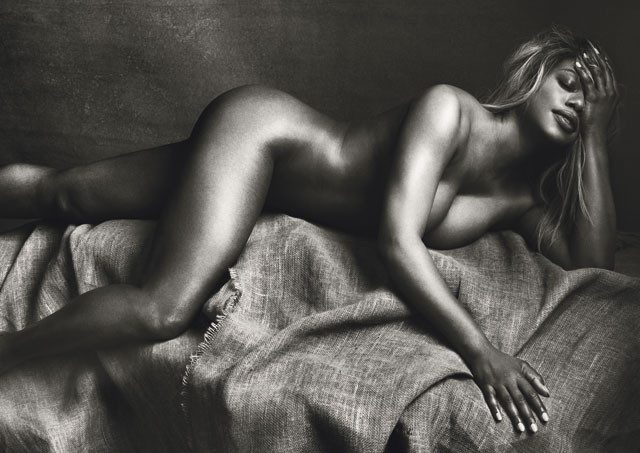

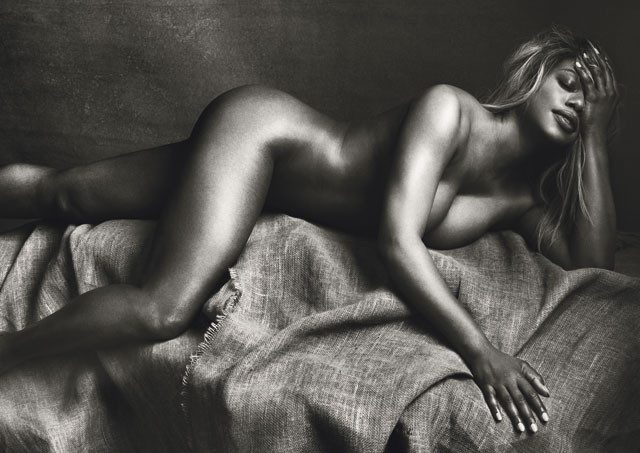

Last week I wrote a piece about Laverne Cox’s nude photoshoot for Allure and how various feminisms have often failed black women and trans women. The piece was in particular a response to a post by Meghan Murphy in which she criticized Cox in what I argued were transphobic, racist, and cruel terms.

For my essay I conducted several interviews — but as often happens, I was only able to use little bits of them. The interviews were all really thoughtful and enlightening, though, and it seemed a shame to waste them. So I asked folks if it would be okay to reprint them here, and everyone (including Playboy) kindly agreed. All the interviews are below, from shortest to longest responses, more or less. My questions are in italics; answers are of course by the interviewees.

_______

P. Marie is a former sex worker; she blogs a mix of trash, nail art, and selfies at pmariejust.tumblr.com and @_peech on twitter.

Why has feminism and radical feminism had trouble respecting black women?

As far as I can see, the problem can be boiled down to (among many things) entitlement and a sense of ownership. For decades, white feminism has said things like “being a voice for the voiceless” – essentially taking ownership of the voices (and bodies) of Black women, sex workers, and Transgender people through exclusion and subscribing to violent, racist, and transphobic rhetoric.

While at points in history, speaking up to protect others was necessary and desired by us from them, it’s now turned into a clear case of overbearing entitlement and greed for the spotlight. Opportunistic hatred is published quickly and easily by both news houses and blogs with large followings, giving bigoted white feminists a platform to share their trash with a digital megaphone.

The shame in all this is how difficult it seems for feminists as a community to see this happening as often as it does.

With dangerous ideas like “women born women”, the new emergence of the “rescue industry”, and anti sex work and anti black feminists these newest waves of feminism are going on the offensive and becoming more harmful by the day. The problem blooms larger when the actuality of “being the voice for the voiceless” is comprised solely of ignoring people who are willing to speak for themselves. Feminism isn’t helping anyone anymore – unless helping yourself to take the stage by way of abusing women you don’t like counts, and I don’t think it should.

