Let me say up front that I loved Man of Steel. Unabashedly. I didn’t realize how much I missed a well-done Superman, someone who is just genuinely a good person, not all broody and conflicted like Batman, nor snarky like Iron Man, but someone who wants to do the right thing, until I was watching the movie and I loved it.

But even in the middle of my love for it, I felt like something wasn’t quite right. The movie was so good, but it wasn’t great. The movie seemed both to love Superman and not quite understand him. Take the ending, where so much of Metropolis is destroyed, so many lives lost, but without any emotional consequences for Superman. I didn’t buy that Superman wouldn’t have at least attempted to move the battle out of town and I surely didn’t buy that Superman wouldn’t have been devastated by those deaths.

But the biggest indication I found that the movie didn’t get Superman had to be when we saw Superman in the church, his head right next to Jesus. This wasn’t the only Jesus reference. Richard Corliss in Time points out the obvious others:

Man of Steel takes its cue from Bryan Singer’s 2006 Superman Returns, which posited our hero as the Christian God come to Earth to save humankind: Jesus Christ Superman. [Script-writer, David] Goyer goes further, giving the character a backstory reminiscent of the Gospels: the all-seeing father from afar (plus a mother); the Earth parents; an important portent at age 12 (Jesus talks with the temple elders; Kal-El saves children in a bus crash); the ascetic wandering in his early maturity (40 days in the desert for Jesus; a dozen years in odd jobs for Kal-El); his public life, in which he performs a series of miracles; and then, at age 33, the ultimate test of his divinity and humanity. “The fate of your planet rests in your hands,” says the holy-ghostly Jor-El to his only begotten son, who goes off to face down Zod the anti-God in a Calvary stampede. You could call Man of Steel the psychoanalytical case study of god-man with a two-father complex.

All these New Testament allusions — plus the image of Superman sitting in a church pew framed by a stained-glass panel of Jesus in his final days — don’t necessarily make Man of Steel any richer, except for students of comparative religion. And as Goyer has noted, “We didn’t come up with these allusions of Superman being Christ-like. That’s something that’s been embedded in the character from the beginning.

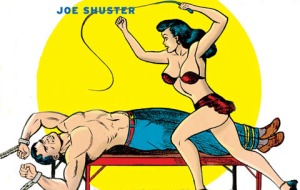

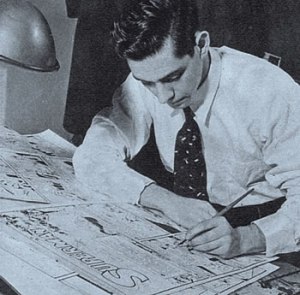

Whoa, doggy. That’s just flat out wrong. Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster weren’t patterning Superman after Jesus. They were patterning him after Moses. A woman has a baby she cannot keep or he’ll die. She puts him in a small ship, of sorts, and sends him off, hoping some other woman will take him in, raise him, and keep him safe. He grows up to save people.

It’s not a perfect match. Moses’ mom lives. He has a sister and a brother who he hooks back up with later. His culture of origin isn’t lost.

It’s not a perfect match. Moses’ mom lives. He has a sister and a brother who he hooks back up with later. His culture of origin isn’t lost.

But losing sight of Superman’s origins in a basket in the bulrushes means the filmmakers miss the importance of some of the very things they’re depicting. And they miss opportunities to make Man of Steel into a richer story, because they’re drawing on the wrong archetype.

Let’s be frank. Jesus makes a bad Superman. There are a lot of reasons why, starting with the fact that no one wants to watch Superman standing around lecturing people, being tortured to death, and then scaring the shit out of his friends by appearing to them after he’s dead (okay, maybe I would want to watch that Superman movie, but it doesn’t scream summer blockbuster) and ending with the fact that Jesus, though a really compelling figure, is compelling for his ideas, not his action adventures.

But the most important reason Jesus makes a bad Superman is that, unlike the other men in the “hidden special child” genre, Jesus’ story has a specific arc and a definite end. And I’m not talking about his crucifixion. What I mean is that Jesus has one battle with his arch-enemy, he wins, and the world is over, the end.

Jesus’ story can be retold and reimagined—a crucial component for a good superhero story. But there is no “Tune in next time for another exciting adventure.” Jesus is a one-and-done hero. When Jesus accomplishes his mission, the world is at its end. If Superman is Jesus and we saw his huge fight with his dad’s nemesis, what’s the plot of the next movie?

But, as luck would have it, even if the filmmakers thought they were making a Christ-allegory, there’s enough of the Moses tale still present to suggest some possibilities for further storytelling. We saw Lara, like Jocabed, entrusting her son to a woman she could not know. There’s not a lot about the Pharaoh’s daughter in the Christian Bible, but both Jewish and Muslim lore flesh her out a whole lot more and, though the lore differs somewhat, both traditions show her radically changed by raising Moses, to the point where she throws her lot in with the Jewish people trapped in her country and forsakes the Egyptians.

It would be interesting to see how Martha Kent might throw her lot in with the superheroes, even though she’s not one, in order to keep supporting her son and his cause. Superman stories tend to leave Martha at home, but the Moses archetype suggests bigger possibilities for her.

