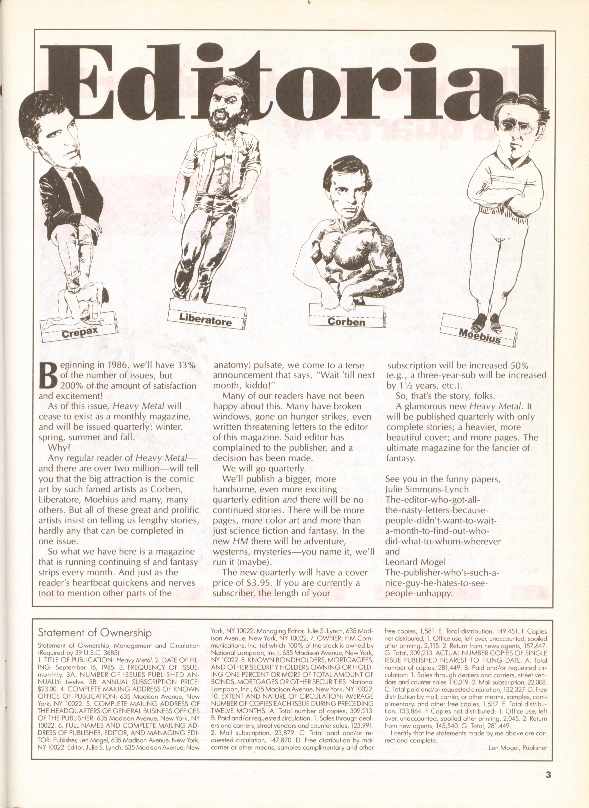

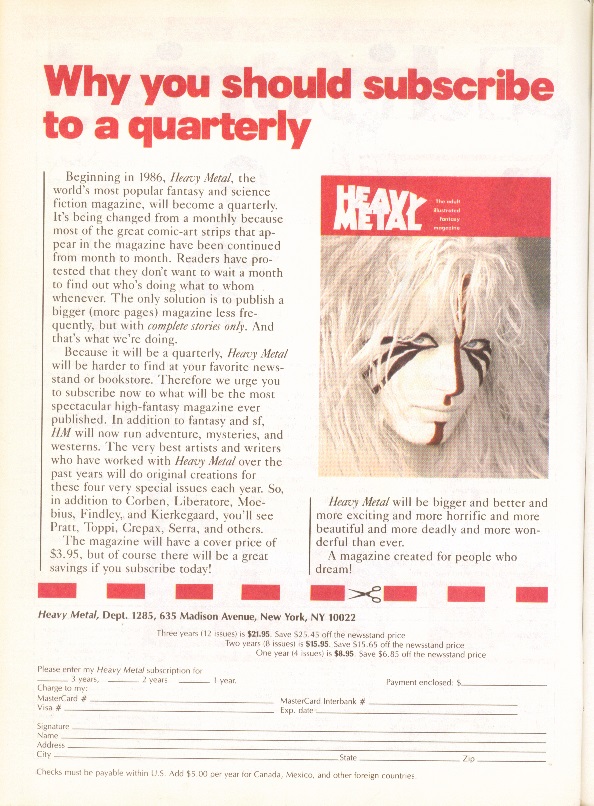

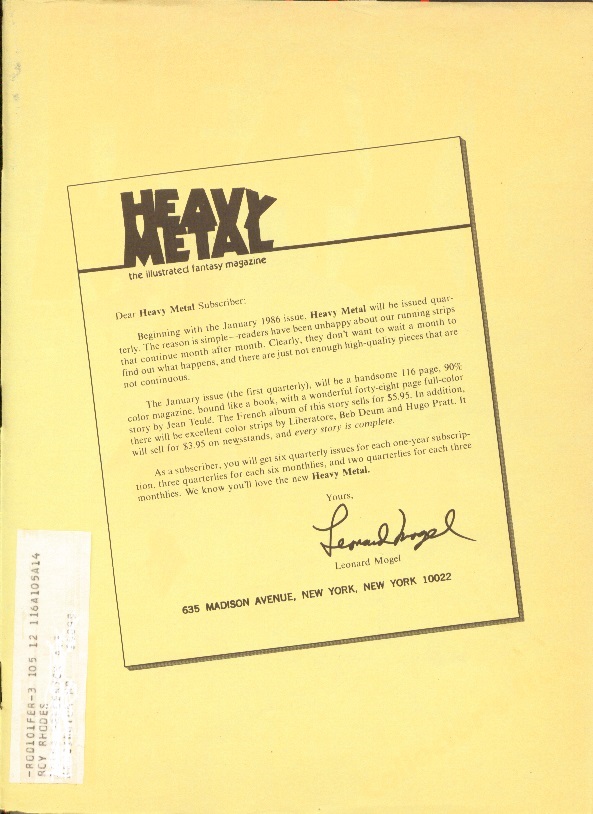

When subscribers received their copy of the December 1985 Heavy Metal in the mail, they were greeted with a letter from publisher Leonard Mogel, printed on the paper mailing wrapper, informing them that with the next issue, Heavy Metal would be moving from a monthly publication schedule to a quarterly schedule. The reason provided was simple: readers were unhappy with the fact that the stories in the monthly version of Heavy Metal continued from one month to another. Quarterly publication allowed the magazine to increase the page count from 96 to 116 pages, add perfect binding and to publish complete stories in each issue. Oh, and the cover price went from $2.50 to $3.95 (the equivalent of jumping from $5.40 to $8.53, adjusting for inflation).

Having read every issue of Heavy Metal through 1986, I’m not entirely convinced that “the audience wants complete stories” was the whole reason for the shift in publication frequency. Looking at the individual magazines that were published in the years before the shift, it’s easy to spot how a combination of cost-cutting measures and behind-the-scenes change in staff might have also contributed. Having said that, “readers want complete stories” was convenient and easy to explain and a lot more audience-friendly than “we’ve had some staff issues.”

And boy, did they have staff issues in 1984 and 1985. But in order to explain the full impact of those staff issues, we have to go all the way back to the January 1978 issue of Heavy Metal, when John Workman became the magazine’s second Art Director. In that January issue, Workman was co-credited as Art Director with Harry Blumfield, who had been working in the position since the first issue. In February, Blumfield was gone and Workman was in.

