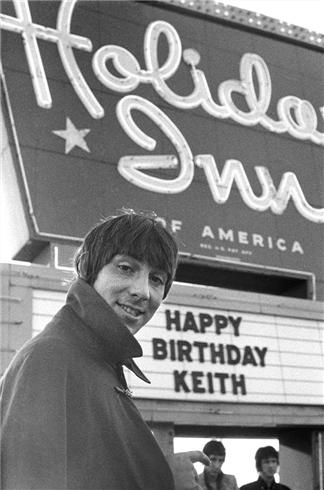

Keith Moon would have turned sixty-eight on August 23rd of this year — a slightly mind-boggling thought, if only because it’s so difficult to picture him as an elderly person.1 But I wish that I could imagine such a thing, because few people that I have never met hold such a place of affection in my heart. What is it about Keith Moon that can inspire such feelings of warmth, delight and sorrow in me, more than thirty-five years after his death? What is it about his extraordinary musical personality that strikes me as so compelling and charismatic? In honor of Keith’s birthday, I’d like to beg your indulgence and spend a little time ruminating over these questions here.

I can distinctly remember the first time that I became aware of Keith Moon’s existence. It was the summer of 1978, and I was nine years old, sitting in the living room of my family home in Cardiff, Wales, watching Top of the Pops on the BBC. In the age of the Internet, it can be shocking to recall just how limited the media outlets for rock music once were, particularly in Britain. But the Thursday night screening of Top of the Pops provided fans with what was at the time a very rare opportunity to see their heroes in action — perhaps the only such opportunity for a younger viewer like myself who was unlikely to see a live show. Indeed, for much of my childhood and into my early teens, watching Top of the Pops was a required weekly ritual, as well as the fodder for intense schoolyard analyses the following day. So it was that on this particular July evening I happened to catch one of the first British broadcasts of the promotional film for “Who Are You?”

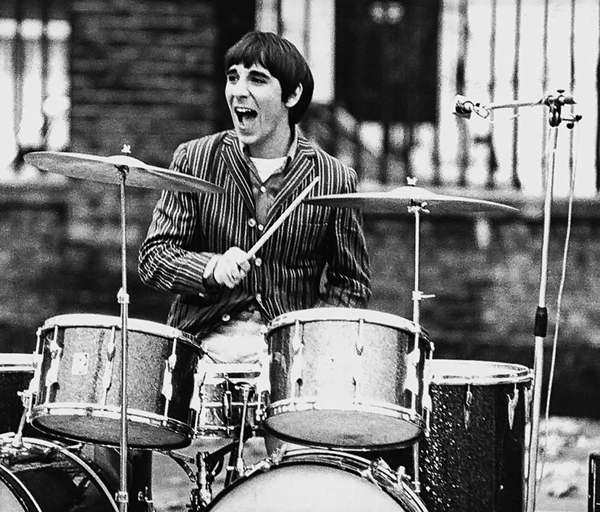

I was not then an admirer of The Who — the most popular album at my junior school that year was the soundtrack to Grease — and even today I don’t rate “Who Are You?” as much more than a late reach for past glories: “Won’t Get Fooled Again,” again, only not as good. But that night in 1978 was the first time that Keith Moon surprised me into laughter. His round face framed by large earphones ludicrously secured to his head with industrial tape, Keith played with a dynamic kineticism quite unlike anything that I had seen before. Other drummers, even the least sedate, tended to stay in one place in their seats, whatever their arms and legs might be doing; this makes good sense from the point of view of technique, since ideally one wants to keep all parts of the drum set within reach at any given moment. However, Keith’s style seemed to require movement throughout his entire body, with abrupt lurchings off in one direction across his massive kit, and then hurried rolls back the opposite way, all the while striking out in every direction like a monkey in a gnat swarm. He didn’t hit his cymbals so much as pounce on them, roaring. With his puffed cheeks and bulging eyes he might have been trying out for the part of the villain in a children’s pantomime — one of those melodramatic performances intended to evoke giggles rather than fear — and I think it probably was to his facial expressions that my nine-year-old self most strongly responded, rather than his percussive prowess. I have since watched this clip many times and have seen and heard a great deal more in it than I was capable of discerning initially. But my childhood intuition that this funny, crazy drummer played an essential role in distinguishing his band from the competition has only been re-confirmed.