I think we unintentionally saw the destruction of the Golden Calf when Superman destroyed the drone. And we saw, constantly, Superman surrounded by people who didn’t quite trust him. All this just serves to remind us that Moses has continuing adventures. He does have a good arch-nemesis in the Pharaoh, with a great backstory that ties them both together in a compelling way that adds to their encounters. Is Moses rejecting the culture, and thus the Pharaoh that saved him? How can the Pharaoh retain his power and authority in his own community and deal with a community with God on their side? Moses has a murder for a righteous cause hanging over his head (and really, the death of Zod in Man of Steel is alarming because the movie has spent so much time arguing for Jesus-Superman. And Jesus doesn’t kill people. But there’s no such problem with Moses.). And then there’s the 40 years in the wilderness. There’s a lot of ground to cover, stories to be told. Things you could add or take away or retell in countless ways. The fact that at least three religions already do so proves it’s a rich story that stands up to the type of reuse our superhero stories get.

The biggest difference between Moses and Jesus, one with important implications for the Superman story is that, while Jesus can go anywhere people are—earth, Heaven, Hell—Moses never entirely fits in with the people he’s leading. He wasn’t raised with them, he wasn’t an adult among them at first (remember, he runs off and lives in Midian for forty years), and he can’t go with them into the Promised Land. It’d be interesting if these were the people of Earth. But imagine the story you could tell if these were the Justice League. What would it mean if Superman were leading them toward a goal he could never meet?

I saw referenced multiple places that Man of Steel was yet another movie that attempts to tell 9/11 with a happy ending. Okay, so if Superman can be used to talk about big tragedies people are still trying to grapple with, why not more explicitly let Superman grapple with the unimaginable tragedy of the destruction of his people in ways that mirror how Jewish people have wrestled with the Holocaust?

I’m not arguing for a one-to-one mapping. Obviously that wouldn’t work. But there are writers who could pen a compelling story—because they know that story—about a guy who, as far as he knows, is the only person in his culture left, who must wonder if he resembles his grandfather or whether he got his love of science from his aunt, who must wish he knew old folk songs or what the people in his family’s neighborhood ate at holiday meals, and who can’t ever get complete answers to those questions.

And then, what happens when Kara shows up? Do you rejoice in the found family member? Do you find her presence a sharp reminder of the rest of your loved ones’ absences? Of their ultimate fates?

Superman can have hope because he’s corny Jesus-dude made of hope or he can have hope because the alternative is to give into despair. The second choice makes for a more real movie, and one that, I’d argue, is truer to Superman’s roots, both mythically and in the lived realities of his original creators.

But the thing I find most fascinating and appalling about taking something with its roots in Moses and declaring that its roots were in Jesus all along is that this is such a common approach—not to superheroes, but to theology—that there’s a word for it: Supersessionism.

The belief that the new covenant between Jesus and his followers supersedes the old covenant between God and the Jewish people is fundamental to most forms of Christianity. Even if Christians don’t know the term, it’s the reason we eat cheeseburgers. And it’s an incredibly tender sore spot among Jewish people, who aren’t that excited to hear all about how, when God said he was keeping a perpetual covenant with the children of Israel, he meant “perpetual until some better people come along.” Jewish scholars and theologians have argued—and rightly so, I think—that the Christian belief that Christians now have the special relationship with God that supersedes the Jewish relationship is an important part of the foundations of anti-Semitism (because, in part, it implies that God’s fine with whatever terrible things Christians want to do to Jews, because God doesn’t love them best, or at all, any more).

Superman isn’t a Jewish myth, but he’s a cultural figure with strong Jewish roots—created by two Jewish guys, given an origin story that draws heavily from one of Judaism’s central figures. Neglecting those roots and grafting on Christian ones instead is problematic. It makes for a less compelling story (like I said, if Jesus/Superman has defeated Satan/Zod, what can happen in the next movie that still keeps Superman a Christ-figure?), it neglects the rich mythology Superman’s creators drew from, and it perpetuates a troubling theological stance.

But I think the worst thing is that it indulges its majority Christian audience in this country in a lie we often tell ourselves without realizing—that Jesus is the center of all things and we, being close enough to the center, should be the people around which the whole country revolves; all stories are our stories or can be taken and made to be. In the end, using Superman to reinforce Christian supremacy in the United States probably isn’t going to ruin Superman. But it is a lie that comes from and leads to ugly places. And it’s a shame to see it at the heart of Man of Steel.

______

Betsy Phillips writes for The Nashville Scene‘s political blog, “Pith in the Wind.” In her spare time, she makes up spooky stories. Her fiction has appeared in Apex Magazine and Qarrtsiluni.

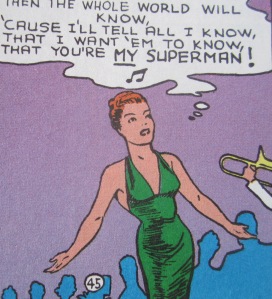

First illustration unknown artist; 2nd from Grant Morrison/Frank Quitely All Star Superman”