I’m on vacation the rest of this week, so the blog’ll be off the next couple days as well. See you all next week!

Tag Archives: Johnny Cash

Muppet Music

This originally ran on Madeloud a long time back.

__________

There’s nothing quite like a plush floppy critter singing — which of course explains the breakout success of John Denver. It also, to perhaps a lesser extent, accounts for the marvel of musical treasures which was the Muppet Show. Below are some of the highlights.

“Mahna Mahna”

“Mahna Mahna” debuted on Sesame Street in a prototype and then went big time on the Ed Sullivan show in 1969 with the familiar shaggy muppet and the cowlike pink Snowths. “Mah-na Mah-na” (with hyphens) was originally composed by Italian Pierro Umiliani for his Swedesploitation film, Sweden, Heaven or Hell. In the Muppet version, scandalous Scandinavian sex is replaced by scandalous scatting as the irrepressible be-sunglassed beat muppet provokes the Snowths snouts into escalating moues of disapproval. The skit was reprised as the first number on the first episode of the Muppet Show, a version which includes poor Kermit being mahna mahnaed by telephone.

The Mahna Mahna singer does a similar act in “Sax and Violence,” a skit also featuring saxophonist Zoot.

“You’ve Got a Friend”

Vincent Price, in perhaps his scariest role of all time, wears a hideous green jacket, terrifying neckware, and a hairstyle-that-should-not-be to lugubriously desecrate Carole King’s “You’ve Got a Friend.” Henson and company break out a whole murder of endearingly ugly muppets, but, as is his wont, Price emphatically steals the show. His expression of sweetly demented joy at :41 is almost as irresistible as his plodding off-key singing. Indisputably the best version of this song ever recorded.

“I’ve Got You Under My Skin”

This is another performance from the excellent Vincent Prince episode. A giant orange monster and a small frightened muppet duet on Cole Porter’s “I’ve Got You Under My Skin” while the former attempts to eat the later. Perhaps the best thing about the skit is that the violence in the song comes so naturally; you listen and realize, yeah, this…this is a creepy stalker song. “Don’t you know little fool/ you never can win!” the monster declares, and the poor tiny muppet trembles. As well he should, because that’s a really unpleasant way to declare your undying affection to the weird beak-nosed darling of your dreams.

“Orange Blossom Special” and “Jackson”

Johnny Cash does a medley of two of his biggest hits, assisted by Miss Piggy standing in for June Carter Cash. The buck-toothed hayseed muppet puffing like a train is pretty great, but of course the duet is the main thing. Johnny swivels his hips in a unhealthily lascivious manner when the pig makes her appearance resplendent in purple hat and green scarf. She reciprocates by heartlessly drawing attention to his coiffure (“go comb your hair!”) which looks like one of her fellow muppets has crawled up on his scalp and expired.

Cash’s performance of “Ghost Riders in the Sky” with Gonzo as cattle-herder is pretty great too.

“In the Navy”

After a brief selection of soothing flute music from the Peer Gynt Suite, we launch into the Village People classic performed by marauding Viking pigs. The usual Muppet Show protocol is to have the puppet-performed numbers voiced entirely by people who can’t sing. This skit, however is distinguished by being voiced almost entirely by people who can’t sing — there’s one guy there who can actually belt it out. You can hear him at 1:37 — “Can’t you see we need a hand!’ he declaims with some almost professional vibrato while everyone around him stomps forward like they’re in a skit involving marauding Viking pigs and nobody cares whether or not they’re on-key.

“Rockin’ Robin”

Of course, the “nobody can sing” dictum doesn’t apply to house-band the Electric Mayhem in general, or to Janice in particular (here voiced by Richard Hunt.) Though you might miss it behind the goofy interpolations and the cadaverous looking shuffling robin, this tune is actually a strikingly effective arrangement of this Jackson Five classic. The slick Motown R&B delivery system gets changed into a swinging jump blues, with some tasty bass and a soulful drum/gutbucket saxophone interchange. Plus you get to hear Animal yell “Tweet! Tweet! Tweet!”