The song begins by creating an atmosphere of sonic suspense. Townshend’s jittery licks flicker across a stuttering synthesizer sequence, setting the stage for a gentle but insistent chorus of high harmonized voices that repeatedly pose the question of the title over the nervous chatter and splash of Keith’s hi-hat. The combination establishes a mood of anticipation, whetting our appetite for the inevitable entrance of the band at full bore. But in Jeff Stein’s film, we can see that Keith’s hi-hat has not been placed, as in a traditional set-up, tucked inside the main structure of his drum-kit, but away beyond a flank of tom-toms. This unusual placement reflects Keith’s relatively infrequent use of what is, for most drummers, a central element of the rhythmic arsenal, and serves as a neat reminder of just how idiosyncratic his approach was. But Keith’s set-up also has the effect of requiring him to lean out over his instrument towards the camera and the other musicians; from his first appearance in the clip, then, we know that this is a drummer who will refuse to disappear behind his drums. No mere timekeeper, his presence contributes as much to the theatrical, visual appeal of the band as to the overall sound. In fact, as he glances back and forth at his bandmates, Keith seems to be vying as much for their attention as for the gaze of the camera. The impression that Keith is reflexively performing for his fellow performers is confirmed as the film progresses through sequences in which we watch him mugg and gurn in an effort to amuse a cranky Pete Townshend, and a typically taciturn John Entwistle, while ostensibly recording handclaps and backing vocals.

Keith’s comic antics work, of course; neither Townshend nor Entwistle can keep a smile off their faces for long around him. But behind the laughter, Keith’s troubles had become a source of desperate anguish for those who loved him, and the extent of his problems would soon be obvious to the rest of the world as well. For the “Who Are You?” film depicts the last occasion that Keith Moon entered a recording studio with his bandmates. He would play only once more with The Who, on May 25, 1978, on a soundstage at Shepperton, in a sub-par performance recorded for the movie, The Kids Are Alright. He died a little more than three months later — only a few weeks after I saw him on television for the first time — as a result of what was probably an accidental overdose of the barbiturate Heminevrin (a medication that he had been legally prescribed as an adjunct to treatment for chronic alcoholism). With the benefit of this hindsight, Keith’s performance in the “Who Are You?” film is inevitably as poignant as it is captivating: impossible to watch without an awareness that the end is near.2

The band had opted to re-record the song for the film-shoot rather than merely mime, and while this decision unquestionably adds to the interest of the clip, Keith’s drumming is far from flawless. In the context of his looming fate, these audible errors inevitably resonate with ominous significance. For example, the middle section of the song contains a kind of mini-crescendo, culminating as Roger Daltrey cuts loose with his best Acton Town blues-howl: “Whoooooo are yoo-oo-oo!” This false musical climax is then followed by a slightly unexpected shift into another quiet instrumental passage. But if you listen to the film sound track carefully, you can hear Keith momentarily forget this pianissimo-fortissimo-pianissimo structure, instead taking off immediately after Roger’s bellow with the snare and bass drum rhythm that actually drives the final section of the song. He stops abruptly, realizing his error, to re-trench sheepishly behind a wash of cymbals. (Some might consider it fanciful to suggest that cymbals can convey embarrassment; nevertheless, that is what I hear. Even Keith’s mistakes as a drummer can be powerfully emotionally expressive.)

Indeed, it is painfully apparent by comparison with earlier footage and recordings that in musical terms, at least, the drummer in the “Who Are You” clip is only doing a passable impression of himself: Keith Moon playing “Keith Moon.” I don’t evoke this mimetic paradox simply to be clever; as it turns out, the idea that Keith’s personal identity became a horribly demanding role — one that exhausted and ultimately consumed its creator — is actually a recurrent theme in the posthumous mythology that has grown up around him.3 Less commonly noted, however, is the fact that this symbolic concept or role of “Keith Moon” has now managed to detach itself almost entirely from the creative category of “musician,” instead coming to denote a whole lifestyle based on endless, reckless hedonism: an anarchic, destructive, and yet apparently insatiable capacity for sensual pleasure and alcohol-fuelled excess. It seems to me central to an understanding of the man’s misfortune to note the extent to which this idea of “Keith Moon, the craziest guy in rock” splits off from and ultimately obscures the notion of “Keith Moon, drummer.” I’d go so far as to suggest that Keith’s spectacular percussive gift remains under-appreciated in some quarters as a consequence of this symbolic division. That’s why I want to celebrate Moon the Musician today, and not Moon the Cartoon-Loon, wrecker of hotel rooms and serial smasher of television sets.

