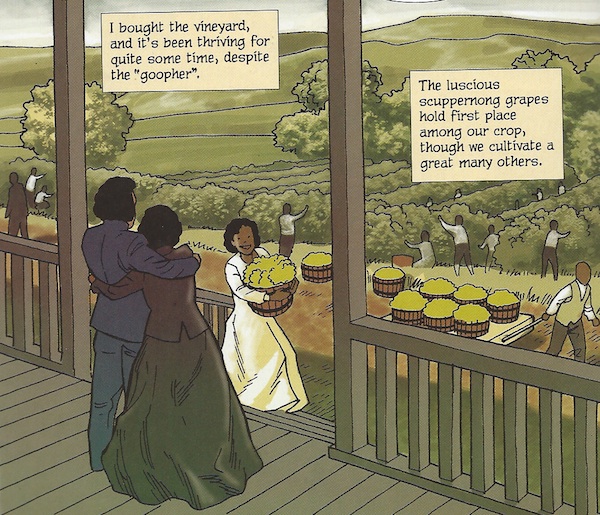

John Jennings seems like he’s got superpowers himself, he’s involved in so many projects. He teaches at the University of Buffalo. He’s involved as a curator of the Black Comix Arts Festival. He collaborates with Stacey Robinson on the Black Kirby Project; he’s just co-edited a new book about black identity in comics called The Blacker the Ink, and he’s got about a bazillion other comics projects he’s working on.

And as if that’s enough, he took time out to talk to me about black superheroes, Jack Kirby, Blade, Power Man, and Captain America’s black sidekick (not that one). Our conversation is below—part of HU’s ongoing roundtable on the question of Can There Be a Black Superhero?

______

‘Night Boy’ created by ‘Black Kirby’ (John Jennings and Stacey Robinson) and Damian (Tan Lee) Duffy

Noah: What do you like about Kirby, and what are you less fond of?

John: I think it’s more liking than disliking. I remember being a kid and not being attracted to the work and all. I felt like he was destroying the characters that I love so much. Because, his work on Captain America, as a kid, it looked blocky and crazy looking and abstract. But for some reason you notice the work and you’re attracted to. And as I got older I started to realize, this guy was actually creating some of the conventions, as far as how superhero comics are done.

And then when we started working on the Black Kirby project, we started to realize how experimental it was. I remember reading this interview about the Black Panther. And he said he felt like his friends who were black should have a black superhero. And he did create a character who was African and not African-American. Instead of creating a black character that would be from his own country. And also the fact that Wakanda doesn’t actually exist.

I thought Don McGregor’s run on Black Panther was in some ways really progressive, and then we turn back to Kirby and it becomes this weird cosmic odyssey thing with this monocole dwarf guy. It’s really strange. It’s this odd thing to happen after a story grounded in progressive ideals. Because McGregor had him fighting the Klan, and he was in Africa helping out his people, which was great. But I think Don McGregor as a writer has always been a lot more connected to the ideas of the black subject.

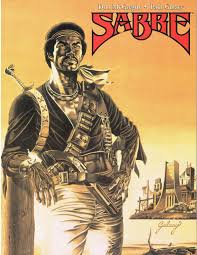

If you look at something like Sabre. Sabre was centered in a post-Apocalyptic world, and the main character was an African-American man. And he was in an interracial relationship with a beautiful white woman. Most of it was about him trying to protect his family. It’s interesting because the character —he looked like he was loosely based on Jimi Hendrix. He was very swash-buckling, always musket and sword in hand. Had this pirate feel to it. It was a funky book, and this was Don McGregor.

Paul Gulacy and Don McGregor

Yeah, I’ve been trying to read his Power Man. Which, I feel like he’s much more conscious of racial issues. He has a hooded Klan like supervillain attacking a black family who’s trying to move into the suburbs. The writing’s just hard to get through. It’s not written very well.

Right—as far as—that era. If you reread the Essential Power Man, it’s bad.

It’s overwitten and it doesn’t make any sense and the dialogue’s a mess.