Janice also sang “With a Little Help From My Friends,”. It’s even sillier…but still manages some musical integrity, I think.

Loretta Lynn

Loretta Lynn’s version of her it-sucks-to-be-a-woman lament is adorned with some of the most disturbing muppets ever created. Giant leering toothy monster muppets are cute…but these human muppet babies with their twisted little apple faces and gaping contorted mouths…eesh. If this were more widely marketed it could single-handedly solve the population crisis.

The baby muppets were featured in a number of other skits as part of Bobby Benson’s Baby Band, always to nightmarish effect.

“The Gambler”

It’s a little hard to believe how thin Kenny Rogers’ voice sounds on this — it was a sad twist of fate which caused him to attain stardom before the Auto-tune. The Gambler needs no vocal enhancement, though; he appears to be simultaneously channeling John Wayne and William Shatner. The old adult-sized human muppets aren’t as viscerally horrifying as Loretta Lynn’s babies, but there is something profoundly wrong about the scene where the Gambler’s spirit steps out of his hand-sewn body and begins spectrally shuffling while his withered seat mates launch into a shaky chorus. The skit is also notable for the muppets’ human hands, and for the fact that what they do with those hands is smoke and drink. You can be Disney isn’t going to let that happen again anytime soon.

“Bohemian Rhapsody”

Over the last couple of years the Muppet Studios have put together a number of viral videos. A split screen “Ode to Joy” featuring multiple Beakers was a major success, as was this everyone-and-their-chickens production of Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody.” Admittedly, for fans of the old show, the relatively slick production values are a little hard to take — and of course with Henson gone many of the voices don’t sound like they should. In addition, the recycling of favorite skits, from “Mahna Mahna” to Beeker meeping seem a little forced. But everything is forgiven for the segment where Animal calls plaintively, “Mama? Mama? Mama mama mama mama mama mama mama!” He’s such a sad and lonely psychopathic beast-creature. Even Freddie Mercury would have shed a tear.

There’s endless more clips worth watching; Beaker fronting the Electric Mayhem on “Feelings”; the epic Animal vs. Buddy Rich drum battle; Joan Baez singing “Will the Circle Be Unbroken” to a family of rats; Marvin Suggs and the Muppaphone; while being manhandled by monsters Alice Cooper performing “School’s Out”. You can surf from skit to skit endlessly on Youtube…or if you want an unbeatable catalog of all things muppet, check out the amazingly thorough Muppet Wiki.

No, You Are Not as Cool As Johnny Cash

This first appeared on Splice Today.

__________

“Some say love is a burning thing/that it makes a fiery ring,” Matthew Houk warbles at the beginning of his latest single, “Song for Zula.” His voice catches and the music surges and shimmers as he earnestly confides, “But I know love as a fading thing/just as fickle as a feather in a stream.”

Houk is, of course, referencing the classic Johnny Cash track “Ring of Fire.” That song is a straight ahead, hit-radio ode to the painfulness of passion — performed with Cash’s trademark trundling beat, it delivers its simple message in two minutes and a half, and then gets out. Houk, on the other hand, offers a six-minute tour de force of searingly honest vacillation — a towering work of genius rising up from Cash’s simple blueprint.

Or at least I think that’s what I’m supposed to get out of “Song for Zula”. A less charitable reading might instead see the track as a bloated, shapeless, default-hippie self-mythologizing mess.

In ostentatiously complicating Cash, Houk can perhaps be seen as offering an alternative to Cash’s baritone working-man plain-speaking masculinity. For Cash, love is fire; for Houk, it’s one thing and then another; he is a sensitive new age guy, and his feelings cannot be contained in your three minute song. The end result, though, is not so much to suggest that Houk is deep as to suggest that “sensitive new age guy” is just a euphemism for “narcissistic windbag.” The droning, fourth-drawer Neil Young imitation backing plods on as Houk praises his own sterling, uncontainable romanticism. ” My feet are gold. My heart is white/And we race out on the desert plains all night.” There’s something about a cage, something about how he’s a killer, something about being free and not being free and it’s all transcendent and lyrical. What is more romantic than to see the romantic admit that his romantic heart is afraid of romance?

