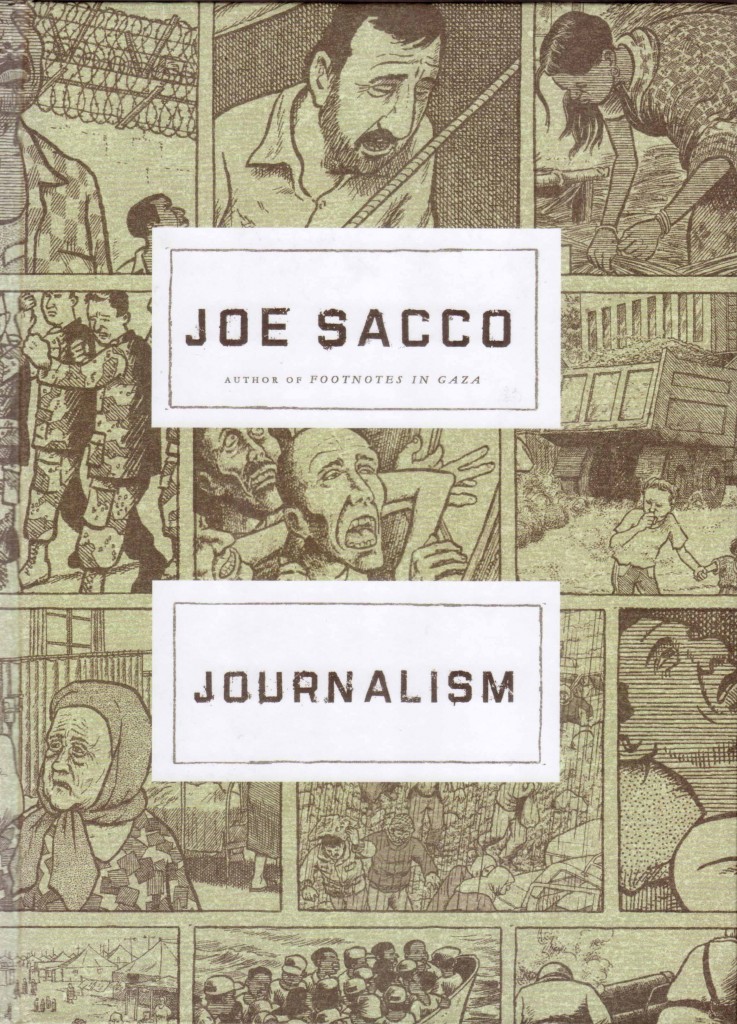

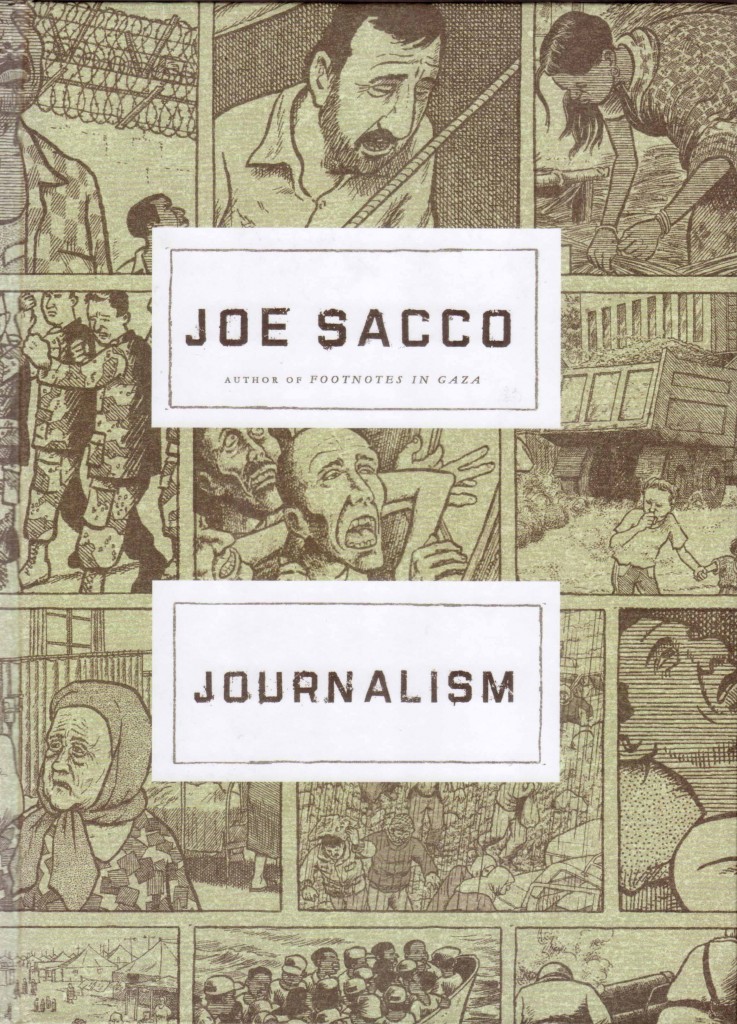

Joe Sacco’s Journalism collects some of the author’s shorter work which first appeared in various magazines, newspapers, and books. Only those utterly devoted to Sacco’s output are likely to have seen every one of these stories and even in that instance, their compilation in one ready volume should be most welcome.

While Sacco isn’t exactly coasting, he seems to have settled into a certain groove over the past decade—a sure-footed method of attack and transcription that ensures a minimum level of quality. Despite the title of this new book, Sacco’s work here can be more precisely described as reportage which focuses on persons as opposed to the grand scheme of things. This label should not obscure the fact that he does steer his stories in fairly predictable directions while infrequently providing direct opinion (in contrast to the prose form afterwords found in this anthology). He almost never offers up solutions to the problems he encounters and purposefully shuns overt editorializing.

