This is an essay about the criticism surrounding contemporary “subversive” and/or “satirical” comics, particularly those of Johnny Ryan and Benjamin Marra. Before I get into any of that stuff, though, I want to talk about a movie that I consider to be one of the greatest satires ever committed to film. That film, of course, is RoboCop (1987).

On its surface, RoboCop is pure machismo – a power-fantasy in which an everyman protagonist is transformed into the unstoppable, deadly RoboCop by the ominously named Omni Consumer Products. In short, he loses everything, becomes invincible, kills the bad guys, and regains his humanity. Pure pulp trash: enjoyable, violent, and light. What lies below the surface, however, is a remarkably tragic story of an individual’s loss of humanity. The care with which director Paul Verhoeven depicts the sadness of RoboCop’s circumstances, and the insane, simplistic, cold war environment he lives in, is truly subversive. Couched in the brutal excesses of a violent genre movie, Verhoeven hides an unresolved and surprisingly harsh story about the loss of individual humanity.

One of my favorite elements of the film, and I know that I’m not alone in this, is a television show which the citizens of future Detroit watch devotedly. The show comes across as a Bizarro Benny Hill, in which an unattractive protagonist named Bixby Snyder revels in sight gags and sexual scenarios, gutturally shouting his ubiquitous punchline, “I’d buy that for a dollar!” Several times throughout the movie, characters are shown watching this program, and laughing as hard as they possibly could at its non-humor. It’s uncomfortable, and represents a different dimension of excess than does the obvious violence so present in the rest of the film.

Critics have suggested that RoboCop is a commentary on America’s declining industry, and Verhoeven himself has stated that he intended RoboCop specifically as a Christ metaphor. Critics have also called it a fascist movie, and some have suggested that it is highly dismissive of female characters. There is clearly complexity in the film, more than a brief plot synopsis could provide, and more than a macho recommendation could imply. It would not be difficult to recommend RoboCop with simplistic criticism – “A movie where a man’s limbs are shot off and he’s turned into a deadly revenge-robot can’t be bad!” or “Any movie where a man is hideously mutated by toxic waste as revenge for trying to kill a robot policeman can’t be boring!” Such criticisms fundamentally miss the point, though – they’re not wrong, per se, but they would be rightly criticized as shallow for not investigating the material more deeply.

This brings me to the problems I have with the criticism surrounding contemporary alt comics artists like Johnny Ryan and Benjamin Marra. It is my opinion that there is dishonesty present in the criticism and promotion of “controversial” alt-comix, a dishonesty which not only damages the credibility of comics criticism as a whole, but leads to a hyper-defensive maintenance of the status-quo. While I single out a few critics by name in this article, it is a trend I have noticed frequently in comics criticism circles I respect. Much of my focus in this article is on criticism I have noticed in The Comics Journal, which I don’t think I’m alone in considering one of the most highly respected institutions of comics criticism today.

Jesse Pearson begins the Johnny Ryan Interview for The Comics Journal with a phrase that epitomizes the kind of criticism surrounding “subversive” cartoonists:

Ryan, over the course of his career, has acquired a significant amount of skeeved-out detractors along with an army of hardcore fans. And that’s fine. Squares wouldn’t be squares if they weren’t freaked out by what Johnny does.

This immediately established dichotomy between “fans” and “squares” is reinforced throughout the interview. In the following paragraph, Pearson suggests,

[Johnny Ryan’s comics can serve] as an acid test to see if someone is one of us or one of them. Find out where any of his fellow artists stand on Johnny’s work, and you might be able to see that artist’s own insecurities reflecting back at him or her.

In these first sentences of what is supposed to be an in-depth look at one of the more controversial cartoonists working today, the reader has learned two things. First, if you don’t like Johnny Ryan’s comics, you’re a hypersensitive square. Second, maybe the things you don’t like about Johnny Ryan’s comics are actually things you don’t like about… YOURSELF. Before the interview has even begun, Pearson is covering all of his bases. “If you disagree with anything I write from this point on,” he seems to be saying, “you are a reactionary idiot who wants to mindlessly censor anything that challenges the norm. If you agree with me, though, you’re a pretty cool guy.”

After establishing this “one of us” and “one of them” dichotomy, Pearson proposes his theory about Johnny Ryan’s satirical nature. I think it’s better for me to present the whole block of text unedited, and then deconstruct it afterwards.

Pearson writes,

I also believe that Johnny is the only true satirist at work in comics today. There is other satire—fine satire—out there. But it’s safe. Johnny is the one artist who continues to push satire into increasingly dangerous places, and that makes him a true satirist because to satirize is to tell a truth, and to tell a truth is to take a risk. Conscience and satire seem to me to be linked. Do I want to take the space to go into that much more here? Probably not. But consider that conscience is the inner voice that tells us our subjective rights and wrongs, and then consider that satire is one way to put conscience into action. Then look at Johnny’s Comic Book Holocaust series of strips and zines, in which he lampoons everything from indie heroes to classic funny-papers staples. The satire in these stories is so utterly disgusting and base, the drawings so ham-fisted and ugly, that it’s almost a satire of satire. Johnny, you see, is smarter than he’d like people to think.

When I first read Pearson’s interview with Johnny Ryan I had not read much of Johnny Ryan’s work. As a result, Pearson’s assertion that the bulk, if not all, of Ryan’s work is “satire” seemed plausible to me – the things I’d read were the parts that weren’t obviously satire, then. As such, the assertions about risk-taking and truth-telling were reasonable to me. What slowly dawned on me as I read the rest of the interview, though, was that the assertion of “truth telling” was never backed up; the context of the satire was never particularly examined The only contextualization of Ryan’s satire that Pearson offers is that it’s not “safe” – again letting the reader know that if he/she doesn’t like Ryan’s work then he/she is a wimp.

The part of that paragraph that infuriates me the most has to be the smug phrase “…it’s almost a satire of satire.” This is presumably the point at which the people who “get it” all implicitly understand exactly what Pearson means, and the squares all shit themselves in fear and disgust. It is unthinkable to me that Pearson so casually suggested that Johnny Ryan’s art is a “satire of satire” and then absolutely failed to back up that statement in any way, because the implications of that statement are staggering. Johnny Ryan comic you like? Satire. Johnny Ryan comic you don’t like as much, due to its disgusting art and content? JOKE’S ON YOU, ASSHOLE! IT’S A SATIRE OF SATIRE!

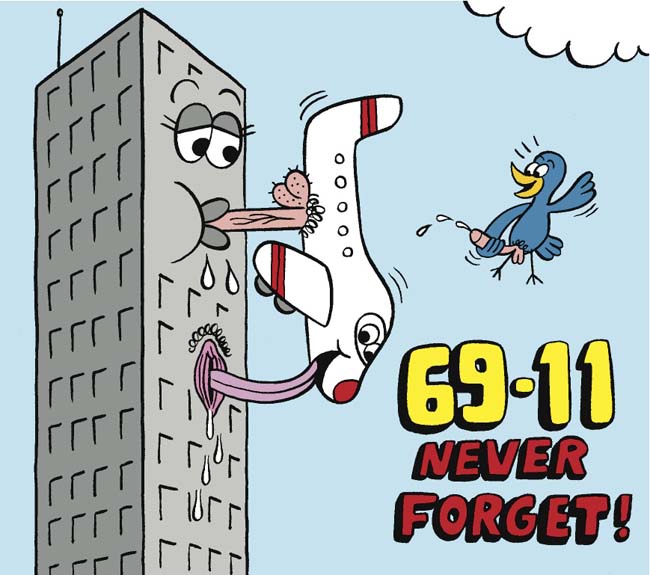

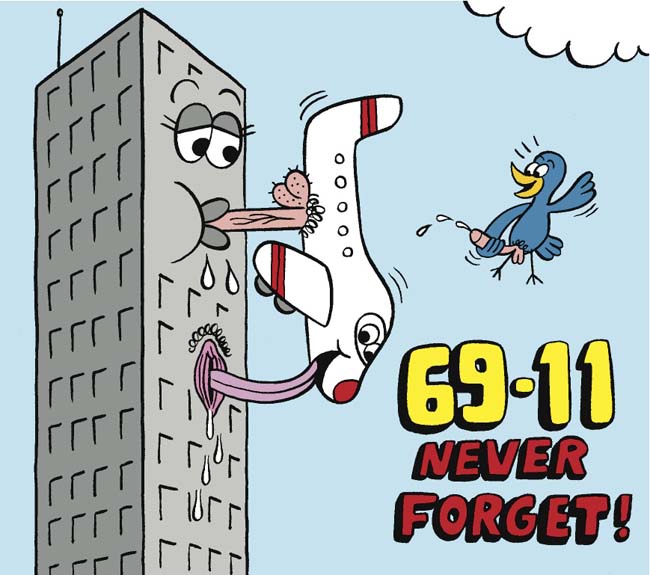

Joking aside, here’s my problem with the idea of Ryan’s work being called a “satire of satire,” or even being called “satire.” I’ll start by assuming we’re all using the conventional definition of satire here (satire is when “vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, ideally with the intent of shaming individuals, and society itself, into improvement.”) That definition seems to hold up to Pearson’s ideas about conscience and truth telling being related. So given that definition, how is Ryan’s infamous “69-11” drawing satire?

