This first appeared on The Dissolve.

_______

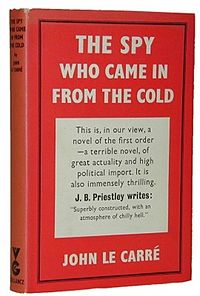

Spy narratives as a genre usually involve über-competent assassins performing death-defying feats in exotic locales with advanced weaponry and smoldering sex appeal. Even supposedly realistic takes like John le Carré’s novel The Spy Who Came In From The Cold present spies as grimly competent soldiers occupying a moral universe that’s glamorous in its grayness. Spies, popular culture insists with almost one voice, are cool.

The spies in Bethlehem aren’t cool, they’re a combination of bureaucrats and thugs. Razi (Tsahi Halevi), an Israeli intelligence officer dealing with Palestinian terrorist threats, doesn’t have neat gadgets or exciting missions like James Bond. He just has a list of contacts he pumps for information, using a combination of bribery and bullying. One of those contacts is a teenager named Sanfur (Shadi Mar’i), whom Razi recruited by threatening his father when the boy was 15. Razi doesn’t have cleverness or martial-arts skills. Instead, he has a shameless, amoral willingness to take advantage of those with less power. In fact, to the extent that Razi attempts to protect Sanfur and treat him as a human child rather than as a thing, he ceases to be good at his job.

Sanfur, for his part, is effectively a spy as well. He passes information to Razi, and he also secretly works to funnel money from Hamas to his brother, resistance fighter Abu Ibrahim (Tarek Copti). Though in some sense he’s Razi’s double agent, that doesn’t indicate any particular competence on his part—just confusion and divided loyalties. He’s a kid who loves his brother and wants his dad and friends to admire him, but he’s also an undercover agent. The contradictions are insupportable; everything starts to fall apart when Sanfur is injured after daring a friend to shoot him while he’s wearing a bulletproof vest. He’s living a life of incredible risk, danger, and deception, but he needs to prove his manliness through idiotic swagger.

He isn’t alone, either. The Palestinian resistance is presented less as an organized battle against the oppressor, and more as a fragmented, endless pissing match—in one emblematic scene, two rival factions almost shoot each other over which of them gets to bury a martyr. In another sequence, rebel leader Badawi (Hitham Omari) challenges a rival to run up several flights of stairs in boyish horseplay, then, when the guy is exhausted, cold-bloodedly pushes him over a railing. There’s no heroism here, just petty betrayal and banal violence. That goes for the Israelis as well. The one big blow-out fight scene occurs in some poor Palestinian family’s home, after Ibrahim flees there. Razi saves the day not with derring-do, but by discovering that the wife has cancer, and using that to blackmail her for the floor plan.

“There’s nothing I hate more than dishonesty,” Razi’s spymaster boss Levy (Yossi Eini) tells him. The irony is that it’s Razi’s job to lie; that’s what spies do. But the further irony is that the boss is right; dishonesty is unforgivable. But in a police state like Palestine, it’s also inescapable, corroding everything it touches: relationships between brother and brother, between neighbors, between friends. In a spy story, Bethlehem insists, there are no good guys or bad guys, and no victor—just day-in, day-out deceit and betrayal, the weary work of hate.