Keith Moon was both the youngest member of The Who and the last to join, at the age of seventeen, in 1964. Daltrey, Entwistle, and Townshend had all known one another since high-school, and had already been playing together for more than a year under the name of The Who (and The High Numbers), with more than one different musician in the drum seat. Keith would joke later that his status as drummer was never made official: “I’ve just been sitting in for the last fifteen years,” he deadpans in The Kids Are Alright. “They never actually asked me to join the group. I knew it by instinct.” Like all good jokes, this one is illuminating at both a conscious and unconscious level. On the one hand, Keith’s place in The Who is presented as entirely natural, a fit so self-evidently perfect that it did not even require articulation: instinctively correct. This perspective accords with the majority verdict of rock historians everywhere, most succinctly summed up by Tony Fletcher in his statement that the “band … never gelled before it found [Keith, and] never gelled again after it lost him.” On the other hand, the joke emphasizes Keith’s sense of himself as not quite “part-of,” as standing a little outside of a previously established fellowship. The self-deprecatory claim to be merely “sitting in,” while painting his position as far more precarious than it actually was, hints at a deeper sense of insecurity.

Still, even if Keith was never officially invited to become The Who’s permanent drummer, in the years since his death his bandmates have openly allowed that he brought something essential to the mix (although these acknowledgements would come only after a lengthy period of denial, the sheer extent of which may indicate just how painful Keith’s loss was, particularly to the group’s leader, Pete Townshend). In one of the most generous of these statements, Roger Daltrey has remarked that, whatever they may have called themselves at different times, “The ‘Oo were not really The ‘Oo” before Moon’s arrival.4 I’m tempted to go further; in my opinion, for at least the first year of their career, the most innovative, ear-catchingly distinctive element of The Who’s sound is to be found in Keith Moon’s contribution. At the outset, The Who is a band driven from the drum seat.

Consider, for example, the first single, “I Can’t Explain.”

As many have observed, the basic riff owes a good deal to prior records by The Kinks, although the lyric is pure Townshend: a teenage boy, “dizzy in the head,” struggles to describe surging, narcotically powerful emotions that he cannot precisely name or articulate. The rapid mood-swings of this archetypal Mod-figure convey a kind of adolescent urgency to which the stabbing chords and upbeat tempo of the song are entirely suited. But in other ways the music and lyric are less than obviously matched. For while the singer cannot distinguish love from confusion, telling us that he feels “good,” “sad,” “blue” and “mad” all at once, the music is much less emotionally complex. It’s a blast of exuberance that ultimately transcends the theme of frustrated adolescent desire to express sheer, light-hearted joy.

This feeling of exuberant joy owes more to Keith’s drum part than any other single element of the track. Tony Fletcher writes that “I Can’t Explain” “would only have been a great song without Keith Moon’s input, never a great record,” an observation I would extend to cover almost everything The Who put on an acetate in this very early period.5 The importance of Keith’s contribution is more apparent if we first consider the song in its immediate musical context of mid-60s British pop. I am hard-pressed to think of any prior recording from that era that leads so prominently from the back. The song is predominantly in 4/4 time, but the basic “1-and / 2-and /3-and /4-and” rhythm is established and sustained throughout not by the drums, but by the guitar. “I Can’t Explain” thus reverses the conventional arrangement of most beat-driven pop of the era; rather than stringed instruments and vocals playing relatively intricate lines around and on top of a simple rhythmic back-drop created by, say, a bass guitar and snare drum, we have a series of ever-changing and intricate drum-fills playing around and behind the rhythmic spaces delimited by the guitar and vocals. Moreover, when the time signature of “I Can’t Explain” alters slightly at the end of the second and third verses, the steady 4/4 giving way to three heavy beats played by the band in unison to emphasize the vocal (“I know what it means, but…”) it is the drums that step forward into the pause created by this overall rhythmic shift, with a double burst of three sixteenth-notes on the snare, announcing the transition from verse to chorus. Such moments in which a drummer steps forward at the end of a bar or phrase are, of course, common enough in many great early rock songs — one might think of the rapid-fire triplets that end each verse on Elvis Presley’s “Jailhouse Rock,” for instance. But D. J. Fontana brings “Jailhouse Rock” to a startling dead-stop at those moments, while the effect of Keith’s little break is more like that of an intake of breath — a percussive gasp for air that precipitates not a sudden stop but rather a series of even more complicated drum rolls played on the entire kit.