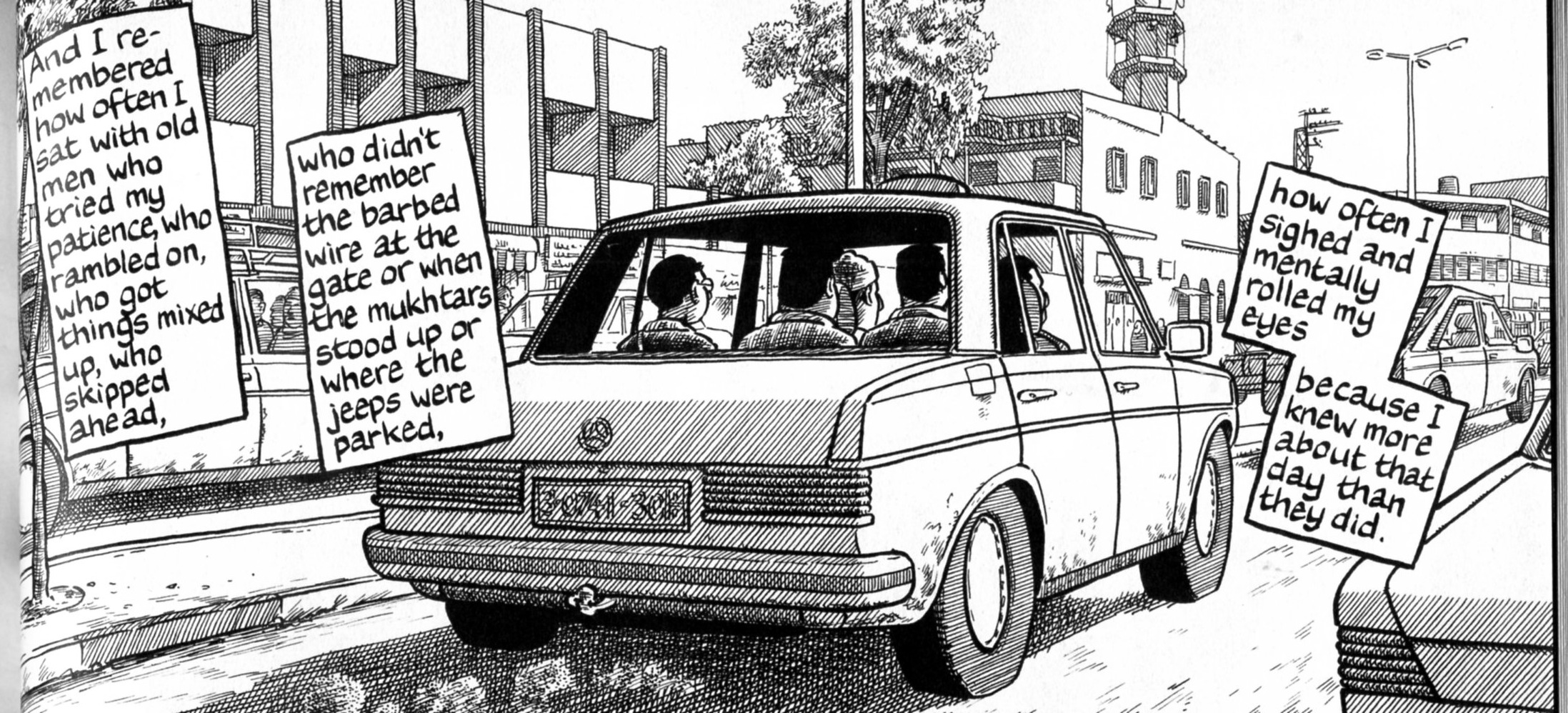

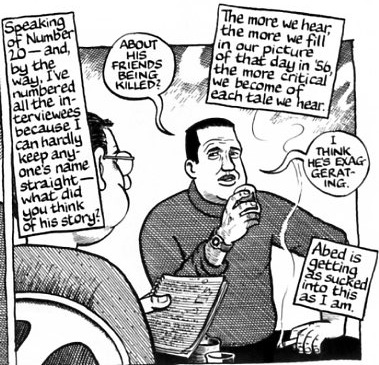

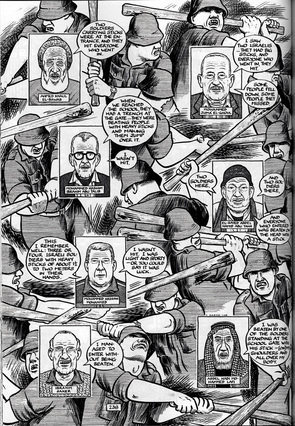

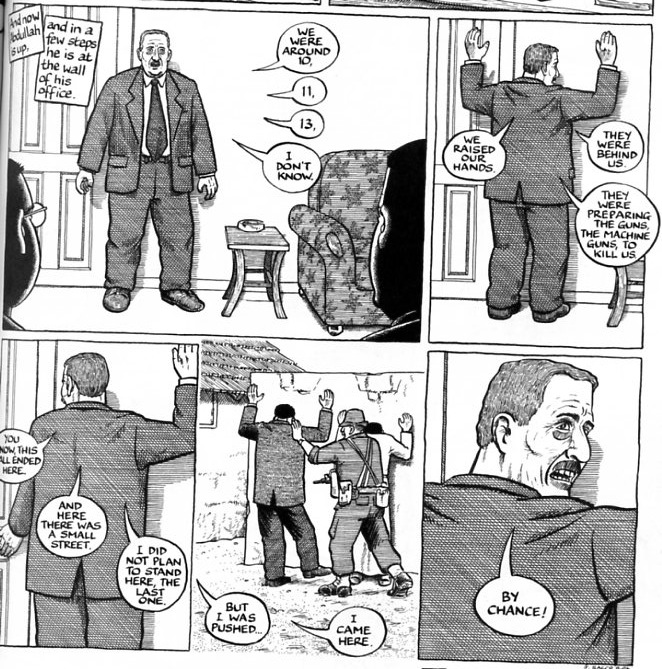

Sacco’s preface (“A Manifesto Anyone?”) clearly articulates the selling point of his comics: the personal touch; the tabletalk; the stray details which betray the messy art of journalism; the fulsome embrace of subjectivity. All these and more present themselves as essential parts of Sacco’s journalistic toolset; his art singling out telling moments in the course of an interview away from the oppressive and quieting glare of a video camera, adding to the stark description of mere prose.

Even so, the comics form presents a number of problems for would be cartoon journalists quite apart from their labor intensiveness and lengthy gestation periods. One of these problems is highlighted by Sacco in his preface:

“Aren’t drawings by their very nature subjective? The answer to this last question is yes…Drawings are interpretive even when they are slavish renditions of photographs, which are generally perceived to capture a real moment literally. But there is nothing literal about a drawing.”

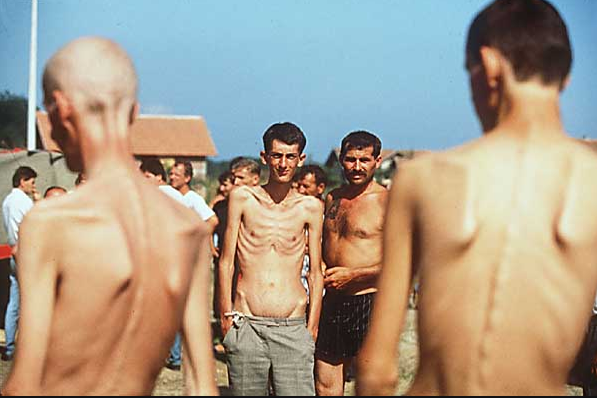

One might say that journalistic drawings inhabit that (un)happy land between the reader’s imagination (in pure prose) and concrete reality (in photography). The former can never be countermanded while the latter—a potent source of “easy” empathy—is beholden to Cartier Bresson’s Decisive Moment.