Could you talk just briefly as a black woman and a sex worker what your reaction to the Laverne Cox photos are? Is it empowering or satisfying to see black women recognized as beautiful in that way? Do you see sexualized images of black women as a problem at all, or does it depend on agency/the situation?

As for my reaction to Laverne’s pictures, I feel a sense of happiness for her. She’s done interviews and spoken about her self esteem/appearance, and to see her be able to have those photos done and (very obviously) look and feel so beautiful, what a happy moment. It helps me as an individual when I see any Black woman feeling beautiful and sharing that with the world – reminding people we ARE beautiful, desirable, feminine, and strong – which is exactly, thankfully, what Laverne Cox has done for us.

When it comes to sexualized images of us, for me it’s all about agency! Did we consent? Are we respected? Is this our choice? Is this a collection of body parts or erased humanity? There are a lot of questions that run through my mind at that intersection of sex work and being a Black woman.

What Laverne Cox did put a smile on many faces and some hope in a lot of hearts. I think there are very few better things a person could do in life.

__________

Zoe Samudzi is a researcher and activist; she’s a project assistant at UCSF. You can follow her on twitter, @ztsamudzi.

Could you talk just briefly about how some strains of radical feminism have marginalized black women and trans women? Like, specifically, why does feminism have trouble embracing those groups? Are the reasons linked?

It isn’t just radical feminism, but also mainstream White Feminism that has targeted and excluded women of color, sex workers, trans women, and others marginalized identities. But these radical second wave feminisms emerged in reaction to traditional femininity, a part of which is female sexuality, which they characterized as “slavery to patriarchy.” These radical feminisms, in my opinion, don’t even feign inclusivity: there’s a very prescriptive understanding of what emancipation and liberation looks like and in the rejection of femininity, it fails to recognize women’s agency (including sexual agency). Couple this misogynistic demonization of femininity with the general devaluing of certain bodies and identities – black women, trans women, and sex workers most notably – and you have shaming, commentaries about “self-objectification” (actually the imposition of the male gaze) when women pose nude, refusal to recognise sex workers as agents, and so on. This exclusion and marginalisation links to white female entitlement and the refusal to de-center whiteness. White women have historically been perpetrators of violence against black women’s bodies, and the same entitlement and identity-centerdness in feminism has enabled them to proclaim themselves as the arbiters of womanhood. It’s also worth nothing that it isn’t just radical feminism that has marginalized trans women and sex workers: that has and does happen in black feminism/womanism, as well.

Do you see fashion images of black women as disempowering? empowering? Some mix of both? Do black women have a different relationship to objectification/sexualization than white women do?

I guess I don’t pay them much attention, but the models are gorgeous. Beyond being empowering or disempowering, I see fashion images of black women as promoting similar discouraging messages about body images as white ones. But black women lend an element of “cool” and afford a cultural capital to fashion that white models to not (they’re always thrown in there for some performance of athleticism or exoticism). The objectification of black women is both gendered and racialized: there’s not only a gendered sexualization, but also a fetishization as an exotic radicalised “other.”

I know you don’t identify as a feminist right now…I guess I wondered what feminism would have to do to get you back? What needs to change before you’d feel comfortable identifying as a feminist again?

I don’t think I’ll ever identify as a feminist again, though there’s a tremendous amount of scholarship in marginal feminisms (i.e. from sex workers, in transfeminism, from migrant/immigrant women, from disabled women, from women in the Global South, and so on). I’m not spending any more energy trying to convince white women that my identity is worthy: I’d rather invest my energy in gender politics grounded in intersectional understandings, as womanism is.

