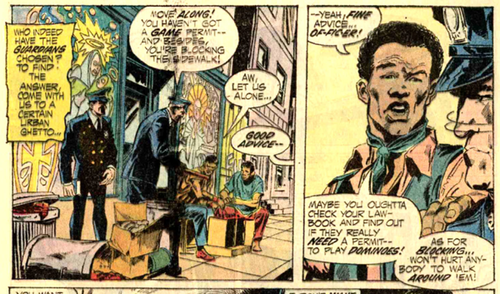

John Stewart’s first appearance in comics, in 1972, involves him challenging a police officer. Some blond cop is harassing two guys playing dominoes on the street, and Stewart tells the pig to back off. “You want trouble,” the cop sneers, and Stewart replies, “I kind of doubt you’re man enough to give it—even with your night stick!” The cop is about to do something more…when another cop comes up and tells him to back off. “Fred, respect has to be earned. The way you acted, you don’t deserve a nickel’s worth!” End of parable.

That parable strains credulity even more than a magic wishing ring—and perhaps for that reason, it needs to be retold, on a broader scale. Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams want to talk about racism—but they need to do it without in any way implicating systems. Racism is caused by bad people like Fred the cop, who fail to act respectfully. It is thwarted by individual bravery (a la Stewart) and by the forces of law and order themselves (like that second cop.) The forces of authority and justice, the folks with the uniforms, are the good guys. Doubt them not.

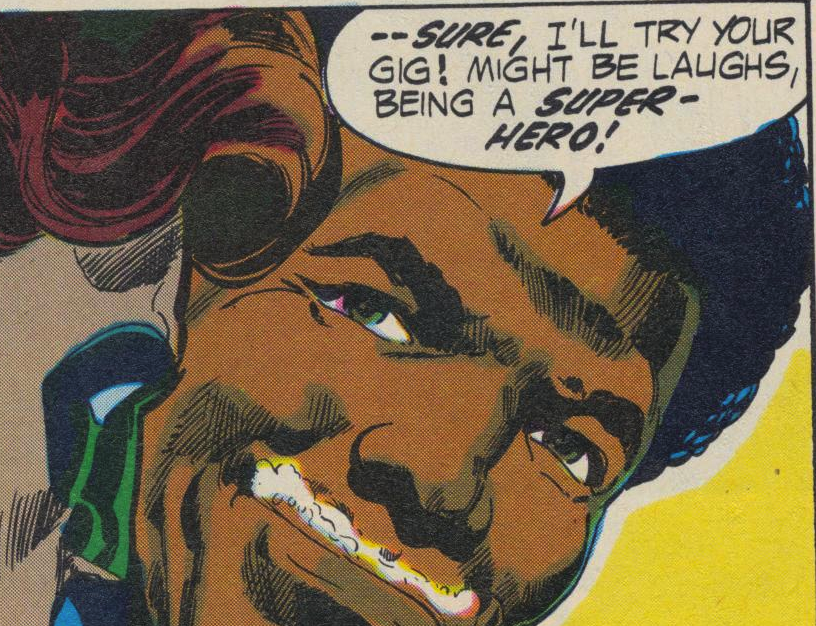

And so the plot grinds on. John Stewart learns he’s to be the back-up Green Lantern to Hal Jordan, and, in the space of a page, he goes from defying cops to being a super-cop himself.

A new bad apple authority figure is quickly introduced in the person of a racist Senator. Stewart (like that bad cop) disrespects the Senator, and is punished by good cop Jordan, who insists that Stewart become the Senator’s super-bodyguard. Stewart is also reprimanded for calling Jordan “whitey”. “Something in that reminds me of that bit about “he who is without sin casting the first stone” Jordan huffs testily. On the next page, Jordan says that the Senator’s racist diatribes are protected by free speech. Mild epithets against white people are anathema; but the black guy has to be told that the Constitution ensures politician’s ability to encourage actual racist violence.

A black person tries to assassinate the Senator, and Stewart refuses to stop him, which pisses Jordan off. But then it turns out Stewart had deduced that the assassination plot was a false flag operation; the shooter was meant to miss, and then another shooter was going to shoot someone else, and the Senator would use the ensuing chaos to bring about race war. Jordan admits that he was put off by Stewart’s “style” but he now recognizes that the back up Green Lantern is a good egg. “Style isn’t important any more than color!” Stewart says, couching the lesson in terms which carefully dance around the possibility that whitey Jordan’s initial prejudice against Stewart might have something to do with race.

Not coincidentally, the plot here precisely mirrors that of X-Men: Future Past. In that film, the heroes must save the establishment officials who threaten them in order to prevent a backlash in the form of a race war. And so too John Stewart has to act to prevent a guard being shot in order to prevent the racist Senator from starting a second “Civil War.” In both cases, the stories are about marginalized heroes threatened by the establishment. And yet, the plot tergiversates about in order to allow those superheroes to do what superheroes always do — protect the status quo.

And what happens to the Senator himself? He is implicated in attempted murder, but the heroes don’t even bother to arrest him. “I’m certain your colleagues in Congress will bounce you back where you belong!” Jordan declares. Stewart, who you’d think would have to be somewhat skeptical, tacitly endorses this naive and surely extra-legal approach to criminal accountability. But ensuring equality before the law is less important than assuring the reader that the people in power aren’t all bad, whether they be police, congresspeople, or the white Green Lantern. There can be a black superhero, it seems—as long as his main focus is saving white people’s self-image, and not black lives.