Ah, the Kantian sublime stands a great craggy edifice, its very mention sends shudders through the soul. Well not so much…however, talking about Kant is always fraught. The very name “Kant” invokes the sublime as one tries to wrap one’s head around his prolific ideas. Thus, to discover relationships on the comic page from the mind of the great Kant, it seems like a good idea to break his ideas into panel-sized pieces.

Published in 1790, Kant’s Critique of Judgment proposes two aspects of the sublime, the numerical sublime and the dynamical sublime. His rigorous mind comes to these two forms from his discussion of aesthetics and they represent for him an attempt to grapple with the sublime. Even though the sublime experience happens in the body, technically the sublime is our experience of what we see, Kant offers a diagnosis of what might trigger an attack of the sublime. I defer to medical, psychological terms because the sublime is a disruptive force that disturbs the human mind and body. The sublime disturbs order, well-being, bienseance in the Enlightenment sense and represents a charged and potentially dangerous experience.

The feeling of the sublime is a feeling of displeasure that arises from the imagination’s inadequacy, in an aesthetic estimation of magnitude, for an estimation by reason, but it is at the same time also a pleasure, aroused by the fact this very judgment of the inadequacy, namely, that even the greatest power of sensibility is inadequate, is (itself) in harmony with rational ideas, insofar as striving toward them is still a law for us.

So for those thrill seekers who love to be disturbed, disrupted and knocked out of complacency by comics, the question is where is it and how can I get more of it. For those who like to gaze at the stars and contemplate the enormity of space, actually you are engaging in both of Kant’s sublimes simultaneously, the dynamical unbounded, immense and the numerical that tries to count the stars and is blown away by the impossibility of the task.

At present, I want to count stars if you will, or more properly consider the improbability and achievement of representation of the numerical sublime in comics.

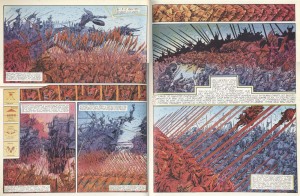

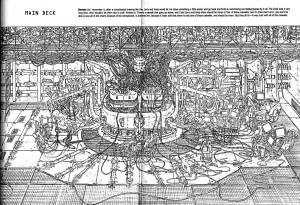

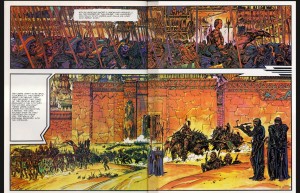

All that being said, it seems that there are self-evident reasons for artists not to want to draw crowd scenes, but there are some that thrive on the creation of minutiae. Phillipe Druillet for example undertook the task of representing Gustav Flaubert’s Salammbo and the results are stunning.

In this image, the ziggurat panels and small inserts of emblems, add order and assistance to a series of complex, visually stunning images that refuse easy assimilation.

Druillet orders the panels so that the densely articulated depictions of soldiers become patterns. The patterns take on aspects of movement as the viewer struggles to rest his focus on any single aspect of the dense and lushly colored planes. The panels allow us to fall into these impossibly detailed surfaces and while his gesture is conceivably an attempt to contain the sublime, we even add into the landscapes because we resolve the problem of the numerical sublime with an articulation of infinity.

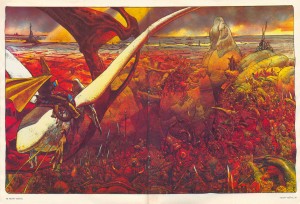

Moebius his contemporary, also works with scale and prolific figures. This overhead spread literally gives the reader a birds eye view of the sprawling action. The detail draws the viewer into the depth of the landscape.

Further, Moebius constructs space in such a way as to open geographies with limitless potentials. At the same time, his vision manages to bring a plausibility to bear that gives a substance to the fearsome scope of his world. This image has a life outside of the panels.

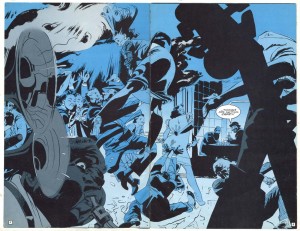

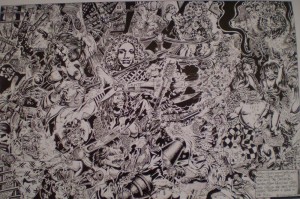

His influence is readily obvious in this piece by Geoff Darrow for film “The Matrix”. The narrative of the film suggests the numerical sublimity of alternate universes or of unleashed and uncontainable technology. Darrow’s image suggests an unnerving numerical sublime.

