The 2015 bombardment of superhero films is over. It was a relatively light year, just Avengers 2, Ant-Man, and the franchise-flopping Fantastic Four. But Warner Bros. and Marvel Entertainment have twenty superhero films in various states of production, all of them due in theaters by 2020.

Back in 1978 superheroes were so rare in Hollywood, the first Superman included the subtitle The Movie. So you may think of costumed do-gooders as relatively recent invaders of the silver screen, but they leaped to theaters long before landing in comics. 2016 promises Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice, Captain America 3, and X-Men: Apocalypse, but 1916 saw three rounds too.

In Arthur Stringer’s The Iron Claw, Creighton Hale plays “an easy going idiot” working as a millionaire’s personal secretary by day, but at night he dons the guise of the mysterious Laughing Mask. By the end, he’s wooed his boss’s daughter and thwarted the nefarious Iron Claw.

Francis Ford joined Hale as the similarly clad Sphinx in The Purple Mask, only this time the masked hero has a masked anti-heroine to woo too, Grace Cunard’s lady thief and so-called Queen of the Apaches, the first celluloid superheroine. She leaves her purple mask as a calling card.

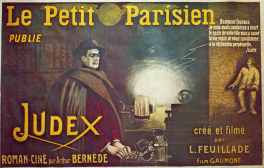

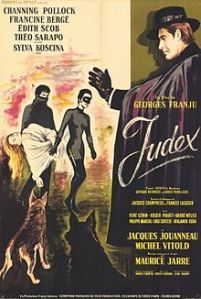

But the first most influential superhero film award goes to Louis Feuillade’ Judex—a partial reversal of The Iron Claw since Judex begins as a vengeance-seeking blackmailer disguised as a personal secretary before falling for his boss’s daughter. I like to show my class the original unmasking scene, Yvette Andréyor creeping into the hero’s batcave of a bedroom and discovering his make-up kit. Nowhere nearly as dramatic as the Phantom of the Opera unmasking, but shot a decade earlier.

My favorite superhero silent film, the 1927 classic The Russian Affair, won Best Picture in 2011.

That’s because it exists only in the opening sequence of director Michel Hazanavicius’ The Artist. But the invented film shows how popular masked heroes were in the early 20th century. The Russian Affair—as well as glimpses of its equally pretend sequel, The German Affair—features the fictional silent star George Valentin in tuxedo, top hat, and domino mask—the quintessential costume of the pre-comic book superhero. Raffles, Tarzan, Robin Hood, Night Wind, Gray Seal, Lone Wolf, they all transformed themselves into silent superheroes, most unheard now. Except for Zorro, which The Artist inserts into Valentin’s fictional filmography, replacing the very real Douglas Fairbanks.

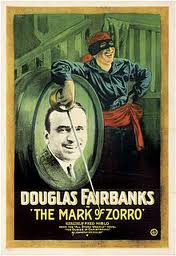

Judex had barely exited American theaters before Fairbanks was skimming issues of All-Story for his own pulp hero to adapt. A year later, the Judex-inspired Zorro was an international icon. Hazanavicius even reshoots the best action sequence, dressing The Artist’s Jean Dujardin in Fairbanks’ Zorro wardrobe. The Mark of Zorro didn’t win Best Picture in 1920 only because the Academy Awards didn’t exist for another decade.

The 1928 Alias Jimmie Valentine was going to be a silent adaptation of O. Henry’s gentleman thief tale, but MGM called the stars back to record the studio’s first talkie instead. Fairbanks’s 1929 Three Musketeers sequel included his spoken prologue, but his talking Taming of the Shrew flopped later that year, as did his final Private Life of Don Juan. Hazanavicius’s gives his alter ego a tap-dancing afterlife, a superpower not in Fairbanks’ repertoire, so the real Fairbanks was replaced by a new breed of action heroes, some of them actual supermen.

Olympic swimmer Johnny Weissmuller took his last gold medal in 1928, Buster Crabbe in 1932. Both went on to play Tarzan. I watched Weissmuller on my aunts’ TV, one of those crate-sized machines that flickered as the cathode ray tubes heated. I’m thankful my aunts didn’t keep the battle scenes I doodled on scrap paper, all those blowdart-blowing savages gunned down by white hunters. All Hollywood sandpits, I surmised, were seven feet deep, designed to swallow everything but a victim’s groping fingers.

MGM did the same to Fairbanks and every other ex-star unable to adapt.Not that the superhero sound era was an easy transition for Hollywood either. MGM only started their talking Tarzan franchise because they had the footage.

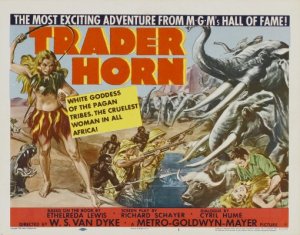

Trader Horn, the first big budget film shot on location, was a disaster. The production team returned from Africa with scene after scene of inaudible dialogue, a star infected with malaria, and the suitcases of crew members devoured by crocodiles and trampled by rhinos. They also had miles of jungle footage, way more than could ever fit into a single movie. Trader Horn came and went in 1931, but to capitalize on all that location shooting they’d already paid for, MGM rolled out Tarzan the Ape Man the following year. It was a cheap hit that spawned five low-budget sequels that returned Burroughs’ superman to the pop culture spotlight.

After Christopher Reeve retired his cape following 1987’s catastrophic Superman IV, Tim Burton rebounded with Batman, but otherwise the 90s are a 1930s reboot. Warren Beatty in Dick Tracy. Billy Zane in The Phantom. Alec Baldwin in The Shadow. It’s hard to remember a time when the Marvel pantheon wasn’t pounding box offices, but Hollywood once preferred retro-heroes. Disney’s The Rocketeer sported 30s curves, even though the character debuted in comics in 1982. That’s why Jim Carey threw on a yellow zoot suit along with the 1987 The Mask comic book. When Sam Raimi of later Spider-Man fame couldn’t get the rights to the Shadow, he cast Liam Neeson as a modern master-of-disguise instead. Darkman isn’t any good, but it does show how much comic book superheroes were a mutation of their pulp predecessors, an evolutionary process repeated in film.

It took a couple of decades, but the double flop of Seth Rogen’s 2011 The Green Hornet and Disney’s 2013 Lone Ranger and Tonto may have finally closed the theater doors on the 1930s. According to that math, are Warner Bros. and Marvel Entertainment being over optimistic with their 2020 projections? If the 30s are finally over, how long can DC’s early 40s and Marvel’s early 60s continue to last?