What shortcoming is being mocked by this drawing? If the figures were of George Bush and Rudy Giuliani engaged in furious 69ing I would buy the satire (their cyclical, masturbatory exploitation of national tragedy for their own ends) but as the drawing stands, I cannot see satire in it, really. And before someone says, “he’s mocking our society’s sensitivity, man!” I have to ask, is he? I get that he drew this specifically to make people mad, but if the sole end of the drawing is to make people mad, that’s not really satire, is it? Nobody’s shortcomings are being held up here, really. This is just trolling and potty humor, as far as I can tell.

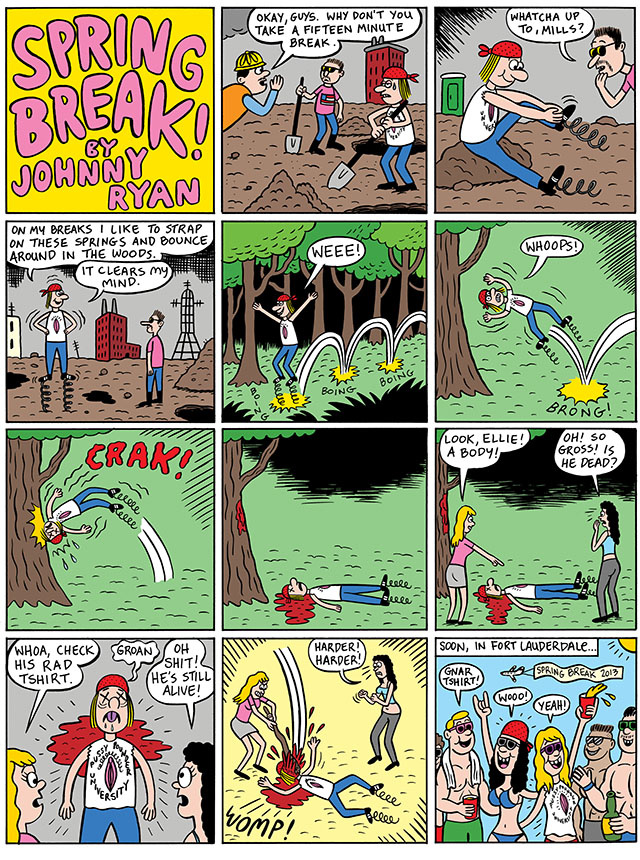

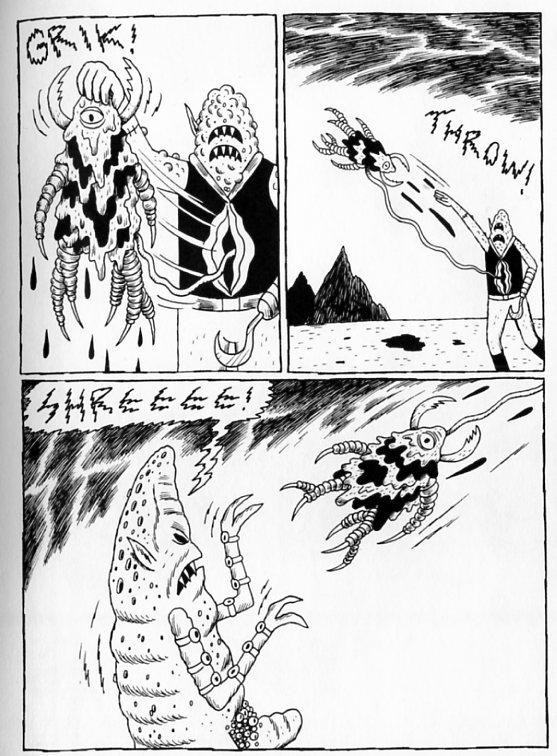

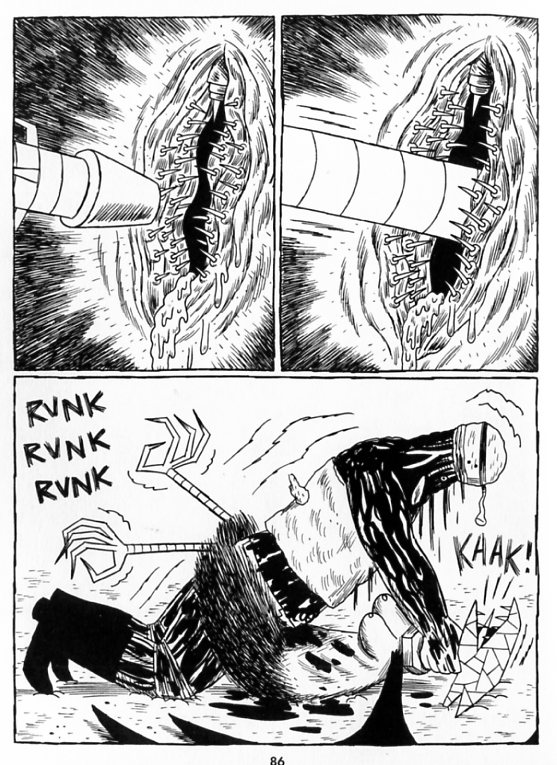

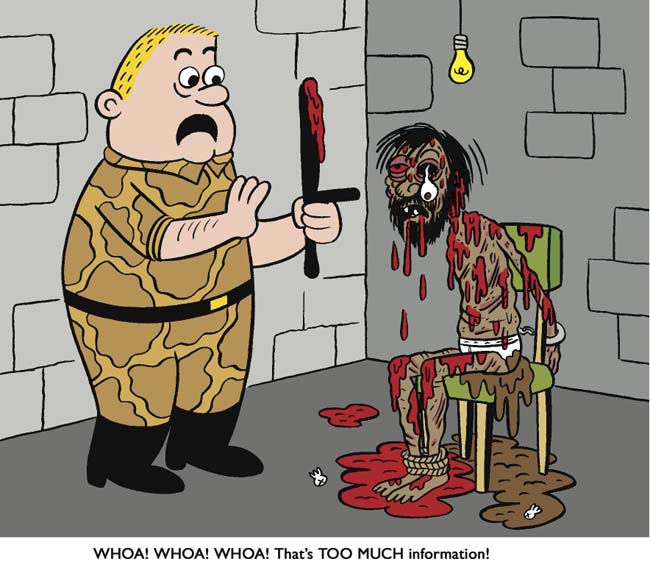

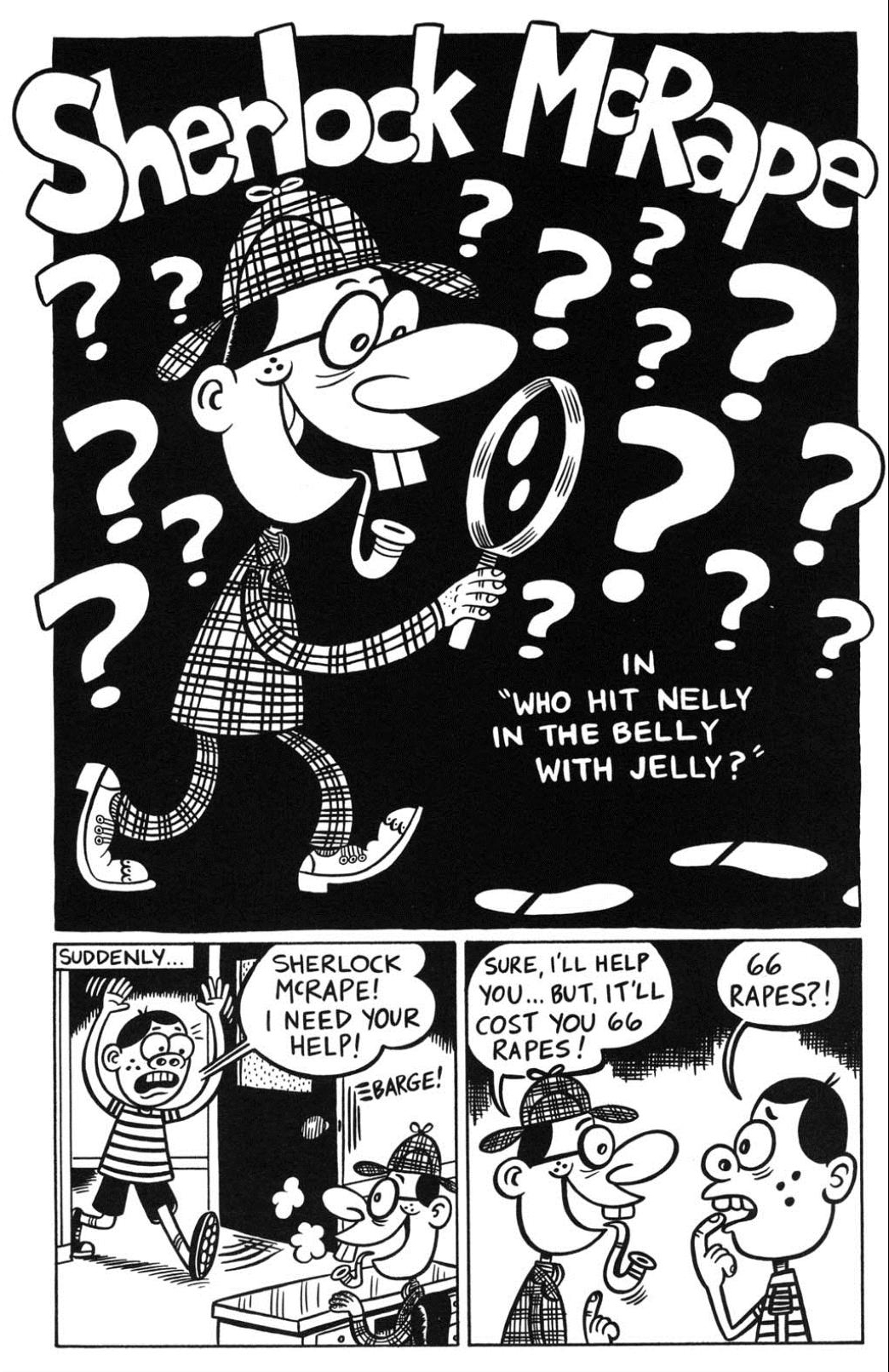

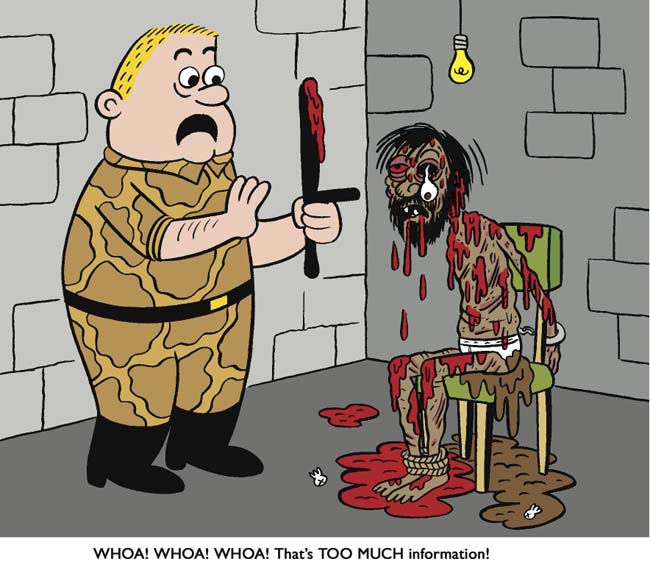

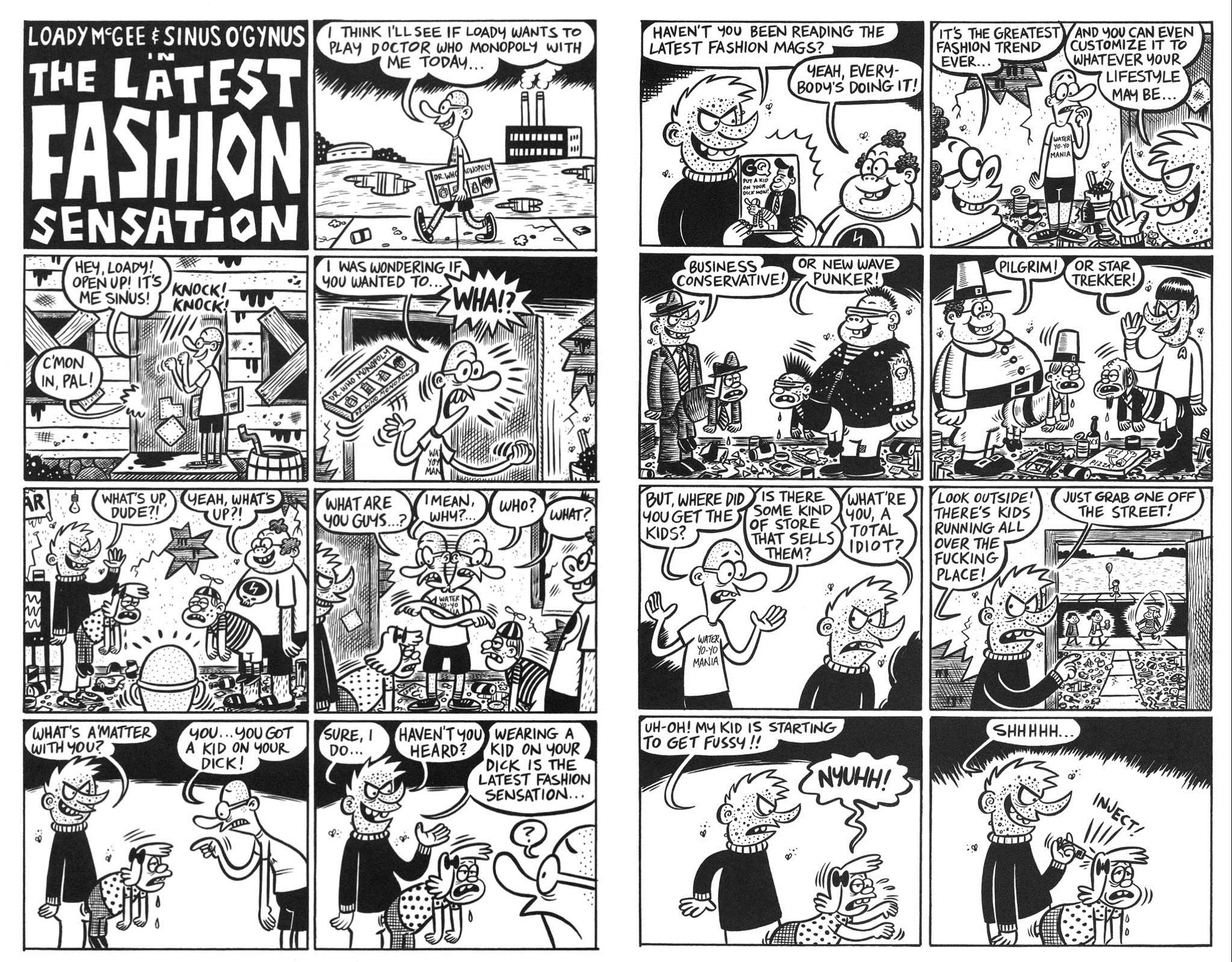

But maybe that was the wrong drawing to consider. Here’s a more straightforward Ryan “satire”:

Alright, I can buy that there’s satire here. The problem that I have with it, like with many other Ryan cartoons, is that I don’t think it’s particularly good or interesting. Remove the shit and blood from the detainee in the chair, and you have a standard Johnny Hart or New Yorker type cartoon. With the blood and shit, though, what’s added to this drawing? The viewer isn’t confronted with the horror of a torture chamber, particularly – Ryan clearly gets off on drawing the gore, and everything is abstracted past the point of losing its impact. Pearson talks about the anger behind the drawing, but honestly that doesn’t come through to me either. Ryan’s style is terminally cold, and his figures so generic and disposable that the reader is hardly motivated to care about them.

