This review first appeared on tcj.com.

____________________

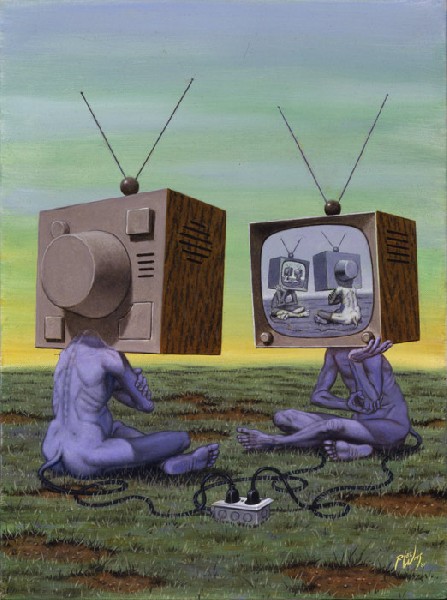

A lot of lowbrow art, from Robert Williams on down, leaves me cold. The slickness can be off-putting, and the kitschy cultural references get old fast. But really, the main problem is simply the glibness. The surreal juxtaposition of a crying whale and a television set with wings or whatever — it all seems like it’s been bunged together with about as much thought as I put into inventing that crying whale and that television set with wings. Advertising and garage sale art and outsider art all can be genuinely weird, but that’s because there’s an earnest animating spirit, whether utilitarian goal (sell Fruit Loops!) or genuine obsession. Lowbrow, though, seems motivated either by shallow irony or simple boredom.I mean, Robert Williams’ official site (http://www.robtwilliamsstudio.com/) currently features a painting of two blue humanoids with giant television sets for heads staring at each other — and on the television screen, there are two more television sets watching each other! And it’s called “Symbiotic Mediocrity.” Because, like, we’re all just watching one another watch one another in this brave new media landscape, you know? Deep, man.

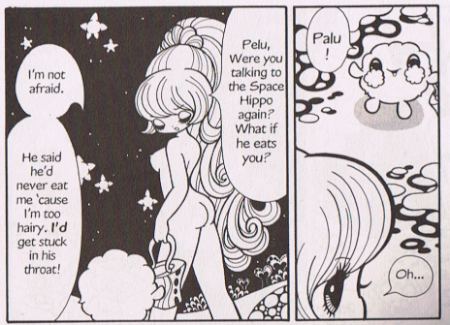

As is the way with lowbrow artists, Junko Mizuno is fascinated with cultural detritus: cute hippo figurines, saccharine cheesecake, adorable anthropoid fuzzballs. What separates Mizuno from her peers, though is (a) intelligence, and (b) genuine strangeness. As an example, Pelu, the main character in her most recent graphic novel, Fluffy Little Gigolo Pelu, is a small furry puffball; he lives on the planet Princess Kotobuki, which is populated by nude, human-appearing females. The women all have two little creatures like Pelu inside their bellies; when these females get old enough, the furry creatures inside them mate, producing a baby that falls from between the “human” females’ legs. Pelu’s host female, however, was eaten by a carnivorous space hippo before Pelu and his companion fuzzball could mate. Pelu was rescued from his host’s carcass by another woman, who raised him as her child. Eventually Pelu discovers who and what he is, and decides to go to earth to find a mate to replace the one he lost when he was an infant.

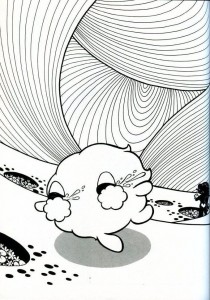

That narrative pretty much sums up Mizuno’s obsessions: sex, death, romance, kawaii, and the way they merge into a single melting rainbow of uncanniness. No wonder, then, that her artwork looks a little as if Aubrey Beardsley and Osama Tezuka got together to build a Barbie doll out of sugar cubes. One two-page spread toward the beginning of the volume, for example, shows several nude female silhouettes cuddling amorphous infant blobs against a sky of swirling patterns. In the foreground, Pelu runs weeping between pits of stylized flowers. The women with their babies look almost demonic in their maternal happiness, while Pelu’s tears squirt from his eyes in a manner which, given the nude girls in the background, rather queasily evokes other bodily fluids.

Like Williams’ blue staring televisions, the image here seems overdetermined. Unlike Williams’ image, though, the result isn’t didactic or smug. Instead, it feels queasily overripe, laden with too much meaning and emotion for comfort. Mizuno concentrates on surfaces not because they’re flat, but because of the infantile pleasure that lingers implicitly in every touch. Little Fluffy Gigolo Pelu is a story about a land not so different from ours, in which polymorphous perversion has crawled out of the nursery to swallow the world.