In contrast, Cash’s “Ring of Fire” doesn’t come off as romantic at all. Instead, it’s stolidly hokey. The famous Mexican horn flourish makes it sound less like he’s falling into a ring of fire than like he’s unaccountably wandered into a bullfight. His phrasing, always rugged at the best of times, sounds particularly tongue-tied here. The first word, “Love,” is almost off-key; the repeated, “ring of fire/ring of fire/ring of fire” at the fade is so weirdly clunky it sounds like the record is skipping.

The only part of the Cash record that comes across as even vaguely professional is the backing by the Carter Family sisters — June, Anita, and Helen. Their mountain harmonies are mixed low…but not low enough to erase their incongruity.

That incongruity, though, is actually kind of appropriate. “Ring of Fire” was written by June Carter about the experience of falling in love with Johnny Cash — which, as she said on more than one occasion, was a scary thing to do, what with the massive pill addiction and the out of control rockstar antics.

The lyrics may sound simple, then, but the circumstances give them a complicated, and even perverse, double meaning. Cash is singing a song about falling in love with himself; he’s ventriloquizing his soon-to-be-wife talking about him, even as that soon to be wife sings in the background a song that, for most listeners, reads as being about Johnny Cash falling in love with her. Identity and gender stumble clumsily against each other, and/or melt seamlessly into one another — love is, in several senses, not being able to tell the difference. “The taste of love is sweet,” Cash intones, but whose love? Which love? Part of the sweetness, perhaps, is that awkwardness — the simple rush of falling down, down, down, and not being sure who is falling towards who.

In “Song for Zula”, on the other hand, there isn’t really any other who to stumble against. Maybe that’s why the Youtube promo image for the song shows some random woman with her face blurred out and her breasts almost spilling out of her jacket sitting on a hotel bed while another women with her face obscured lies beside her and some ill-shaven alterna-bro laughs heartily in the foreground. The would-be expansive, would-be introspective balladeering is, it turns out, just a soundtrack for banal soft-core. For Houk, the problem with “Ring of Fire” is not so much the metaphor as the topic. Sensitive geniuses don’t fall in love, apparently — at least not with other people.

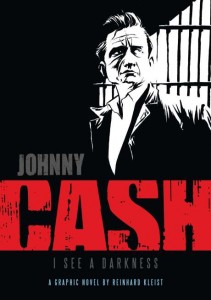

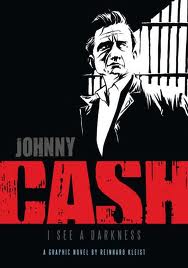

A Review of Reinhard Kleist’s Johnny Cash: I See a Darkness

The index to the Comics and Music roundtable is here.

A version of this review first appeared at The Comics Journal.

_______________________

“A comic for me is something between a book and a movie. It can do all the good things in both media. If it is well done, you can even hear the sound of the music.” – Reinhard Kleist

On the opening pages of Johnny Cash: I See a Darkness, German cartoonist Reinhard Kleist’s English language debut, a young, possibly strung-out Johnny Cash guns down an innocent man, then sits down and smokes a cigarette as the man fades away beside him. It’s a striking interpretation of one of Cash’s most famous lyrics from “Folsom Prison Blues” (“I shot a man in Reno just to watch him die.”) and it sets the tone for the rest of the book.

That tone, of course, is darkness, and as Michel Faber points out in his excellent review in the Guardian, “Kleist’s imagination is fired by darkness.” This is evident not only in the stark black and white images that saturate the book in shadows (Faber refers to it as a “220-page portfolio of inky expressionism”), but even in the choice of a subtitle – Will Oldham’s “I See a Darkness,” a song Cash covered late in his career.