Given my feelings about this drawing’s failure as satire, it’s worth considering whether it is “satire of satire.” Is this a parody of Hart or the New Yorker cartoonist who would draw a clean, sanitized torture scene, and attach a stupid punchline without considering the humanity of real torture victims? It’s a valid question, and I am going to again say, no. What this drawing lacks, that a good “satire of satire” would have, is context. If Ryan was engaging in a Colbert-type mock identity, like The Onion’s cartoonist does, that would be context. If a character in one of Ryan’s comics misguidedly produced this cartoon, that would be context. What does context add to satire? Simply, context adds the target of derision necessary for satire. “Too Much Information” in the context of The Onion becomes a critique specifically of hack cartoonists. I could actually see The Onion publishing 69-11 (it’s not like they don’t publish intentionally controversial artwork), but they might publish it under an “alternative cartoonist” alter ego, which would provide context. Effective satires, like Black Doctor or Colbert or All in the Family or California Uber Alles or I’d Buy That for a Dollar! are effective due to their contexts.

Johnny Ryan’s saitre, if you can call it that, seems to be generally proving a single point: “Our values and beliefs about the world are constructions!” So, for example, offense about 9-11? It’s constructed, man! Political correctness? Where’d that come from? And why does everyone get so offended when I mock rape victims? Johnny Ryan says,

If I come up with an idea that makes me think, “This is going to fucking piss people off,” it excites me. I don’t know what it is, but irritating people is fun. [laughs] It’s fun to hit those targets that are sacred or that are so innocent. People are like, “Why are you picking on this person?” … There are certain people that I feel like they get it, and mostly it’s guys that get it. But there are exceptions. There are women that get it. I find it surprising that some people are so sensitive.