The distinctive elements of Keith’s drumming — most particularly his use of the instrument as a vehicle for emotional expression and musical punctuation rather than as a pace-setting and time-keeping device — are more apparent in an early live performance of this song on the TV show Shindig than they are on the original studio recording.

In the studio we find him tapping with relative restraint on the hi-hat, playing the basic four-four rhythm at double-speed. On the Shindig performance, by contrast, Keith’s hi-hat is relatively inaudible (and played almost entirely with his foot — he rarely if ever strikes it with a stick). In place of it’s insistent tick-tick-ticking, he adds an almost constant wash of sound from a ride cymbal. He would increasingly adopt this distinctive style in live performances, producing a continuous wave of noise with his cymbals from out of which the toms, bass drum and snare burst forth explosively.

Something else we can observe in this Shindig appearance is the way Keith draws the gaze of the camera, even in the relatively short space of this song. Most early TV appearances of pop-groups display a fixation upon the singer as the primary point of visual interest, with only occasional cutaways to other musicians (particularly when they sing a backing vocal). Drummers, notoriously, rarely catch the focus for long. This performance starts out as if governed by a similar directorial policy. The first close-up is of Roger, desperately struggling to project the image of Shepherd’s Bush hardnut while actually conveying all kinds of self-consciousness and anxiety in his stiff, awkward body language. The second close-up is of John, singing accompaniment. The camera cuts back to Roger again, and then finds Keith, momentarily. We revert to brief shots of Roger and John, but then the camera switches back to Keith almost if in a double-take: “wait a second, what about this guy!” (Meanwhile, poor old Pete still hasn’t received a look-in.) This time the shot lingers over Keith for slightly longer before cutting away, and when it returns to him for a third close-up, as the song cycles into the first iteration of its chorus, it’s clear that he has won the battle for attention. From this point on, he gets at least as many close-ups as the front man, and even when the camera pulls away on the final chords for a shot of the whole band, it’s Keith who catches the eye, twirling his stick and pointing at us from the side of the frame.