Rather than a straight-forward biography, Kleist’s artistic goal is to capture the emotional experience of Johnny Cash’s music in a visual medium. In an interview with Paul Gravett, Kleist explained that, “I wanted to give the reader a feeling of what I had in mind when I listened to his last albums.” These “last albums” he’s referring to are the legendary American Recordings, Cash’s final six releases (a box set of four additional discs worth of music were also posthumously released) which featured quietly intense covers of some of the most haunting songs ever written, recorded in Cash’s personal studio with producer Rick Rubin. These records were responsible for Cash’s return to the summit of the music industry late in his career, and for introducing the country music legend to a whole new generation of music fans.

Rather than “make music visible in a comic book,” what Kleist actually accomplishes is adapting the underlying stories in some of Cash’s most famous songs into mini narratives. Thus, interspersed throughout are cartoonish episodes featuring Cash, a dashing young comic book hero, seeking revenge against his long-lost father for naming him Sue, or foolishly getting himself killed for “taking his guns to town” despite his mother’s pleas. These mini-strips work fine in terms of illustrating the underlying stories of each song’s lyrics, and do a nice job of breaking the book up into sections, providing an overall sense of structure, but they lack any kind of noticeable pacing, panel rhythm, or other formal technique that actually conveys the sensation of music in the silent medium of comics.

But Kleist is not an experimenter. The action is largely confined to traditional panels and the page layouts rarely venture outside of familiar grid structures. Kleist himself admits that “I’m not a big comic expert! When I am thinking of a storyline or a scene, my first thoughts are like movie scenes and then I try to translate them in the form of comics by using things like camera movements or cuts and so on. That is why my books often have a more cinematic approach and don’t play so much with the possibilities of comics like other comic artists do, like Art Spiegelman for example.”

What makes Cash stand out from the pack, however, is Kleist’s stunning brushwork. Time and time again throughout the book he captures, in swaths of black ink and gray tones, the essence of coolness that permeated Cash’s persona. Kleist clearly studied hundreds of images of Cash and does a great job recreating his subtle mannerisms (e.g. his smirking half-smile, his pompadour hair that always seemed just a little unkempt, the way he played his guitar with his shoulders hunched, etc.).

There are also several wonderful scenes in which the artwork transcends reality for the sake of a visual metaphor. The most stunning is when Cash, sequestered in his home in order to cleanse his system of prescription drugs, endures a profound out-of-body experience. Kleist’s beautiful illustrations show a disembodied nervous system rising from Cash like a phoenix from the ashes, then hovering above him, the visual embodiment of his addiction and a powerful symbol of his spiritual death and rebirth.

In his review at Comics Bulletin, Jason Sacks described a similar scene which demonstrates Kleist’s skill with a brush. “At the nadir of his drug addiction, [Cash] wanders blithely into a cave with just a flashlight that’s low on batteries. Using blacks almost as a second character in the scene, Kleist literally shows the blackness that has come to envelop Cash’s soul at that moment in time. When Cash literally and figuratively emerges into the light, that light seems to shine straight from Heaven–a deeply healing light that reflects Cash’s emergence to finding some measure of peace.”

For all its critical acclaim (Cash won the 2007 Sondermann Prize and Germany’s top comics prize, the Max und Moritz Award, in 2006), Johnny Cash: I See a Darkness reads like an expanded version of the 2005 Hollywood blockbuster, Walk the Line. The book deepens certain elements that the movie glossed over, but rarely explores beyond the carefully cultivated image of “the Man in Black.” Like the film, Kleist focuses extensively on the Folsom Prison concert in 1968, devoting nearly a third of the book to this one event; however, unlike the movie, Kleist does a much better job capturing the tension and emotions of the day. “I think the Folsom Prison concert was one of the most exciting concerts in the history of music,” Kleist told Shaun Manning, “so that was an idea I wanted to put into the book in a large sequence. I could have done like they did in the movie, where there’s just a short sequence of the concert, but I wanted to tell the whole story of the concert.”