If that’s the satire everyone is so crazy about, I again have to say that it’s not good or effective satire. The point of satire is not pissing people off solely to piss them off, it’s to do it to prove a larger point, and there really doesn’t seem to be one beyond “our society is too sensitive!”

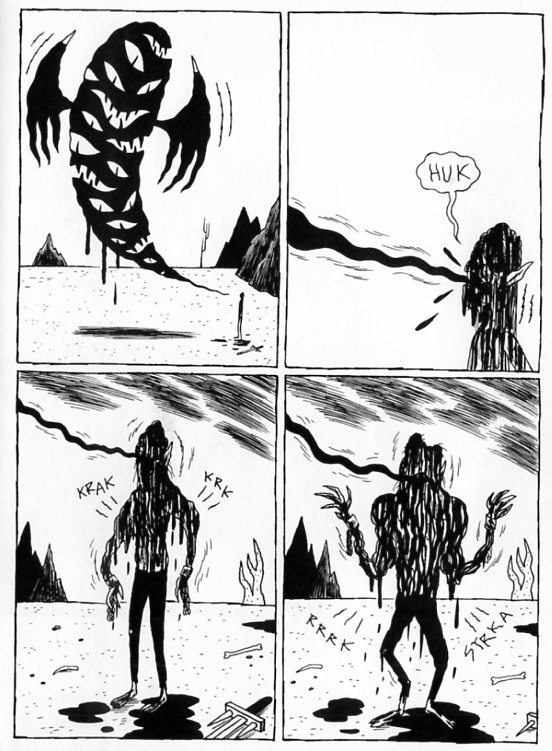

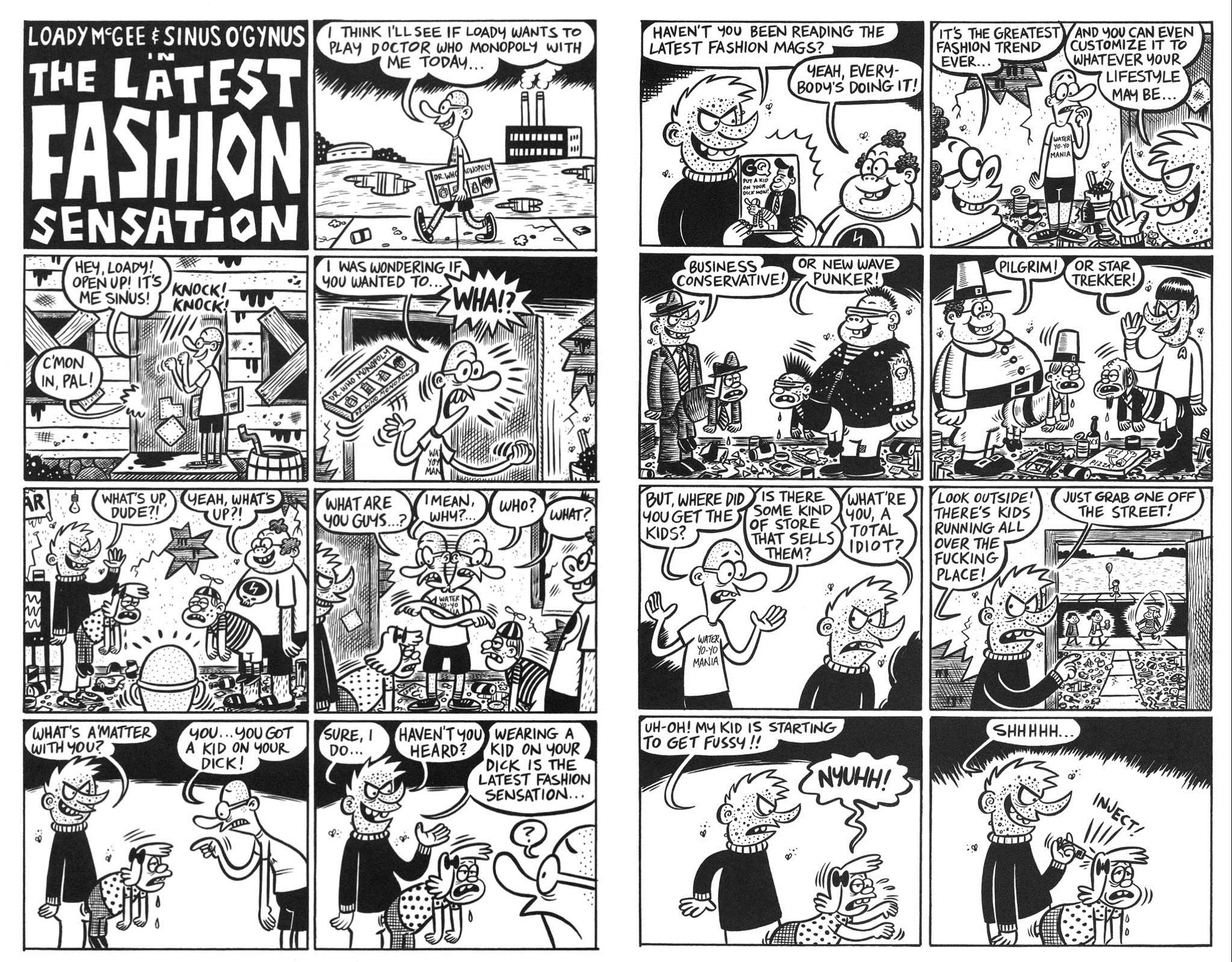

Without the context necessary for me to call Johnny Ryan’s cartoons “satire,” what are they? You’re left with lowbrow humor and throwaway plots, which aren’t necessarily a bad thing. It reads like The Beano, but with poop jokes! Why do people constantly insist on calling it “satire” anyway?

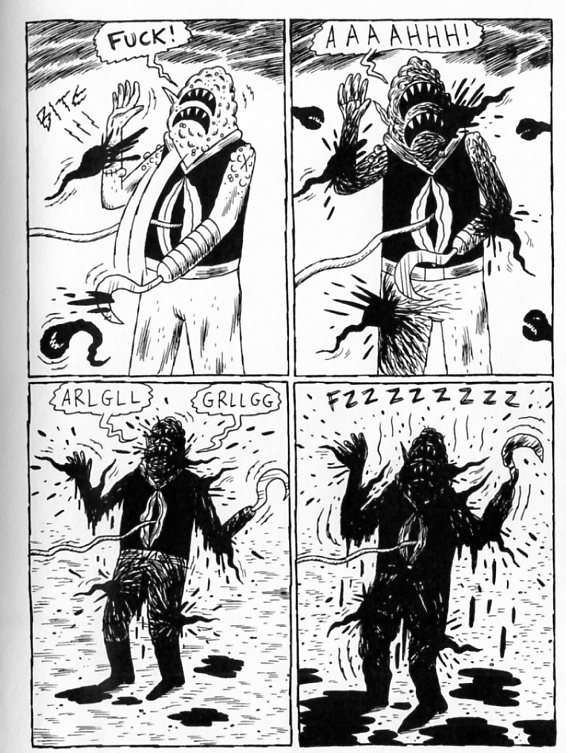

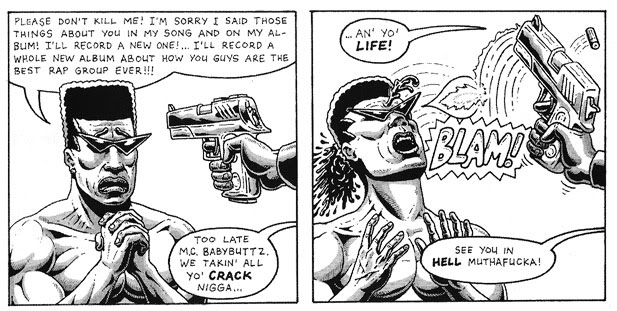

Oh, right. Because without “satire,” Johnny Ryan’s cartoons come across as disgustingly racist,

