Florida Burial created by Julian C. Chambliss

I recently participated in a public arts project that focused on the burial of the Confederate Flag. Predictably, this event generated controversy as the media reduced it to “black guy burns a confederate flag.” However, the goal was to engage the public about the Confederate Flag’s contested history. Conceived by artist John Sims, The Confederate Flag – 13 Flag Funerals grew from over a decade of artistic work. However, while art inspired this event, there is an argument to be made that the Confederate Flag is a “history” problem. This is a problem created by a “southern version” of history that ignores historical fact in favor of regional myths.

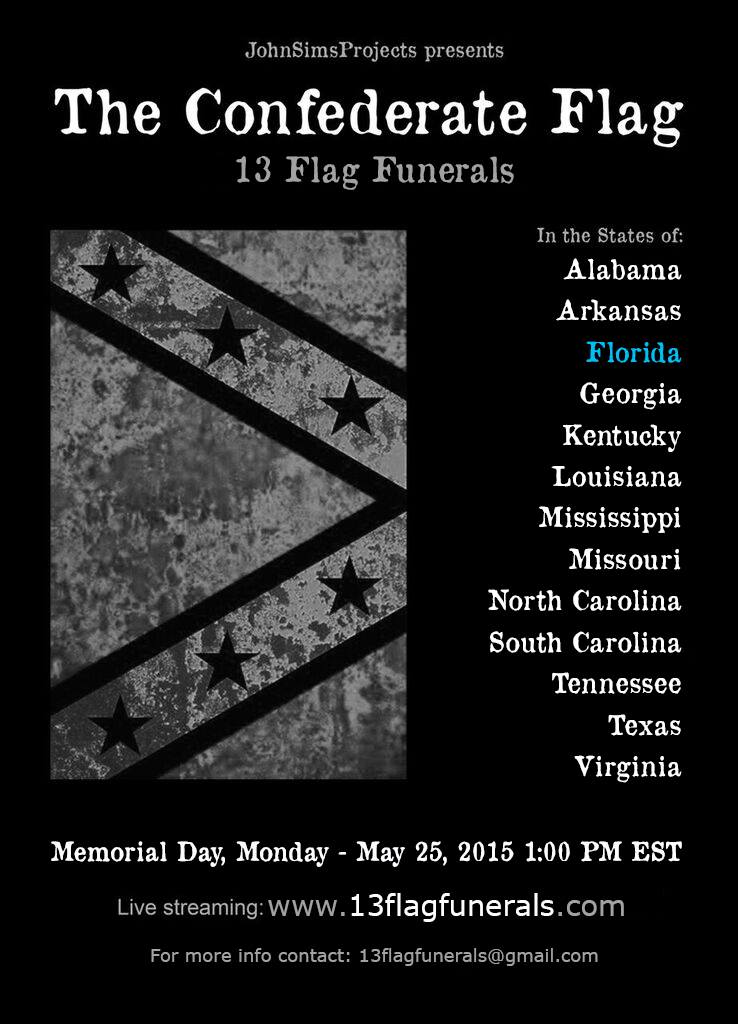

13 Flag Funerals by John Sims

The 150th anniversary of the Civil War and the contemporary race debates in the United States provided the backdrop for this coordinated multi-state public art event. A burial inverts the assumptions of memorial and reverence linked to the southern experience defined exclusively by rebel fighting against the union; the project emphasized coming to terms with the Confederacy’s end. It suggests we can seek closure by recognizing the repressive and regressive ideas that defined that slave society and look to put southern experience on a different path. I agreed to organize a funeral because recent and past events in Florida highlight the disputed legacy of southern history. If Americans interrogate the flag’s meaning, they might reassess its role in an illusory public memory constructed to steal African-American liberty and stifle dissent after the Civil War.