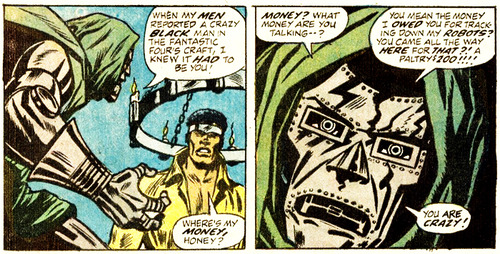

Have you seen Jonathan Gayles documentary White Script, Black Supermen? Gayles is a cultural anthropologist. The impetus for him creating the documentary was this one story where Luke Cage tries to get $200 from Doctor Doom. And he was totally disgusted by the fact that this guy was just a hustler. And that was part of the dissonance. You have a black reader, and this is the first African superhero to have his own book. He is also an ex-con. And he is not necessarily really a superhero, he’s a mercenary. And he’s working in the hood primarily, adn his villains aren’t really well thought out.

Steve Engelhart and George Tuska

They didn’t really understand what they were talking about with that particular character.

Race in superhero comics was really strangely handled early on. Because it was directly related to blaxploitation films. Superhero comics are very reactive and they are a business and they see trends and they try to jump on top of them. And that’s pretty much what happened. That’s where you get characters like Shang-Chi, who was pretty much Bruce Lee.

So, I’m wondering, given the inauspicious start with black superheroes, why are black superheroes important. Or why do you still care about them?

It’s interesting, because the superhero as a structure, it’s an old idea. From the 1930s. I think it’s important for people who participate in society to see themselves as a hero of some kind, or to see themselves in a space where they feel that they can connect with popular culture.

Because popular culture is our culture. That’s a lot of times the first time you see or recognize yourself is through the popular media you watch. I know it affected me as a kid coming up, watching pulp fantasy stuff and reading these things.

And honestly there’s a lot of serious issues with superheroes as a genre. It’s hyper-violent, it’s misogynist, it’s just very sexist, it’s kind of homophobic. But it’s ours; it’s our thing. It’s an American construction. And I understand why it exists—and it does mean something when you’re not there. I think that’s the thing; there needs to be representation, as far as a diverse array of representations. And written from the right standpoint as well.

And honestly I think it’s more important to have black creators working than it is to have black superheroes. Because there’s a handful of black writers in the mainstream. One of the most important books —I don’t know if it’s going to get canceled, but the new Ghost Rider book. A Latino character, a Latino superhero, written and drawn by two African-American men. That was unprecedented; I don’t think people really knew that that was happening. And it’s Marvel.

I think there’s something about just how dominant the superhero is right now. As I think it really is as popular as it was in the 30s. It’s just not in the comics.

One of the thing that bothers me, is that people say what kicked off the trend was the X-Men movies. But it was in actuality the Blade film. It was 1999, and that predates the X-Men movie.

How was the Blade film? I haven’t seen that.

Blade is awesome. You know why I like Blade? Because it’s a Blaxploitation movie with vampies.

That sounds pretty good!

It’s a fun movie. I don’t know how much of this is legend and how much is truth, but Wesley Snipes, he wanted to be Black Panther. But they wouldn’t let him do Black Panther, so he was like, what else do you got?

So they gave him a C-level character. No one knew who Blade was. I knew who Blade was because I used to read the reprints, but he was kind of a lame character. He had these green goggles, it was a dumb character.

But he translates really well to the screen. THe’s pretty much a martial artist, and Wesley Snipes is an amazing martial artist, he’s a 5th-degree blackbelt. So he choreographed the entire movie. It looks great. It’s out of control crazy.

My friend Sundiata Cha Jua, a historian, says that after Blade was successful, Marvel began to take over the franchise. When you watch the first film, it’s a very “black” movie. He relies on this serum to prevent him from becoming fully a vampire, he’s a daywalker. And if you look at the first movie, he gets his serum from this Afrocentric incense store. And he’s in a community of black people and they know who he is. And I thought that was really important.

But when it starts making more money—because Blade made a lot of money. They start to dilute his connection to the black community. And they start erasing him from his own movies. And as I recall, I think Wesley Snipes took them to court over the third movie. Because he’s barely in it. It’s Ryan Reynolds and Jessica Biel because they were trying to create a spin-off to Midnight Suns or something like that.

Or you look at Stan Lee’s movie, his documentary, which I enjoyed. But again they don’t mention Blade as the jump off for the Marvel scene. Or for the Marvel franchise. Stan Lee did not create Blade. Gene Colan and Marv Wolfman created Blade. So it doesn’t make sense for him to be in Stan Lee’s movie. But it’s false to say that the X-Men jumped off this franchise.