Workman’s influence was not obvious at first, but over the course of the next two years, he built up the quality of the production. When editors Sean Kelly and Valerie Marchant were replaced by Ted White in 1980, Workman survived the transition. He also survived when Ted White left at the end of 1980 and was arguably one of the mainstays holding the staff together during the transition. Throughout this period, Workman’s name lingered near the middle of the credits on the masthead, never getting higher than fourth. This is significant, because I believe where the individual ranked on the masthead was indicative of where they fit into the staff hierarchy; whether or not this is true, it seems clear that members of the staff at the time believed it to be true.

In fact, Leonard Mogel’s name appears at the top of the masthead throughout most of 1981, reflecting a more active involvement in the day-to-day activities at the time. Julie Simmons-Lynch is credited as the editor, but it was obvious that she didn’t have the same kind of hands-on relationship with the production as Kelly/Marchant or White. They needed someone to pitch in and take care of operations.

Accordingly, in the March 1981 issue, a new name appeared on the masthead – Brad Balfour, Contributing Editor. His editorial efforts were largely forgettable, but Balfour was a terrible interviewer and badly botched an interview with Richard Corben which ran in June, July and August of that year. This series precipitated an angry full-page letter from Corben, who demanded that the letter be printed in full, with no edits. This letter appeared in the September 1981 issue, the same issue that was dedicated to the Heavy Metal movie that was released on August 7th of that year. It was not the best use of editorial synergy and was largely reflective of the state of the magazine in 1981.