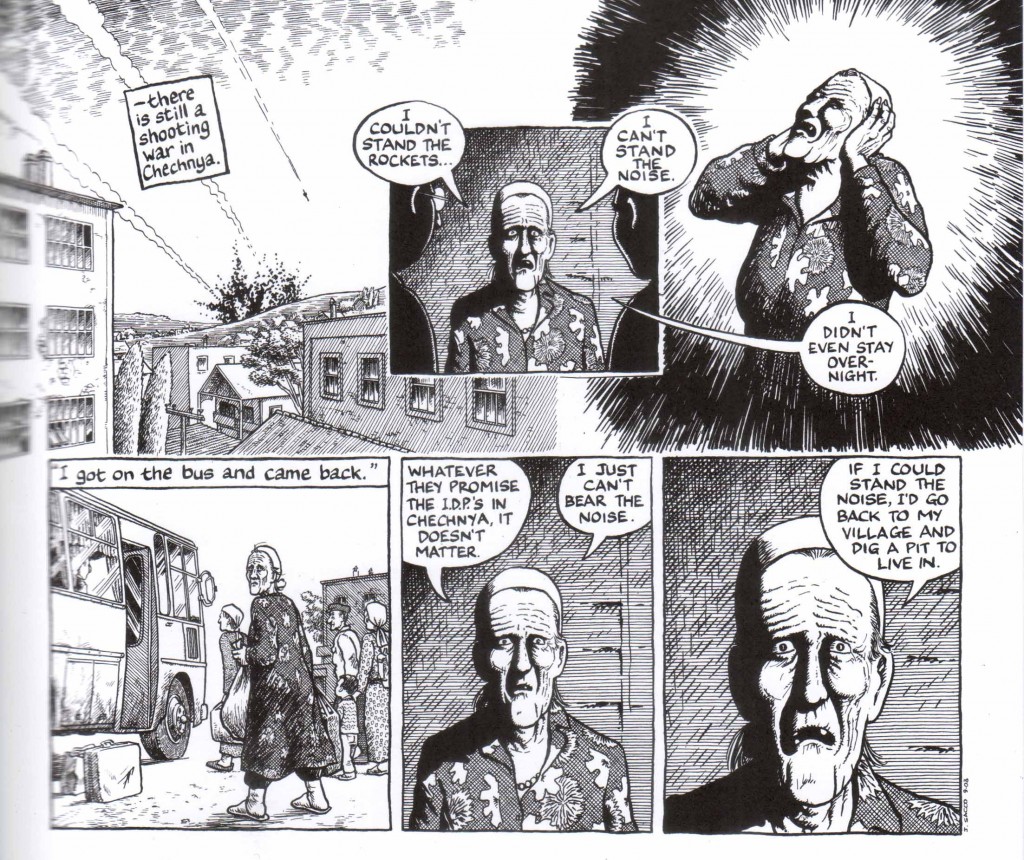

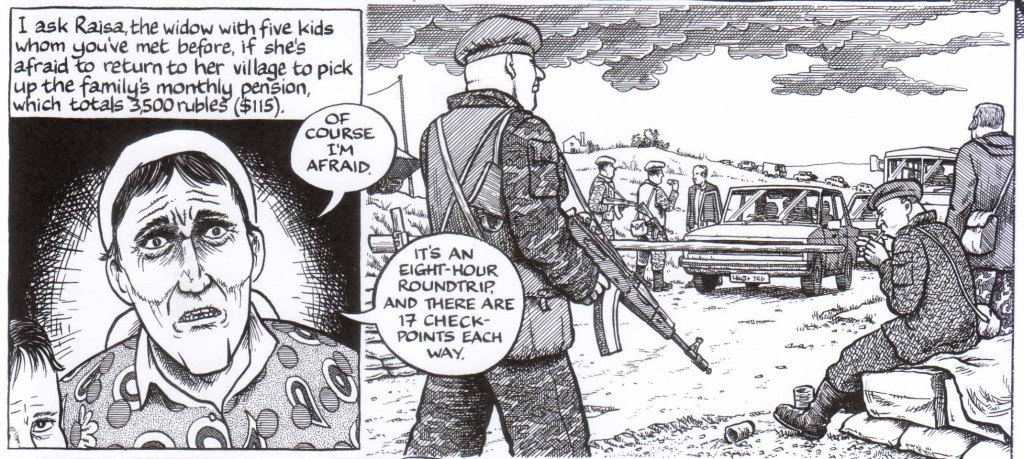

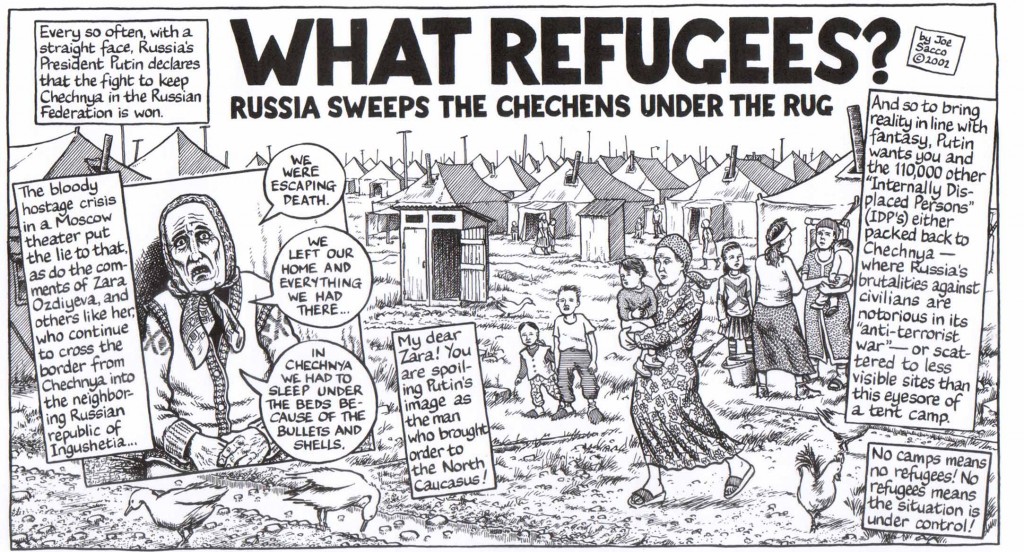

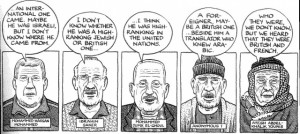

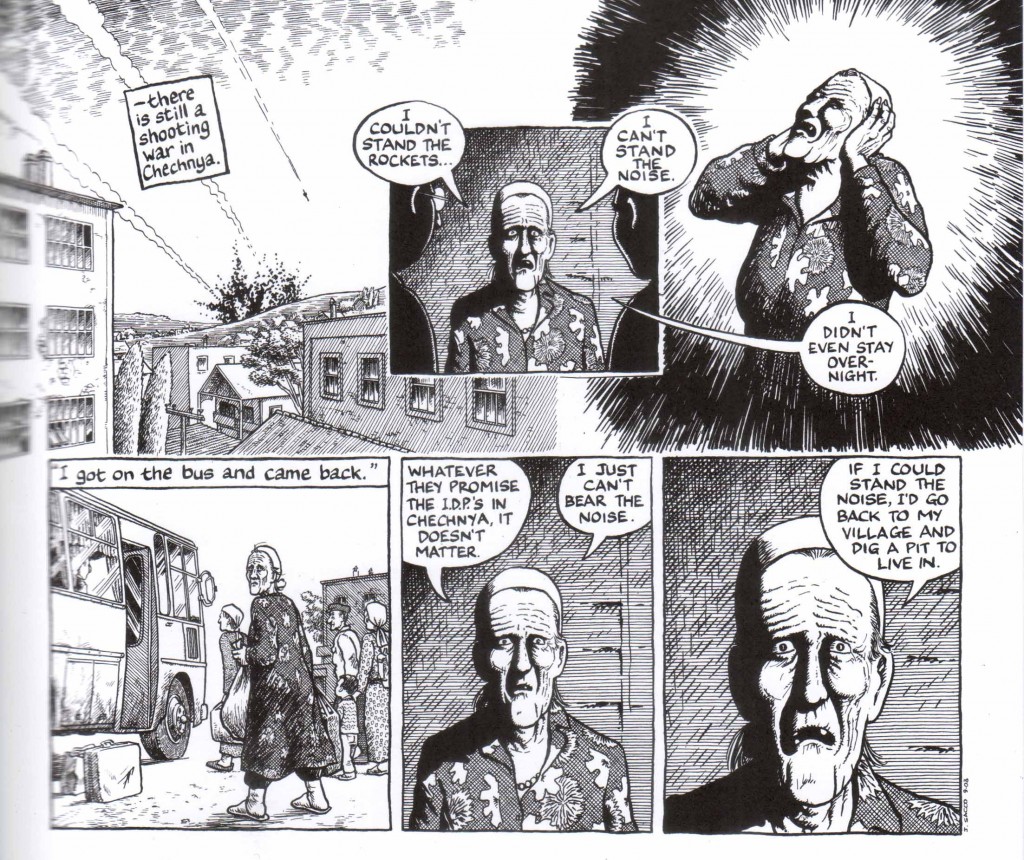

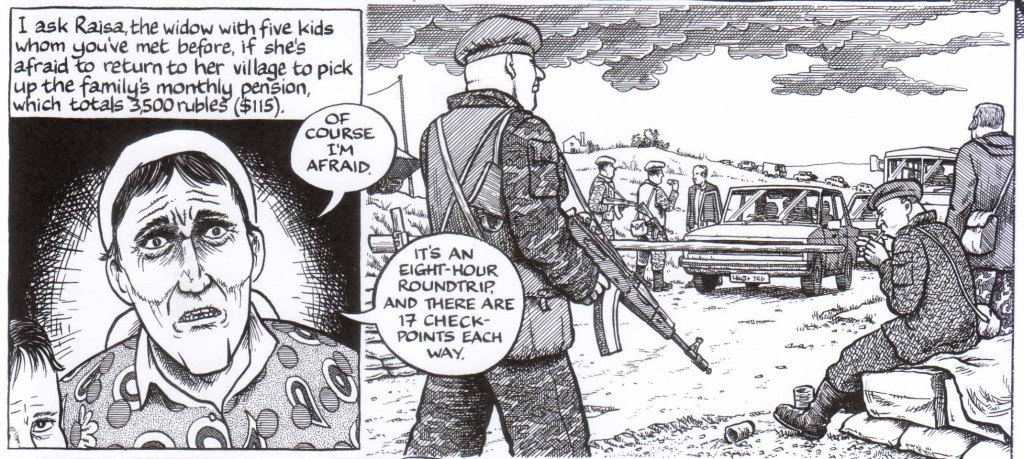

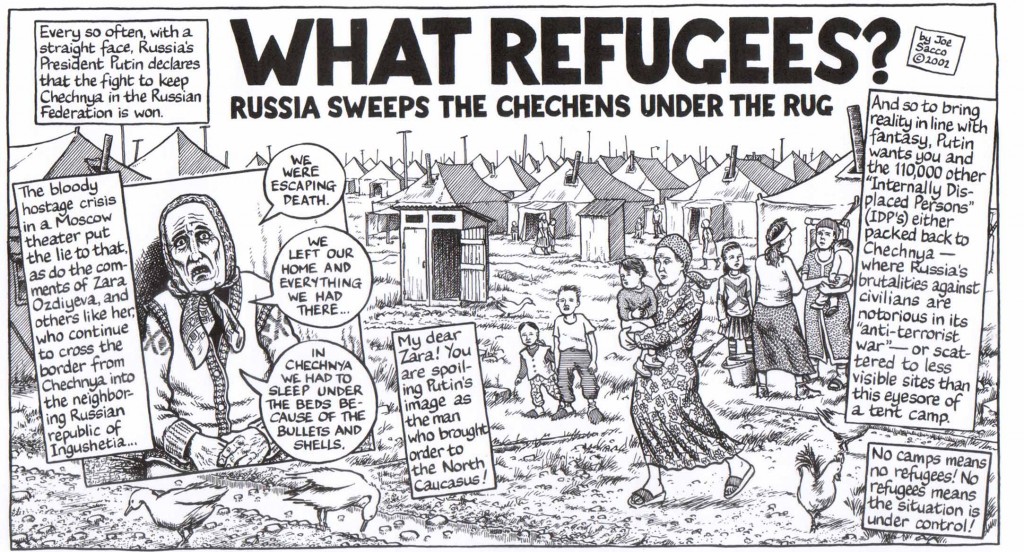

With comics, the abilities of the artist are paramount, and here far more than in most other cartooning genres. While the emotions in Sacco’s stories are communicated with skill and the faces of his characters reasonably distinct, they are still removed from the direct human connection of photo portraiture. What is often lost in translation is that sense of connection to reality and someone real, an affinity which cannot be adequately conveyed through his stylized cartooning which in the early days broached on caricature. Sacco compensates for this with various forms of artifice. Thus Zura and Raisa (from “Chechen War, Chechen Women”) though separated by 30 pages seem almost indistinguishable, the artist reinforcing that element of despair and the commonality in their suffering by means of repetition.

