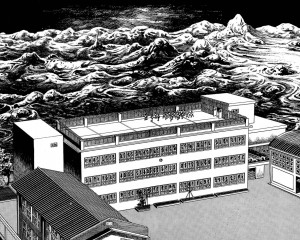

Despite the positive fan reaction, though, Katana never became a major DC heroine. This was probably mostly due to the fact Barr’s letter-column joshing was by far the best writing he did for the series. His actual scripts were watered down versions of the Wolfman/Perez watered down Clarmeont/Byrne X-Men — and, of course, the Claremont/Byrne X-Men were not unwatery to begin with. Batman and the Outsiders was an uninspired teen book melodrama, stuffed with unmemorable villain teams, stiff character interactions, and final page plot twists that didn’t so much twist as sit there blinking feebly in the wan revelatory half-light. Jim Aparo’s art is always worth looking at…but eventually he backed out for a number of less engaging artists, and then there was really no reason to think about the series, much less read it. The Showcase reprint volume is a massive testament to the fact that DC is willing to reprint any damn thing in a Showcase reprint volume.

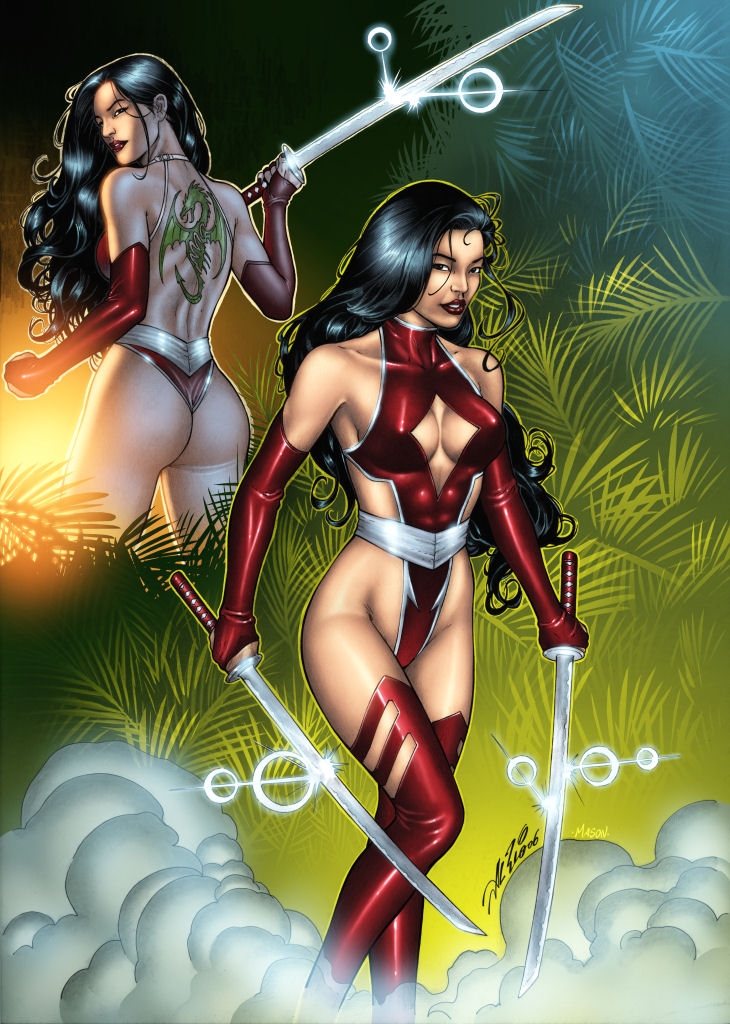

Katana still pops up on occasion — often with a costume redesigned for slightly more va-va-voom. Stil, that hasn’t made her a marquee character. On the contrary, and counterintuitively, she was most successful at the beginning of her run, when, perhaps through an accidental oversight, she looked nothing like a pin-up.

Al Rio reimagines Katana as fanboy wet dream.