In addition to the movie, which brought in hordes of new readers, the other major event of 1981 was the release of an entire special issue, dedicated entirely to Moebius. This Moebius special featured (among other things) an introduction by Federico Fellini and the first few chapters of The Incal, a serial written by Alejandro Jodorowsky and drawn by Moebius. Workman and his team did a lot of the heavy lifting for this issue and Workman was given top billing in the masthead. Perhaps coincidentally, Mogel’s name was no longer on the masthead for the December 1981 issue of Heavy Metal and Workman’s name was second, right underneath Simmons-Lynch and above Contributing Editor Balfour. Workman’s name remained in this position on the masthead until he left in 1984.

Workman’s contribution to the magazine was everywhere and, thus, only truly obvious after he left. He contributed a lot to the look and feel of the individual issues, producing spot-art and the occasional one-page story when it was necessary to fill a gap. Although he was never credited as an editor, he was the Art Director in a publication dedicated to art and the magazine was better off having an Art Director in such a prominent role in the leadership.

The February 1982 masthead had some major changes. In addition to Brad Balfour becoming an Associate Editor, there were some new names, most notably Lou Stathis as Contributing Editor and Steven Maloff as Editorial Assistant. Since October 1981, Stathis had been working on Dossier – the spiritual heir to the columns that White had added when he was the editor in 1980. In this incarnation, Dossier was focused largely on music, with healthy digressions on movies, books and video games. There were far more writers than White had in 1980 and the topics bounced all over the place.

February 1982 masthead

Balfour was the first real editor of Dossier, but Stathis took over when he was promoted to Associate Editor in May 1982. As for Balfour, he was credited with “Special Projects” and disappeared from the masthead entirely in October 1982. Maloff was promoted to Contributing Editor in July 1982 and not a lot else changed in Heavy Metal leadership for the next two years.

Dossier November 1983

I would argue that this incarnation of Heavy Metal, with Workman, Stathis and Maloff, was one of the best periods of Heavy Metal, full stop. When Stathis wasn’t busy picking fights on the letters page (sample response: “Yeah, but I’ll bet your dick has to hunt and peck when it types.”), he was turning Dossier into a powerhouse review section that also ran interviews with all kinds of creative types, from Jerry Lewis to Jack Davis and everyone in between.

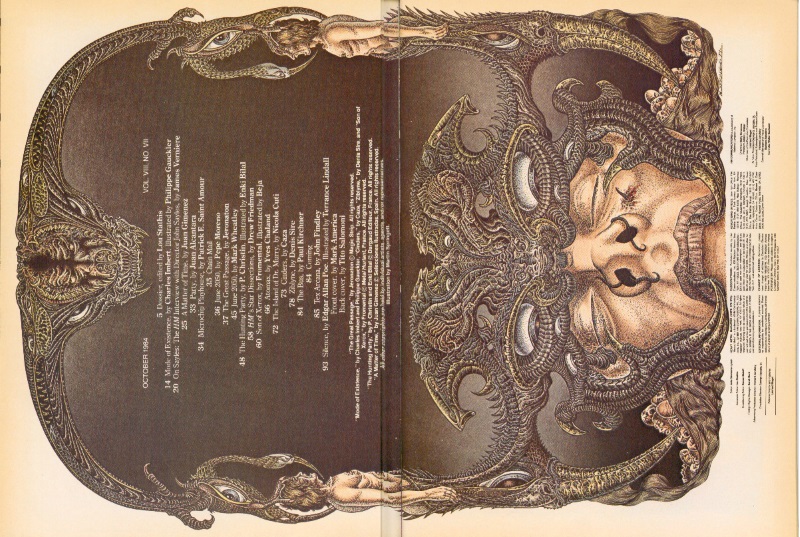

For his part, Workman was busy turning Heavy Metal’s visual content into something legendary. In addition to long-running series like Rock Opera by Ron Kierkegaard, The Bus by Paul Kirchner, Tex Arcana by John Findley, and I’m Age by Jeffery Jones, Workman also put together a series called June 2050. This featured one-page vaguely science fictional stories by various comics luminaries including Dick Giordano, Chris Browne, Drew Friedman, Rick Veitch, Bill Dubay, Len Wein, Todd Klein, Rick Geary, Howard Cruse and Pepe Moreno.