One of Kleist’s best embellishments was the addition of Glenn Sherley, the little known Folsom prisoner who penned “Greystone Chapel,” as the story’s primary narrator. The inclusion of Sherley, both for his relevance to the legendary concert, but also as an everyman voice for the legion of fans who felt Johnny Cash’s music spoke to them, grounds Cash’s larger-than-life story and offers a side of the man that the movie glossed over – the kind-hearted gentleman who cared deeply about his fans.

Following the trajectory of his music career, after the Folsom concert Kleist propels the story forward several decades, picking up where Cash, now an elderly man, has begun working with producer Rick Rubin on the American Recordings. This final section, although brief, allows Kleist to move past the “man in black” persona, to an extent, and show Cash’s human side.

Finally, the story ends as it began, with an adaptation of one of Cash’s songs, this time, the classic “Ghost Riders in the Sky,” the somber elegy of a cowboy left to face his demons alone. As appendices, the book also includes a ten-page “Cash Gallery” featuring gorgeous painted portraits of Cash and a bibliography of sources and song lyrics used.

As a biography, Cash is, at best, unbalanced. Like the movie, there are large gaps of time that are simply glossed over or ignored (Kleist transitions from the Folsom Prison concert in 1968 to the American Recordings, the first volume of which appeared in record shops in 1994, skipping nearly three decades). Of course, these gaps are intentional. Kleist was more interested in re-telling the legend of Johnny Cash than the complete mundane facts of his life. Kleist’s book is a compelling read – the story is boiled down to its dramatic essence – however, these omissions also leave glaring holes in the narrative. For example, there are few references to Cash’s devout Catholicism, his Cherokee heritage, no mention of his gospel recordings or wonderful children’s album, and the only time we see Cash as a family man is when he clashes with his ex-wife Vivian over their deteriorating marriage. There’s also very little about his loving, decades-long second marriage to June Carter or their children. In pursuit of the myth, Kleist’s “outlaw-worshipping spin” on Cash’s life falls far short of the real man behind the music.

Of course, none of this negates the fact that Johnny Cash: I See a Darkness is a very satisfying read, particularly for fans of the singer’s music. At its core, Faber argues that the book is “…a work of visual art and, as such, arguably has no obligation to be true or comprehensive or fair or any of the other things that we might demand of a biography.” In other words, it is enough just to gaze at Kleist’s beautiful renderings of some of the key events of Cash’s life. But the curious reader looking for a more rounded and insightful portrayal of the singer’s life might be better served by the many biographies (Kleist himself recommends Franz Dobler’s The Beast in Me) or his multi-volume autobiography.

FURTHER READING:

Michel Faber’s review in the Guardian

Paul Gravett’s interview with Reinhard Kleist

Bart Croonenborgh’s interview with Reinhard Kleist at Broken Frontier

Jason Sacks’ review at Comics Bulletin

Shaun Manning’s review at Comic Book Resources

Packaged In Black

I don’t know if it was so much [Johnny Cash’s] music per se that drew me to him; it was more his overall persona….

—Rick Rubin, Interviewed on NPR’s Fresh Air, February 2004

Unearthed, the five-CD collection of outtakes and unreleased material from Johnny Cash’s last 10 years with American Recordings, comes in a box as black and stark as Cash’s tormented soul. The sleeves are made of CD-scratching cardboard, as rough and uncompromising as Cash’s famously raised middle finger. The shrink wrap is tough and tenacious, as tough and tenacious as….

