This post first appeared on cico3.

______

Law & Order ran a simple formula. Roughly the first half of each episode followed a police investigation (order) while the latter half followed a prosecution (law). One frequent addition to this formula was adding in “ripped from the headlines” stories. This ensured that topical politics were commonly part of the franchise though normally covered only superficially and from a center-right perspective. Yet on occasion Law & Order put out an episode that really captures something sharp, perhaps unintentionally. One such episode is “Burn Baby Burn” which aired on 22 September 2000 and examines an ex-Black Panther who kills a cop in self defense.

“Burn Baby Burn” builds on public sentiment after the NYPD murder of Amadou Diallo in 1999 and acquittal of the cops who killed him earlier in 2000, followed by the NYPD killing ten more people, mostly Black and most notoriously Patrick Dorismond, prior to the episode’s airing. But the headline that most guided the episode was the killing of two cops in Georgia for which former Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee leader and Black Panther Jamil Al-Amin (formerly H. Rap Brown) was arrested and later convicted.

The episode opens with two young Black men finding a white cop shot dead in a hallway outside an apartment. The cop had accidentally gone to the wrong address as part of following up with a witness. Detectives Ed Green (Jesse L. Martin) and Lenny Briscoe (Jerry Orbach) arrive on scene to investigate. The apartment is rented to Selina Watts (Sandra Daley). Watts is a Black Muslim woman who works at an anti-eviction group in Harlem led by Lateef Miller (Clarence Williams III), an ex-Black Panther. Miller is suspected to be the shooter and is taken into police custody by Green at a mosque in Harlem after Friday prayers.

Green and Briscoe question Selina Watts

Miller and his lawyer Leon Chiles (Joe Morton) initially focus on how the police in general and the NYPD and dead officer specifically are racist, and hint they might be framing Miller (this is never explicitly accused). After Green and Briscoe find evidence linking Miller to the site of the shooting, Miller and Chiles switch tactics and present an affirmative defense where Miller killed the cop in self defense. They contextualize this in a long history of racist policing. In response Assistant District Attorney Jack McCoy (Sam Waterson) presents Miller as long advocating the killing of police and attributes the shooting to Miller’s supposed prejudice against white people. The jury finds Miller’s claim of self-defense convincing and acquits him of the murder charge.

The improbability of the result notwithstanding, this is an interesting and quite good Law & Order episode. Much of the time Black liberation and civil rights activists on the various Law & Order shows are portrayed as cartoonish hucksters, people interested in self-promotion whose advocacy for rights and liberation is at least in part disingenuous. “Burn Baby Burn” does not do this. The closest it comes to sloppy white caricatures of Black liberation is in an early scene right after Miller is arrested where he appears in court and shouts that because he is a political prisoner, the Geneva Conventions do not allow for the hearing. Either the writers did not know what the Geneva Conventions are or they wanted Miller to appear nonsensical. Miller’s quiet, measured narration (from Williams III’s truly terrific performance) throughout the rest of episode show the initial courtroom performance to be unrepresentative in a throw-away scene.

The episode lays out Black grievances against racist policing in depth exceedingly uncommon on Law & Order or any other police show, The Wire notwithstanding. After Miller and Chiles switch to the affirmative defense the judge holds a hearing to consider their request to introduce new evidence of the history of police racism. Miller and Chiles are shown partially obscured by many large boxes representing the evidence. The scene begins with the following exchange:

Judge: What evidence are you seeking to admit Mr. Chiles?

Chiles: Evidence of police violence against African-Americans: Abner Louima, the Amadou Diallo murder–

Assistant District Attorney Abbie Carmichael (Angie Harmon): The police in that case were acquitted.

Chiles: Heh. Not in my client’s neighborhood. The Michael Stewart murder, Eleanor Bumpurs, Rodney King in LA, the Fred Hampton assassination in Oakland [sic].