It’s not clear where Steven Maloff’s influence can be seen during this period.

In 1982, Heavy Metal released a second special issue, their first Best Of. In 1983, they decided that they had enough material to produce a 13th issue, which was branded Even Heavier Metal. Both of these were masterminded by Workman and it’s interesting to note that neither Stathis or Maloff were credited in Even Heavier Metal (I don’t have Best Of #1) – presumably because there was only comics and art-related material on offer. This changed in 1984, when Son of Heavy Metal was released. Here, Maloff was credited as Associate Editor, the only masthead that shows him with this particular title (he was promoted to Managing Editor in July 1984).

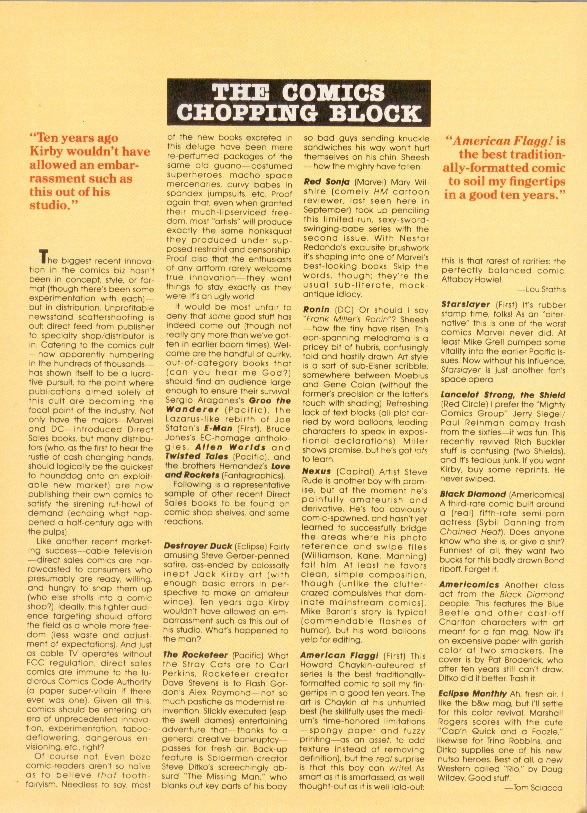

1984 was not a particularly good year for Heavy Metal, production-wise. In January, Bird Dust, a story by Caza was reprinted (a first, for a magazine with so much content that it felt compelled to print 13th issues three years running) – it had originally been printed in the November 1977 issue, two issues before Workman began. In April, the cover price went up to $2.50, the first price hike since February of 1980. The next month, in June, 16 of the 96 pages of the magazine changed from the usual glossy paper to newsprint; this was ameliorated somewhat by printing Dossier and Tex Arcana, a black and white feature, on the lower-quality paper. Coming so close upon the heels of the cover price hike, the lowered paper quality hints strongly at money problems.

And then John Workman left the magazine. The October 1984 issue was clearly laid out by Workman, although his name does not appear in the masthead and neither does his staff. It’s not entirely clear if the departure was planned or unplanned, but there is a clue in the masthead. Steven Maloff, who had been credited as Managing Editor since July 1984, was temporarily demoted back to Contributing Editor in this masthead, which is almost hidden on the credits page. It’s very subtle, but it’s absolutely a message of some kind in Maloff’s direction.