Darrow’s work is compelling in its detail. Yet, a strange thing occurred when I began to seek the numerical sublime depicted in comics, the examples that I thought I recalled, were not there. Apparently, my imagination had filled in the blanks. I was surprised to find that the imaginary capacity to see a more complex world in one’s imagination is not limited to words and reading, but it seems we are able to do this with visual data as well. We are able to store that imaginary information as though it we had seen it. I’m sure the experience of looking for an image that “one is sure is in the comic but just isn’t there when you look” is a commonly shared event.

I definitely thought there were more figures in this Frank Frazetta image for example, the movement and depth of field left me believing that I had seen more than was actually there.

As it turns out this is incredibly useful to the overworked artists who dread the hyper-multiple. Milton Caniff shares this story about how he dealt with the the demand for the impossible:

The writer comes in sits down, sits at a typewriter and types out this paragraph to direct the artist. The artist comes in and has to draw a man and a woman standing on a windswept hill and 10, 000 Chinese communists coming up with drawn bayonets. Now when you’re the artist and the writer you do the same scene, but you show a fairly close up shot of the hero and heroine, some wind lines and clouds behind with a few leaves going by to show a windswept hill. The man has his arm around the girl, pointing outside the panel saying: “ Look! Here come 10,000 Chinese.” That’s when you’re writing. and drawing. And that’s to make the point.

SABA: You’re making it easier for yourself, is what you’re doing, (laughter).

Caniff: And that’s an exaggeration of the point, that the artist can control it. If he wants to he can draw the 10,000 Chinese soldiers, but usually he finds a way out.

All the same, Caniff takes the challenge:

These roiling compositions are rare, but notwithstanding, their accomplishment stays with the viewer long after they have been seen. It is as if they gather exponentially from the details and the superfluity that they offer.

Artist Tony Salmons offered pithy comments from his perspective in an interview with James Romberger about an artist’s challenges when representing crowds :

Salmons notes three seemingly innocent words often seen in scripts, ‘a crowd gathers.’ Salmons says, ‘A writer scripts or merely plots this line down on paper and goes on to the next scene. I spend an entire day researching, casting, lighting and acting out that crowd. Is it an opium den? SF or Hong Kong? Texas? German beer garden? Rainbow room at 30 Rock? What kind of crowd? If I do it with total commitment the considerations can go way beyond this. And the writer’s contribution is 3 words, ‘A crowd gathers.’ No matter what the story requires, the artist must make it so.

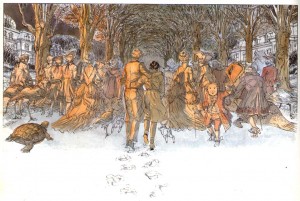

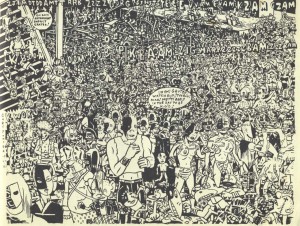

Salmons is clearly up to the task. His ability to work with space and depth, through black spotting and line work shows off his skill in this sublime image. Movement in the figures seems to amplify the effect in the depiction of a multiple figure composition.

James is also able to produce a crowd:

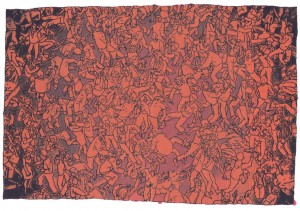

There are artists who it seems are born to create numerical chaos. James’ image was created during the LA riots in 1992. The numerical sublime seems to lend itself to revolutionary statements, both literally and figuratively. Consider how radically Gary Panter’s proliferating, unmoored marks assaulted the parameters of comics.

This type of chaos; of uncontained, irrational imagination stood in direct opposition to the world of corporate comics. Yet Panter was not the first to explore the possibility of overloading the senses to fracture the present from its traditional past. The sixties brought us S. Clay Wilson and other underground artists who filled the page with so many marks in the attempt to literally “blow our minds.”

It is hard to think of Captain Pissgums without his disturbing cohorts, or to image the revolting Ruby without her subversive dykes. Wilson, by the sheer volume of his outrages, insists on a dislocation from the anchors of America’s received concept of civilization in the sixties. More is always more. These images enter our brains and continue to propagate, because the sublime works to replicate itself. The sublime is sublime, it just keeps adding to its own being.