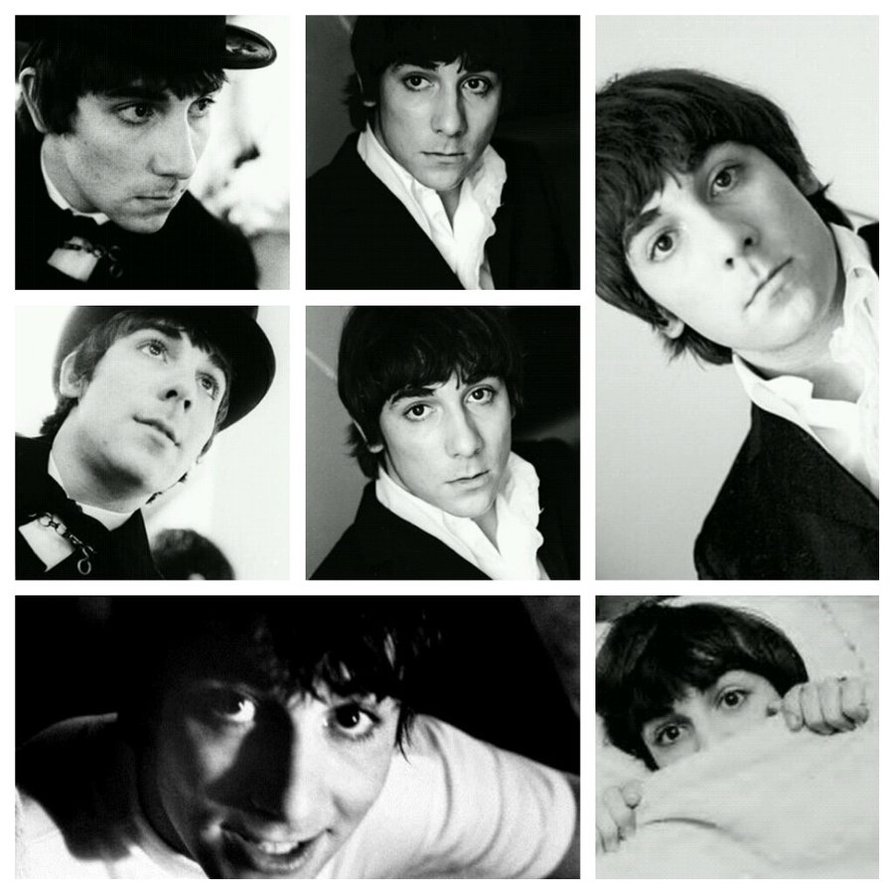

It probably doesn’t hurt that at this stage of the game he is by far the cutest member of the band, with his boyish features, wide, doll-like eyes and jet-black hair. His uber-stylish mod sweater with the target design and his animated facial expressions also contribute to his overall appeal. But he also displays another kind of seductive charisma, here: the charisma of his unique musical style.6 He approaches his instrument with such casual, loose-wristed abandon, his sticks whirling and turning like batons in the hands of an ambidextrous orchestral conductor as he improvises his rolls around the metronomic rhythm-pattern established by Townshend’s guitar. You need look no further than this clip for a definition of sprezzatura; it’s an effortless genius, spellbinding precisely because it seems so unlabored. (There have been and continue to be many theatrically expressive and talented drummers, of course. Stewart Copeland has a cat-like, delicately pouncing violence to his cymbal-strokes; Tony “Thunder” Smith can project an innocent glee while playing like a demon; Terry Bozzio can ham it up while hammering it out. But still, I’ve never seen anyone, before or since, who moves at the kit quite like Keith Moon.) No wonder that once the Shindig camera-crew notices him they are compelled to return to him, even during the guitar-breaks.

But importantly, Keith is selling the song here every bit as much as he is selling himself. To elaborate on that observation of Tony Fletcher’s, it’s not just that Keith’s performance makes the song great; it’s that he plays this competent but slightly derivative pop-song as if it’s great — as if playing drums behind Pete’s riff were not merely an act of musical accompaniment, but one of the most exciting thrills imaginable — and in the process he goes a good way towards winning us all over to his own belief in the material.

On this and other primal recordings (such as second single, “Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere,”), Daltrey, Entwistle, and Townshend sometimes sound as if they are struggling to keep up with the button-faced little dervish who had unexpectedly answered their cattle call and then quite literally beaten the available competition into submission. But by the release of third single, “My Generation,” the band has started to figure out how to make more measured use of its strengths. Townshend fully embraces the role of time-keeper, with his brazenly simple two chord riff, around which Keith’s bass drum and snare thump and pop like fireworks — while the main instrumental break is carried (unusually and famously) by John Entwistle’s teeth-rattling bass guitar.7 Townshend’s willingness to keep the beat and allow his astonishing rhythm section — and particularly his drummer — to play more expressively proved to be the key that released The Who’s signature sound, allowing the band to stand out from the crowd of guitar-fronted groups that had formed in the wake of The Beatles’ success. Keith continues to play the part of a lead instrumentalist in later singles such as “Happy Jack” and “I Can See For Miles,” while the stringed instruments essentially keep time; and even as Townshend grew in confidence and technique as a songwriter, he would continue to leave room for Keith to break out in many of his most important compositions. Songs like Tommy’s “The Amazing Journey” and Quadrophenia’s “The Real Me,” for example, are fundamentally built around the concept of the thunderous, heart-quickening drum fill.

Within the basic parameters of the late 20th century pop group, such a close alliance between a guitarist and a drummer might be considered relatively unusual. But the complementary nature of Moon and Townshend’s personalities is clear, even in offstage interviews. Thrust by his ambition into the position of spokesperson for the idea that pop music could be “art,” Townshend, by his own admission, can sound glib and pretentious when interviewed alone; but with Moon at his side, he became half of the funniest comedy duo in the history of British rock & roll, a kind of musical Rik Mayall to Moon’s madcap Adrian Edmundson (the Russell Harty interview segments interspersed through The Kids Are Alright provide the best instance of this double-act to have survived). But obviously it was as a musical collaboration that the bond between the two men expressed itself most strongly. In fact, I’m inclined to regard the relationship between Pete and Keith as one of the great musical love affairs of the era — right up there with the romance between Lennon and McCartney or Jagger and Richards — even though Keith never shared a writing credit.