I saw a couple of articles, like, hey, don’t forget about the Blade movie.

Is part of the problem with getting more black characters and more black creators is that the superheroes are so centralized in Marvel and DC? There’s so much energy and interest in the big two, that the only way to get a black superhero is to make Captain America black, or something like that.

I have to back up a little. I’m interested in the mainstream characters. As an exercise, I think Black Kirby works because it’s making fun of the superhero genre, and bringing in black power politics. It’s celebrating Kirby but also critiquing him. And it’s interesting as a visual exercise, or as a critical design project. But honestly I don’t have that much interest in mainstream superhero comics as far as black expression. I’m really not satisfied with what I’ve been seeing.

Or the characters who I really like, they screw them up or they do something wrong with them. Like, Mr. Terrific, I love Mr. Terrific, but his book was awful. I think the more interesting things around diversity are happening in the independent black comics scene.

Because it’s not just superheroes. It’s all these different types of genres; there’s action adventure, like Blackjack. There’s stuff like Rigamo, which is magical realism gothic fantasy.

Che Grayson and Sharon De La Cruz

So with mainstream comics there’s issues around nostalgia. Nostalgia is a very powerful thing. So not only do they want to be accepted by the mainstream, but they want to make a monthly comic book. It’s very difficult to do that when you’re flipping burgers or you’re teaching a class here or there trying to make ends meet. It’s a very differnt model. I want to tell them, no, make books about your expeirence, and put them out when you can, because you’re not DC.

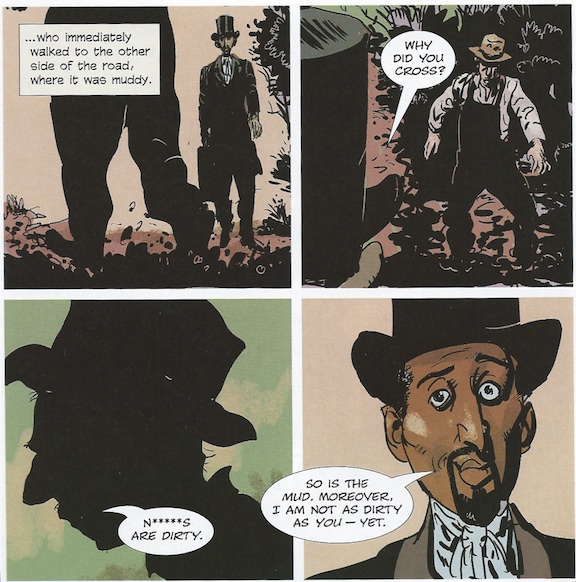

It seems like there’s a problem with nostalgia and superheroes for black people, since black experience in the past was often one of oppression.

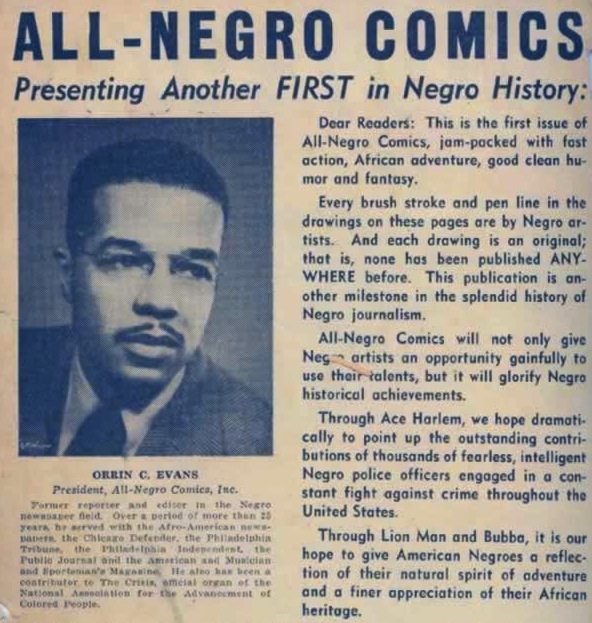

The 1930s when the superhero were created, the first black characters were extremely racist. You had characters like Whitewash who was Captain America’s sidekick, and his superpower was that he always got captured and had to get rescued. He was in blackface and he had on a zoot suit.