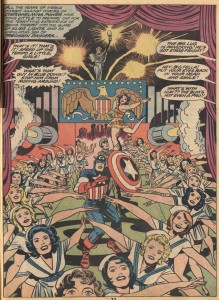

Jack Kirby too played with sex and the sublime, recognizing the sensory, even erotic power of its energy. For him in the image below, the sublime offers as a site of irony, perhaps bizarrely preemptively and philosophically connected to the vision of Wilson:

In Kirby’s vision, the senses demonstrated through a mania of eroticism, threatens the virility of Captain America and thus destabilizes the rationalist face of order to bring out a collapse of social coherence. While the gesture is not one that many feminists would at first relish, it is nonetheless interesting for its alignment of feminine energy with a romantic, revolutionary world. It is a world slipping out of control.

The numerical sublime is exciting and dangerous, precisely because it is uncontainable. It is hard to achieve, yet ultimately desirable as a destination for many comic artists who seek to escape the confines of the panel and the comic pamphlet. Bernie Krigstein discusses a project that he would like to undertake with John Benson in a special 1975 issue of Squa Tront and immediately falls into the abyss of the sublime as his concept multiplies itself into infinity:

BENSON: And you would adapt the entire novel?

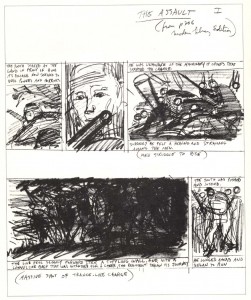

KRIGSTEIN: Yes; maybe hundreds of pages, or whatever the number of pages it would run to. But as I look at these sample breakdowns, even then I didn’t do it the way I would do it now. I still didn’t give enough space to the pictures. I would make it even much more pictorial in proportion to the number of words that it has here. I’d expand this passage here, where he’s running desperately; I’d expand it much more. And this one passage here, where the regiment is swinging from its position, could practically be a story in itself.

I’d have broader monumental breathtaking sweeping panoramas of the armies. I’d want to convey the notion of the enormity of it and then the contrast of the microscopic things going on inside of this enormity. And I would expand these sequences in order to elaborate on the microscopic things happening to where they’d have the character of deep stories. And the whole thing would be a connection of many many stories into one huge monumental panorama. These roughs still do not convey my real approach, what I would do right now. But some parts of it I find very satisfactory anyway.

BENSON: Actually, you’d have to excise some portions of the novel so that you could treat other portions fully the way you wanted to.

KRIGSTEIN: Exactly. But on the other hand, while cutting out stuff from one point of view, I would insist on an open-ended expansion from an editorial point of view. It might take 100 pages; or I’d like to have the freedom to take 1,000 pages for the same amount of text. I’d like to have no limit on the amount of space for pictures. But now I’m fantasizing; what I’m saying now is pure fantasy.

That would be a monumental enormous project. It means that every single one of these panels has to be a picture, a real picture, without compromising. I couldn’t rely that much on close-ups, either. I’d make it much more pictorial.

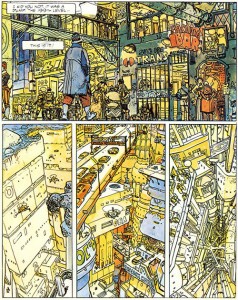

Krigstein never manages to enclose the scope of his discussion or one imagines, of his project. Its ability to continue to grow, exponentially and out of control is self evident in his comments and in his breakdowns for a proposed adaptation of Steven Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage. The depiction of these kinds of ideas present problems for the very best:

The lower left hand panel that represents the mass of troops has turned into an abyss of black marks. Chaos occupies the otherwise ordered mind and controlled hand of an experienced and competent artist.

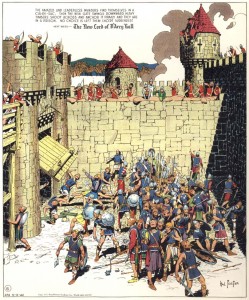

I leave with an image by Hal Foster, who often composed panels with multiple figures and I invite you to consider whether his images are ordered or chaotic. Whether and how the force of the numerical sublime can be made to serve its master, or whether it inevitably escapes free to roam unchecked.