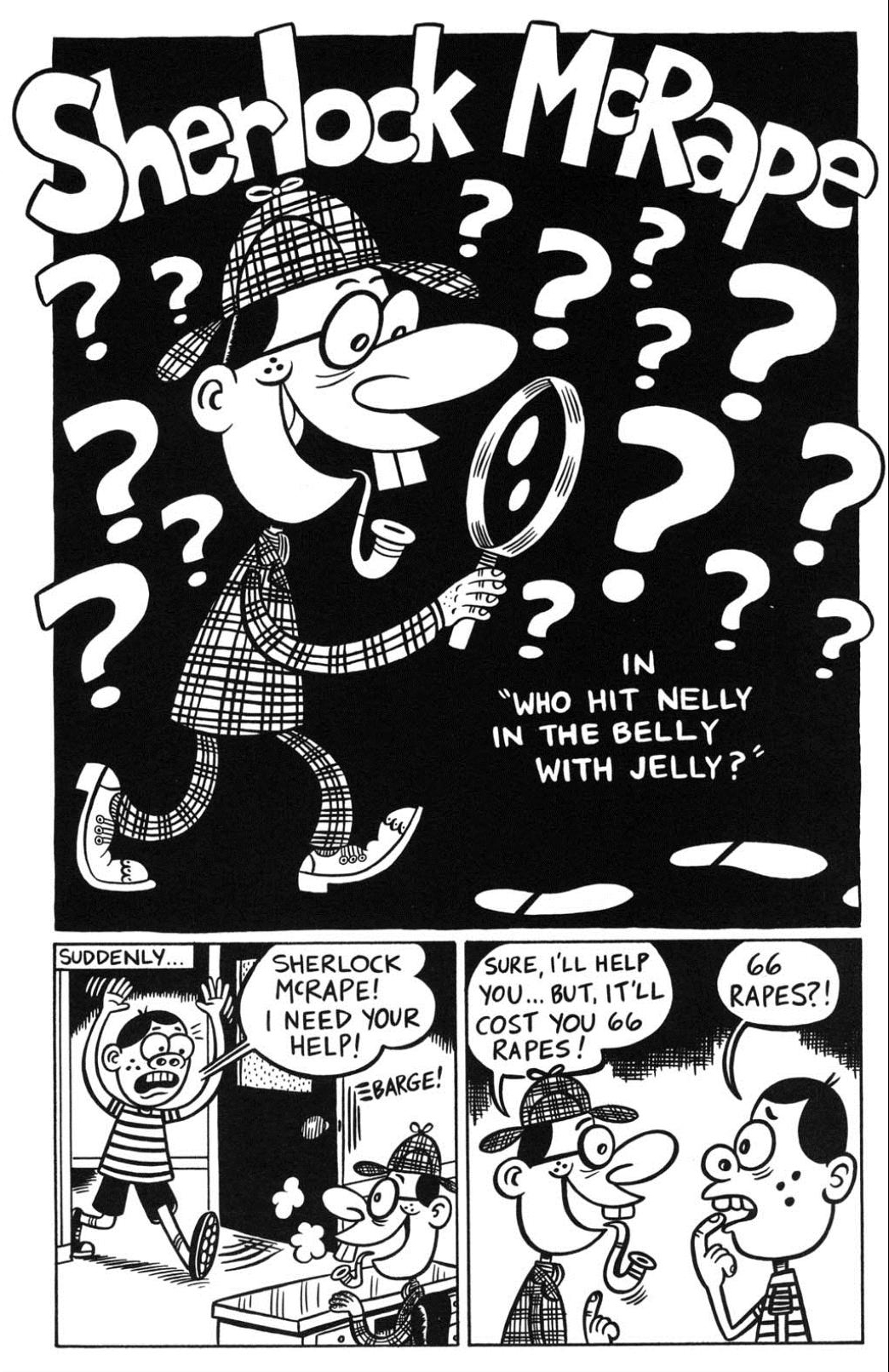

Misogynistic and violent against women,

And a whole lot in-between.

“Satire,” it turns out, has been adopted as the perfect defense against people who take issue with the content of Ryan’s comics. Of course, it could be a legitimate defense if it were backed up in any way. I have respect for well-composed arguments that make a legitimate effort to show the satire in something. Here’s what I don’t have respect for: “People need to chill out, it’s satire and it’s just too much fun to really take offense!”

I’m not asking for anything more than a better defense of the word “satire” when used to describe Ryan’s comics, and an openness to actual critical discussion about them. Right now, it seems mostly like people work backwards when reviewing his comics. “Here’s a Johnny Ryan cartoon I think is funny, but it’s racist. Johnny Ryan cartoons aren’t racist, so it must be satire!” “Here’s a Johnny Ryan cartoon that I don’t understand. It’s not really satire, but Johnny Ryan isn’t a bad cartoonist, so it must be a satire of satire!” Instead of always needing to be part of the ‘cool crowd’ who ‘gets it,’ it should be ok to ask critical questions. And when interviewing Johnny Ryan, maybe it would be better to be a bit critical then to have this infuriating exchange:

When is it ok to start making jokes about something atrocious like 9-11?

Well if it didn’t happen to me, then we can do it right away. [laughs]

I think I agree.

“I think I agree.” Wonderful. Way to “get it.”

Now, I’m not getting upset over this in a vacuum, and I don’t want to direct all of my frustration towards poor Jesse Pearson. Look at almost any review of Ryan’s books, and you’ll find someone calling his satire a triumph, and his comics hilarious. Hilarious is a matter of personal taste – just because I find Ryan’s comics excruciatingly boring doesn’t mean everyone should, and I can’t begrudge people for enjoying things I don’t. What I don’t care for is the aggressive assertion that I should find Ryan’s cartoons hilarious or fuck right off. And I especially don’t care for it when, rather than being told to fuck off by anonymous google reviews, I’m told to fuck off by The Comics Journal and other cartoonists who should know better.

