This piece first ran on Comixology. I thought I’d reprint it here for Halloween.

_____________________

The most fertile source of horror is reproduction itself. From Alien to The Thing to Shivers to Invasion of the Body Snatchers, ominously splitting eggs and terrifyingly gravid wombs are constantly birthing nightmare, nausea, and unidentifiable glop.

Junji Ito’s Uzumaki uses preganancy as a theme in a number of its stories — most obviously in the two parter “Mosquitoes” and “Umbiliical Cord” where near-term women suck the blood of the living to satiate their unnatural fetuses. Still, the series’ most disturbing chapter is probably “The Snail” — a story which is equally, if more elliptically, obsessed with reproduction.

“The Snail” is the story of Katayama, a boy who oddly only shows up to school when it is raining, and even then only shows up late. Over time, Katayama moves slower and slower and gets damper and damper, and his fellow students notice that a spiral mark has formed on his back. Spirals are always really bad news in Uzumaki (which in English means “spiral”) and soon enough Katayama is crawing painfully and wetly down the evolutionary scale.

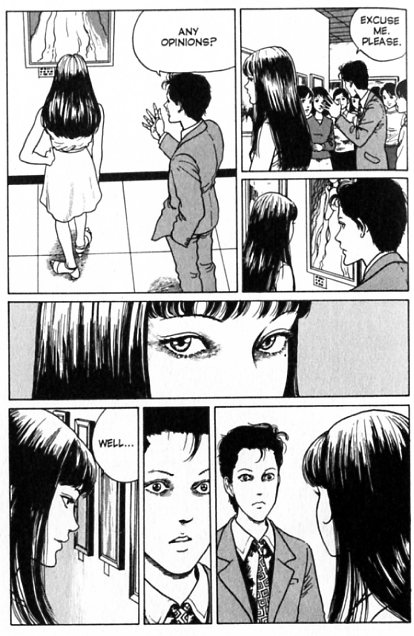

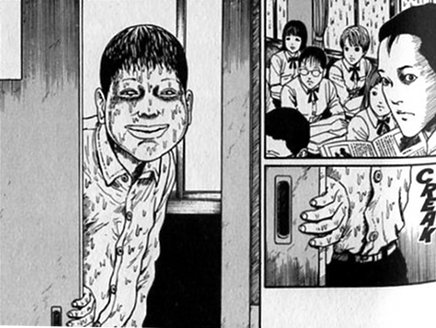

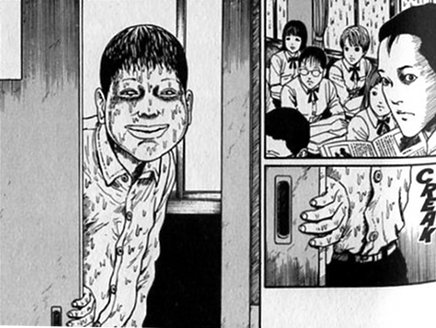

So…all of that is no doubt unpleasant, but where’s the sex-and-pregnancy I promised you? Well, here’s Katayama’s first entrance into the classroom:

His appearance here is certainly supposed to be repulsive…but part of why it’s unsettling is that it’s not-all-that-subtly sexual. Katayama’s most prominent feature is his large, full-lipped disturbingly suggestive mouth. And, of course, he’s covered in a nameless fluid, that seems significantly more viscous than rainwater. In addition, the way the scene is blocked, with the startled classroom faces slack in anticipation as Katayama comes through the narrow door, has the frozen claustrophobic intimacy of a primal scene.