Well, you get the idea. Cash is a serious artist and it takes a virile, forward-looking, serious company like American to provide his music with the extremes of over-packaging it deserves. Old, stodgy labels like Columbia and Mercury hadn’t known what to do with a complex iconoclast like Cash — it took Rick Rubin, American’s founder, to see the greatness in Cash and act on it. The liner notes to Unearthed gleefully quote Nick Tosches, who claimed that “Johnny Cash at 61 was history, an ageing, evanescent country music archetype gathering dust in a forgotten basement corner of the cultural dime museum.” It wasn’t until Cash’s first 1994 album on American that the singer was granted “the imprimatur of ageless cool.”

Or so the story goes. Johnny Cash’s career was indeed in a slump in the eighties and early ‘90s — enough of a slump that he thought he might cease recording altogether. But he was hardly as irrelevant as Tosches and Rubin make him out to be. In fact, in 1993, the year before his first American release, Cash made a much promoted and discussed appearance on the final track of U2’s Zooropa. Rubin didn’t have to be a genius to figure out that there was an audience for Johnny Cash’s work — all he had to do was read the papers.

Nonetheless, American has spilled a lot of ink insisting that Cash’s career would have been over without Rick Rubin. The point of this strategy seems to be to make Cash and American go together like ham and eggs, or music-industry and slimeball. Usually a label promotes the artist, but with Cash and American, something like the opposite has occurred. Cash’s first album with the company was actually named American Recordings (as Cash quipped on one of his final tours, “the album American Recordings on the American Recordings label, recorded right here in America”). His other albums also give the American name unusual prominence and, continuing the trend, the back of Unearthed features the labels’ upside-down flag symbol alone on a black background. Little wonder, then, that Unearthed’s liner notes exclaim that Cash’s first album with American was “as stark, dark, and elemental as the stunning cover photo,” as if it’s some sort of compliment to Cash to have his work compared to a publicity shoot. Still, there’s a certain logic here: if the label is as important as the artist, then it makes sense that the packaging is as important as the music.

For this particular promotional strategy, the blame must rest with Rubin himself, who not only signed Cash, but also produced each of his albums. Rubin was already quite well-known before his work with Cash, in large part because he had worked on a number of landmark rap and metal albums: most notably the classic early records of L. L. Cool J, the Beastie Boys, and Slayer. But Rubin’s notoriety was also a function of assiduous self-promotion. With the Beastie Boys, in particular, Rubin pushed himself forward with unusual enthusiasm, touring with the group, appearing in videos, and adopting the rap moniker DJ Double R. According to The Vibe History of Hip Hop, Rubin considered himself a member of the band. If he believed his own hype, however, the Beastie Boys did not, and when they left his then-label Def Jam, they left Rubin behind as well.

As far as I know, Rubin has never appeared on stage with Cash, but he hasn’t exactly retired into the background either. Unearthed is presented as a collaboration between the two men, who are portrayed as something very close to equal artists. “This is the story of what happened when the man with the beard [Rubin] met the Man in Black,” the liner notes intone. Their encounter is then described in the portentous language of trashy romance novels — Cash’s former manager is quoted as telling Rubin ‘You could see the sparks flying between you two. There was such an immediate, powerful connection,” to which Rubin adds “It felt like we connected on some level other than talk.” Cash’s recollection is a bit more tongue-in-cheek. “You know, I’d dealt with the long-haired element before, and it didn’t bother me at all. I find great beauty in men with perfectly trained beards and groomed faces — or grooved faces, or whatever it is.”

Cash was intimately involved in the production of the box set before his death last September, and he’s clearly both grateful to Rubin and willing to share the spotlight with him. And there is no doubt that Rubin did revitalize Cash’s career, basically by marketing Cash the way he had marketed rap and metal acts — that is, by making Cash a dangerous outsider, a loner, an outlaw. Gone was the Johnny Cash whose biggest hits had been jokey novelty records like “A Boy Named Sue” and “One Piece at a Time”. In his place was, as the notes put it, “a dark troubadour with a troubled past who had sinned and been redeemed.” The first song on the first American release, “Delia’s Gone,” was a particularly vicious murder ballad — the video featured Cash killing model Kate Moss. Ten years before, “the dark troubadour” had appeared in a video for his song “Chicken in Black” wearing a blue-and-yellow mock-superman suit.