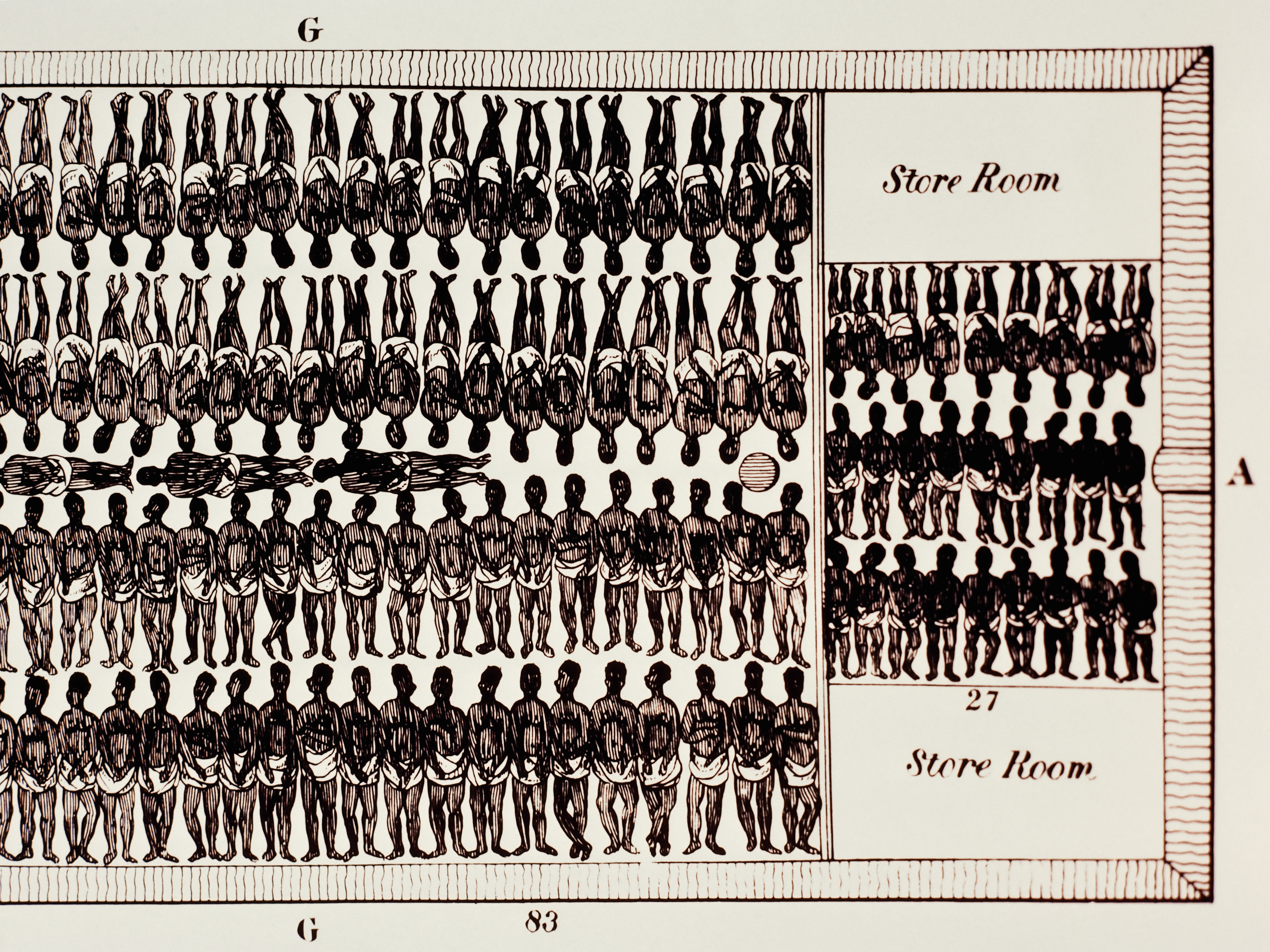

Chiles and Miller behind boxes of evidence of racist police brutality

Cop shows simply do not offer long, historical contexts for police racism. Just as importantly, the episode offers this alongside unambiguous portrayals of police racism and police brutality against Black people. In one example, a white cop points his gun at an older Black bartender and shouts, “If you’re lying to us I’m gonna kick your Black ass!” Det. Green confronts the cop outside afterwards.

Cop: Oh aren’t you a big shot? What are you playing Al Sharpton in front of the brothers?

Green: Hey man I’ll take you anytime. Anywhere.

Cop: Oh like we don’t know who’ll wind up all jammed up outta that. Certainly not the brother.