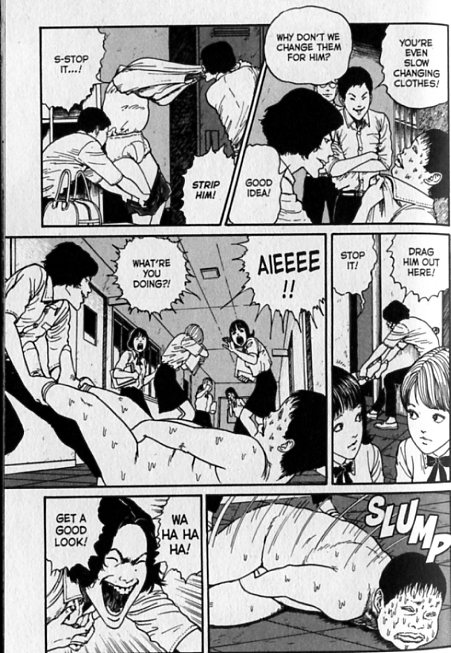

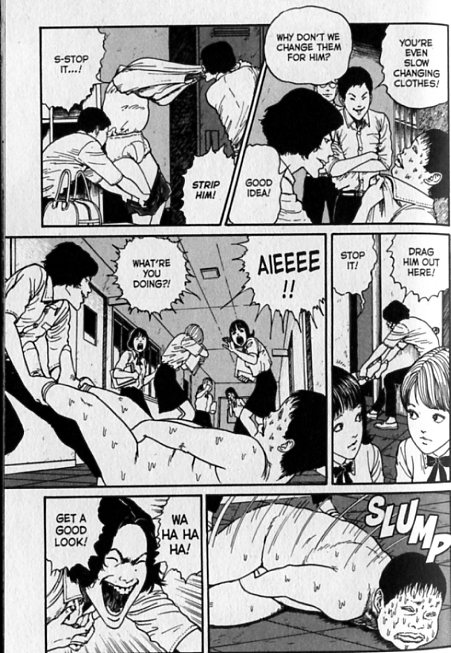

Katayama, in short, is fetishized. And as is often the case in media, being fetishized is only a prelude to being violated:

Katayama is not literally raped — the other boys merely strip him of his clothes in public. But the imagery is clear enough — especially since Ito takes care to draw Katayama as doughy and shapeless. If you looked at these pages out of context, it wouldn’t be clear whether Katayama was supposed to be a boy or a girl. His humiliation and his appearance both emphasize his feminization; he becomes unmanned before he becomes unhuman. And, in fact, it’s precisely at this moment of violation that his transformation takes it’s next step, and he develops a spiral on his back. Over time the spiral turns into a tumescence; a kind of inverted pregnancy. And then, inevitably, we get to see even more of Katayama naked.

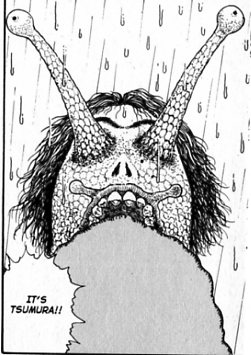

It’s at this point that the gender implications go from sort-of-subtle to hard-to-miss. Katayama’s parents are called to come take him home, but (in classic coming-out-scene mode) they refuse to recognize him as their son. The school decides to put the ever-less-human Katayama into a cage. The only sign of who he once was are those same giant lips (shown chomping away on some leaves)…and his relationship with Tsumura, the boy who stripped him in the quasi-rape earlier in the comic. Tsumura still loves to torment our ichorous hero, assiduously poking at him with a sharp stick through the holes in the cage fence while chortling, “He’s not human anymore!”

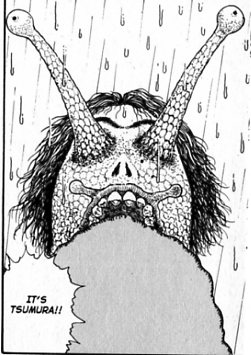

As it turns out, using a substitute phallus to toy with a giant snail has some unfortunate repercussions. Tsumura is soon drinking too much water and moving very slowly and then…well….