Julian Chambliss, Associate Professor of History at Rollins College (left), Jeff Grzelak, Civil War historian (center) debate the burning and burial of the Confederate flag. Photo by Lance Turner

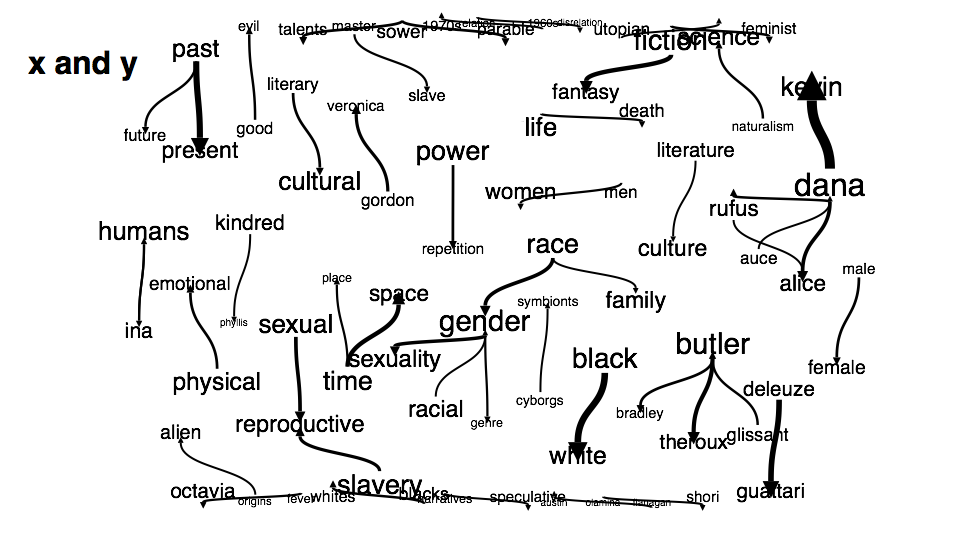

A union victory and Reconstruction could not stop the rise of a powerful “Lost Cause” mythology that distorted meaning and actions connected to the Civil War.1 Historian David Blight wrote of Frederick Douglass’ understanding of historical memory that Douglass realized that memory “was not merely an entity altered by the passage of time; it was the prize in a struggle between rival versions of the past, a question of will, power, and persuasion. The historical memory of any transforming or controversial event emerges from cultural and political competition, from the choice to confront the past and to debate and manipulate its meaning.”<.2 Douglass saw the years after Reconstruction dominated by false memories that bonded whites in the North and South to the detriment of African Americans.

It was a deliberate process. As one southern veteran explained, if southerners could not justify the war they would, “go down in History solely as brave, impulsive but rash people who attempted in an illegal manner to overthrow the Union of our Country.”.3 The result of their efforts coalesced around broad themes we know well today. You can “hear” them whenever we see the Confederate Flag. When people say, “The Civil War isn’t about slavery” or when they venerate the Confederate soldier, that is part of a broad cultural resistance rooted in a specific way of remembering the past. This imagined history shaped facts and marshaled emotion to support southern efforts to reassert control through force. The obvious targets of this persecution were African Americans, but in truth this unequal social landscape injured the poor of every color. Journalist T. Thomas Fortune explained in his 1884 book, Black and White: Land, Labor, and Politics in the South, the oppression of blacks was just one part of a broader “pauperization” of the southern labor class that benefitted southern elites..4

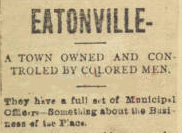

Winter Park Scrapbook, Olin Library Archive and Special Collection, Rollins College.

These actions continued an established pattern in the South. Before the war southerners altered their rhetoric about slavery as required to bolster perceptions of the slave system. With slavery gone, white southerners created a new story to support their control over African Americans. Through archival research projects, my students and I have seen how both white and black southerners fought against this mythology.

Eatonville, the first incorporated black town in the U.S., came into existence as a way to repudiate the white assertions that “the colored people had no executive ability about them, and would ruin rather than build up.”.5 African Americans in Florida were threatened or killed for attempting to be fully engaged citizens. If they joined unions, voted, owned property, and failed to show deference they faced punishment..6 Whites that dared to speak against this treatment faced stigmatization, threats, and violence. By the turn of the century, a “separate but equal” segregation rooted in African American social, political, and economic subjugation was firmly established.