Their creative intimacy is already apparent in live footage from the earliest days of the band; for example, at the 1965 National Jazz and Blues Festival in Reading, musical transitions and changes of volume and tempo are usually presaged by an exchange of glances between Pete and Keith. But by the time of the Isle of Wight show in 1970, the two men can barely take their eyes off each other. During the more exploratory stretches of improvisatory jamming they are clearly exchanging visual as well as aural cues in order to regulate the rise and fall of the musical dynamic. Their gazes regularly interlock, and often Pete will step right up to the drumset, as if playing to Keith alone. Still more often, you can see him playing with his head turned over his shoulder, away from the crowd, as if to keep his manic collaborator always in the corner of his eye. Aside from occasional attempts to engage Entwistle by making him laugh, Moon generally returns Townshend’s look; and when Pete’s focus is elsewhere (as, for example, when Townshend attempts to talk to the audience between songs) Keith constantly interrupts him with a stream of comments and rude noises. It would be easy to interpret these interjections as a symptom of Keith’s relentless need for the spotlight, but often it strikes me that he’s trying to get Pete’s attention at least as much as that of the audience — rather in the manner of a boisterous younger sibling seeking the approval of an adored older brother.

The members of The Who have often stated that they considered themselves better as a live-act than a studio band, and the onstage rapport between Pete and Keith — almost impossible to recreate in studio conditions — may well be part of the reason this assessment carries some weight. Certainly, it would be easy to point to many terrific live performances by the band that foreground the dynamic between Pete and Keith, and which also leave the studio recordings of those same tracks in the dust: the electrifying version of “My Generation” at the Monterey Pop Festival, for example, or the almost religiously enthusiastic rendition of “A Quick One” from the Rolling Stones’ Rock and Roll Circus. But I think the quintessential clip — perhaps the first one I would show to someone if attempting to win them over to Keith’s playing — is the performance of “I Don’t Even Know Myself” from the Isle of Wight concert.

I should admit upfront that as a musical composition, this song isn’t actually that strong. The riff is almost echt-Townshend — too close to things we’ve heard him do before (the chords are very similar to those of “The Seeker”). The lyric, too, is a bit of an exercise in Pete’s default mode of bitter alienation. Some of the lines slide from the lazily composed into the downright ludicrous (“C’mon all of you big boys/ C’mon all of you elves!”). But none of these flaws matter to Keith. It’s another classic from the pen of Pete Townshend, as far as he is concerned, and at this show he plays it with the same enthusiasm that he would bring later to such sublimely perfect songs as, say, “Bargain” or “The Punk and the Godfather.”

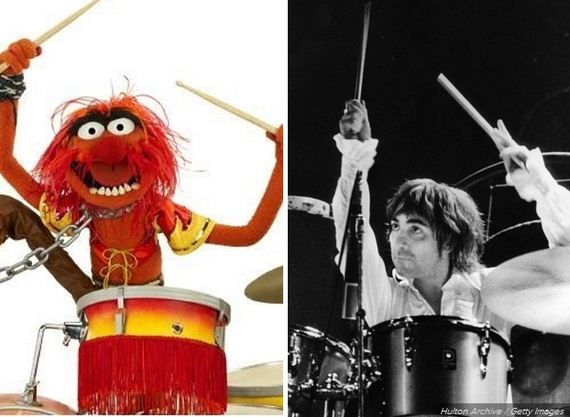

It’s apparent that he can barely contain himself during the introduction, which involves a relatively quiet interplay between Townshend’s guitar and Daltrey’s harmonica; he sits and grins and spins his sticks like a majorette before leaning back on his stool (it’s more of a seated-limbo movement, actually — an inch further and he’d fall right off his perch), and then swoops forward to cut loose at full power as soon as the occasion permits. The first verse comes crashing to an end on a series of left-to-right drum rolls, each one of which he ends by pulling a face at John Entwistle from behind his crash cymbal, like a child playing peek-a-boo. The song then enters a quiet passage that he augments with an erratic clip-cloppity pattern on a woodblock, looking for all the world like a mad scientist gloating over his latest discovery. The song repeats this structural pattern (loud verse, quiet chorus) and Keith repeats his moves: making silly faces at John, rocking dangerously, and then gleefully tapping his wood block while shaking his head and rolling his eyes like Animal from The Muppets. (If any single rock-drummer served as an inspiration for Animal, it surely has to have been Keith?) And then we reach the instrumental break. Briefly locking eyes with Pete to take his cue, Keith’s excitement now knows no bounds. Now he can really make a noise.