________

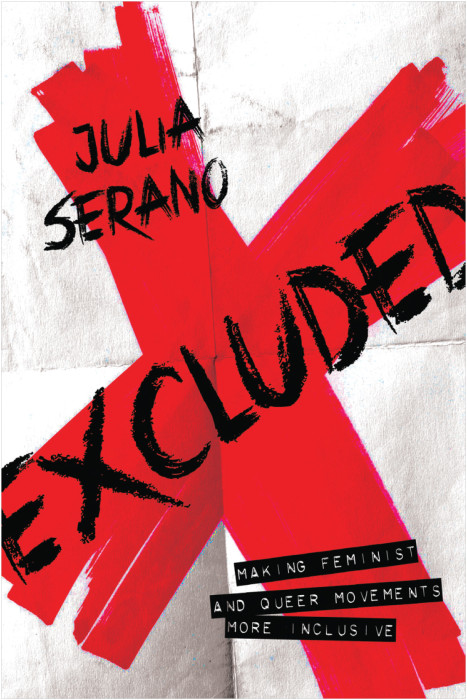

Julia Serano is a trans feminist and author. Her most recent book is Excluded: Making Feminist and Queer Movements More Inclusive.

Why has feminism been so resistant to including trans women?

There was a time when most feminists (like society at large) were very resistant toward trans women, largely because of misconceptions that people in general had about us. But with increasing trans awareness over the last ten or twenty years, most strands of feminism now acknowledge (and sometimes ally with) trans people and issues. One major exception has been trans-exclusive radical feminists (often called TERFs).

While they may differ to some degree in their perspectives, most TERFs subscribe to a single-issue view of sexism, where men are the oppressors and women are the oppressed, end of story. This rigidly binary view of sexism erases transgender perspectives. It leads TERFs to view trans men as “dupes” or “traitors” who have bought into patriarchy’s insistence that being a man is superior to being a woman. This framing also leads them to depict trans women as entitled men who are “infiltrating” women’s spaces and “parodying” women’s oppression, or as “gender-confused” or androgynous people who transition to female in some hapless attempt to “assimilate” into the gender binary. Which is so bizarre that they think that, because no one in the straight mainstream views out trans women as being well-respected legitimate gendered citizens!

Is that linked to, or how is it linked to, feminism’s discussions of objectification, or with its discomfort with sex workers/sexualized portrayals of women?

Yes. Their single-issue view of sexism (i.e., men are the oppressors and women are the oppressed, end of story) ignores intersectionality—the fact that there are many forms of sexism and marginalization that exacerbate one another, and that people who experience multiple forms of marginalization may view sexism (and feminist responses to sexism) very differently.

Some feminists (including many trans-exclusionary ones) forward the following overly simplistic argument: In patriarchy, men sexualize and objectify women, therefore women should avoid being sexualized and objectified, because it is inherently disempowering and anti-feminist. This seems to be the case that Meghan Murphy is making. But it ignores the fact that all women are not seen and interpreted the same in the eyes of society. If you happen to be a disabled woman, or a woman of color, or a queer or trans woman, or a sex worker, then you are also constantly receiving messages that you are *not* considered desirable or loveable according to society’s norms.

Feminists have long discussed the “virgin/whore” double-bind: If we express our sexualities and/or expose our bodies, many people will sexualize and objectify us. But if we repress our sexualities and hide our bodies, that also has negative ramifications, especially for those of us who are deemed to be non-normative or undesirable for some reason or another.

I completely understand why, in a world that constantly attempts to erase and eradicate trans women of color, Laverne Cox might feel that that photo-shoot might be empowering for her and for other trans women who share similar identities, backgrounds, or circumstances. This does not by any means imply that they are “buying into the system”—rather, it most likely means that they are navigating their own way through society’s mixed messages (e.g., women are seen as sexual objects, but at the same time, trans women and women of color are viewed as sexually deviant, undesirable, or sexual abominations).

Laverne Cox is an outspoken feminist who has been raising public awareness about sexism and multiple forms of marginalization for several years now. Given that history, Murphy’s response seemed especially condescending to me. It is okay for feminists to disagree. But when you accuse someone who is creating positive change in so many ways of “reinforcing” sexism (especially when they face obstacles that you do not have to face), then you should probably consider whether you are the one who is “holding back the movement” by excluding women who differ in their experiences from you.