October 1984 editorial

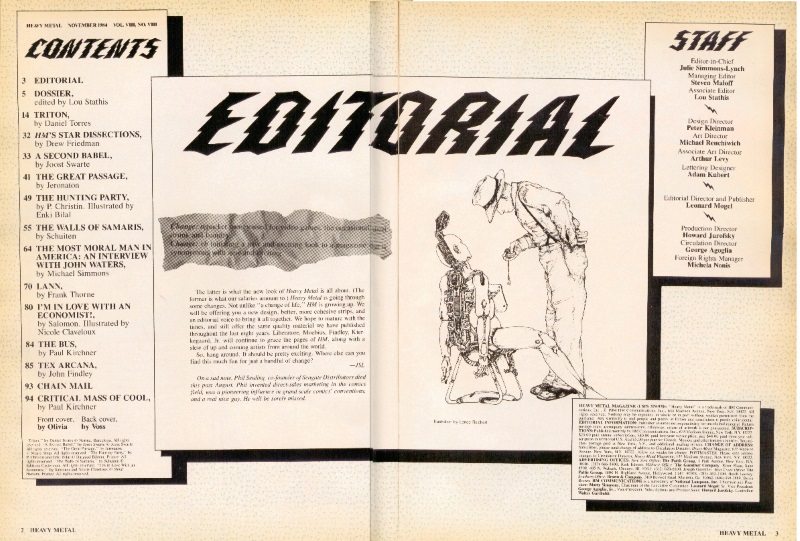

November 1984 editorial

Indeed, the very next month, Maloff’s name was now above Stathis in the masthead, where Workman’s name resided since 1981. There was clearly some kind of power struggle and Workman lost. The magazine was not better off without Workman – the production quality of the magazine dropped significantly in that single month and never really recovered. It was Balfour all over again, only this time they didn’t have a movie bringing in new readers or John Workman providing support.

There is no better indication of how bad things got, production-wise, than the 13th issue from 1985 – Bride of Heavy Metal. Workman was long gone by the time this came out and the little details that Workman put into the special issues he produced are not here. And instead of providing distinct credits, the whole issue was “Compiled by the Staff of Heavy Metal magazine,” which is as vague as it gets.

As bad as 1984 was, 1985 was worse. My copy of the February 1985 issue has a major printing error – the registration lines from the red ink don’t quite line up in one of the signatures, an issue that hadn’t been seen in years. In April, Maloff took over editing Dossier from Stathis. In May, the paper quality dropped again, including four bright white pages that were a step up from newsprint, but a step down from the normal glossy paper and tended to let the art from the other side of the page bleed through. In June, the whole magazine had switched to this new paper stock, replacing both the newsprint and the glossy paper. And, in July, Stathis was completely off the masthead. Maloff was now in charge of the magazine, for better or for worse.

One of the lesser ideas that Maloff introduced in July 1985 was a full page of trivia questions called Trivial Metal. In that issue, the answers were not provided and it was run as a contest – readers were encouraged to send in answers with a chance of winning a sweet satin-like jacket with the Heavy Metal logo printed on the back. The contest aspect of Trivial Metal didn’t last long and, by the next issue, the answers were printed upside down on the same page as the questions. This continued for another issue and, in October, the feature was not there. In November, neither was Maloff.

Trivia June 1985

His position was not filled, exactly. Michela Nonis had been promoted to Production Manager in April 1985 and, absent Maloff, became the default bigwig. It’s difficult to tell if going quarterly was her idea or not, but it was certainly a decision rapidly made. The September 1985 issue has a subscription ad that features a good deal for a three year subscription, which pretty clearly indicates that the staff thought they were going to be publishing a monthly magazine for the foreseeable future. There were no subscription ads in October and, in November, the last installment of Dossier published seven interviews – clearing out the backlog of interviews that they had stocked up over time.

The subscription ads and editorials in the December 1985 issue leaned very heavily on the idea that readers had been clamoring for complete stories in every issue for years and the change in format was completely not a last-minute decision by a staff that had run out of ideas for ways to cut costs. This was clearly propaganda, but propaganda that was easier to promulgate than explaining how they’d lost their star Art Director in a power struggle over whose name got to be on the masthead of the 13th issue a year earlier.

December 1985 editorial

December 1985 subscription

October 1984 subscription

I’m convinced that the loss of John Workman led directly to the transition of Heavy Metal from a monthly magazine to a quarterly magazine. True, each of the new issues contained only complete stories, but that was not necessarily a good thing. In January 1983, at the height of the Workman/Stathis years, the magazine boasted fifteen features, not including Dossier. Five of them were short – half-page or single-page comics, but the range and quality of the material was extensive. The first issue of the new format boasted seven full-length features. One featured short, episodic stories and the other offered novellas that were promised to be stand-alone (ie, no sequels).