Whitewash Jones was created by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby. His dialogue was often written by Stan Lee

And of course guys like Ebony White from the spirit. They’re based off how the black image had been constructed in minstrelsy and other racist propaganda. Even advertisements and products that were being generated had these extremely derogatory, hyperbolic stereotypes. So illustrators when they draw the pantomime of a black image, they’re drawing from the Jazz Singer directly.

I’m curious about what you think about the fact that one of the things for the superheroes is it’s about law and order.

I think it’s about justice. That’s the thing—my favorite superhero is Daredevil. I totally related to this kid. Because I was bullied, and i was poor, and I thought I was smart—I was pretty smart. I just related to that character, and he was a fighter, and I liked that about the character. More than anything, I just loved the fact that he was too stupid to quit. I loved that. That’s his real superpower, and that’s an interesting life lesson to pick up. Don’t give up. I’ve seen many stories where Daredeivl would have died if he just gave up. But he couldn’t because his father taught him not to. I thought that was awesome.

Yeah there’s this thing about law and order, but they’re vigilantes, and they’re saying, in this resounding voice, I have the power to make things right. A lot of people were really upset when they saw Captain America punching Hitler in the face back in the day. They’re violent characters. And they’re reifications of a particular type of jingoistic urge. But they’re ours and they love them.

I love superheroes. And I hate superheroes at the same time.

I think that most folks who don’t understand how these problems in our society actually manifest think that if I do this “one thing” then the problem is fixed. It’s a very Western way of thinking. We are taught to think about the “object” and not the “system”. So, making one African superhero is awesome but, what about the systemic issues around the disparity in the first place? It’s the same problem with integration in our country historically. Our country would put “minorities” in a white space to prove a point or to illustrate a law. It hardly ever thinks “once they are in this space have we really provided a place where they can grow and flourish”. It needs to have this token example to say ” Yeah. It’s messed up in our country but, look at this ______________. See? We got that issue covered.”

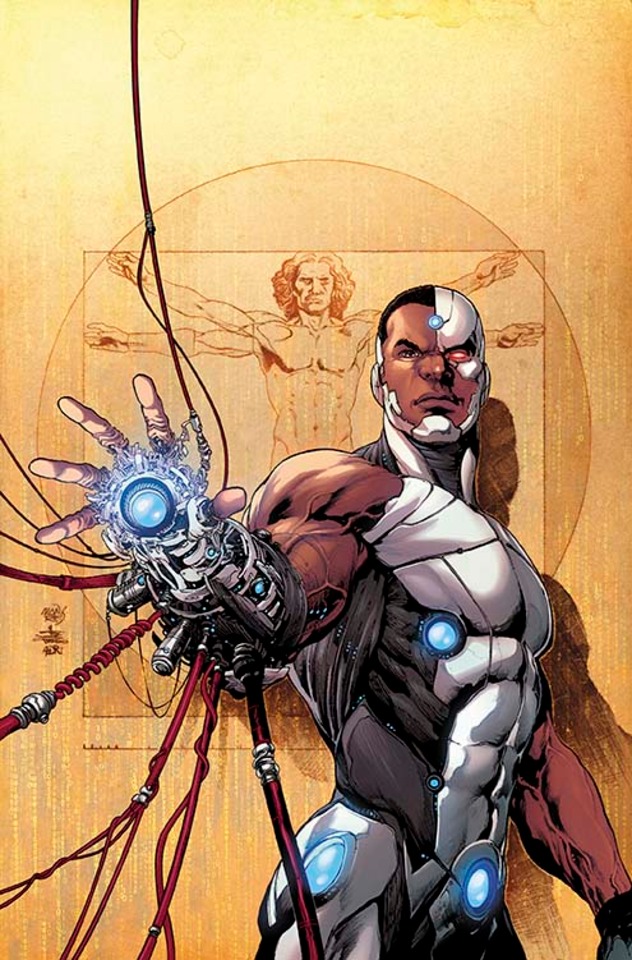

So now. We have a black writer (David Walker) on a black superhero at DC (Cyborg). Let’s see how it pans out. David’s a good friend and great writer. Should be exciting!

Art by Ivan Reis and Joe Prado for the new Cyborg series