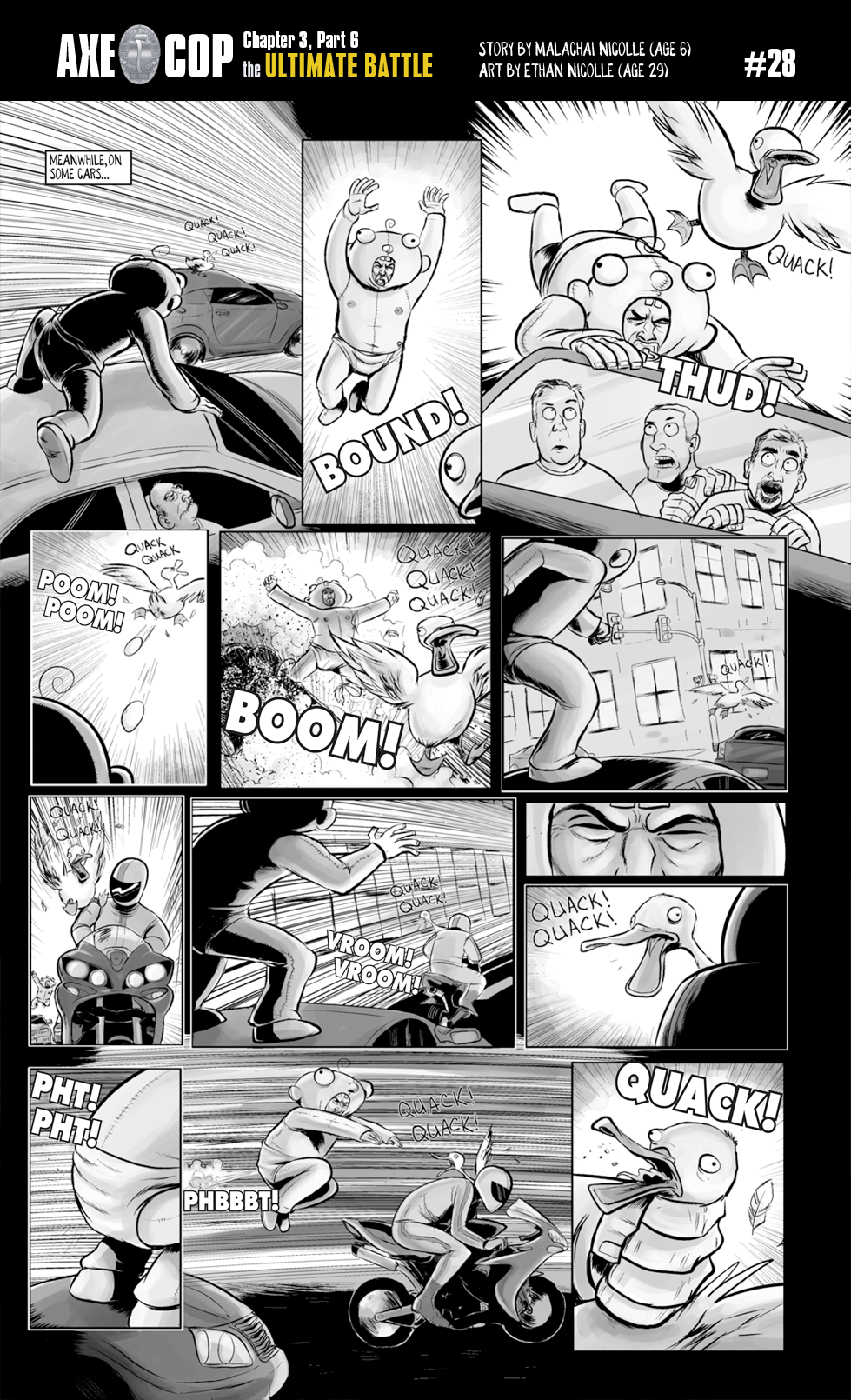

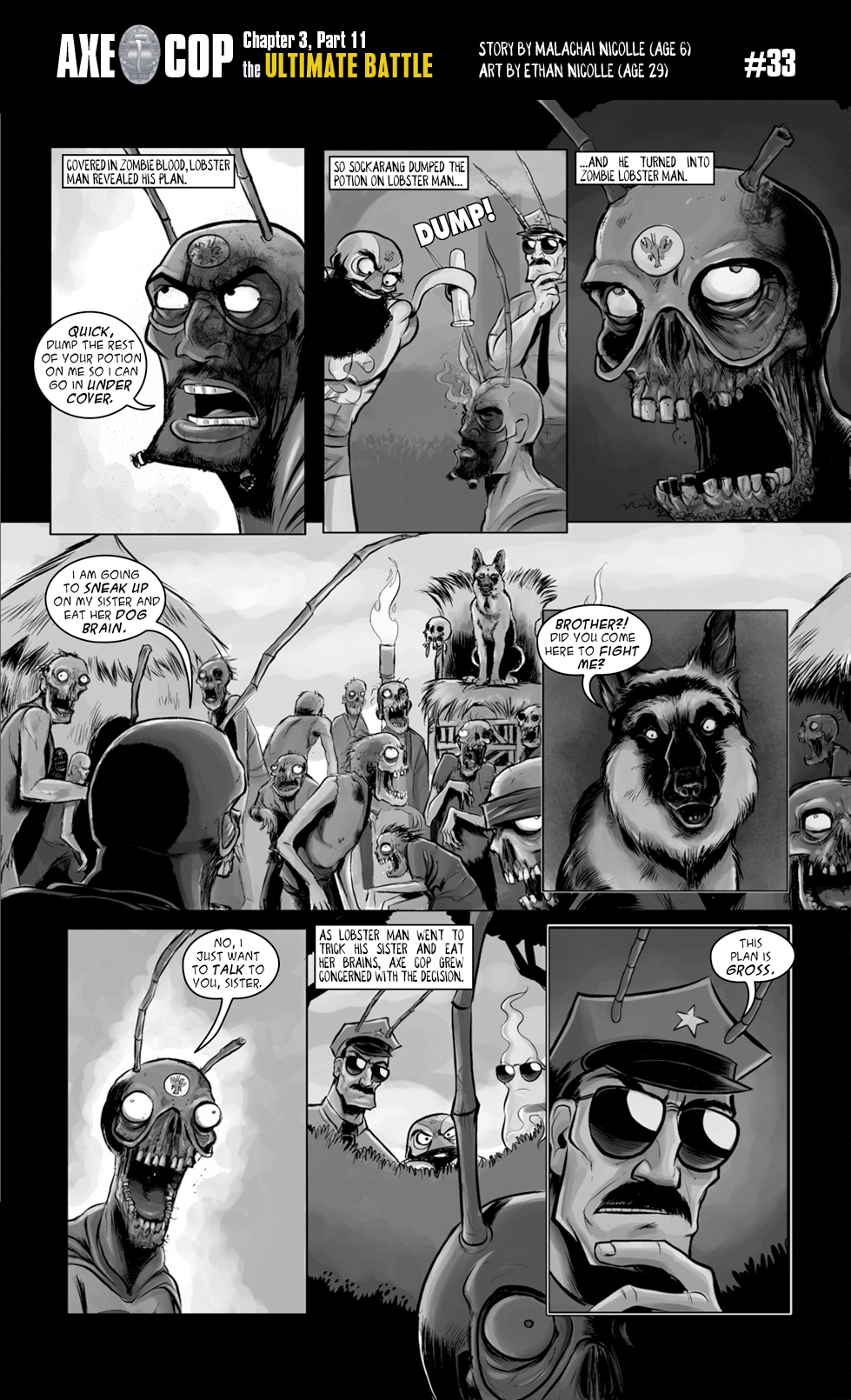

“It’s hilarious, fuck you” isn’t a sentiment limited to Johnny Ryan’s comics. Matt Seneca’s interview with Benjamin Marra for The Comics Journal and the subsequent commentary that arose from it again fall into this trap of assertion. Throughout his review Seneca blends assertions of satire and hilarity with the other overwhelmingly common trend in alt-comix criticism, which centers around a type of hyper-congratulatory mock masculinity. From Seneca’s opening paragraph:

Once you meet the artist behind the gloriously pulpy action-crime pamphlets published by Traditional Comics, you wonder how you ever felt you understood his work before. Benjamin Marra’s gregarious, genuine, and permanently enthusiastic personality has become inextricable from his art for me. In an alternative-comics milieu which prizes creations that foreground their creators’ deepest neuroses, comics like Night Business, Gangsta Rap Posse, and Lincoln Washington are the antidote we never realized we needed: brash expressions of unfettered Americana and masculinity, an earlier breed of comic-book storytelling reincarnated to take advantage of the modern medium’s disdain for content restrictions. Ben’s comics are explosive orgies of blood and sex and fire, but the hand behind them is probably the surest in the game at the moment, the product of a rigorous art-school education that pulls inspiration from the chapels of pre-Renaissance painting and highbrow modern art as well as the trash bins of comics history.

Seneca’s first sentence comes across as wildly defensive to me. “You think Marra makes racist comics?” it asks, “well your opinions are invalid because I’ve met him, and wow, he’s such a good guy.” What happened to the death of the author? This problem exists in the Johnny Ryan interview as well (and any time any cartoonist is criticized harshly, it seems like) – “Come on, guys! Cartoonist X is so nice, why do you have to attack him/her?” I’ll put my feelings towards it this way: if a reader has to know your life story, your intent, and how nice a person you are in order not to dislike or “misinterpret” your story, you have failed as a storyteller.