Green: You say ‘brother’ like that one more time and I swear to god I’mma stomp your ass into the pavement! [Emphases in original]

Cop threatens an elderly Black bartender

This is also perhaps the best character episode for Green. In the exchange above Green has demonstrably justified rage as a Black man against racism, something uncommon in cop shows. He later tells Lt. Van Buren (S. Epatha Merkerson) that, “Lateef’s like a living legend, you know what that makes me.” Green is referring to what James Baldwin described in his 1967 essay, “Negroes Are Anti-semitic Because They’re Anti-white.” Baldwin writes, “We did not feel that the cops were protecting us, for we knew too much about the reasons for the kinds of crimes committed in the ghetto; but we feared black cops even more than white cops, because the black cop had to work so much harder–on your head–to prove to himself and his colleagues that he was not like all the other niggers.” Van Buren assures him, “Oh I know you’re not buying that.” Green kind of shrugs, as if he’s partially thinks this is true. Later in the episode this idea comes back when, after the initial case is not going well for the prosecution, Green says, “I didn’t come all this way to let this guy go.” The episode’s context suggests that “all this way” refers to Green working semiconsciously towards racist ends. Green is caught between being a Black man who would be targeted by the police as part of the general criminalization of Black people and being a cop, a position that does the targeting. This is true in all of Green’s episodes but it is virtually never acknowledged, much less explored.

One of the episode’s most powerful segments comes during Chiles’ questioning and then McCoy’s cross examination of Miller’s former Panther colleague Rolando August (Chuck Cooper). August lays out the history of police violence against the Panthers noting everything from surveillance to infiltration to disinformation to harassment to murder.

Chiles: What impact did these events have on you.

August: They left me pretty cynical about the police.

Chiles: Even after thirty years?

August: Not much has changed. You recruit a bunch of white, high school kids from up in New Paltz to come down and keep order in the hood. That’s how you end up with forty-one shots in some poor Black guy coming home from work.

McCoy tries to isolate Miller by asking why August had not been in touch with him in recent years.

McCoy: “Was that because you no longer wanted to associate with a person who was still committed to violence?”

August: “I promise you sir, his fear of cops is my fear of cops. And his anger is my anger. Every time a police siren pulls up behind me I still get a feeling in my gut they’re gonna pull over, and mess with me!”

McCoy: “Does that mean you could see yourself shooting a cop who came to your door?”

August: “It means I’m tired of being messed with.”

August tells McCoy he’s “tired of being messed with.”

Miller testifies to Chiles about the circumstances of the killing. McCoy’s cross examination consists mostly of gaslighting Miller. Miller asserts that he could see racism in the cop’s eyes and McCoy accuses Miller of something akin to that famous unicorn ‘reverse racism’. Miller, in tears, responds shouting, “It’s my life’s experience!”

Miller is cross examined by McCoy

Chiles then begins his closing argument.

I think you have a very good picture of what the world looks like to Lateef Miller; a man whose suspicions of the police were nurtured by the racism that existed and still exists in this country. A worldview shaped by the political foment of the sixties and then crystallized by current events; a never-ending list of African-Americans that have been attacked or murdered by white police officers.

The jury turns in its vote to acquit. Afterwards, McCoy chats with District Attorney Nora Lewin (Dianne Wiest).

Lewin: Don’t beat yourself up too badly over this one Jack.

McCoy: A guy shoots a New York City police officer in the line of duty and I can’t convict him.

Lewin: Enough of the jury identified with his fear of cops.

McCoy: Used to be fear of cops didn’t justify shooting them.

Lewin: Used to be a lot of things.

It’s worth noting again how uncommon all this is on U.S. television. I suspect the writers still intended to portray this as someone getting away with a murder they should not have. And the show still privileges the points of view of the police and prosecutors. Yet the episode offers context enough for any reasonable people to conclude, “Yes, he was right to be, as a Black person, afraid for his life from the police.” Lewin in the middle of the episode said that Chiles and Miller were “hitching [their] wagon to the anti-police sentiment in the city.” And the episode amply laid out the reasons for that sentiment.

The episode aired to over 18 million viewers initially, this during NYC Mayor Rudy Giuliani’s reign of “broken windows” policing that was much lauded in the local and national media even with the temporarily increased scrutiny that came with Diallo’s murder. In today’s environment with an audience (including white people) significantly more skeptical of prisons and racist policing, thanks mostly to prison abolition groups and authors and more recently the #Blacklivesmatter movement, this episode might read differently than it did at the time. It might read more like it would have in 1968. Miller, a fictional ex-Black Panther, successfully used self-defense to justify his killing of the cop and this is presented alongside descriptions, portrayals and critiques of racist policing. This invokes the Black Panther Party itself which was, after all, originally called The Black Panther Party for Self Defense.