The camera angle shifts so that we are positioned behind Keith and so have an interesting perspective on his technique here — if technique is even the correct word. You can see, among other things, how often his right arm flails across his body to strike repeatedly at two cymbals that are positioned on opposite sides of the kit. (The first time I showed this clip to a drummer friend of mine he laughed out loud at this; he found it at once breathtakingly audacious and wildly counter-intuitive. “I’d never even think to just bash away at my cymbals like that,” he said, “but if I were going to do it, I wouldn’t set them up that way. It’s sheer madness!”) Against this near constant metallic crashing, he then sets up a rapid, falling pattern of double stroke rolls with his feet (he’s playing with two bass drums, which allows him to thump out multiple low “notes” far more rapidly than a single bass drum set-up will permit). The overall result is just inches away from chaos, a dance with disaster, the sound of a Premier drum-kit falling down a moving staircase, but somehow managing to do so in time. And then, as the break comes to an end, and the entire band pauses momentarily, Keith cannot stay in his seat. He jumps to his feet, waving his right arm in the air in a triumphant salute … and accidently tosses away his drumstick. (The precise moment occurs at about three minutes and twenty seconds into the song, if you want to check it out, and is clearly unintentional — though, of course, Keith was prone to throwing his sticks around deliberately at times, too.). The stick arcs and drops somewhere behind the kit but almost before it has even hit the stage floor, Keith passes his other stick from his left hand to his right, and (still standing) strikes his right hand cymbal — quite literally without missing a beat. He obviously has plenty of other sticks stashed nearby in case of this eventuality, and has a new one in his left hand before he has even sat down.

No one else in the band even notices.

I once showed this clip to another friend, who happens to be in a 12-step program. We paused to rewind the “stick toss” incident a couple of times, both of us marveling at the combination of ebullient genius and unforced error, not to mention the smooth rapidity with which Keith recovers from his mistake, his obvious preparedness for it, and the blissful obliviousness of the rest of the band to this entire mini-drama. “Now that,” said my friend, “is functional alcoholism!”

It was not intended as a patronizing or reductive observation; he spoke in admiring, even wistful tones. But I winced a little, nonetheless. Because yes, of course, Keith is clearly pretty loaded — probably on more than one substance — during this performance.8 And to acknowledge this fact is, among other things, to acknowledge that my desire to discuss Keith’s musicianship without becoming distracted by his legendary hedonistic persona is finally impossible. The reason that this performance is so exciting is because it feels like it is teetering on the edge of chaos; but it feels that way precisely because it is teetering on the edge of chaos, just as Keith himself is teetering drunkenly on the edge of his stool. He doesn’t fall off, here. But there were nights when he did — perhaps most legendarily at the Cow Palace in 1973, when he passed out twice, and found himself replaced on the second occasion by a nineteen-year-old named Scot Halpin, pulled almost at random from of the audience by promoter Bill Graham (and that is surely as Punk Rock as it gets). So if it is true, as I believe, that the wild legend of “Moon the Loon” has tended to overshadow the critical reputation of Moon the musical genius … well, Keith himself must bear the greatest burden of responsibility for that fact.

My point is not simply that Keith was a genuinely wild and crazy guy, after all, but — more sadly — that Keith himself seems to have valued his lunatic status more highly than his percussive abilities. How else can we explain the fact that on his only solo album, the critically reviled Two Sides of the Moon, he does not even play the instrument that propelled him to international fame and success, choosing instead to croon ballads in an atmosphere of soused self-indulgence like a bad karaoke wannabe? Indeed, Two Sides of the Moon is so inexplicably and unnecessarily unlistenable that it raises the question of whether Keith radically misunderstood the nature of his own gifts.

Alternatively, our general comprehension of the kinds of neuroses that drive addictive behavior may leave us better positioned to recognize something less obviously apparent at the time: the possibility that Keith’s investment in the role of “Moon the Loon” was rooted in more profound problems of self-esteem. If so, then the lesson of Two Sides of the Moon is not that Keith really wanted to be a lounge singer, but that being who he actually was — one of the most exciting, innovative, and original drummers in the rock and roll pantheon — was not enough for him. His inability to take lasting comfort in the prodigious talent for which others so freely adored him may now strike us as the most painful aspect of his tragedy. Although capable of winning the love and affection of thousands of fans, the all-too-familiar kernel of his story may simply be that he did not like himself very much.