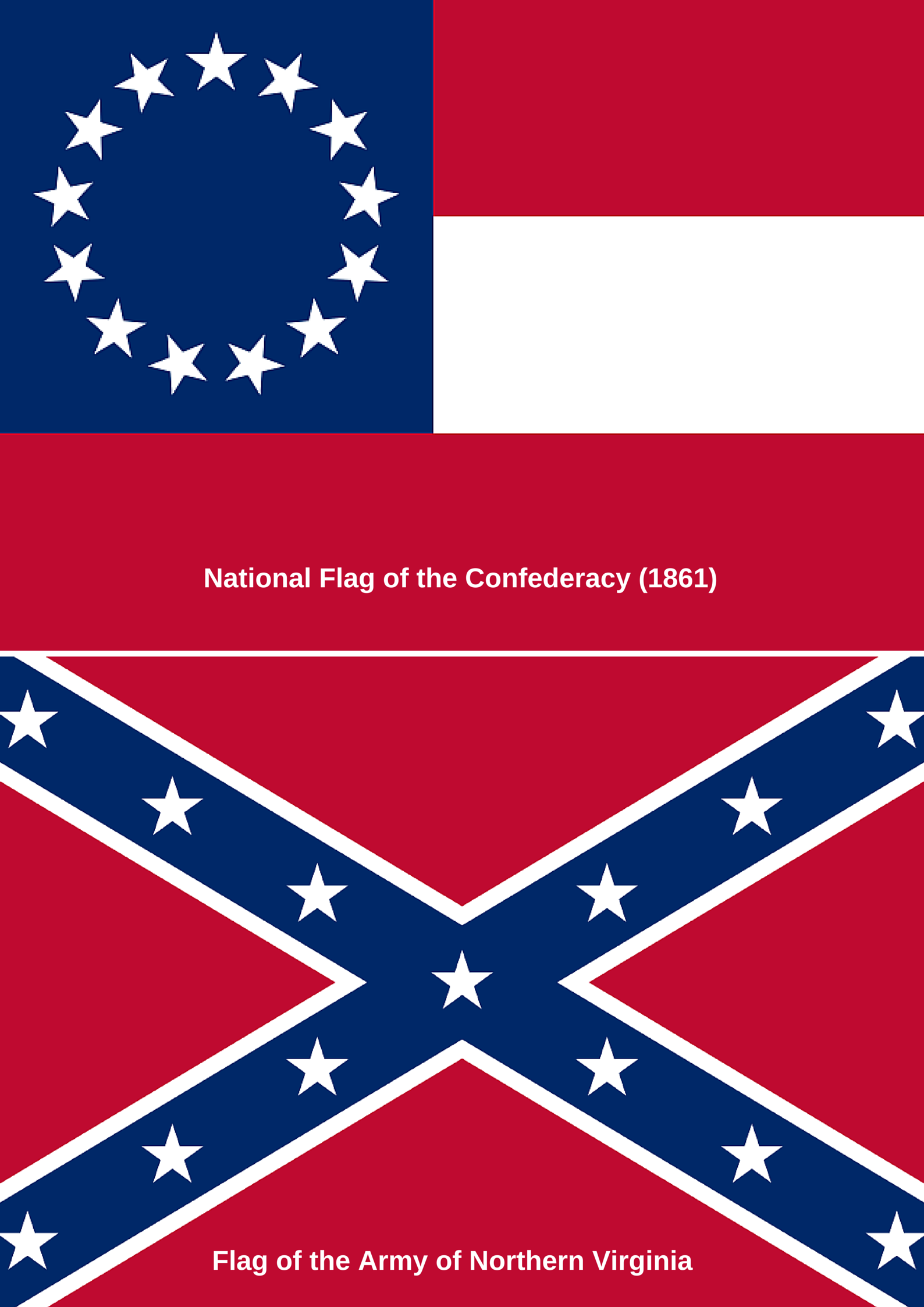

Flags Confederacy by Julian C. Chambliss

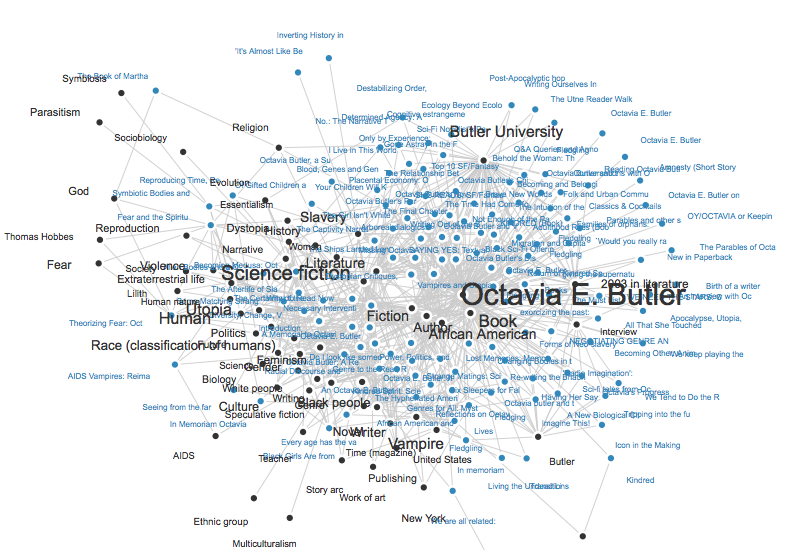

This legacy of race conflict is the public narrative we must understand when we judge the flag. An online search for the “Confederate Flag” in most contemporary search engines will return one image above all others. Designed by William Porcher Miles, this flag is not the national flag of the Confederacy. Indeed, it was rejected in 1861 in favor of a “Stars and Bars” design that was ultimately unpopular. .7 The flag we know was incorporated into the battle flag for the Army of Northern Virginia. Robert E. Lee’s army was so successful on the battlefield this flag was integrated into subsequent national flags..8 As the southern narrative of the “Lost Cause” shaped southern views, the flag was infused with meaning beyond historical fact..9

While the initial “Lost Cause” narrative had elements of mutual valor as a focal point of public discourse, such sentiments shifted after the turn of the century as a new generation of southerners rejected the “criminal” effect of northern actions after the war..10 Historian William A. Dunning inflammatory condemnation of Reconstruction gave southern actions and perspectives a justification rooted in a twisted history. As Alan D. Harper explained, “It was ‘Dunning thesis’ above everything else, that produced for us the popular stereotype of Reconstruction, a stereotype whose central figure are in the words of Horace Mann Bond, ‘the shiftless poor white scalawags; the greedy carpetbaggers; the ignorant, deluded, sometimes vicious Negroes; and the noble, courageous and chivalrous Southerners who fought and won the battle for White Supremacy’.”.11

The Popular South by Julian C. Chambliss

Popular culture embellished myths and justified violence in the first decades of the twentieth century. The success of D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation (1915) based on Thomas Dixon’s 1905 novel The Clansman: An Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) sparked a resurgence of the secret society created to resist Reconstruction. While the original KKK was effectively neutralized in the 1870s, the success of Griffith’s film inspired William J. Simmons, an Atlanta based recruiter for fraternal societies, to establish a new organization..12