Obviously, Rubin didn’t invent the “dangerous loner” image for Cash, who had been singing about shooting people since the ‘50s. The American publicity merely emphasized this aspect of his persona with stark, moody, black-and-white album art and stripped-down production — especially on the first release, which featured Cash alone and unaccompanied for the first time in his career. Whatever the publicity material said, of course, Cash continued to record goofy stuff alongside the doom-and-gloom numbers. “The Man Who Couldn’t Cry” from American Recordings, “Mean-Eyed Cat” from Unchained, and, Cash’s heavenly duet with Merle Haggard on Solitary Man’s “I’m Leavin’ Now” are all glorious examples of Cash’s lighter side — wise, witty, and very funny. None of these cuts is represented on Unearthed’s fifth disc, a “Best of American” compilation which is tilted heavily towards his more solemn numbers — “Delia’s Gone,” “Hurt,” “I Hung My Head,” and the really annoying “Bird on a Wire” (Leonard Cohen’s clumsy ramblings do not benefit from Cash’s gravitas: the set also includes a fully orchestrated and even more lugubrious version.) Still, the other Unearthed discs contain a fair share of lighter material, including a jovial discussion of substance abuse in “Chattanooga Sugar Babe” and the unaccompanied “Two-Timin’ Mama,” perhaps the one American cut that most clearly evokes Cash’s Sun sides.

So all well and good: Cash is doing what Cash does, and Rubin has realized that young hipsters think it’s cooler to kill people than to laugh — or, perhaps more charitably to everyone, Rubin simply had the vision to give Cash a marketing budget, something the singer had been denied for years. Rubin, however, has not been satisfied with merely contributing to Cash’s commercial Renaissance. Instead, Unearthed’s liner notes insist that Cash’s resurgence has been aesthetic as well as critical. In explaining why he approached Cash, for example, Rubin says “I’d been thinking about who was really great but not making really great records…and Johnny was the first and the greatest who came to mind…Someone…who didn’t seem inspired to be doing his best work right now.” Rubin also says that his biggest challenge with Cash was getting the singer to see each recording date as special, rather than as just another album. The implication of all this, of course, is that the material on Mercury which Cash recorded in the early ‘90s was a series of prefabricated knock-offs.

Au contraire. The Mercury material is great — not every cut, of course, but the hit-to-miss ration isn’t significantly worse than on the American albums. At Mercury, Cash mostly worked with producer Jack Clement— a longtime friend — and he sounds relaxed and inventive. Indeed, his best material on Mercury is as good as anything he’s ever done. The duet-heavy Water From the Wells of Home from 1988 is perhaps the stand-out, featuring the lovely “Where Did We Go Right” with his wife, June Carter Cash; and the tough, vindictive “This Old Wheel” with Hank Williams Jr. Best of all, though, is the utterly bizarre “Beans for Breakfast” from 1991’s Mystery of Life, in which Cash explains that “the house burned down from the fire that I built in my closet by mistake after taking all those pills, but I got out safe in my Duckhead overalls.” Significantly, Cash never said that his work with Mercury was slick studio product: he only said, with great frustration, that the label wouldn’t promote it.

In this context, the most impressive thing about Unearthed is not how distinctive the American recordings are, but rather how much of a piece they seem with the rest of Cash’s oeuvre. For the truth is that each of the much-ballyhooed strengths of the American years — the surprising song selection, the challenging duet partners, the varied settings, and even the reinvention of Cash’s image — have all been typical of Cash’s career throughout. This is a man, after all, who started out as a rockabilly performer in the Elvis/Carl Perkins mode, appeared at the Newport Folk Festival in 1964, was associated with the Outlaw country movement in the ‘70s, showed up on Emmylou Harris’ seminal Roses in the Snow album in 1980, and had his last hit record with the Highwaymen supergroup in 1985. Along the way, he recorded songs by everyone from Ray Charles to Bob Dylan to Kris Kristofferson to Bruce Springsteen to the Rolling Stones, hosted an eclectic television show, and released protest songs, concept albums, and a novel.