In addition, there was a certain frisson that came from reading several serialized comics right on top of one another, anthologies being sort of the entertainment equivalent of eating a multi-layer cake or club sandwich. There were a lot of weird, conflicting flavors, true, but the experience was richer for it. Reading two (or more) serials at the same time over the course of several periodical installments creates an associative memory between the two (or more) stories, an effect that can only be achieved through sequential episodic serialization. Complete, non-sequential stories offer a pale echo of the same experience, but cannot (by definition) offer the experience of following a serial across multiple installments.

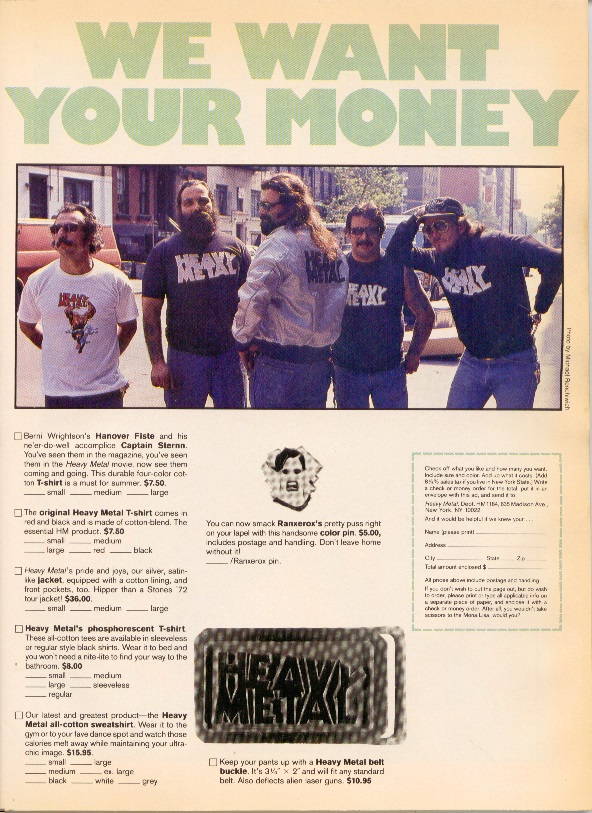

Publishing quarterly didn’t last. After three years, Heavy Metal changed their publication schedule again in 1989, moving to bimonthly and eventually being sold to Kevin Eastman in 1992. In nearly nine years as a monthly magazine, over a third of all Heavy Metal issues to date were published between 1977 and 1985. It was a strong brand that spawned a movie, innumerable branded clothing options and a number of imitators (the so-called ground level anthologies, most notably Epic Illustrated, which coincidentally folded in 1986). It was a mainstay on the magazine rack, month in and month out. Dropping the frequency of publication really limited its visibility in a big way.

In my opinion, the biggest loss was Dossier, which didn’t fit the new format. The Dossier section turned readers on to any number of great bands, songs, albums, movies, authors and other entertainment options they might not have otherwise been exposed to. Dossier had the potential to become a monthly guide to cool, weird stuff for a certain kind of reader with access to a decent record store. Lou Stathis was a contrary proto-goth with a severe aversion to dickheads, but he had great taste in music.

In 1986, as the publication frequency changed, there was an attempt to spin Dossier off into a weekly newsletter called Heavy Metal Report. I can find no information about this spinoff online (and my father, who I inherited my collection from, was clearly not interested because he had no copies). The loss of this review section remade Heavy Metal into more of a pure comics magazine, significantly disconnected from contemporary pop culture.

At SPX, Joe McCulloch reminded me that the stories published in the quarterly years were actually pretty good. A Corto Maltese story by Hugo Pratt, the introduction of Druuna by Eleuteri Serpieri, an old Moebius story and a new Enki Bilal story were all printed in the first year. In fact, one of the few things that survived both the departure of John Workman and the switch from monthly to quarterly was the overall quality of the comics stories. Not every story was a winner, but when they were good, they were very, very good. Moving forward, there were just fewer of them, complete in every issue.