That same tortured face is seen again on page 70 of the collection and a story about Chechen refugees. It is up to the reader to decide if this represents the artist’s persistence of vision or the limitations of his style.

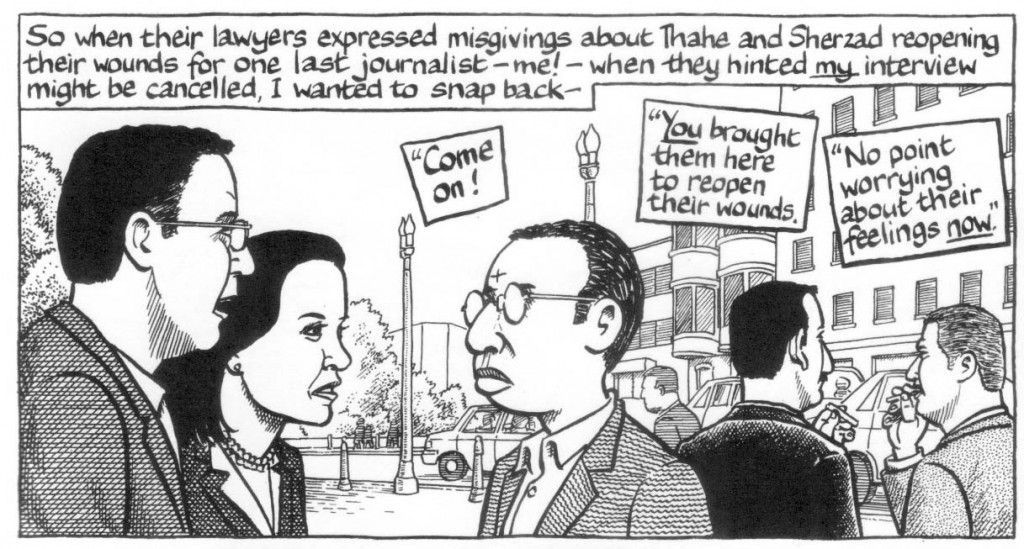

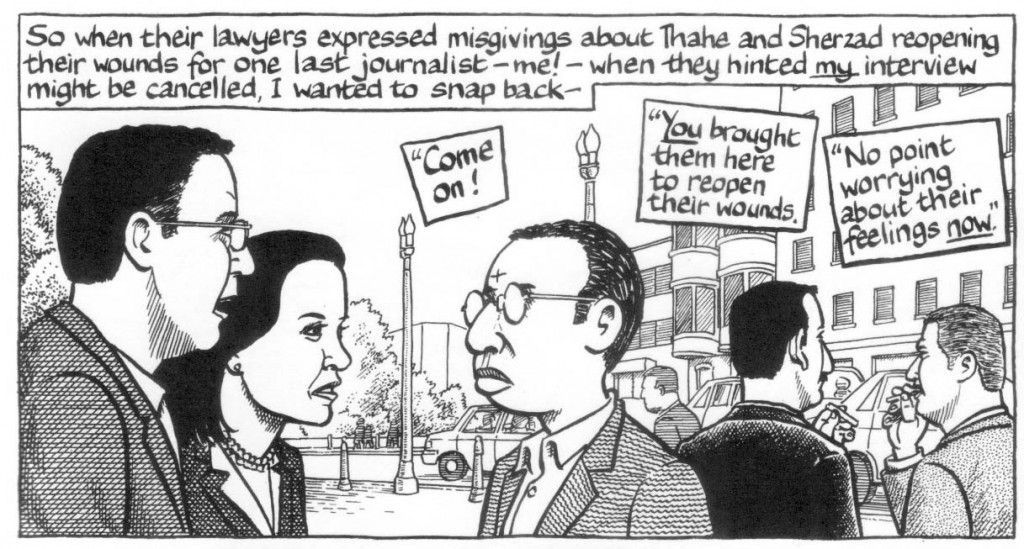

Sacco is of course nothing if not self-critical, these feelings frequently manifesting themselves in the form of self-derision. In Journalism, Sacco can be seen prodding his mercenary journalistic instincts—that cultivated ambition which must surely be a part, however small, of every reporter’s motivation and which just as surely must be quashed in those who have any level of conscience. In “Trauma on Loan”, we find Sacco champing at the bit when he is almost denied an interview with two victims of torture:

“You brought them here to reopen their wounds. No point worrying about their feelings now.”