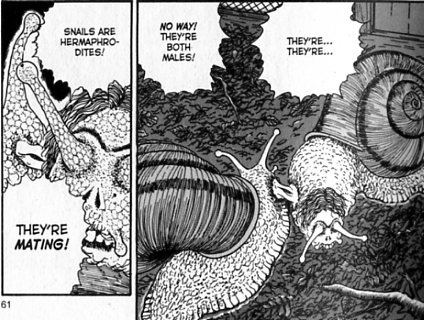

Tsumura is put in the cage with Katayama. The two get along quite well; in fact, they mate.

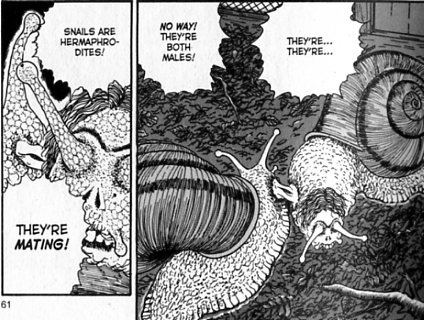

This is one of the most viscerally disturbing scenes in the book. In part it’s the details; leaving Tsumura his hair and teeth as the last vestiges of his humanity is a brilliantly vile move. Mostly, though, I think the scene’s power comes from the way it grabs homophobia with both hands and squeezes it till it oozes a slick, gelatinous mass. It’s not an original insight to point out the homoerotic implications of schoolboy antagonism, but there can’t be many fantasies of queer consummation that are quite this squickily perverse.

I said that this was a fantasy — and so it is. Ito obviously finds the snails and their male-male love disgusting…but at the same time, he also seems to feel a fascinated attraction. There’s a weird tenderness in the rapprochement between the two boy-snails, as they rest face to face with their phallic eyes intertwining.

In later chapters, this appeal turns significantly darker, as more people (always men or boys) turn into snails, and some townspeople (also always men) develop a decidedly sexual taste for (raw) snail flesh.

Ito seems to be suggesting that all men secretly want to — that the only thing preventing constant man-on-snail coupling are a few thin taboos which will warp and dissolve like cardboard before the smallest liquid spray of desire. This is, of course, the fever-dream behind the most alarmist kinds of homophobia; the terror, not so much that gays are recruiting, as that, with just a little prompting, men will embrace any excuse to abandon heterosexuality, and with it humanity. From a Freudian standpoint, you can see it as the combined fascination with and horror of the father; a desire for the power of the phallus which must be carefully regulated through totem and taboo if we are not to all slide into cannibalism and anarchy.

In this context, it is interesting that the final expression of horror at male reproduction is uttered, not by the girls who are the putative narrators, but by the teacher/father-figure, Mr. Yokota. After the two snails escape, the teacher and some students find a cache of eggs. Seeing them, Mr. Yokota declares that “the boys are no longer remotely human” — and his immediate impulse is to kill them and their offspring. The vision of unnatural male reproduction is too much to bear; the only healthy reaction to male-male affection is violence: Tsumura was right when he beat Kituyama, and wrong when he loved him. So, when confronted with the result of that love, Mr. Yokota does the correct thing: he shouts, “It’s disgusting, unnatural! These creatures mustn’t breed!” and he throws himself into an orgy of destruction — ultimately leaving himself exhausted and damp with a puddle on the ground in front of him.

The irony, of course, is that the snails don’t need eggs to breed. They only need loathing, or lust, or the fact that the two are indistinguishable. The final shock panel, shows Mr. Yokota turned into a snail-man, his body covered with what looks like damp eggs. There is no doubt that he deserves his fate; his snailing is clearly the karmic payback for his intolerance. But, at the same time, intolerance is what the father is there for; without arbitrary rules to keep us upright, we’d all be crawling on our bellies. Ito, like many horror creators, desires to fuck up the father even as he’s moralistically and hyperbolically nauseated by the implications. Id and superego circle each other, not-men crawling from the bellies of not-men in a slow and fecund spiral.