There’s a decent number of Wes Anderson spoofs floating around: his ostentatious and predictable style of filmmaking makes him a sitting duck for parody. However, most are only moderately successful– even SNL could only manage to blandly lampoon his work in “New Horror Trailer: The Midnight Coterie of Sinister Intruders,” a well-named skit which misses more targets than it hits. Why joke about Gwenyth Paltrow, who only appeared in The Royal Tenenbaums, when you could take on Jason Schwartzman, who has spent his entire career playing Anderson roles? Margot is iconic, but why not give the Anderson treatment to an existing horror icon? That’s the genius of the skit’s unaffiliated follow-up, “What if Wes Anderson made X-Men?,” which more than spiritually succeeds the SNL effort. It lovingly captures Anderson’s rhythms, charms, and awkwardness nearly beat for beat. On one hand, the Anderson-X-men pairing is so absurd that Patrick (H) Willems and his crew suggest that you could give the Anderson treatment to any series—What if Wes Anderson made The Flintstones? What if Wes Anderson made Breaking Bad? On the other hand, they make an amazing case for Anderson rebooting the X-Men in particular. Anderson’s quirky, nostalgic style would celebrate the goofy excitement and teenage longing of the original, while removing the toxic ‘epic-ness’ of recent reboots. In turn, the X-Men would give Anderson license to make the uncomplicated boys adventure story he clearly wants to make, free from intellectual expectations and his colonial pretenses. It’s a match made in heaven. Almost.

Wes Anderson would make an unexpectedly wonderful director of superhero movies for several reasons. First off, his films are devoted to the tension between boyhood fantasy, empty manhood, and maternal reason. (He makes a little room for feminine fantasy, which is often portrayed as wistful, and resigned to abandonment.) This axis resembles Superhero logic more than it departs from it. The superhero, a muscled Peter Pan, is the boyhood fantasy, and is juxtaposed to his faltering alter-ego who faces real life, ‘adult’ responsibilities. Superhero stories, however, tend to make dupes and conquests of the women. Not in the Anderson-verse, where the ladies call it like they see it, (even if their role is rather proscribed.) Wes Anderson’s third act typically calls for a reconciliation between fantasy and reality. He’s a generous filmmaker, in that neither side comes out victorious over the other; they instead consent to the necessary, life-affirming quality of both perspectives. I treasure Anderson’s formula, because I am grateful to find movies that simultaneously act as an ode, a critique, and an apology for grandiosity, and that don’t ignore the ways that women are often alienated by grandiosity. Thus, Anderson could honor the grandiosity of the superhero narrative, while assenting that this grandiosity can be destructive, delusional, and gendered.

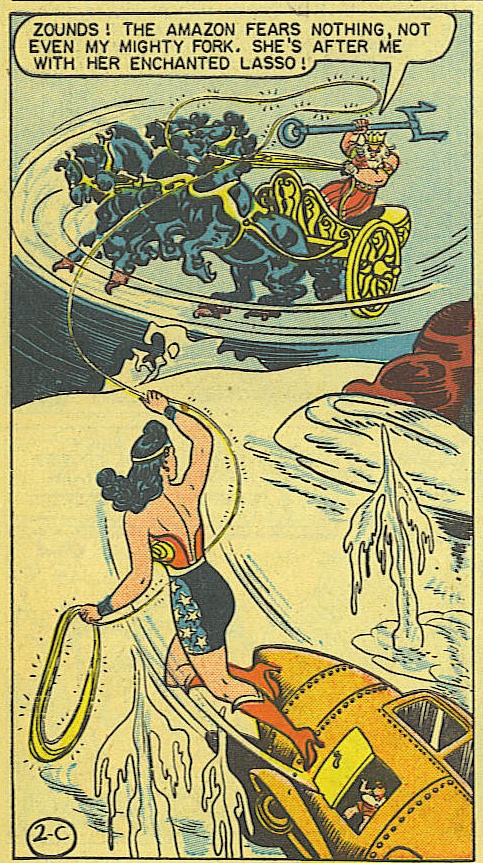

Secondly, Wes Anderson assumes that people go to the movies for the same reason they go to see a middle school play: to see someone they love say something amazing (and/or ridiculous,) while wearing an amazing (and/or ridiculous) costume. In essence, Anderson transforms celebrities into the audience’s family members. Fans will come to see who Bill Murray or Tilda Swinton will be in this one, or because they could never imagine Ralph Fiennes or Bruce Willis in that role, wearing those clothes. This isn’t so different from how comic books work– they are sold based on reader’s attachment to certain, iconic characters, who are put in unbelievable situation after unbelievable situation. Fan devotion is laid most bare in fan-art and fan-fiction, where fans put favorite characters, even destructive, “evil” ones, into absurd, adorable, and kinky situations. Wes Anderson’s style is a close relative of the fan-fiction mind-set. His films are ‘love letters,’ to Jaque Costeau, or the Austro-Hungarian empire, and his troupe of real-life actors. This may explain part of his appeal. Like a mother bird regurgitating food for her babies, Wes Anderson handles the digestion of a story beforehand, putting it on-screen so that its inherent love-ability is accessible to all, (who are willing to eat it.) Anderson would make a perfect match for superheroes, who are already celebrities and icons. He would derive great pleasure by putting characters into ridiculous costumes, in ridiculous settings and scenarios, while making them say earnestly ridiculous things. These components are already native to the genre, although most modern filmmakers try to evade or disguise them through ‘bad-assery’ and self-mockery. Wes Anderson would call a jump-suit a jump-suit, and would love every freaking minute of it.