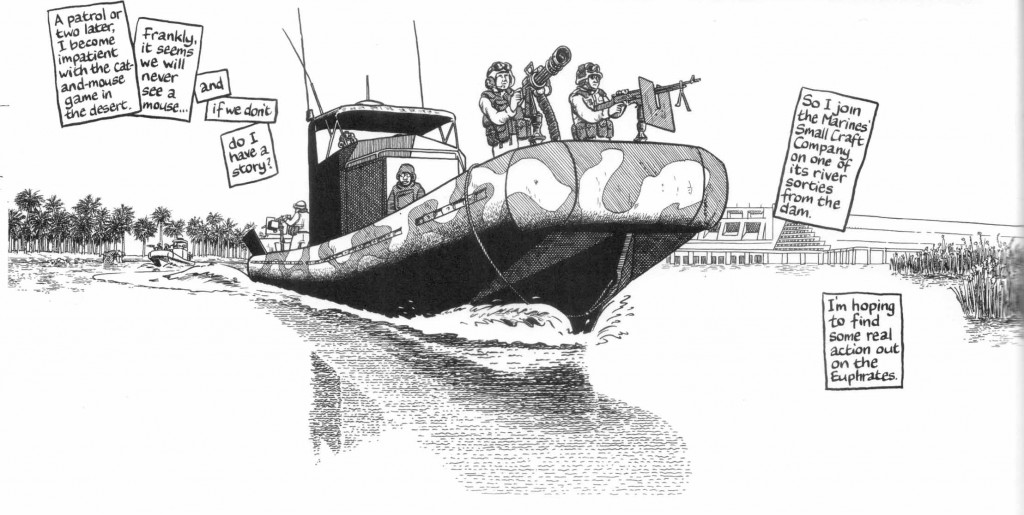

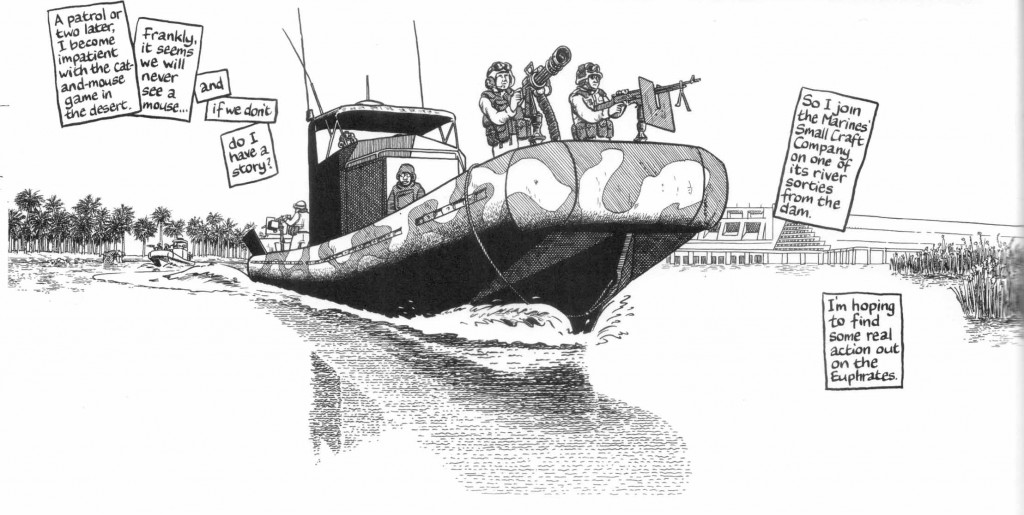

At other times, it is simply a case of a journalist’s bread and butter, the search for some “real action” to spice up a story. The kind of story which most soldiers want to avoid.

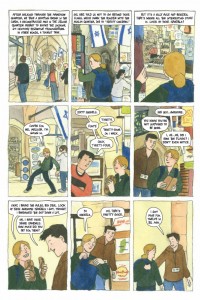

He is similarly unerring in pointing out his weakest stories. In this case, he singles out “Hebron: A Look Inside” (2001) which he describes as his “least successful piece of comics journalism.”