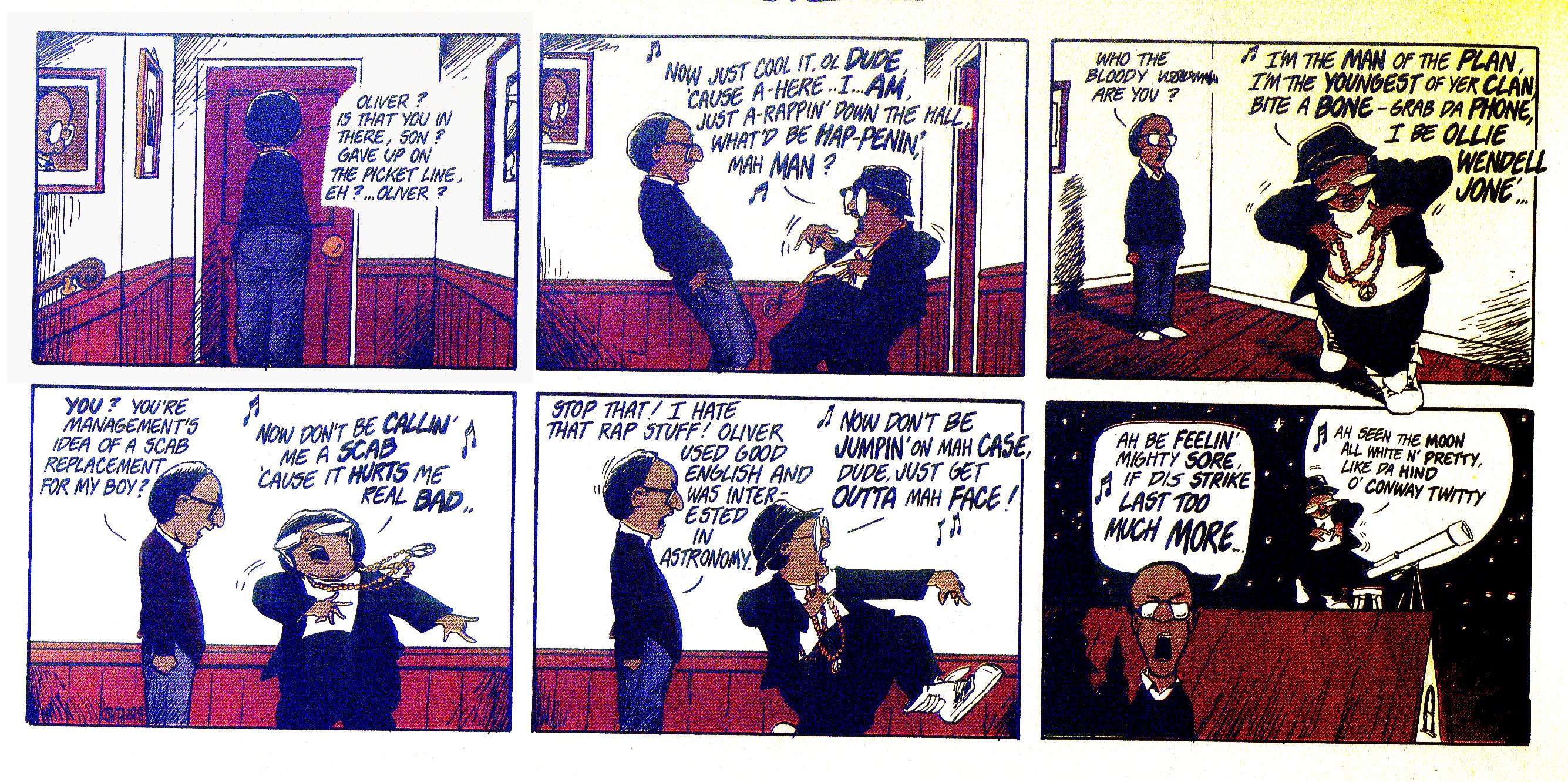

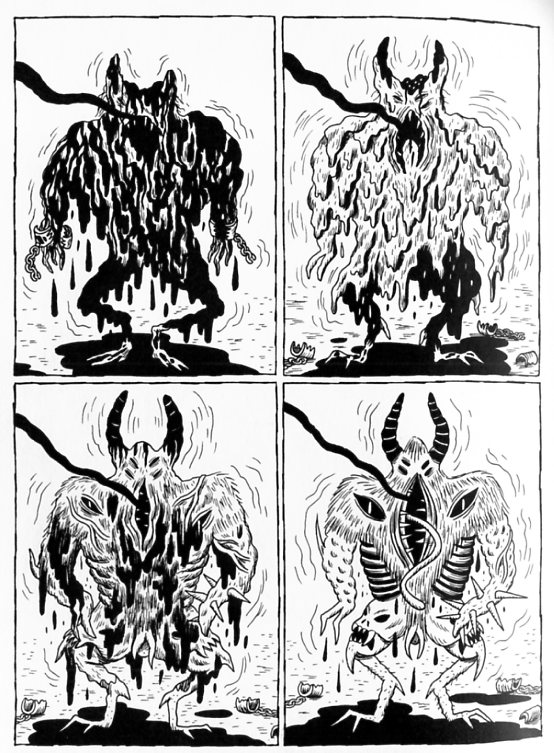

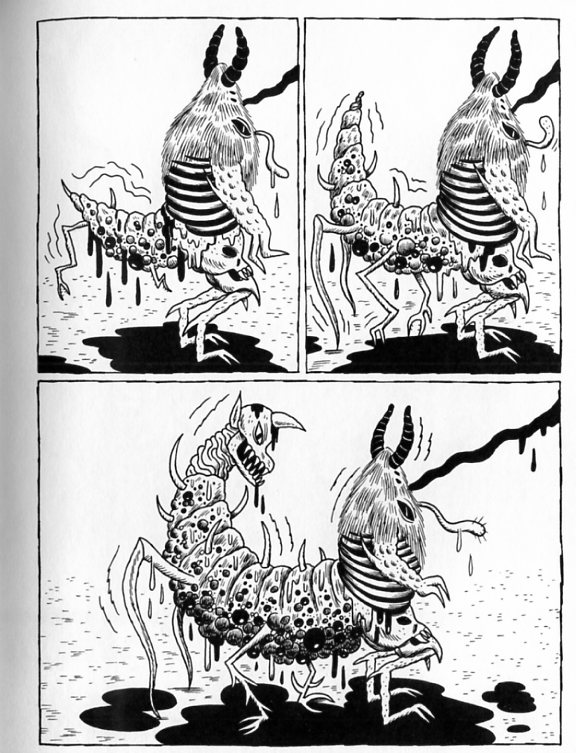

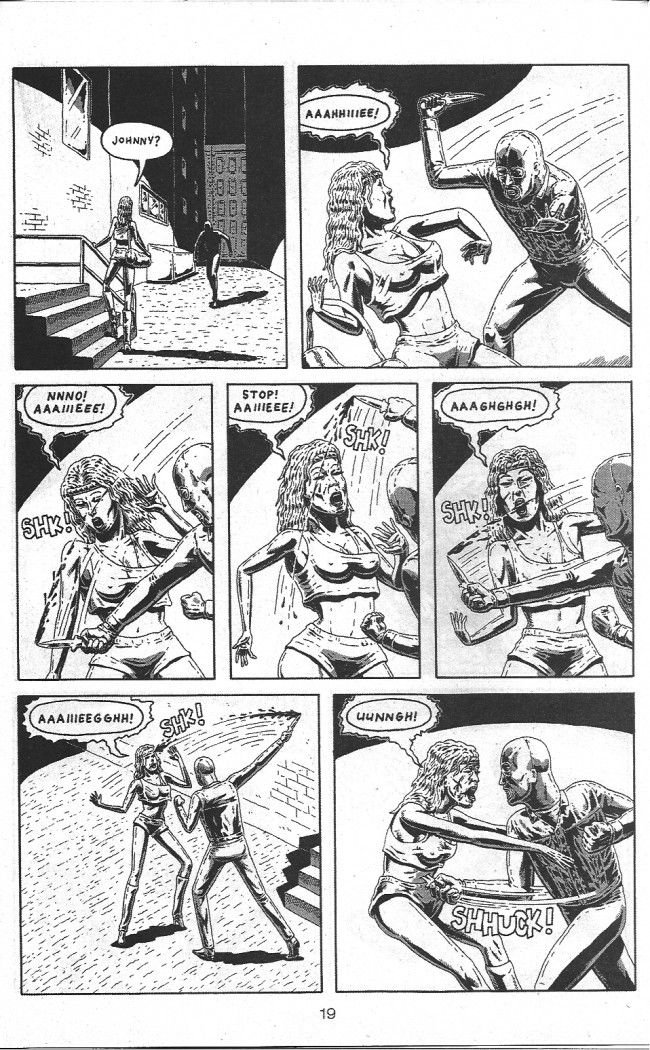

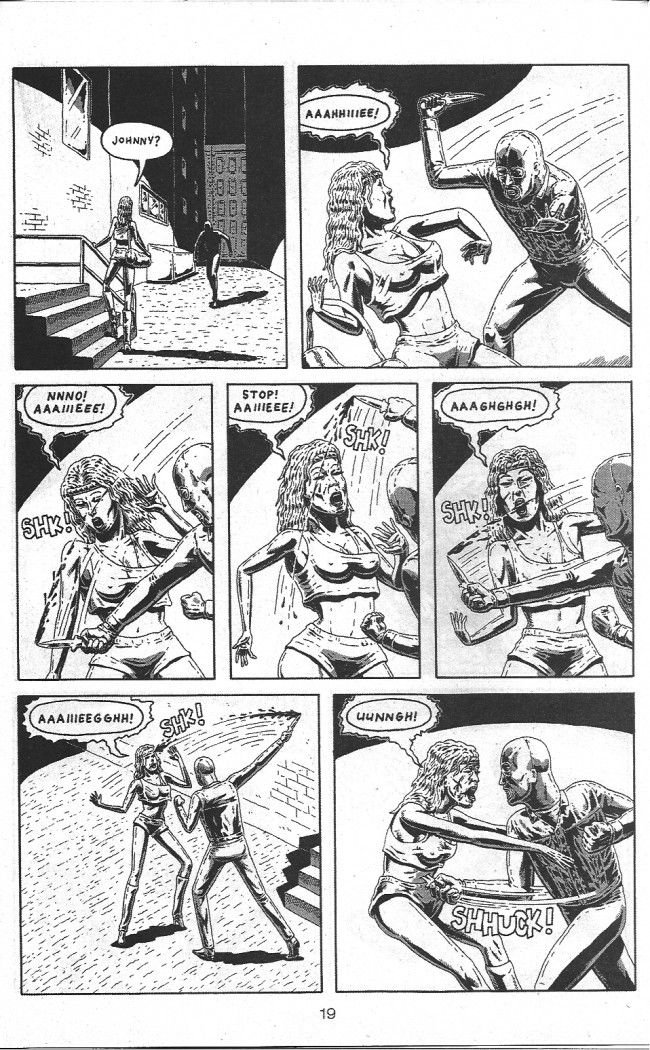

Back to the opening paragraph! Seneca goes on to hit the usual target – the universally hated, whiny, autobio comic – and informs us that Marra’s comics are the antidote we never knew we needed, a callback to pre-comics code pulp and violence! OK! Great! And what do these comics look like?

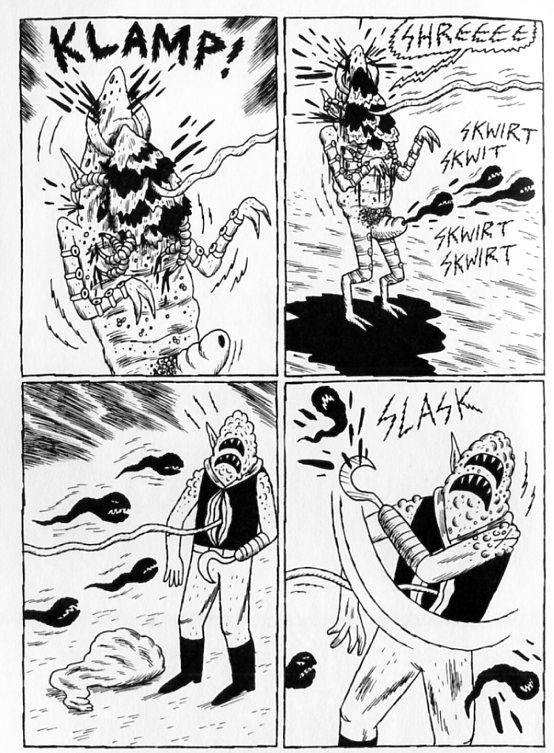

Well, it looks to me like gratuitous, almost fetishistic violence against women, and some horrible racial stereotyping! Marra says,

Comics should embrace the idea of being exploitation. Low level, gutter-trash entertainment. That’s what I was trying to make with Night Business. If you’re trying to make a gritty comic, have fun making it as gritty as possible. As nasty and gory and sexy and filled with the most base human emotions as possible. Don’t try and make it reflect come (sic) kind of reality, like they do in these superhero books.

