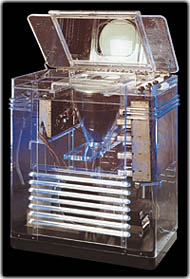

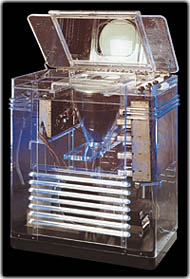

John Vassos is best known among mid-century scholars like me for designing the RCA Phantom – the see-through lucite television set on display at the 1939 New York World’s Fair that convinced skeptical visitors that, indeed, the pictures on the television were generated from within the machine.

A more opaque version eventually became the first mass produced TV set.

He’s also known as a defender of the streamlined Art Deco aesthetic: according to his 1959 correspondence with furniture-maker Hollis Baker, he removed the fins from his mid-‘50s Cadillac in protest of the “more is better” populuxe taste of the post-war decade and as early as 1938, he criticized Hollywood’s subtle semiotic derogation of modern design – they gave nice girls Colonial homes, while less virtuous women lived in Deco flats.

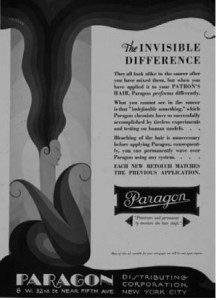

In Hollywood’s defense, there is something sensual and decadent about Deco. Although the eroticism was more overt in Art Nouveau, French Deco in particular tried to reimagine the same themes in a mode more comfortable for bourgeois sensibilities. In the United States, in the 1920s, as the modern consumer economy was forming, Deco was taken up by designers, like Vassos, who were working in advertising and industrial design and who believed that Deco’s “modern aesthetics” would elevate ordinary objects. From this, Deco became America’s iconic aesthetic of bourgeois luxury.

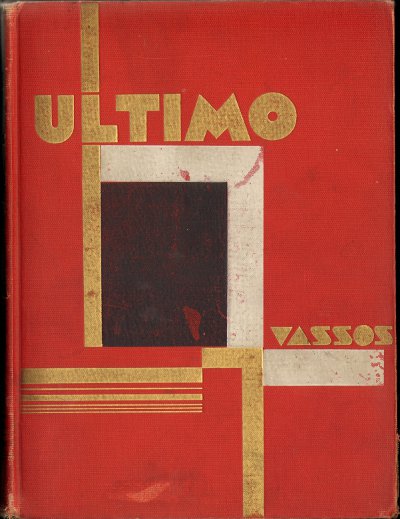

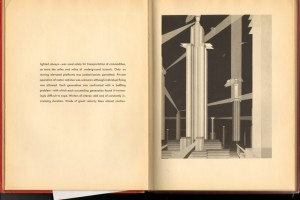

Mostly prior to going to work at RCA in 1933, Vassos illustrated a number of books – several by Oscar Wilde, some Thomas Grey – but he also created illustrated books on his own and in close collaboration with his wife, the writer Ruth Vassos. Most scholarly discussions of the Vassos’ books have focused on 1929’s Contempo: This American Tempo and Ultimo: An Imaginative Narrative of Life Under the Earth, released in 1930. Both books confront head-on the dehumanizing effects of the machine age, and deviate from much Deco advertising and design in that their representations of people are less stylized and impersonal, more like the sensual figures of Art Nouveau. This ambivalence about Deco’s modernity and that modernity’s dehumanizing edge is perfectly embodied by Vassos’ plates.

[Click here for an example of several plates from Contempo.]

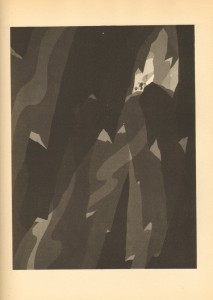

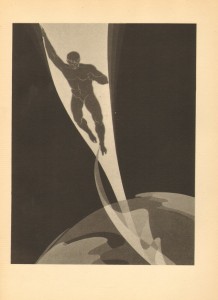

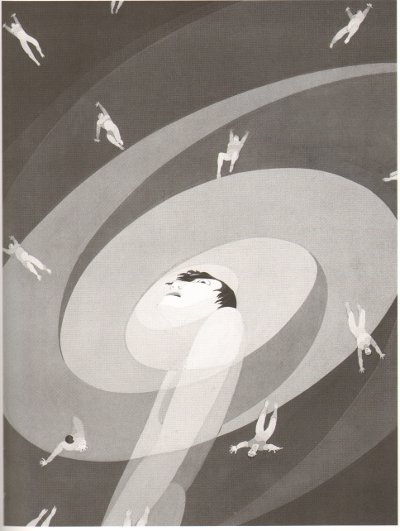

1931’s Phobia continues this theme of dehumanization but with psychology’s inward-looking focus. The volume contains 23 plates illustrating various psychological phobias, preceded by descriptive/explanatory text that is often poetic but of inconsistent quality. Vassos explains in the introduction:

A phobia is essentially graphic. The victim creates in his mind a realistic picture of what he fears, a mental image of a physical thing. The sufferer from acrophobia, for example, sees his body hurtling through space, the aichmophobiac projects an image of himself in the act of stabbing; in this mental picture the thing that he fears becomes actual, for all that its projection is purely imaginative. It is this mental picture that I have endeavored to set down – the imaginal, graphic annihilation that the phobiac experiences each time his fear is awakened…they are intended to be inclusive – that is, to depict both worlds of the phobiac’s existence: the physical and the imaginary, the actual and the projected. The real world is replaced by the unreal as the pictorial pattern of the sufferer’s destiny parades ceaselessly through his mind.

Although influenced by the psychologist Henry Stack Sullivan, Vassos’s particular understanding of phobia’s graphic anchor appears to be his own. (Sullivan scholars can correct me!) But it remarkably prefigures the post-Freudian/Lacanian understanding both of the role of images in psychology as well as the abnegation and de-centering of the psychological subject.

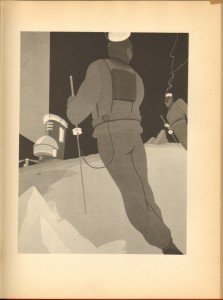

When combined with the dehumanizing effect of industrialization, these themes become particularly palpable in the panel for Mechanophobia, which juxtaposes the fear of machines with the Machine Age’s emblematic aesthetic.

This connection of pre-war visuals with the psychology of the post-war era, when futurism and Deco had been left behind due to their associations with fascist propaganda, creates an aesthetic time-shift worthy of Philip K. Dick. It’s one of those rare and immensely satisfying moments where a postmodern ethos leaps out fully formed from a Modern work supposedly created decades before postmodern was first thought. But there are also visual displacements – can they be allusions if the referent hasn’t happened yet? – referencing the art of the 1960s, particularly in the lower left quadrant. These only further the disorienting out-of-time effect of the panel.

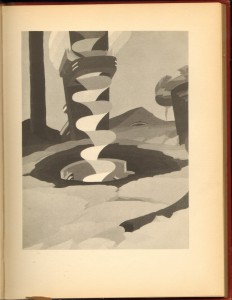

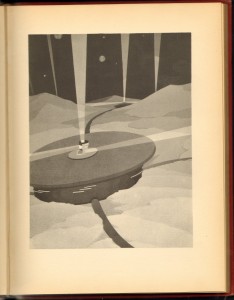

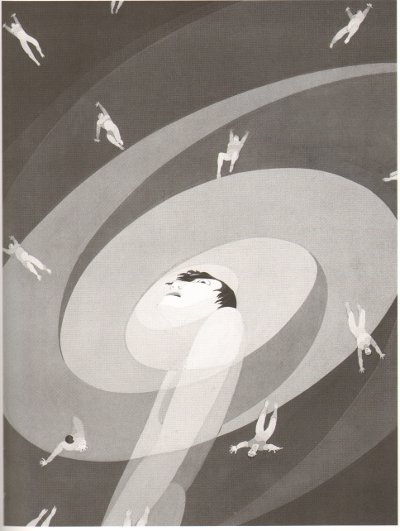

Similarly, the use of a vortex

to depict the generalized pantophobia (fear of everything) is also reminiscent of mid-century design to a present-day viewer. Saul Bass put the swirling imagery to the same purpose in the credits to Hitchcock’s Vertigo and psychedelic art used it to represent the disorientation and sometimes-paranoia of drug experience. It’s hard to tell whether the images are so culturally prevalent because they really do resonate psychologically at some unconscious level, or whether they’re simply so culturally pervasive that we unconsciously grab onto them to depict these experiences.

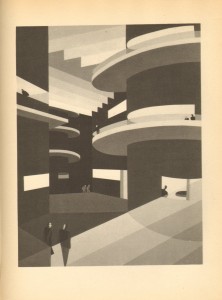

Of course, there are plenty of panels that are just palpably from the 1920s: Climacophobia (fear of falling down stairs) is particularly so.

But nonetheless there is in this volume an overwhelming sense of having encapsulated something vital about the 20th century before it actually happened. The argument can be made that America’s 20th century was dominated with the struggle between the needs of industrialization and the needs of the psyche. Vassos’ brilliant work embodies the tension between the two.