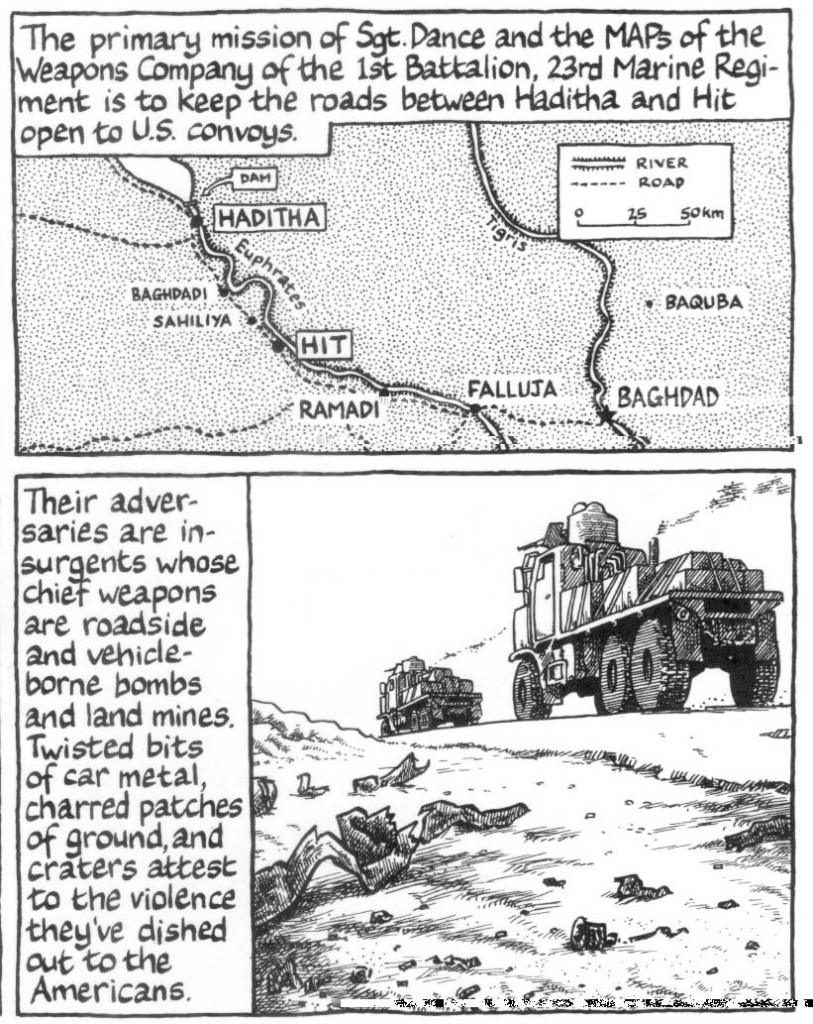

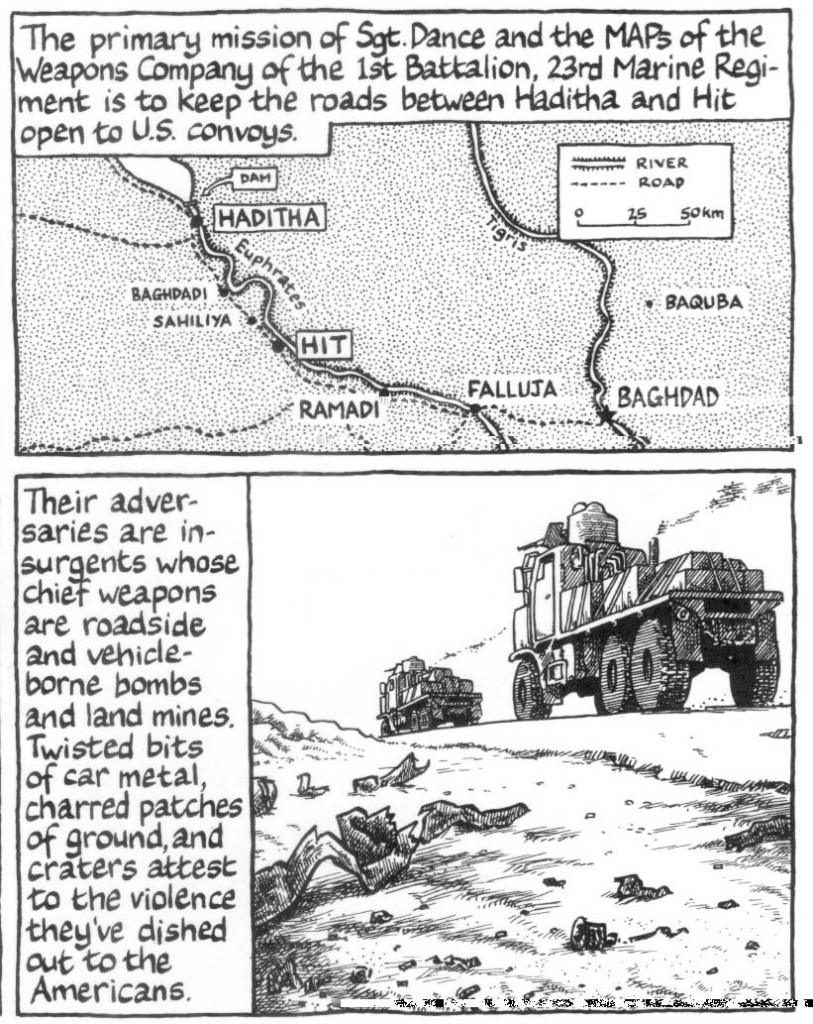

While Sacco’s tropes will be familiar to long time readers, his comics on Iraq do seem somewhat distinctive within the context of his oeuvre. Not because they are unquestionably the best stories in this anthology. Far from it—that accolade might be better directed at his deeply felt portraits of the most wretched peoples of this earth (his encounter with some Dalits in “Kushinagar” for example). The author is also quite right when he suggests that the first story in his Iraq triptych (“Complacency Kills”) doesn’t “[add] anything new to the immense literature of ‘men at war’.” That story does, however, stand out because of its novelty in tone: the journalist now no longer mining the same vein he’s been chipping at since the days of Palestine; no longer fleshing out the sympathetic and distorted faces filled with hunger and despair; no longer solemnly depicting the genocidaires and unremitting faces of evil but here presenting a more genial portrait of the brutalization of his fellow Americans assigned the task of patrolling the highway between Haditha and Hit.

The philosophical conflicts of these fighting men are put on display, their essential humanity conveyed, and their deaths filled with a sadness which is never maudlin. All this perhaps a side effect of embedded journalism—strangely forgiving of the tormentors but still finding a kind of balance in the middle of the rest of this collection. Sacco is patently opposed to the war, yet he gently skirts the immense futility of the soldiers’ deaths. The reader never gets that sense of waste littered throughout Tardi’s comics on the Great War; all that incipient fury held in check by the dictates of reportage which, in this instance, eschews the imagination (the piece was first published in The Guardian) and the even greater suffering of the resident non-combatants—the shadowy figures traversing the highways patrolled by the American forces.