The resurgent KKK’s slogan was 100% Americanism and it appealed to white Protestant men (and their families). This organization expanded throughout the 1920s bundling white supremacy, anti-immigrant, anti-Semitism and anti-Catholicism feelings into a potent mix that attracted a national membership. The group’s success allowed KKK members to be elected to political office in southern states. Perhaps more astonishingly, states such as Indiana and Colorado also elected KKK members to municipal and state offices..13 Internal conflicts, scandals, and public opposition led to the KKK’s decline in the 1930s, but the public’s romance with southern culture reached new levels with the release of Gone with the Wind in 1939. Based on the novel by Margaret Mitchell, the southern experience presented in this film encapsulated the tropes of the Lost Cause for broad consumption.

The myth and reality of southern life clashed after WWII with the rise of the Civil Rights Movement in the United States. The Supreme Court’s Oliver Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas (1954) decision ended the separate and unequal doctrine created by southerners in the 1890s. In response, segregationist groups resisted calls for civil rights reform and adopted the Confederate Flag as a symbol of their commitment to preventing integration. While contemporary defenders of the flag are quick to accuse segregationists of “stealing” the flag and assigning it racist meaning, the reality is that this approbation aligned with southern cultural practice of refuting reform that began decades before. Protesters turned to the flag because they understood it to embody the imagined South conceived and championed after the war. This was a South where whites were supreme and African Americans (and their supporters) were second-class citizens.