Finally, the X-Men would be a wake-up call for the filmmaker. I have a sinking suspicion that each consecutive Anderson film reduces the female characters’ voices, reaching a point of near muteness in The Grand Budapest Hotel. As their voices fade, the films lose the friction that made his movies interesting in the first place, and the ‘boys adventure’ quotient increases inversely. Wes Anderson seems to be in the business of making bouncy, nostalgic escapades that lionize the value of cross-generational male friendship, and displaced father-son relationships. He’s careening head-first into superhero narratives, but he may be in denial about it, convinced that he’s actually making smart movies about the Austro-Hungarian Empire, (or Lord help him, fascism.) If Anderson were to truly commit to a superhero franchise, he might need to back-pedal a bit, and perhaps re-discover the power, and ethical necessity, of his earlier approach.

There’s a problem, however. Anderson’s style is inaccessibly white. His movies cater to white nostalgia about self-absorbed aristocrats. While I do not find him to be an explicitly racist director, I sometimes wonder why I don’t. He indulges in non-stop colonial nostalgia, from the wall-paper to the entire premise of The Darjeeling Limited. He employs racist language to elicit shocked guffaws from the audience, making his character ‘flawed’ in the way that your grandfather is ‘flawed,’—incorrigible, yet loveable anyway. But are they lovable? This friction makes his perennial father-son conflicts poignant, yet the racist language is never really addressed, or treated like a flaw worth resolving. Anderson cast an indeterminately ethnic actor as Zero in The Grand Budapest Hotel, playing a refuge from the Middle East, yet most of Zero’s lines are spoken in narration when he’s an older man– a role played by a white, Jewish actor. Anderson would white-wash perhaps the noblest part of the X-Men—its commitment to diversity, and its stories about civil rights, hate-crimes, prejudice, and genocide.

Then again, X-Men often does a pretty terrible job talking about racism. I am not an avid reader of the X-Men, and never have been, so I will cite the opinions of better informed writers than myself. In his piece “What if the X-Men Were Black,” published on this blog, Orion Martin comments, “What’s disturbing about the series is that is that all of these issues are played out by a cast of characters dominated by wealthy, straight, cisgender, Christian, able-bodied, white men. The X-Men are the victims of discrimination for their mutant identity, with little or no mention of the huge privileges they enjoy.” In “Mutant Readers, Reading Mutants,” Neil Shyminsky argues that the X-Men appropriates the Civil Rights struggles for a white audience, re-imagining these morality plays with white victims. He cites the work of recent authors like Grant Morrison in combatting this, but largely finds, “While its stated mission is to promote the acceptance of minorities of all kinds, X-Men has not only failed to adequately redress issues of inequality – it actually reinforces inequality.” Noah Berlatsky reviewed Jack Kirby and Stan Lee’s original X-Men, which was created before the series committed itself to having a diverse cast.

Noah and Neil both reflect that the original X-Men’s creators were Jewish men who anglicized their names, perhaps with the same mix of eagerness and frustration that Angel voices when trussing his wings behind his back. Most generously, the X-Men comics could be seen as a metaphor for Jewish assimilation and combatting anti-Semitism, but only of a masochistic kind: “[Lee and Kirby] nonetheless persevered in tightening that truss, which, in this comic at least, consisted not merely of new names, but of what can only be called a servile, deeply dishonorable acquiescence in hierarchical norms, casual misogyny, and imperialist fantasies.”

The films don’t look to be much better: Elvis Mitchell wrote of the 2000 original, “the parallels to the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (Xavier) and Malcolm X (Magneto) are made wincingly plain,” and “clumsy when it should be light on its feet, the movie takes itself even more seriously than the comic book and its fans do, which is a super heroic achievement.” You can’t accuse Mitchell of being a hater, however: he repeatedly extols the poignancy of the original comics in comparison, saying, “Perhaps that was the reason “X-Men” comics struggled and failed initially; the world wasn’t ready for misunderstood young martyrs with special powers saving the world and living through unrequited flushes of love.”

Wes Anderson would be the kind of director who would value those flushes of love, while completely disregarding the “seriousness” of the series, special effects, civil rights and all. The Anderson treatment would be honest about the X-men’s heart, but it would also be a confession of defeat. I’m not sure whether Patrick H Willems intended that as part of the commentary: in 2011 he mocked Hollywood whitewashing in “White Luke Cage,” without really pointing fingers at anyone, least of all Marvel. “What if Wes Anderson Made the X-Men?” is part of a series of auteuristic take-offs on superhero properties, which are as much love-letters as spoofs. Intended or not, the skit functions like a critique of Marvel, not of the X-Men or Wes Anderson. How perfect would it be for Hollywood’s whitest director to re-make Marvel’s most prominently diverse cast? So perfect. That’s the sad part.