I don’t wish to conclude with these perhaps too-pat psychologistic claims, however. Suffice it to say that, like all of us, Keith clearly knew, and caused, his share of pain. But in the distillation of the life that we now have left — in the body of recorded work — the dominant mood is anything but tragic. As the critic James Wood has written in a wonderful tribute to Keith’s musicianship:

it could be said, without much exaggeration, that nearly all the fun stuff in drumming takes place in those two empty beats between the end of a phrase and the start of another … [and] whatever their stylistic differences, the modest and the sophisticated drummer share an understanding that there is a proper space for keeping the beat and a much smaller space for departing from it, like a time-out area in a classroom. Keith Moon ripped all this up. There is no time-out in his drumming because there is no time-in. It is all fun stuff.9

In other words, if Keith wanted (absurdly, against all logic) to “have a good time all the time,” then he managed to express that desire not merely in the antics of his daily life, but in the very substance of his art. Of course, “have a good time all this time” is perhaps not the most sensible life-plan, since it is impossible to realize. It represents a child-like impulse, at best, and a childish one at worst. But few professions have been more dedicated to trying to pull off this impossible project than that of the rock-star. And maybe that, as much as anything else, is why Keith will always remain a contender for the title of “Rock’s Greatest Drummer” — because his unique style in some sense embodies the central hedonistic edict of the musical culture from which it emerges. Outside of a pop-song, we know, no one can have a good time all the time. But inside one … that is when it really can be all fun stuff, all the time. I will always love Keith Moon’s drumming for suggesting this possibility.

_____

I am grateful to Noah Berlatsky, Anthony DeCurtis and Loren Kajikawa for their comments on an earlier draft of this essay.

____

1. This could just be a sign of my own creative limitation, but many people who knew Keith personally have also reflected on the difficulty of imagining him growing old.

2. What for fans is merely poignant must remain painful for those who knew Keith well; and watching the bright-eyed percussive wunderkind of the 1960s transform into the bloated melancholy clown of the later 1970s was surely horrifying, up close. Tony Fletcher captures the anguish of several of Keith’s friends in his highly recommended biography, Moon (HarperCollins, 2000).

3. Consider, for example, John Entwistle, cited in Fletcher, 501: “Of course he was a good actor … he’d been acting at being Keith Moon all those fucking years.” Also worth mentioning is Keith’s own oft-cited description of himself (even as his skills began to slide) as “the best Keith-Moon-type drummer in the world.”

4. In contrast to Roger’s frequent expressions of warmth, Pete is often inexplicably harsh about Keith in interviews, even in recent years. For example, in a 2011 documentary about the making of Quadrophenia, he opines that he didn’t think Keith was actually a very good drummer. I’m inclined to see this tendency charitably, as a sign of Townshend’s residual grief manifesting as anger — but sometimes his unpleasantness about his former collaborator can be quite shocking.

5. Fletcher, 117.

6. In an early draft of this essay, I wrote “the charisma of musical technique” before deciding that “technique” was not quite the word I wanted. I don’t want to get into a long discussion here about Keith’s technical limitations — you can check out the comments below any number of YouTube videos to find people insisting upon them — but I should perhaps say that I am fully willing to concede the point that Keith is not a “technically accomplished” drummer in the way that phrase is usually employed by practicing musicians. But this fact, for me, only makes his drumming more interesting. One of the most remarkable things about Keith Moon is that he can achieve so much, viscerally and emotively, while making mistakes that most drummers strive to eliminate. In any number of recordings you can hear him accidentally clicking his sticks together or striking his rims in the middle of a roll. Sometimes you can hear him losing “the beat” altogether — even in the midst of a performance that somehow remains utterly dazzling. (Check out the isolated drum track from “Won’t Get Fooled Again,” available on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vnVjpymrbIY for an example: the awkward stumble at 1.18 and the ridiculously brilliant bass drum flams between 2.06 and 2.16 are all part of the same package.) Although instinctively capable of generating rhythms of sometimes startling complexity, the appeal of Keith’s playing goes well beyond “technique,” and it’s that something beyond that I’m striving to catch at, here. What he lacked in technique, he made up for in style.

7. The stop-start structure of the song means that these rapid thumps leap out of silence and onto the ear like an insistent but irregular heartbeat; Keith’s bass drum pumps “My Generation” with an aggressive vigor that both mirrors and counterpoints the quality of adolescent confusion conveyed by the stuttered vocal. Again, this represents a boldly original utilization of part of the kit that is more often relegated to the elementary metronomic function of marking the first and third beat in a conventional four-four time signature.

8. Townshend says somewhere — perhaps on the DVD extras that accompany the most recent release of this concert — that he was a bit worried before the show about Keith’s condition, although I’m presently unable to locate the exact source.

9. James Wood, The Fun Stuff and Other Essays (Picador, 2012), 6. I’d written most of this essay before discovering Wood’s piece, or else I would probably have cited it more often; as it is I recommend it, along with Tony Fletcher’s book, to any serious enthusiast of Moon’s work.