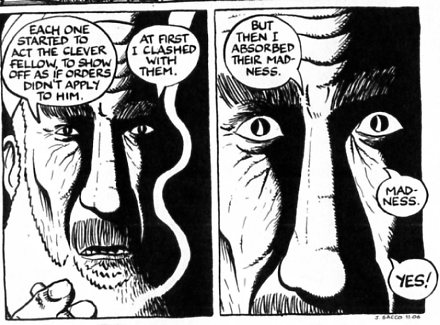

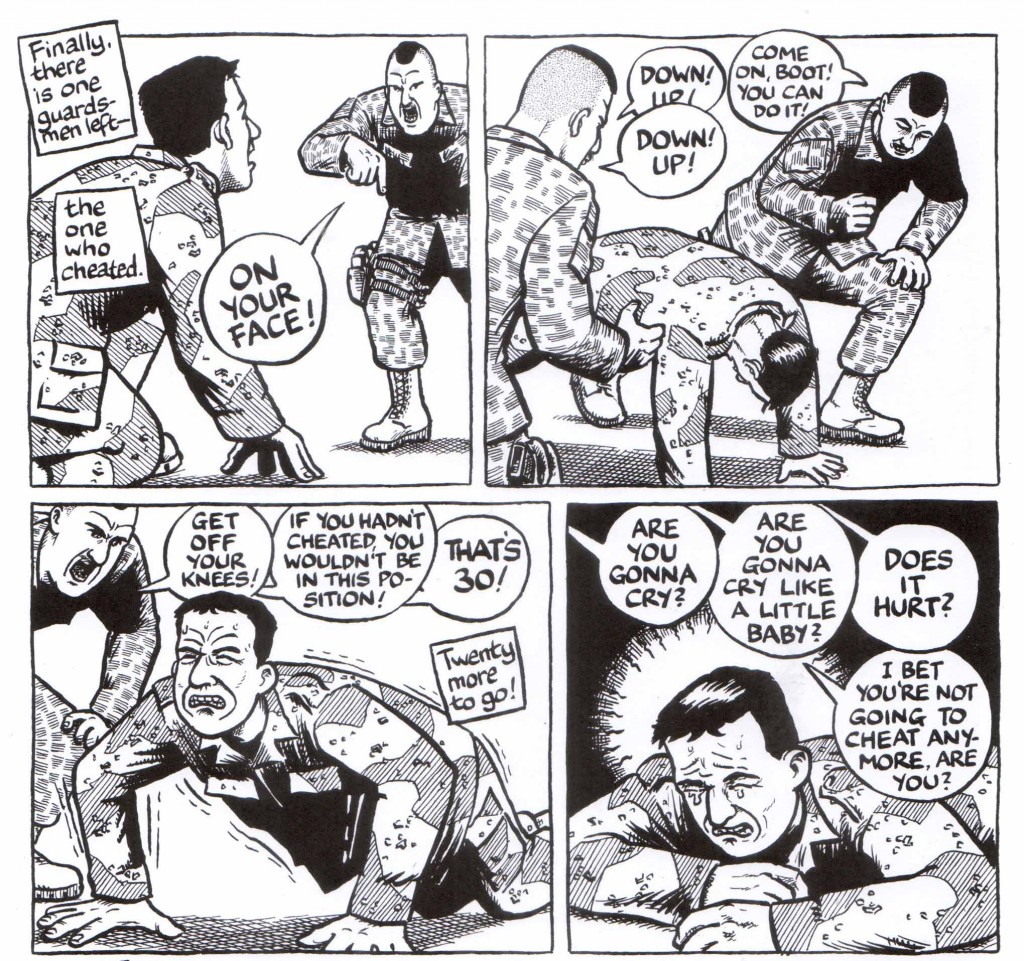

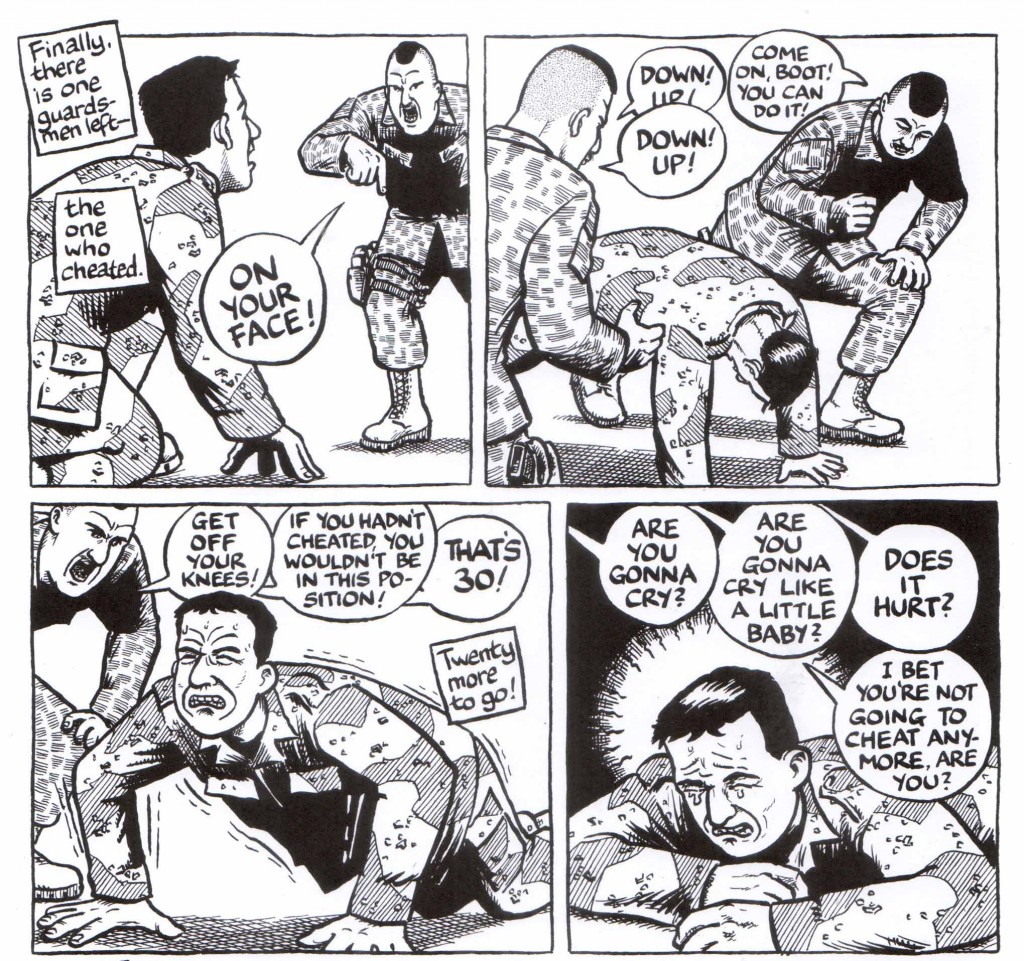

These anonymous figures get names in the story that follows (“Down! Up!”). While aesthetically less impressive, this piece does suggests that Sacco’s skills are best demonstrated not by his stories of the tortured and maimed but by more mundane subjects. This is an extended piece on trainees attached to the Iraqi National Guard (ING) and their interaction with their liberator-colonizers; the captors and their captives secreted away to some mysterious training destination; the actors playing at master and slave in the comics equivalent of a confined space of undescribed backgrounds; the plot bending the knee to the dictates of human interaction, the faces of every individual contorted into extremes.

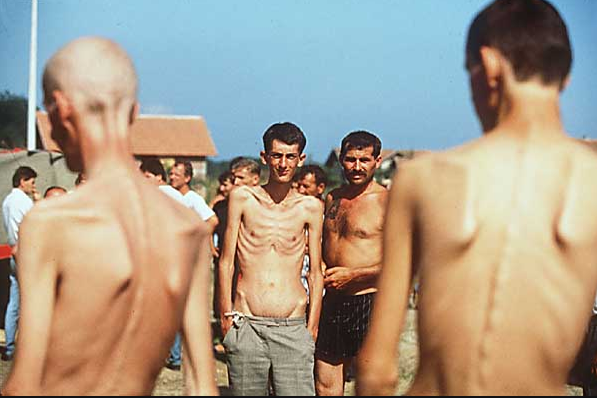

So much passion on display and yet, Sacco is clearly wrong in suggesting that it is the comics medium which hasn’t allowed him “make a virtue of dispassion.” This may be the case on a personal basis (and perhaps that is all he means) but it seems excessive to shower blessings on the “inherently interpretive medium” of comics. The truth is that comics are quite capable of conveying facts with dispassion as evidenced by the vast majority of comics non-fiction. Just like authors who cast their words firmly in the direction of human cost stories, it is Sacco’s personal proclivities (and not any comics essentialism) which is responsible for the shape and tone of his comics. The decisions in comics journalism are perhaps more obvious than those in video or photography, yet it should be clear from controversies like those surrounding the depictions of Bosnian Serb concentration camps that even photo journalism is also open to interpretation and partisanship.

“Another trap promoted in American journalism schools is the slavish adherence to “balance.” …Balance should not be an excuse for laziness. If there are two or more versions of events, a journalist needs to explore and consider each claim, but ultimately the journalist must get to the bottom of a contested account independently of those making the claims. As much as journalism is about “what they said they saw,” it is about “what I saw for myself.” The journalist must strive to find out what is going on and tell it, not neuter the truth in the name of equal time.” – Joe Sacco (from his preface)

Similarly, Sacco’s disavowal of “balance” seems overstated if not a deliberate misunderstanding. The pursuit of balance has little to do with not taking sides, coming down in the middle, or pissing off both sides as he caricatures in his preface. Rather it suggests a dedication to teasing out the intricacies of any given situation and recognizing the limitations in human understanding. His advocacy of the journalism of “what I saw myself” obscures the essential mystery of “truth.”