After the 1960s’ rights revolutions, the practices associated with segregation were scrubbed from public life. Yet, southerners continue to resist. According to Bruce Schulman a “commercialized” southern whiteness rooted in “driving pickup trucks, listening to country music, watching stock car races and flying Confederate Flag” emerged in the 1970s..14 Detached from any overt racial framing, this cultural narrative was another version of pushback and corresponded with a powerful political transformation. The dissatisfaction and resentment that led southerners to abandon the Democratic Party in the 1960s made them the backbone of conservative Republican political aspirations in the 1970s. By the 1980s the Republican Party relied on southern and suburban voters to support its call for “smaller government” and “traditional” values that critics argued undermined hard fought civil rights gains.

Water burial of the ashes, “The Confederate Flag: A Belated Burial in Florida” Photo by Lance Turner

Since the 1990s we have periodically argued about the Confederate Flag. Yet, because we remain mired in distorted history, the injurious nature of this symbol resting easily in the public sphere is never fully explored. Beyond the heritage excuses, the flag is a signifier of a broader pattern of southern resistance to social reform that started after the Civil War and never stopped. For those shaped by the “Lost Cause” version of history, the flag burial was a challenge to bedrock beliefs.

The threats online and the emails demanding I be fired are nothing compared to the violence faced by previous generations. Indeed, for many people this project will quickly fade. The burial will not matter to people that equate the Confederate Flag to the Quran or the Bible and call the project blasphemous. It will not spark a reflection in those that question my citizenship or education as a black man. However, it might spur others to consider the dissonance of the flag as a defining symbol. For these people, it could inspire new thoughts and perhaps the search for a different marker of their regional identity. If that happens, the effect of the fractured history represented by the flag may start to heal.

__________________

1. Caroline Janney, “The Lost Cause,” Encyclopedia of Virginia, July 9, 2009, http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Lost_Cause_The#start_entry.

1. David W. Blight, “‘For Something beyond the Battlefield’: Frederick Douglass and the Struggle for the Memory of the Civil War,” The Journal of American History 75, no. 4 (March 1, 1989): 1159, doi:10.2307/1908634.

3. David S. Williams, “Lost Cause Religion,” New Georgia Encyclopedia, May 15, 2005, http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/lost-cause-religion.

4. T. Thomas Fortune, “Black and White: Land, Labor, and Politics in the South,” Internet Archive, accessed May 23, 2015, https://archive.org/details/blackandwhitela00fortgoog.

5. Loring Augustus Chase, “‘Eatonville’–Winter Park Scrapbook, 1881-1906.,” Central Florida Memory, April 4, 1891,http://digital.library.ucf.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/CFM/id/27434/rec/22.

6. Paul Ortiz, Emancipation Betrayed: The Hidden History of Black Organizing and White Violence in Florida from Reconstruction to the Bloody Election of 1920, 1st ed. (University of California Press, 2006).

7. Southern Lithograph Co., “Our Heroes and Our Flag,” still image, www.loc.gov, (1896), http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2006677653/.

1. Thomas G. Clemens, “Confederate Battle Flag,” Encyclopedia of Virginia, July 18, 2014, http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Confederate_Battle_Flag#start_entry.

9. Caroline E. Janney, “War over a Shrine of Peace: The Appomattox Peace Monument and Retreat from Reconciliation,” Journal of Southern History 77, no. 1 (February 2011): 93.

10. Ibid., 99.

11. Alan D. Harper, “William A. Dunning: The Historian as Nemesis,” Civil War History 10, no. 1 (1964): 54–55, doi:10.1353/cwh.1964.0042.

13. Shawn Lay, “Ku Klux Klan in the Twentieth Century,” New Georgia Encyclopedia, July 7, 2005, http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/ku-klux-klan-twentieth-century.

14. “When The KKK Ruled Colorado: Not So Long Ago,” Denver Library, June 19, 2013, https://history.denverlibrary.org/news/when-kkk-ruled-colorado-not-so-long-ago.

15. Bruce J Schulman, The Seventies: The Great Shift in American Culture, Society, and Politics (Cambridge, MA.: Da Capo Press, 2002), 106.