Cash, in other words, was always experimenting, and it is this aspect of his work that Unearthed puts center stage. It’s an odds and sods collection, so not everything works — a couple of tracks with a mediocre blues band are a mess; Joe Strummer sounds badly outclassed when he sings with Cash on Bob Marley’s “Redemption Song”; the version of “You’ll Never Walk Alone” with organ is cluttered rather than sweeping; and I’m forced to admit that Cash’s austere renditions of hymns on disk four grow wearisome on repeated listening. That leaves, however, quite a lot of impressive music. The first disc in particular shows what a great idea it was for Cash to record alone and unaccompanied — an idea the singer had had some time ago but had been unable to sell until Rubin came along. All the interpretations are lovely: Billy Joe Shaver’s wistfully hopeful “Old Chunk of Coal,” and Cash’s own love letter to his wife, “Flesh and Blood,” are particularly fine. On the rest of the set, the duet with June is, as always, a high point; Cash’s baroque cover of his friend Neil Young’s “Pocahontas” (with mellotron) is also pretty great. Introducing Cash to Nick Cave was an obvious move, but it works wonderfully; Cave adds a touch of out-of-place gothic glee to “Get Along Home Cindy” which almost upstages the master. My absolute favorite track, though, is Cash’s short, sweet version of “You Are My Sunshine.” The song is a fusty piece of schmaltz which I’ve never liked very much, but Cash’s bleak quaver turns it from a greeting card into an agony of grief and loss.

Certainly Cash knew about grief and loss. This is the aspect of his work which — with his long illness, the death of his wife last May, and the success of the single and especially the video for “Hurt” — has been most in the news for the past couple of years. To me, though, the fact that Cash was able to change, to learn, and to take risks with his life and art for more than forty years is far from sad. One of those risks was to record with Rick Rubin, who led him to new songs, new people, new audiences, and new approaches to recording. Rubin, Cash himself, and the public all benefited from their collaboration. But I have no doubt that if Cash had not had the opportunity to take that particular chance, he would have taken another one. Even had the Man in Black never met the man with the beard, Cash’s story would still be one of the happiest in American music.

_________

A version of this essay ran at the Chicago Reader way back when.

Hard to See in the Dark

This was first published on Splice Today.

_________________________

Johnny Cash has been my favorite performer pretty much as long as I’ve had a favorite performer. When I first heard those bleeps on the Folsom Prison album, I was young enough that I actually didn’t know what was being excised. I first learned what “curfew” meant when I asked my parents what Johnny Cash was getting arrested for in “Starkville City Jail.” I’m not certain at this late stage, but I think that same song was the occasion for my first introduction to the concept of controlled substances (“he took my pills and guitar picks/I said, “Wait my name is….”/”Aw shut up”/”Well I sure was in a fix.” And no, I didn’t look the lyrics up.)

As a kid I was, like lots of kids, given to some fairly abstract daydreaming, and Johnny Cash figured in those as well. Specifically, I spent a certain amount of time wondering why people thought musicians in general, and Johnny Cash in particular, were cool. Obviously, Johnny Cash sang about shooting people and getting into fights and getting thrown in jail, and at that time he was associated with the outlaw country movement. But I knew he wasn’t actually an outlaw — he was just a singer. He didn’t even always sing about being a tough guy; sometimes, for example, he sang about political squabbles among bandmates (and yes, “The One On the Right Was On the Left” was how I learned that left and right were ideological as well as directional.) So…if he was just a guy standing up there with a guitar, what was so mysterious or special about that? I turned it over in my head on long car trips while we listened to his cassettes in the back seat, thinking of him standing on stage (I didn’t know he wore black then) and of people watching him, and wondering what, exactly, they saw when they did.