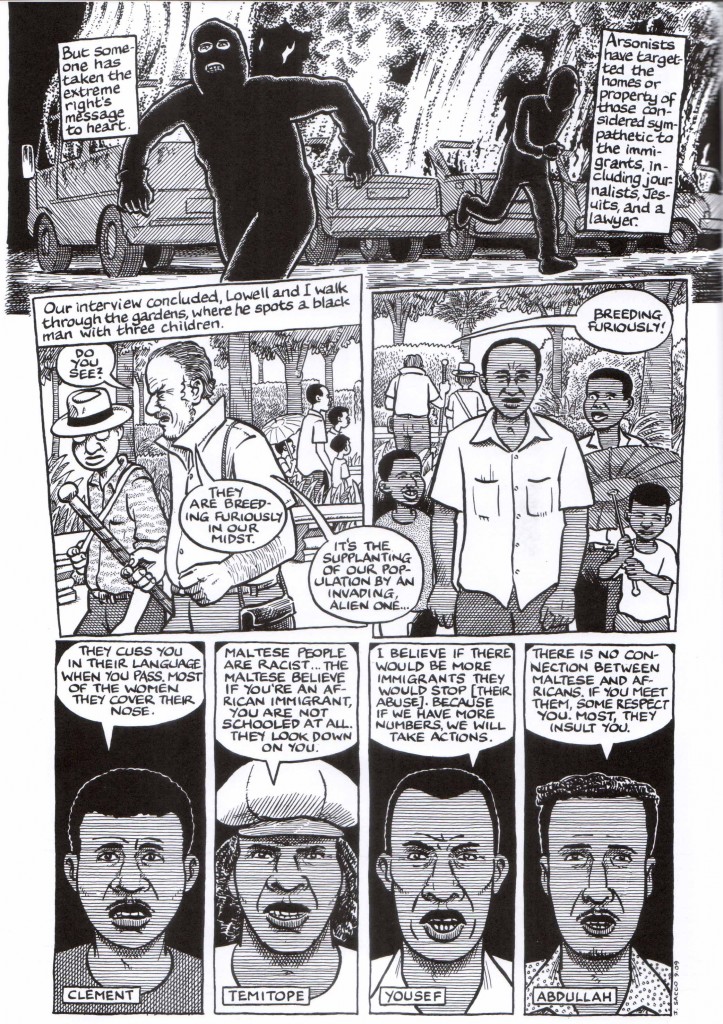

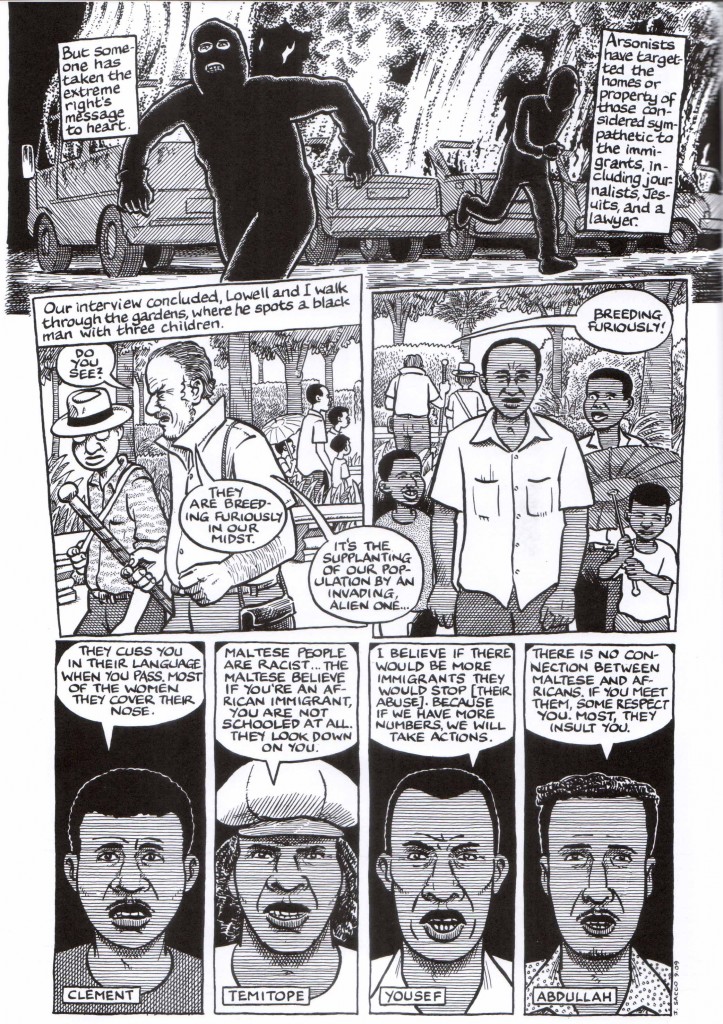

The clarity and concerted purpose of Sacco’s work often elides the complexities of each flashpoint he visits—the very reasons for the insolubility of their problems. Only in “The Unwanted”, his report on the Maltese-African immigration problem, do we get some sense of this intractability. While Sacco’s sympathies lie firmly with the political refugees, he describes keenly the Maltese sardine can of fear, economic hopelessness, and easy racism. The predicament presents itself as a microcosm of the problems faced by Europe as a whole.

In this sense, his extended examination of the African migrant issue can be seen as “balanced” (an insult in Sacco’s book), allowing us to apprehend the dilemmas while preserving his consistent sympathy for the downtrodden

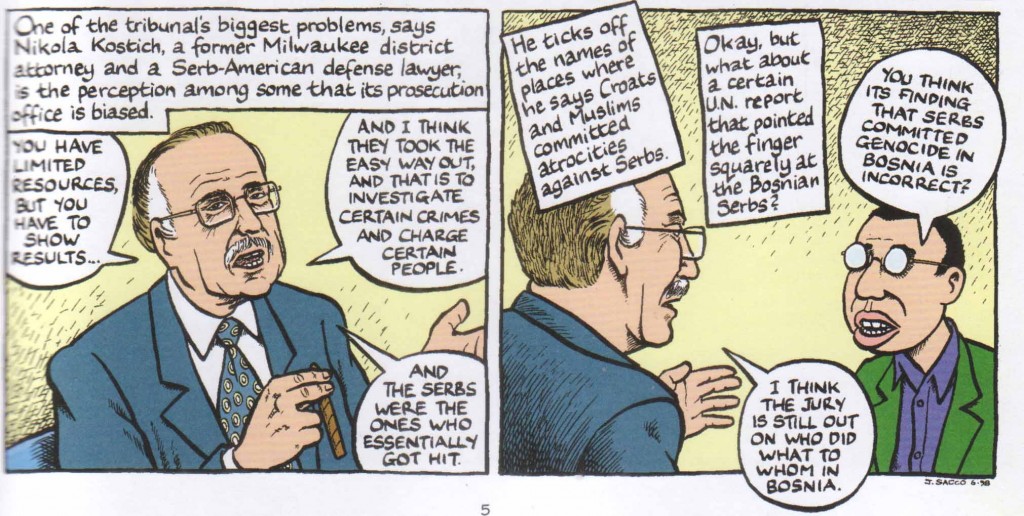

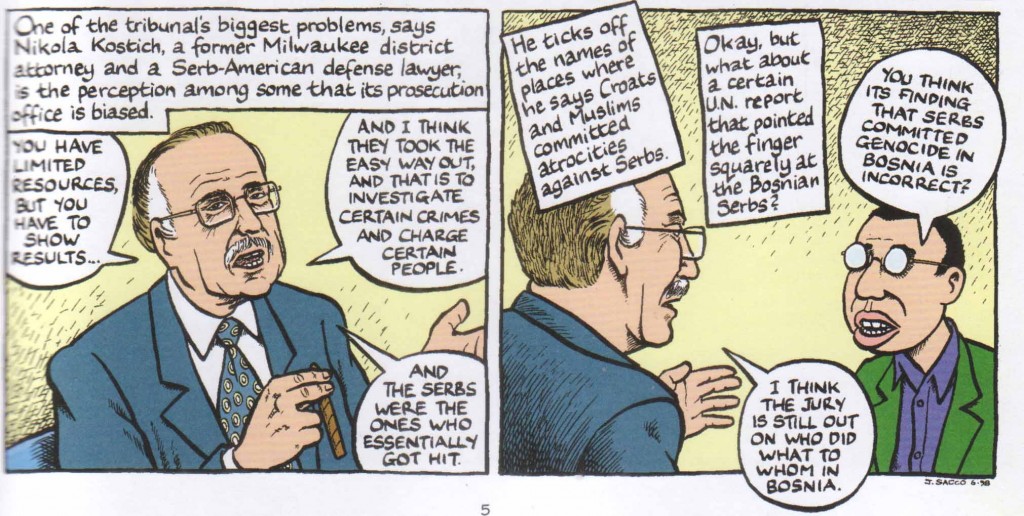

Not so the familiar and lengthy reportage on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the former Yugoslavia. The stories from these war zones present us with an almost Manichean world of the oppressed and oppressors, a long tradition in comics as it happens. A mild-mannered challenge in the Hague by a Serb-American defense attorney fizzles out pretty quickly. The Israelis are represented by a recalcitrant Zionist in “Hebron: A Look Inside.” The powerful, as Sacco puts it, “are excellently served by the mainstream media or propaganda organs.”

“I don’t feel it is incumbent on me to balance their voices with the well-crafted apologetics of the powerful.”

A perfectly sensible view which only leaves the reader the task of deciding which side is the more powerful and which has the greater voice in the mainstream media.

Without any furrowing of the narrative, genuine understanding can hardly be realized. Where one approach might convince us of the righteousness of our aid, our charity, and perhaps our armed intervention, the alternative might give us reasonable pause to consider our moral reflexivity. The former approach lulls us into complacency, the latter challenges all received ideas and sympathies. Sacco’s frequent advocacy of an unwavering crystallized truth suggests that he is not primarily a journalist and reporter but a political activist; one who has consumed the facts, the scholarship, and the primary sources and sees himself as an evangelist, giving voice to those who have none and presenting himself and his works as one of several rallying points in the journalistic sphere.

Hence his protestations against journalistic “balance”, the practice of which must seem hollow and self-serving in the face of taking sides and championing the needy. This is a noble endeavor but like all messages from the pulpit, one that must be tested thoroughly before acted upon. And if we agree with Sacco when he holds to Robert Fisk’s adage that “reporters should be neutral and unbiased on the side of those who suffer”, we should first consider being “neutral and unbiased” on the side of tangled truth.

* * *

Further Reading

(1) Kathleen Dunn’s review at The Oregonian. This article contains a lot of basic background information on Sacco.

(2) David Ulin’s review at the LA Times.

“The rap on Sacco, of course, is that he is less a journalist than an advocate, who in such works as “Palestine” and “Footnotes in Gaza” blurs the line between observer and activist. That’s true, I suppose, in the narrowest sense, but it’s also reductive, and with “Journalism,” he convincingly refutes the argument.

Sacco is rigorous about telling both sides of the story, developing sympathy for the American soldiers even as he questions their presence in Iraq. The key is his attention to the human drama, which blows open in the final frames of the story, where he describes the fate of a river unit with whom he’d gone on patrol.”