Alright, so Marra, by his own stated purpose, is just trying to make comics that will be fun and fucked up. No sign of satire, really, especially when he says, “Night Business was all about power, all about revenge. The main characters don’t have any kind of doubt … I want [to be the fantasy of what I could possibly be in my dreams, you know?” That’s fine, and attaches a kind of earnest sincerity I appreciate.

That said, it does open Marra up to some obvious criticisms. Why do you consider violence against women “fun?” Why do you think comics are a solely exploitative medium? Why do you defend your racially charged comics as ironic, but stand behind your hyper-macho white-people comics as sincere?

Instead we get this question:

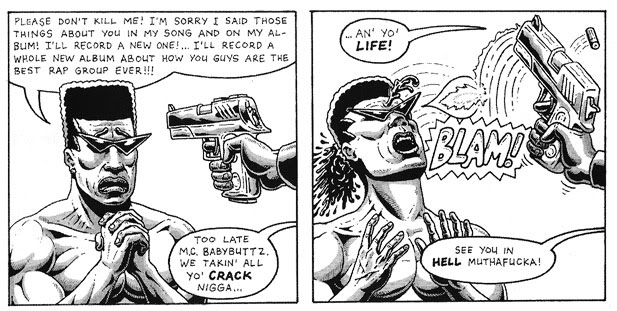

SENECA: All right, so then you came out with the first issue of Gangsta Rap Posse. Did you conceive of that, and your Lincoln Washington comic too, as highly racialized comics from the beginning, or did you just want to do fun riffs on black culture and N.W.A.?

Alright, Seneca. That’s trying too fucking hard to be forgiving. What, may I ask, is the difference between a “highly racialized comic” and “fun riffs on black culture” when we’re talking about Benjamin “low level, gutter-trash entertainment” Marra?

Marra’s answer is almost as infuriating as the question itself. He attributes his wanting “to do an N.W.A. fun thing,” to a VH1 Behind the music documentary he and his friends watched, which is possibly the least personal reason to do anything. The really irritating part comes when Marra sets the tone for the rest of the interview by preemptively making excuses for why he’s allowed to be racially problematic.

I don’t think you can really do [comics about gangster rap] without it being really racial, because that (sic) what it’s about. And I knew if I was gonna do it — it’s the same lesson I learned as a developing artist, you just can’t censor yourself in any way, especially when it comes to that kind of material. I just knew I had to do it as honestly and as… it’s weird to say respectful of the material, but that content demands that kind of outrageousness. I felt like if I had done anything different it would have been weak and dishonest and insincere. … Also, if I have these story ideas, I can’t censor myself or else I won’t do them, because I won’t think that it serves the artwork in the end if I try to water it down based on this illusion of how I think people will react. That’s not a viable gauge to base decisions on, because it’s not real. It’s only real after. I can’t imagine what people are going to say, I just have to do it and see what happens. To me it’s about serving the work, and gangsta rap is gangsta rap. There’s nothing that’s in the comics, I think, that isn’t so outrageous that it’s not already in the lyrics.

The concept that Marra can believe a work of art is racist (or at least racially problematic) but that his “respectful” riffs are somehow absolved of all responsibility or criticism is gross. The idea that he can’t censor “in any way” is bullshit – as Nate Atkinson pointed out in his earlier HU piece, it’s intellectually lazy to claim no responsibility for one’s actions while simultaneously thinking critically about how to lay out a story. What, a reader might wonder, is his goal with these stories? Why does he make such intentionally inflammatory comics?

It goes back to how I think about comics and what I think they should to. I was on a panel recently with Johnny Ryan and we were talking about controversial comics, horrific things in comics. Someone asked what he thinks about comics these days, don’t you think they go too far… I can’t remember exactly, but his response was really great, he said he didn’t think comics go far enough. Because nobody pays attention to us anyway! The only way that anybody would pay attention to comics is if they actually had a story that people wanted to talk about. But they don’t! I mean, people in the comics community wanna talk about them, but it’s very rare that anyone else does. At least, that’s my perspective.

The lack of logic on display here is horrifying to me. Let me get this straight, Marra and Ryan don’t think comics get enough attention. They’re marginalized. So, their plan to get people to pay attention to comics is to make the most alienating niche comics possible? How does that make any sense? Even if their goal was accomplished, and Ryan or Marra’s comics achieved Piss Christ-level notoriety, don’t they think that would hurt alt-comix in the long run?

It’s not a question we’ll ever get an answer to, because Seneca doesn’t want to be a buzzkill. Instead we are treated to increasingly desperate rationalization from Marra, increasingly dubious claims that he’s really not responsible for anything he says or does. Marra says,

Gangsta Rap Posse is underground comics, it’s not on a lot of people’s radar, but the things is, I’ve never gotten anything but a positive reaction to it. I’m sure if it was distributed to a much wider audience it would get a really negative response, if people took it seriously — not as satire, not as a comment on myself as a white suburban artist making a comment on black urban culture from a specific time period. I think people might react negatively.

Ah! So there is our satire. Gangsta Rap Posse is a comment on Marra as a white, suburban artist making a comic on black urban culture from a specific time period. It’s satire of satire! It’s satire of satire of satire! As long as I’m not a racist, ok? When I make comics about white people, they’re earnest and cool power fantasies, and when I make comics about black people that read almost the same, but have the N-word a lot, those are satires. It’s OBVIOUS.

Sorry, do I sound bitter? Maybe it’s because after Marra said that, Seneca didn’t call him out. Seneca, in fact, asserted that Marra is “doing it from a positive place,” as if that means anything. Maybe it’s because Darryl Ayo wrote maybe the mildest condemnation of Marra I could imagine, and was dismissively mocked on The Comics Journal’s site in response. Maybe it’s because pretty much every criticism of Marra and Ryan has been met with the statement that people need to learn to take a joke.

What do I want? I want Benjamin Marra to own up to the fact that he has created comics that could be viewed as racially problematic. Just own it. And I want Johnny Ryan fans, and Benjamin Marra fans to own it, too. They don’t have to stop reading Johnny Ryan, they don’t have to stop reading Benjamin Marra, they don’t have to stop consuming media that I consider racist or misogynistic or homophobic. They just have to own it. “Yes, I like comics that I’m able to enjoy from a position of privilege.” “Yes, I think these comics centered around extreme violence against women and children are hilarious.” Don’t bullshit me with your claims of satire until you’re able to back them up, because satire isn’t a magic word that makes critical thinking disappear.

Ultimately, I think criticism along these lines hurts comics. It makes comics critics look like macho assholes, and it gives lazy artists an excuse to make “shocking” comics that are as intentionally hurtful as possible without any critical thinking. I bought both issues of Suspect Device, recently, after reading KC Green’s submission, and I was thoroughly disappointed. Those slim volumes contained simultaneously some of the most revolting and boring comics I’ve ever read. And it’s our fault, everyone’s fault, for continuously reinforcing the idea that political correctness must be not only avoided, but willfully destroyed, that the uglier and grosser and more shocking you can make something the more brilliant it is. Ultimately, we’re going to end up with a lot of really boring comics. Look, it’s ok to get excited that Al Jaffee likes Johnny Ryan’s comics, but think about it – Ryan’s comics are pretty much Al Jaffee comics with a little shit and semen sprinkled in. I’d rather see something new.

It’s important to reiterate that I don’t think Johnny Ryan, Benjamin Marra, or any other artists should stop making controversial or “edgy” comics. I believe they have every right to make comics, and don’t think their comics should be banned or censored. I also believe, however, that any reader of their comics is entitled to a response. In my introductory paragraphs I made a lot of assertions about RoboCop, and it would be entirely within another reader or critic’s rights to call me out on any of them. And hell, I’ve written sloppily and told stupid jokes in my time, and it is anyone’s right to call me on that. That’s how good criticism functions – when it’s part of a larger conversation, when readers don’t simply accept sweeping statements bluntly presented as capital F “Facts,” and authors are open to the possibility that they aren’t as clever as they think they are.

When Marra treats black culture as a playground he can detachedly plunder at will, or when Johnny Ryan jokes about ice cream being referred to by martians as “nigger shit,” it doesn’t take a critic to point out that it could be problematic. When Johnny ryan’s punchlines revolve around women being violently raped, and Marra devotes an entire page to lush and detailed drawings of a woman being slashed by an attacker with a knife, it doesn’t take a “hyper-sensitive” reader to want to delve deeper into the narrative and/or contextual motivations of the author. What happens, though, is that a reader or critic raises the question, “is it actually funny?” or “why is this satire?” and is shut down quickly and brutally by the greater comics community. This needs to stop. We’re better than this, and I thought we were smarter than this. If we’re going to be taken seriously, we need to take comics seriously and stop excusing lazy and hurtful thinking.